Women In The Courtroom: Legal Documents In Timbuktu

Women in the Courtroom: Legal Documents in Timbuktu

This story is part of an ongoing series of editorials in which HMML curators and catalogers examine how specific themes appear across HMML’s digital collections. From the Islamic collection, Dr. Ali Diakite and Dr. Paul Naylor share this story about Women.

Despite the vastness of Timbuktu’s digitized archives, it is, at first glance, a collection dominated by men. Texts authored by women are few and far between, and female copyists are rarely encountered (there are some examples; see our earlier editorial discussing female scribes).

However, there is one place where women are very much represented: in the courtroom—specifically in the large number of legal documents preserved across Timbuktu’s libraries.

Timbuktu has a long tradition of autonomous legal rulings, either made by the hereditary imams (religious and political leaders) of Timbukutu’s historical mosques or by local qadis (judges), legal experts who could be consulted by the city’s population on a range of issues. A judge’s work could involve issuing fatwás (non-binding legal opinions), made in reference to manuals of Islamic law on a certain topic requested of them. Fatwas did not necessarily involve named individuals, but they could inform other legal cases. Judges also handed down rulings (aḥkām), made in a court and in the presence of witnesses, which gave the name of the plaintiff or others involved in the case.

Legal documents show us that women had active roles as subjects and agents in such court proceedings. In this editorial, we will give you a sample of the kinds of life histories that Timbukutu’s legal records can illuminate.

Divorce

Prophet Muhammad said that “the most hated of the things acceptable to God is divorce” (Sunan Abī Dāwūd, Book 13, Ḥadīth 2178). In centuries past, as is perhaps the case now, divorce was the most complex legal issue that Timbuktu’s inhabitants might face. Though in Islam it is legal for both men and women to seek divorce from their partner, the case often has to be resolved before a judge.

The Timbuktu libraries include examples of women seeking to divorce their husbands both through khulʻa—in which the divorce is mutually accepted and the woman must return the marriage dower paid to her family by the husband as compensation (see ELIT ESS 02670)—and through faskh, where the husband does not agree to the divorce and it has to be mandated by a judge (see ELIT AQB 01301).

Other cases are more complex. ELIT AQB 00758 is a complaint brought by Alkālu bint Sīdi Muḥammad against her husband, whom she wishes to divorce due to his violence against her. The husband, for his part, asserts that she was mixing with other men, a statement the woman does not accept. The judge gives the opinions of many legal scholars, demonstrating that the woman’s case for divorce is legitimate if she feels physically endangered.

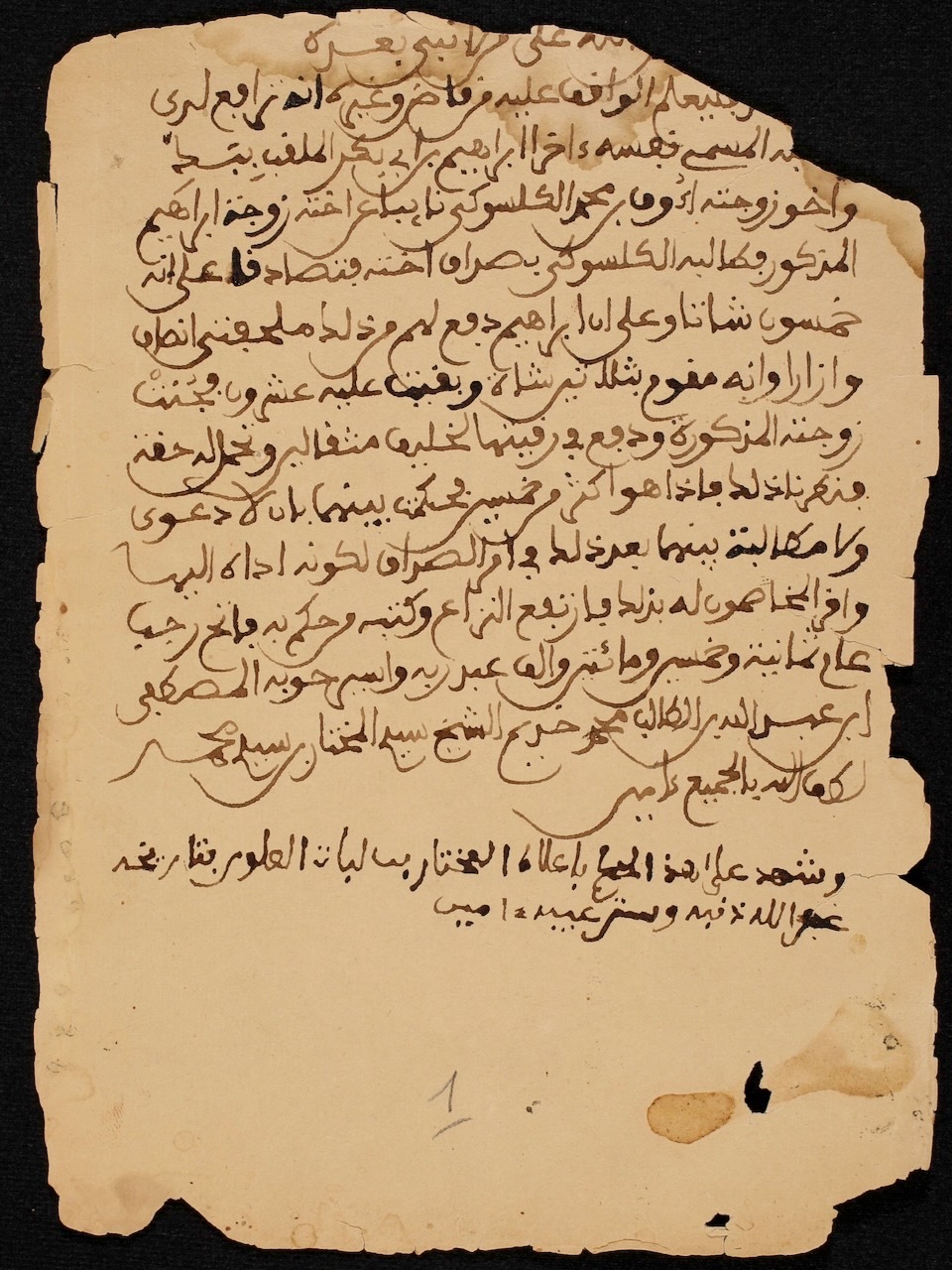

In SAV BMH 18957, ʻAwf ibn Muḥammad al-Kalasūqī represents his sister against her husband in a court case dating to August 1842 CE. The families had set a dower of 50 sheep, two rolls of fabric, and a garment for the marriage. Before the wedding, the prospective husband gave two rolls of fabric and 30 sheep, but his fiancé then became sick. He paid two mithqāl of gold—a unit of mass equal to 4.25 grams—to help her recover which, in addition to what he had already given, exceeded the dower. But when she was ready to marry, the family still demanded the remainder. The judge ruled that what the husband had already given was sufficient.

Inheritance

Inheritance is another matter often requiring the involvement of a judge. Several documents show that women played an active a role in these proceedings, representing themselves and their interests and dispensing with inheritance provisions as they saw fit.

Legal documents can offer us a window into the delicate negotiations and, sometimes, quarrels that arise after the death of a close relative and the division of their estate. ELIT WAN 00646 records that Halima bint Muḥammad and her brother divided the estate of their parents to their mutual satisfaction. SAV BMH 32608 is a notary document confirming that Amīnah used her inheritance to buy her father’s house from her co-inheritors, signed by two witnesses. ELIT AQB 01309 notes that Nana Moy used two mithqāls of gold, left to her by her father, to purchase from her brothers and sisters “a little, run-down house” that belonged to her father. The document states that the house “is now of her possession and she can do with it as she wills.” It was signed by Qaḍī Aḥmad Bāba ibn Abī al-ʻAbbās, who was a judge in Timbuktu in the early 20th century.

Another document, ELIT ESS 02873, demonstrates that some Timbuktu women amassed great fortunes in their lifetimes. The document announces the passing of Nana Ruqīyah in September 1883 and details how her estate was to be divided among her inheritors. Witness to the event were many Timbuktu notables, such as Qadi Alfā Muḥammad ibn Muḥammad ibn Muḥammad ibn ʻUthmān al-Kābarī, as well as the sons of San Shirfi, who was the imam of the Djinguereber Mosque until his death some 20 years earlier. Nana’s fortune included 84.5 mithqāls of gold, a house, and other items, to be divided among her five siblings and other named individuals.

These brief insights into the daily lives of women living in Timbuktu in the 19th to early 20th centuries show the value of studying the hundreds of legal documents preserved in HMML’s digitized West African collections. The collection can be found in HMML’s online Reading Room by setting the search parameters for Country: “Mali” and Genre/Form(s): “Legal documents.”