Arthur Vööbus: Preserving A Legacy

Arthur Vööbus: Preserving a Legacy

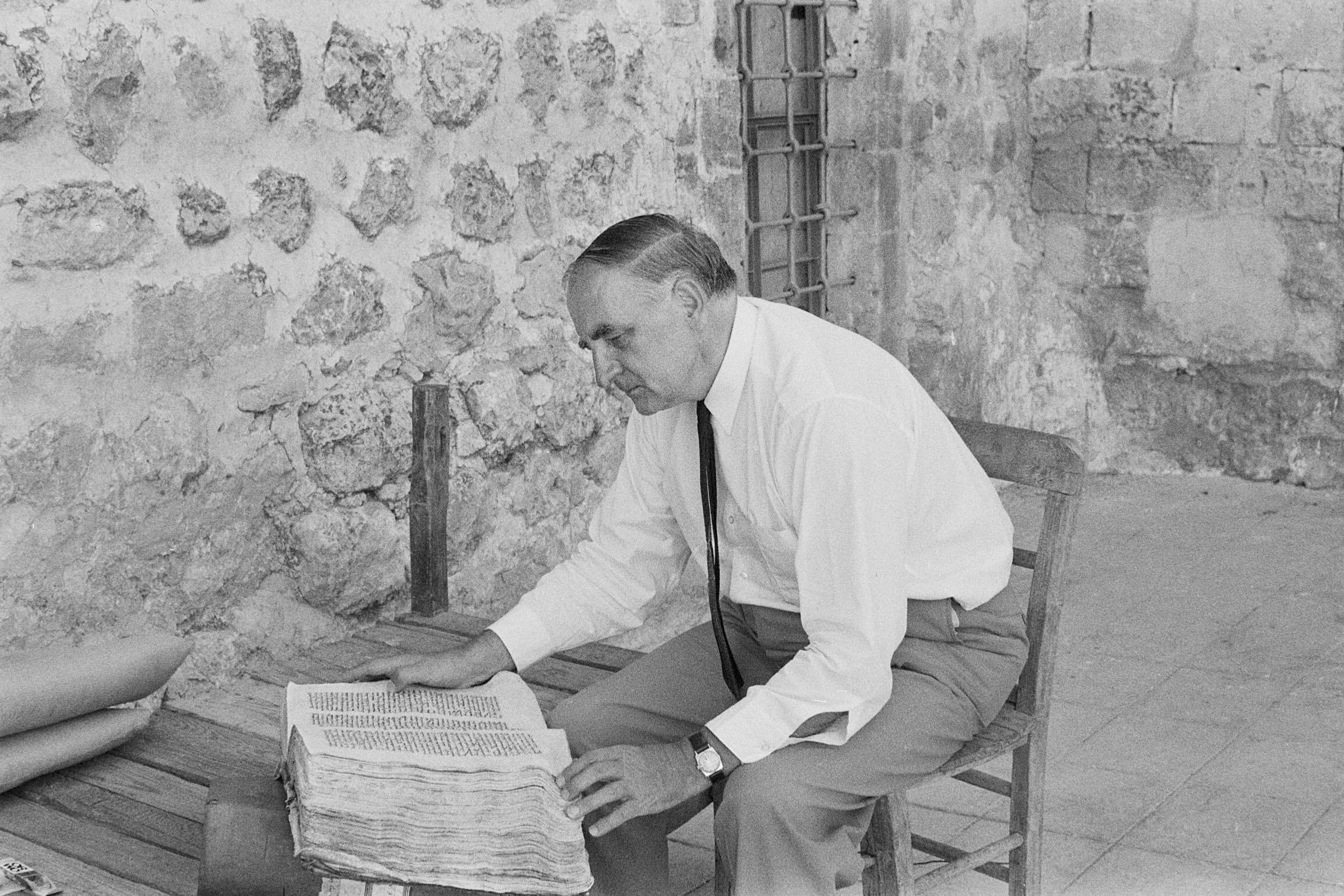

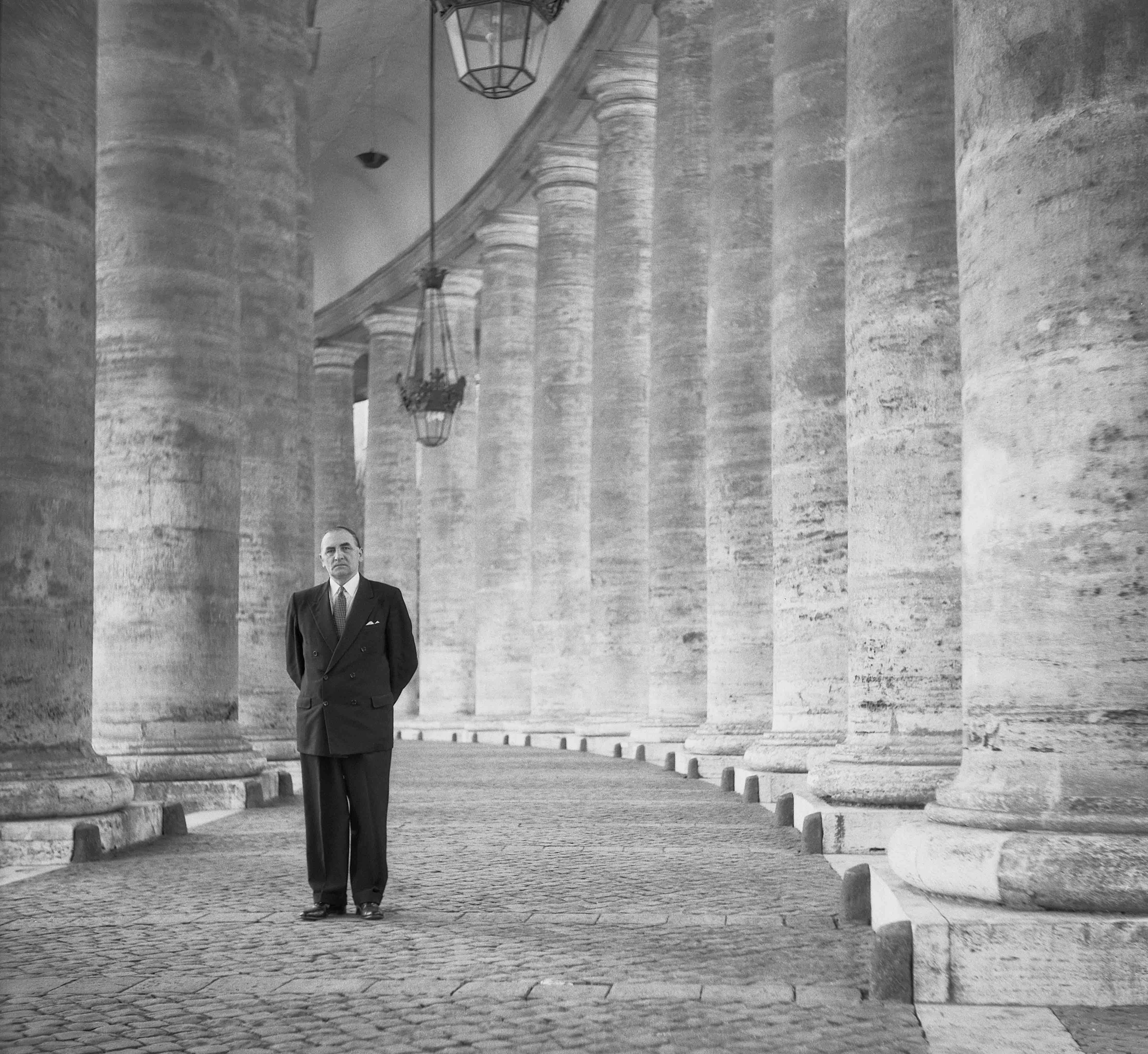

Dr. Arthur Vööbus was many things—a husband, father, scholar, pastor, teacher, and refugee in exile—but perhaps the best way to describe Vööbus is that he was a man on a mission, driven by his passion for knowledge and his compassion for his fellow humans.

Born in Estonia in 1909, Vööbus studied theology at Estonia’s University of Tartu in the early 1930s while also serving as a Lutheran pastor. The country would soon see three successive occupations by warring nations. In 1940, following the Soviet annexation of Estonia, Vööbus fled to Germany. He returned to Estonia (then occupied by Germany) in 1942, completed his doctoral degree, and began teaching at his alma mater. In 1944, Vööbus was again forced to flee from Soviet invasion. He lived in Hamburg, Germany, teaching at the Baltic University for displaced persons and serving as a minister in refugee camps. Vööbus relocated to Chicago, Illinois, in 1948, where he began a long career as a professor of New Testament and Early Church History at the Lutheran School of Theology at Chicago (LSTC). He died in 1988, having never returned to his beloved Estonia.

Syriac Manuscripts of the Middle East

Early in his career, Vööbus conducted research on manuscripts held in European collections and was introduced to Syriac literature. This serendipitous confluence created a lifelong curiosity about manuscripts that remained in the Middle East. In pursuit of Syriac manuscripts unknown to Western scholars, Vööbus made dozens of trips to Jerusalem, Lebanon, Syria, Iraq, and Turkey. Some destinations were based on common knowledge of manuscript repositories, while others were based on speculation. He was introduced to one important library—at the Church of the Forty Martyrs in Mardin, Turkey—by wandering around villages and asking strangers about manuscripts.

Vööbus’ motivation was deeply humanistic, rooted in his own education at Tartu and his conviction about education in public life. As Vööbus himself wrote, “The role of a learned man in a free society must lead to a deeper sense of the responsibility towards the society and the world.”

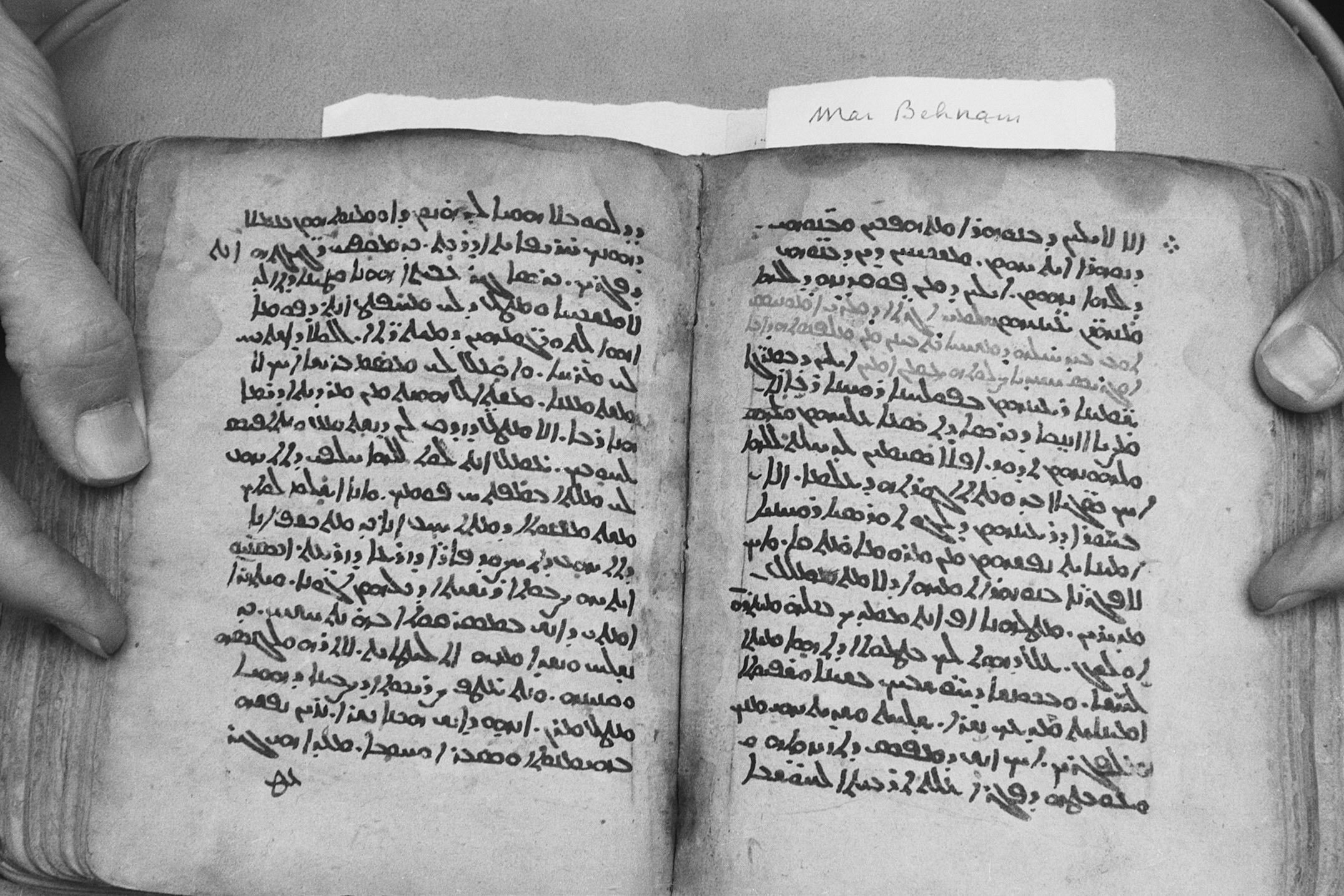

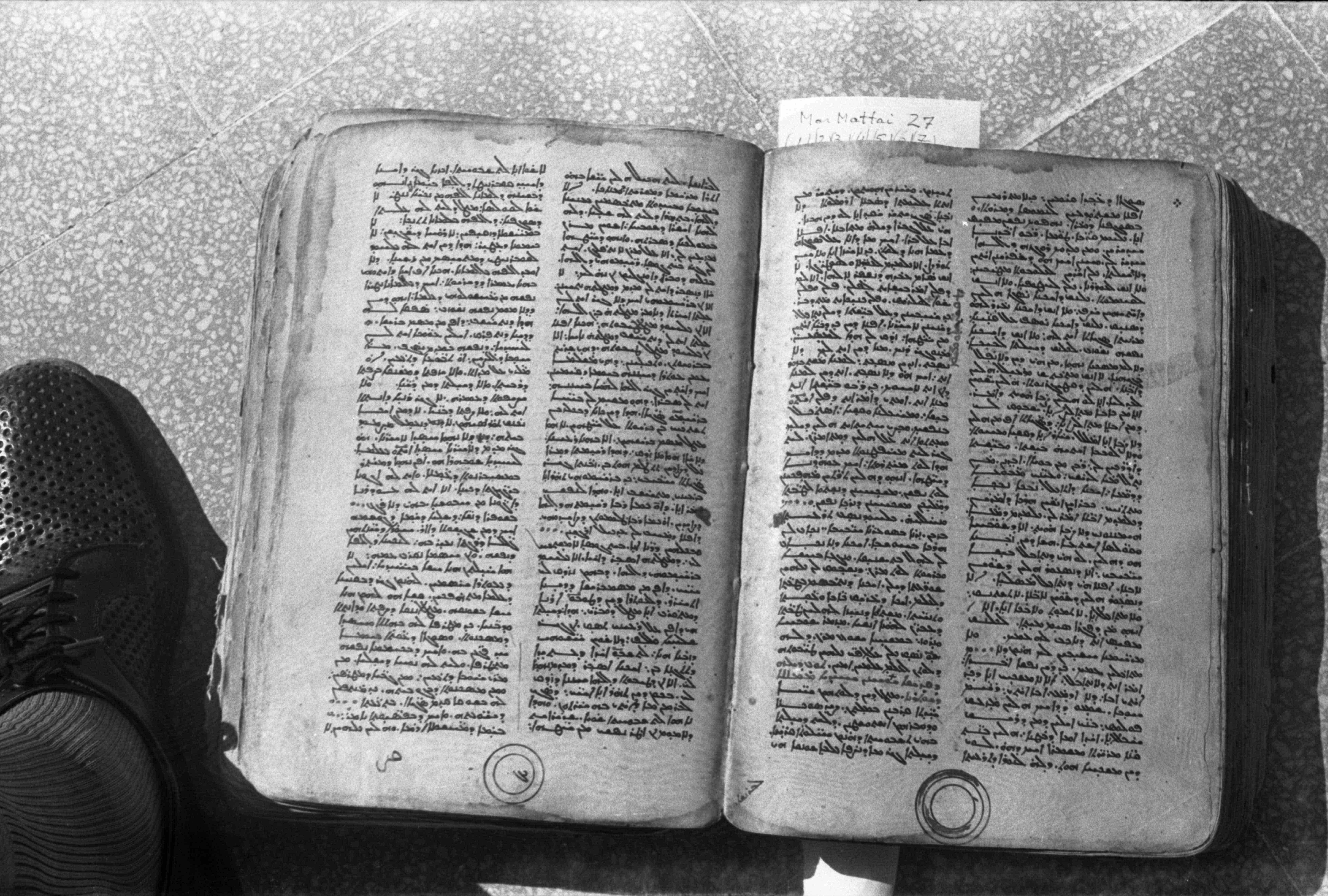

During his visits, Vööbus used a standard 35mm film camera to photograph his most significant finds. His collection of images grew to more than 65,000 photographs, many of which contain two pages of a manuscript. In the images, one can often see hands—either of Vööbus or a local assistant—holding the manuscript open. The lighting in the photographs is often inconsistent, suggesting that Vööbus was working with whatever daylight was available.

With these photographs, Vööbus created the largest collection of Syriac manuscript images before the advent of digital imaging. In some cases, Vööbus’ photographs might provide the only surviving vestiges of manuscripts that have been lost or destroyed. In other cases, these images provide access to texts from manuscripts that have been badly damaged.

In October 1979, Vööbus and his colleagues established the Institute of Syriac Manuscript Studies at LSTC, which became the new home for his collection of manuscript images. In 2005, LSTC entered into an agreement with the Oriental Institute at the University of Chicago, where Vööbus’ collection was partially digitized and cataloged. LSTC transferred full ownership of Vööbus’ collection to HMML in 2016, and the film was moved to HMML’s climate-controlled microfilm storage facility in Collegeville, Minnesota, for long-term preservation and access.

Advancing Research

Vööbus’ collection arrived at HMML in the form of hundreds of small film boxes containing loose film strips and reels. The boxes bore very little descriptive information about their contents—sometimes just the name of a city. In 2018, Mary Hoppe, digital projects assistant at HMML, began the laborious process of transferring the film strips to binder sleeves, entering the known data into a spreadsheet, and scanning each frame of film to produce digital copies. The work was slow and intermittent—balanced with other projects at HMML—until 2020, when the COVID-19 pandemic provided Hoppe with an opportunity to work on the project in earnest. Nearly all of Vööbus’ original film strips have now been digitized.

Digital images of the Vööbus Syriac Manuscript Collection can be viewed on a new website developed specifically for the project: HMMLVoobus.org. HMML’s usual method of cataloging individual manuscripts does not match the unique format of the collection, because Vööbus rarely photographed every page of a manuscript. Instead, HMMLVoobus.org presents the images as Vööbus made them, allowing his work to be viewed as a collection of historical film.

Vööbus’ original film strips, as well as microfilm images that he purchased, will continue to be stored at HMML. Coupled with digital access, this will ensure the preservation of a significant archive of manuscript photographs for generations to come.

A version of this story originally appeared in the Winter 2023 issue of HMML Magazine.