Travelers And Texts Crossing The Sahara

Travelers and Texts Crossing the Sahara

This story is part of an ongoing series of editorials in which HMML curators and catalogers examine how specific themes appear across HMML’s digital collections. From the Islamic collection, Dr. Ali Diakite and Dr. Paul Naylor share a story about Travel.

Mobility was a central feature of individuals, societies, and texts within Muslim West Africa’s educational networks. In this story, we look at a student, a pilgrim, and text journeying across the West African landscape and beyond.

A Student

As now, traveling long distances in pursuit of knowledge was often part of the student life. And teachers who specialized in teaching a particular subject of the Islamic curriculum, or even a particular text, would be sought out by students sometimes hundreds of miles away.

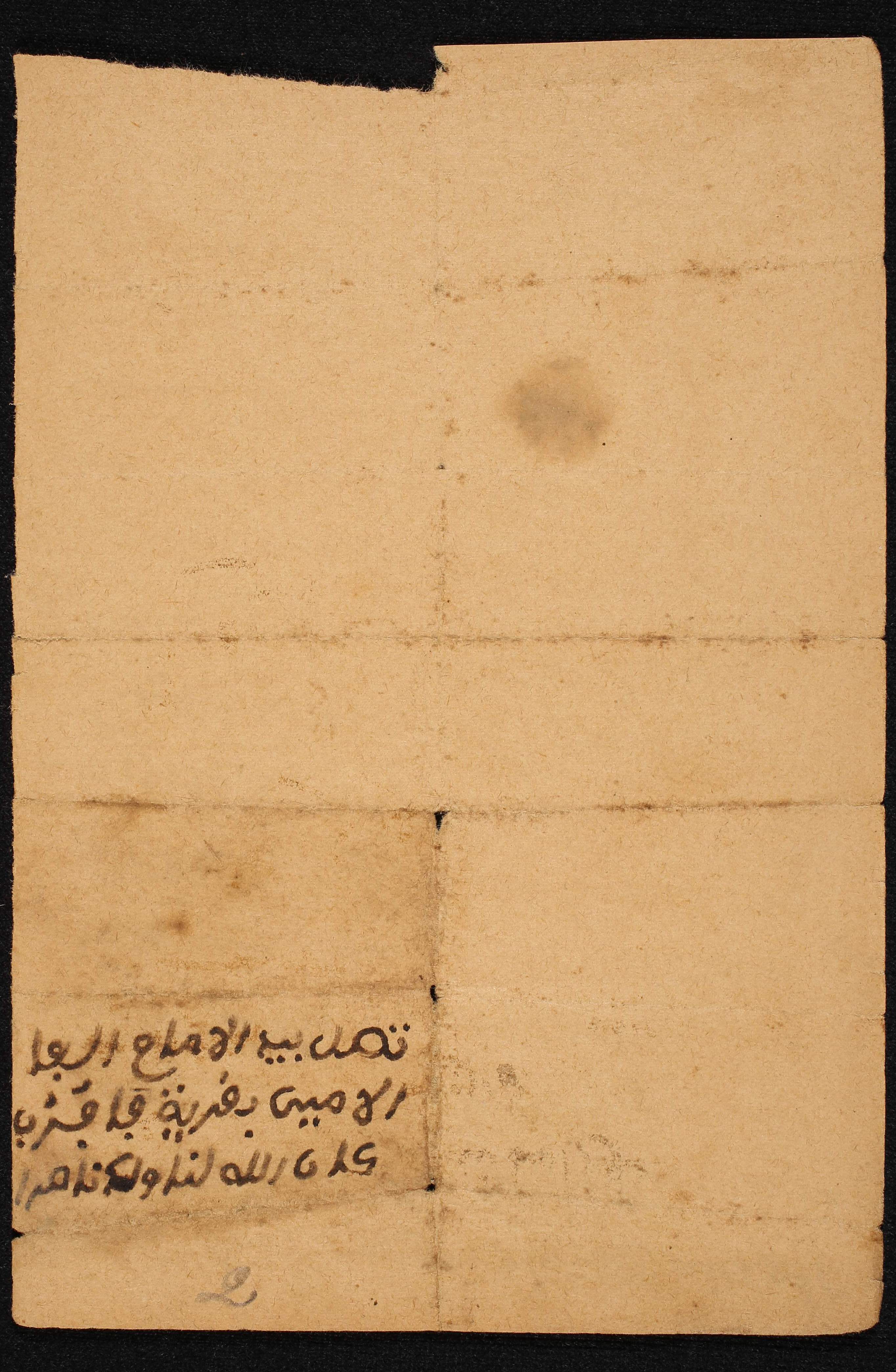

The student Ibn Sulaymān Tinbu wrote of his journey in a letter (SAV ABS 03015) to his father, Imam al-Amīn Tinbu. The son was evidently sent from his village, Fafurub, to another village for his education, but in the letter explains that he left because the teacher assigned to him “was unable to teach due to his ignorance of pedagogy.” Instead, he traveled to the house of Alfa Sīdī Tira, in another village, who he heard was a better teacher.

In the letter, Ibn Sulaymān asks his family to send him the six riyāls they had been saving up to buy a farm animal, so that he could instead buy the book Tanbīh al-anām (A prayer on Prophet Muhammad, of which two copies exist in HMML Reading Room). He writes that he would not be able to return before the end of spring, probably because he had to help his new hosts with the spring harvests. Ibn Sulaymān’s letter demonstrates both the complexities of finding a good teacher and the heavy physical and financial costs of obtaining an education.

A Pilgrim

Another reason for travel was the Haj pilgrimage to Mecca, enjoined upon all able-bodied Muslims. Performing the pilgrimage carried immense social prestige and was also an opportunity to develop spiritual and political connections in the wider region. Indeed, pilgrims often spent decades on the road.

SAV ABS 01761 records the pilgrimage route of ʻUmar ibn Saʻīd al-Fūtī, one of the most important scholars and leaders in nineteenth-century West Africa. His followers would go on to conquer Māsina and propagate the Tijānīyah Sufi order over a wide region.

The text narrates Umar’s pilgrimage journey. From his father’s village of Halwar in Futa Toro (modern-day Senegal), Umar headed east to Māsina in the Mopti region of Mali, at that time ruled by Ahmad Lobbo. There, he waited for a traveling companion before traveling on to Hausaland (in Northern Nigeria) where he spent time in the company of Muhammad Bello, ruler of Sokoto, and married two women. He reached the Hijaz and circled the Kaaba in Mecca, performing all the rites of the Haj.

Afterwards, he went on to Medina, where he met Shaykh Muḥammmad al-Ghālī, the local representative of the Tijānīyah, and along with a group of fellow pilgrims traveled on to the Levant. While in the Levant, he apparently cured a local ruler of insanity before returning to the Hijaz, making his way through North Africa and, presumably, crossing the desert to reach Hausaland once again. From Hausaland, he retraced his steps to Māsina and took the road west through various villages (Fāfā, Sām, Sinsindī) and Segou, traveling on through the land of Kankan and Futa Djallon (in present-day Guinea). There, he lived in various places before visiting Touba (again, in Guinea) and then finally returning to his hometown of Halwar.

A Text

The greatest travelers in West Africa were perhaps the written texts themselves. Manuscripts were often acquired while away studying (as in our first example), on pilgrimage, or bought from Trans-Saharan traders.

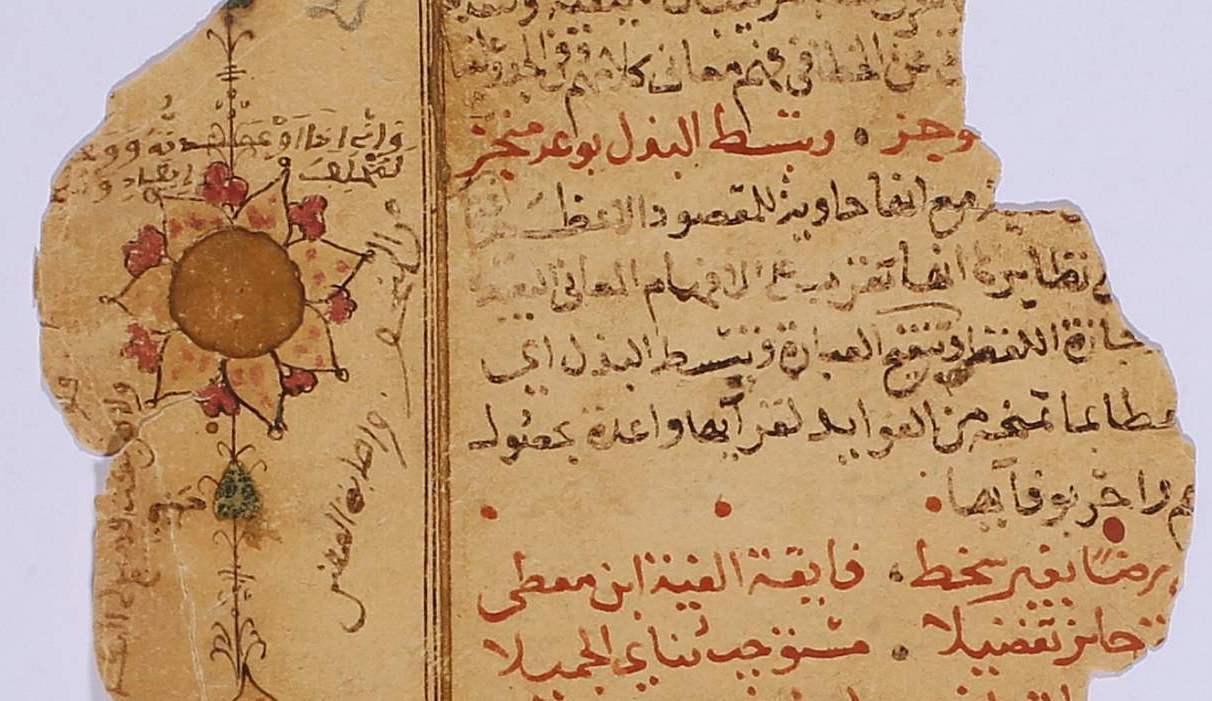

HMML’s digital collection contains photographs of manuscripts currently held by family libraries in Timbuktu, which we are in the process of cataloging at HMML. Several of the manuscripts in these family collections have clearly traveled far from the place where they were first written down. One of these is SAV ABS 00007, a commentary on Ibn Mālik’s Alfīyah on Arabic grammar.

The manuscript is written in the Naskh script, usually found much further east, and features floral designs in the margins of the first few pages. The textblock is deeply framed within a double red border, again uncommon in manuscripts of West African provenance. A note on page one lists several previous owners before stating that the text was acquired in February 1746 CE (Muḥarram 1159 AH) by the al-Arawānī family. Arawān, a settlement deep inside the Sahara desert, was an important entrepôt for caravans crossing the Sahara. It makes sense that this manuscript was brought there on camelback from the Middle East and was then purchased by a local scholar.

These three texts give us only a glimpse of the rich manuscript heritage of Timbuktu, digitally preserved by HMML’s work in the region. We will certainly come across more examples of travel as we continue to make more of this material available to the public.