Contesting Saint Paul’s Shipwreck

Contesting Saint Paul’s Shipwreck

This story is part of an ongoing series of editorials in which HMML curators and catalogers examine how specific themes appear across HMML’s digital collections. On the theme of Weather, Dr. Daniel K. Gullo has this story from Malta collection.

The most famous weather event in Maltese history occurred in the first century CE, when a Mediterranean tempest sundered a ship carrying the Apostle Paul from Sidon, Lebanon, to Rome. Biblical scholars accepted the veracity of the storm and shipwreck as recorded in Acts of the Apostles (27–28). However, the shipwreck’s location was frequently contested, since the text of Acts contained some geographic ambiguity about where the storm occurred and where the apostle landed.

According to Acts, Paul’s ship broke apart during a storm while sailing in the Adriatic Sea—“navigantibus nobis in Adria” (Acts 27:27)—whence he subsequently landed on “Melite insula” (Acts 28:1). The question is, which of the Mediterranean islands named Melite did the apostle land on after the Adriatic tempest?

The long-standing debate reached a new crescendo during the 1730s when Ignjat Đurđević (1675–1737) contested that the Apostle Paul had landed on the island of “Melite Illyrica” (modern Mljet, in the Adriatic off the coast of Croatia), rather than on the island of “Melite Africana” (modern Malta, in the central Mediterranean). Mljet was located in Đurđević’s home country, the Republic of Ragusa. Previously, Đurđević had studied in Rome, where he entered the Society of Jesus (the Jesuit Order). He left the Jesuits early in his life and returned home to enter the Benedictine Monastery of Saint Mary, on the island of Mljet, in 1705.

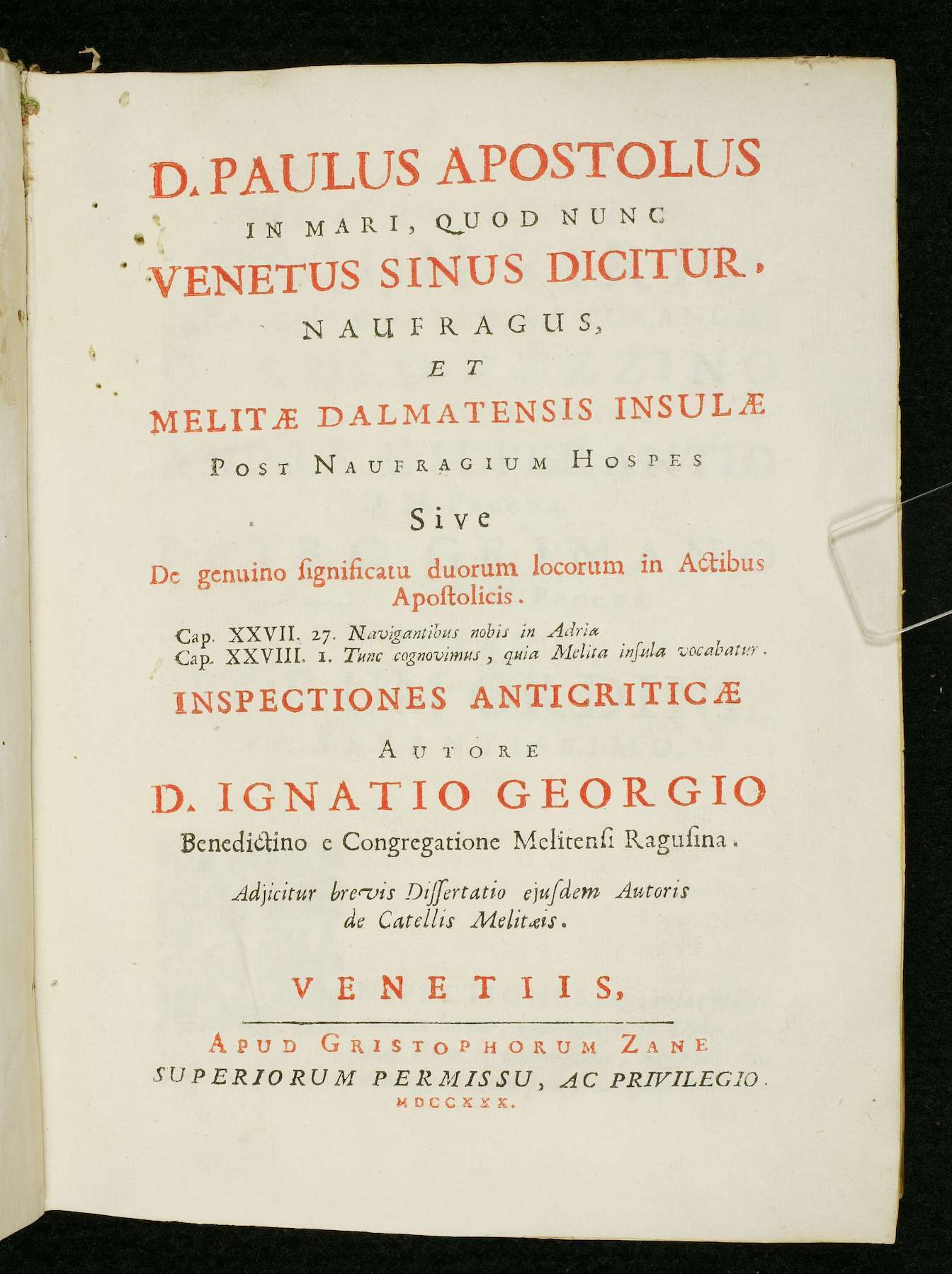

In 1730, Durđević’s island theory was published under the title D. Paulus Apostolus in Mari, Quod Nunc Venetus Sinus Dicitur, Naufragus, et Melitae Dalmatensis insulae post Naufragium Hospes (Paul the Apostle Shipwrecked in the Sea that is now Called the Blue Gulf, and Guest of the Dalmatian Island of Melite after the Shipwreck). This publication provided a systematic linguistic, historical, scientific, and cultural analysis arguing against any possibility that Paul could have landed in Malta.

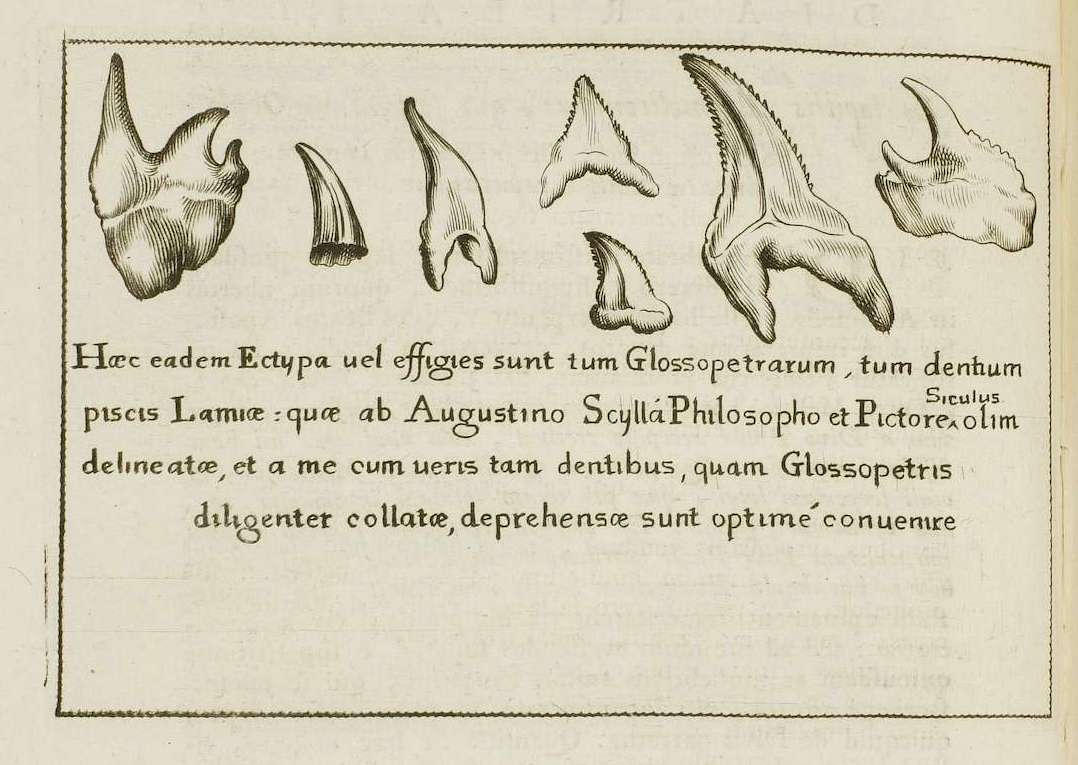

In the text, Durđević contends that the prevailing winds of the Mediterranean brought Paul further into the Adriatic during the storm. Durđević also attacks the cult of Saint Paul in Malta and its popular religious traditions, going so far as to debunk the relic known as the lingua Sancti Pauli and its curative functions—this popular tradition that held that fossilized sharks’ teeth found on Malta were in fact the “tongues” of the vipers vanquished by Paul after being bitten soon after arriving on the island.

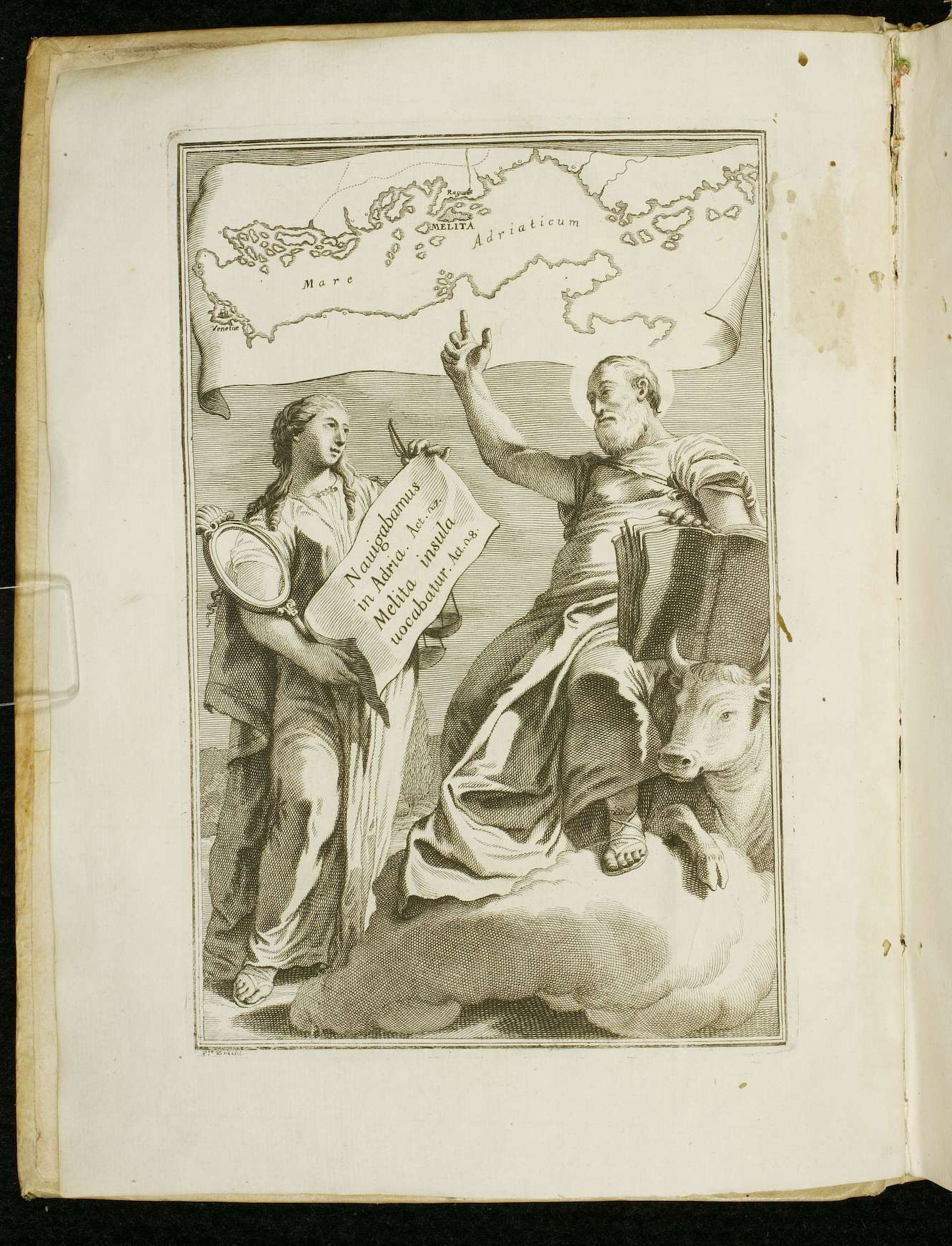

Đurđević commissioned the artist Giovanni Battista Tiepolo (1696–1770) to design an elaborate frontispiece that would visually validate his argument by evoking the authority of the New Testament. Tiepolo’s drawing, engraved by Francesco Zucchi (1692–1764), depicts the female allegorical figure of Truth facing the Evangelist Luke, who gestures directly to Mljet (“Melita”) in the Adriatic, rather than to Malta. Luke’s gesture supports Đurđević’s argument by aligning the passages from Acts with the island in the Republic of Ragusa.

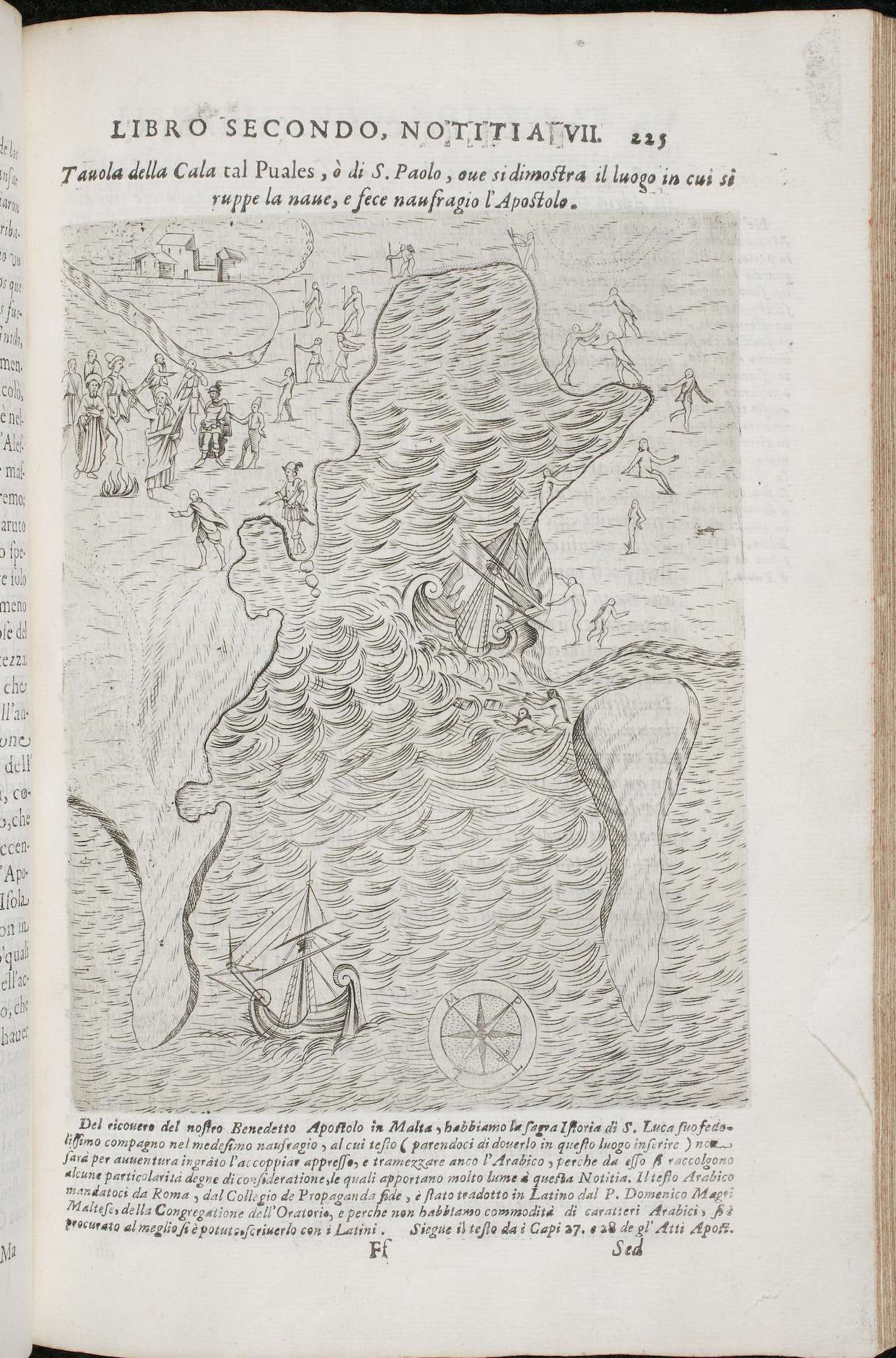

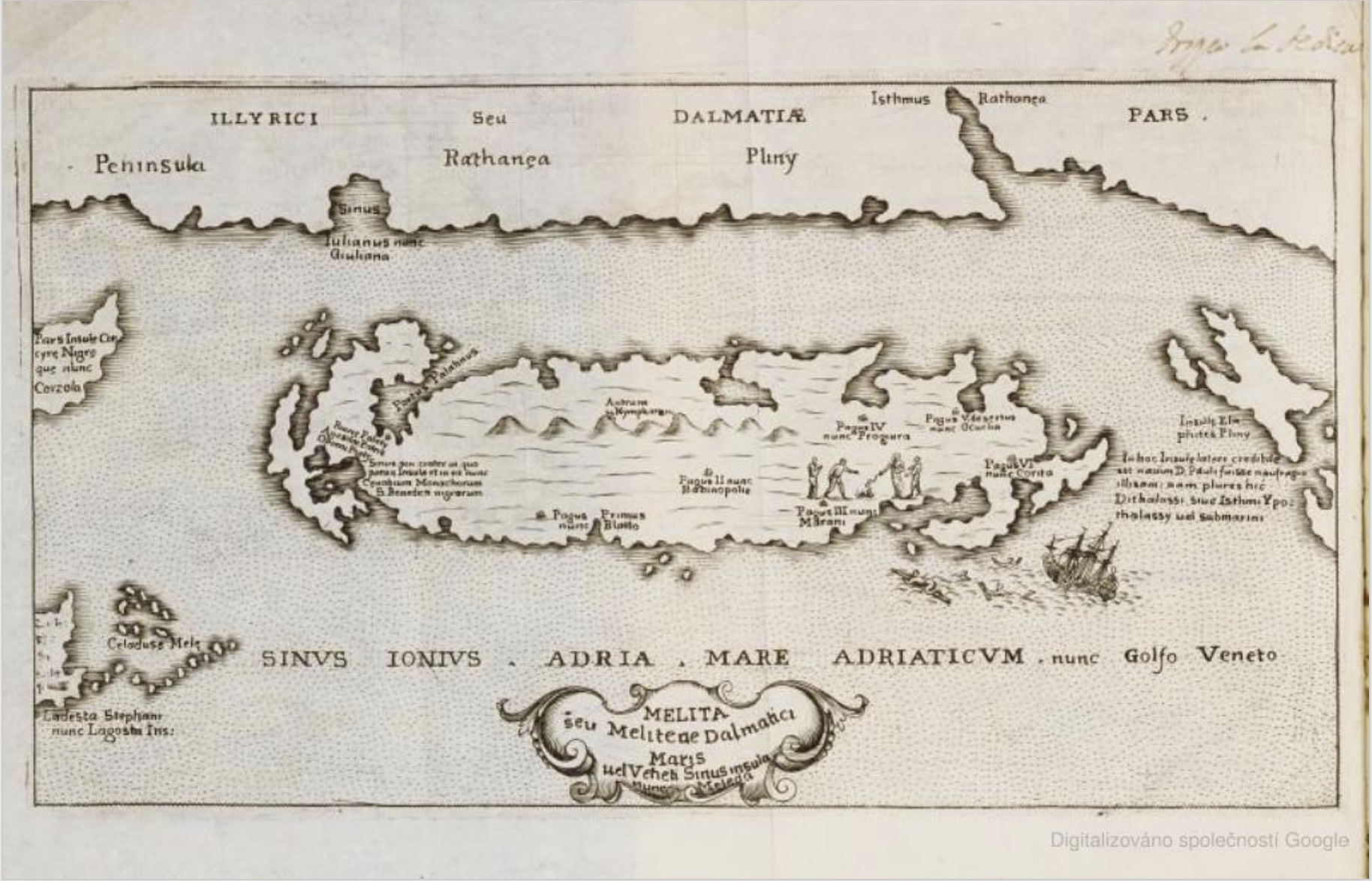

A second map in the book depicts Melite at the time of Paul’s shipwreck, including an illustration of the shipwreck and the subsequent miracle of the vipers that Paul performed after arriving on the island. Placenames and other features identify this island as Ragusa’s. The combination of classical geographic authority and biblical authority marshals two powerful forms of visual argument for the viewer. The engravings cleverly countered earlier cartographic representations that supported Malta as the actual island of Melite, such as the map found in Giovanni Abela’s Descrittione di Malta, printed in 1647.

Clarifying the location of Paul’s shipwreck was not a simple historic curiosity. Securing the exact location of the apostle’s landing had profound cultural, religious, and politic implications. Having an apostolic foundation not only granted authority to a nation, it also allowed locals to reap the benefits of pilgrimage to the holy sites historically linked to the first followers of Jesus.

Durđević believed in his research and wanted to encourage pilgrimage to the island where his abbey stood at the local center of religious life. He also wanted to raise the religious and political profile of the Republic of Ragusa as a Christian nation on the border of the Ottoman Empire. But Durđević’s thesis, if accepted, would come at a cost to Malta, which historically had been identified as the site where the apostle landed after shipwreck. Malta, too, was a small maritime power in perpetual conflict with the Ottoman Empire and its allies. Revived maritime activity in Ragusa coincided with the 18th-century maritime expansion of Malta under the Order of Saint John as a sovereign principality.

The historical and theological question posed by Durđević pitted the two small Christian maritime powers against each other for pride and place in the history of the early Christian Church. The interest in the Paul’s fateful storm and shipwreck thus can be seen as a proxy debate over Catholic maritime power in the region, as well as a traditional theological debate arising from new historical methods, science, and the appeal of cartography applied to biblical sources.