Where We’re Working: Ukraine

Where We’re Working: Ukraine

L’viv is a Ukrainian city whose multicultural past survives in at least two forms: its buildings and its books, particularly its manuscripts. A watershed between north and south, rain that falls in L’viv will flow eventually either north to the Baltic Sea, or south to the Black Sea. A gateway between west and east, L’viv lies in the province of Galicia, where the hills and forests of Central Europe begin to give way to plains that continue deep into Asia.

Metaphors of various kinds have been used to describe L’viv, depending on the point of view of the writers of its history. In the 13th century L’viv was seen as a bulwark of Christianity against a sea of Turks, Tatars and Mongols. In the 14th century it was described as an island of Catholics in a sea of Orthodoxy. Under Austrian administration in the 19th century, it was viewed as an outpost of cosmopolitan Poles amidst a vast countryside of Ukrainian peasants. For Jews in the 19th century, L’viv was the birthplace of their dream for a Jewish state, while Ukrainian intellectuals and Polish aristocrats made it the cradle of Ukrainian national identity during liberal Habsburg rule.

In 1988, L’viv was the birthplace of Ukraine’s move toward independence, and the place where the Ukrainian Catholic Church resurfaced after surviving for decades underground.

While L’viv has always had a small Ukrainian population, today it is nearly all Ukrainian. Large numbers of Ukrainians moved into the city from the countryside after Stalin, then Hitler, and then Stalin again deported or massacred its Polish and Jewish residents. Yet, L’viv’s architecture escaped Stalinist revision. From the ornate baroque and neo-classical houses with their sculptured balconies to its grand Viennese-style Opera House, L’viv’s architecture bears witness to the central European sensibilities of its vanished builders.

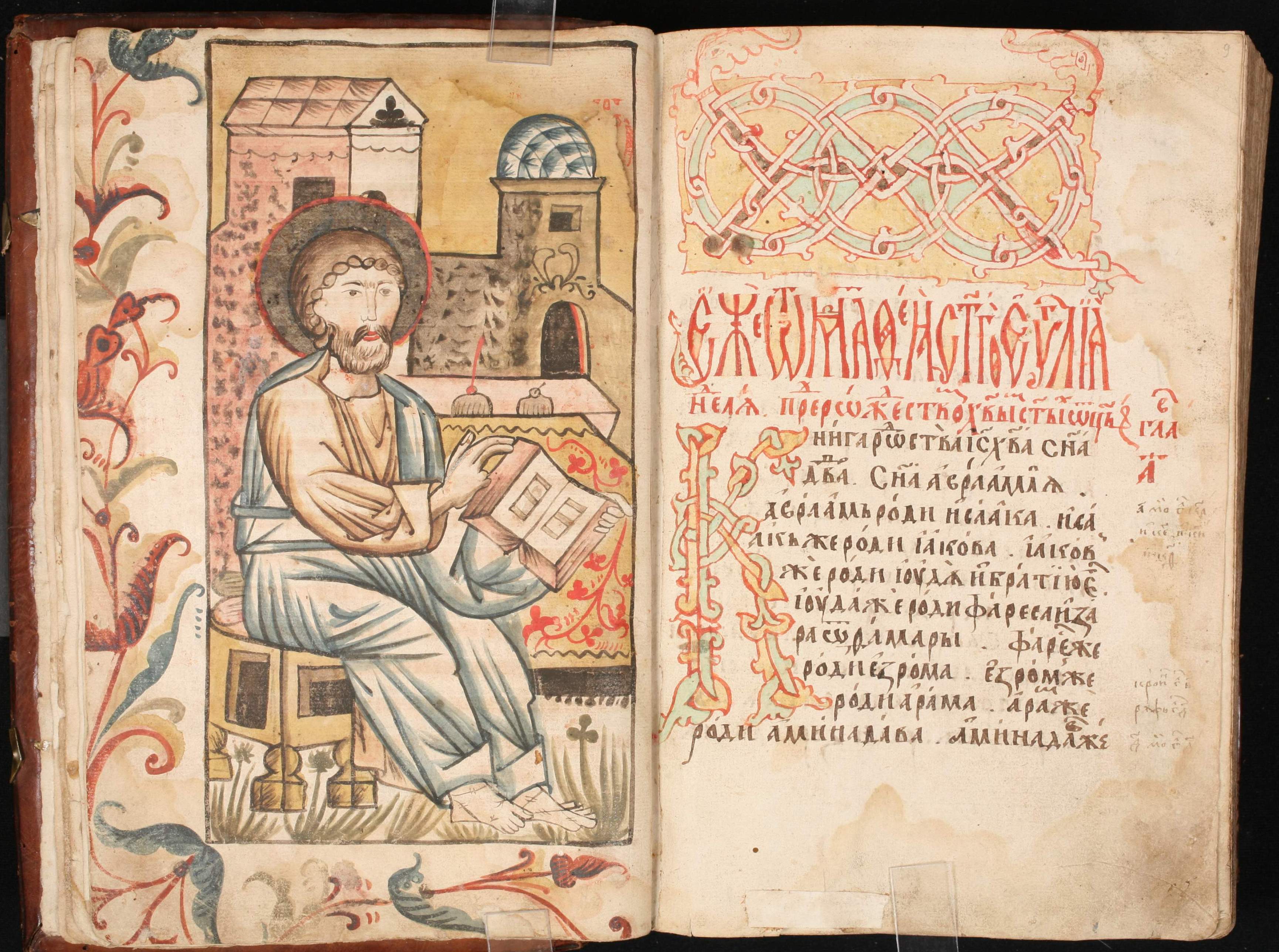

The evidence of L’viv’s multicultural past also lies recorded in the more than 5,000 manuscripts that can be found in L’viv’s state libraries. Collected from churches, monasteries, synagogues and estates from throughout Galicia, most of the manuscripts in L’viv are written in Latin, reflecting its Austrian and Polish Catholic identity, though many manuscripts are in Church Slavonic, reflecting its Ukrainian Orthodox and Ukrainian Catholic identities. Torah scrolls give evidence of its Jewish past, and Armenian and Turkish manuscripts reflect its location along one of the routes of the Silk Road. Indeed, after the horrors of the 20th century, the manuscripts in Lviv’s libraries are in many ways the most eloquent remnant of Galicia’s lost communities.

HMML is currently working with local partners to digitize the manuscript collections of the Stefanyk National Scientific Library, the second largest of Ukraine’s manuscript libraries, and those of the Lviv Historical Museum.

This story originally appeared in the Winter 2009 issue of HMML Magazine.