Malta Envisioned By An English Clergyman

Malta Envisioned by an English Clergyman

This story is part of an ongoing series of editorials in which HMML curators and catalogers examine how specific themes appear across HMML’s digital collections. From the Malta collection, Dr. Catherine Walsh shares a story about Travel.

“...the entrance of the beautiful harbour of Valetta [sic]. Perfectly beautiful! […] The batteries down to the water’s edge, the array of shipping, the Saracenic effect of the buildings, and the spacious expanse of water entirely as it were within the town all is perfectly unique. The first appearance of the harbour on entering, is most imposing, as well as interesting.”

So begins the text of HMAR 00026, a compilation of Maltese travel sketches produced by the Reverend David Frederick Markham (1800–1853), an English clergyman who visited the island of Malta during the winter months of late 1845 and early 1846.

At the time, the island was ruled by the British government, which had taken control during the Napoleonic wars. It became a frequent travel destination for British citizens, particularly military men and diplomats for whom the bustling Mediterranean port city of Valletta was a stepping stone to the East. Markham’s perspective of the island, and his activities while there, highlight both the international nature of Malta and the ways in which European travelers presented an outsiders’ view of the local culture that they encountered.

This fascinating compilation, housed at the Malta Maritime Museum in Birgu, Malta, contains text and sketches by Markham, but the album, including the closing map of Malta, seems to have been assembled at a later date by an unknown hand. Markham’s text is presented as excerpts, but the source is unknown; perhaps preliminary notes were added to the album by a later owner or by one of Markham’s acquaintances or descendants.

Artist, antiquarian, clergyman, traveler

An amateur artist, antiquarian, and genealogist, David Markham was an Oxford-educated Anglican, who served as rector of Great Horkesley, Essex, and canon of St. George’s Chapel, Windsor. He was part of a well-connected and cosmopolitan family. His grandfather had been Bishop of Chester, Archbishop of York, and preceptor to the Prince of Wales and the Duke of York; his father was private secretary to Lord Warren Hastings when he was governor of India; his brother John was a lieutenant in the Royal Navy; and his brothers Warren and Charles, both military men, died at the Cape of Good Hope and in Jamaica, respectively. David Markham was not the first of his family to board a ship to explore the reaches of the British empire.

His “delightful holiday” served many purposes. Markham traveled alongside his wife, Kate, their son, David, and their daughter, Selina, in part seeking the health benefits of a Mediterranean atmosphere for his wife and son, a common reason for northern travelers to seek milder southern climates in the 19th century.

In Malta, the Markham family lived at Dunsford’s, described by Thomas MacGill’s 1839 A Hand Book, or Guide, for Strangers Visiting Malta as one of “the best lodging houses.” There, Markham took drawing lessons from a person he refers to as “Signor Schrantz,” probably the painter Giovanni Schrantz (1794–1882). He and Selina learned Italian from the librarian Dr. Cesare Vassalo. The family participated heartily in Malta society and entertainments, meeting the families of the British governor, Sir Patrick Stuart; the Anglican Bishop of Gibraltar, George Tomlinson; and various naval officers stationed in Malta. Markham gave a lecture on “Phoenician antiquities” and assisted in services on Sundays while visiting the island. And of course, he toured and sketched many of the “highlights” of Malta, those mentioned repeatedly in contemporary guidebooks.

The Drawings

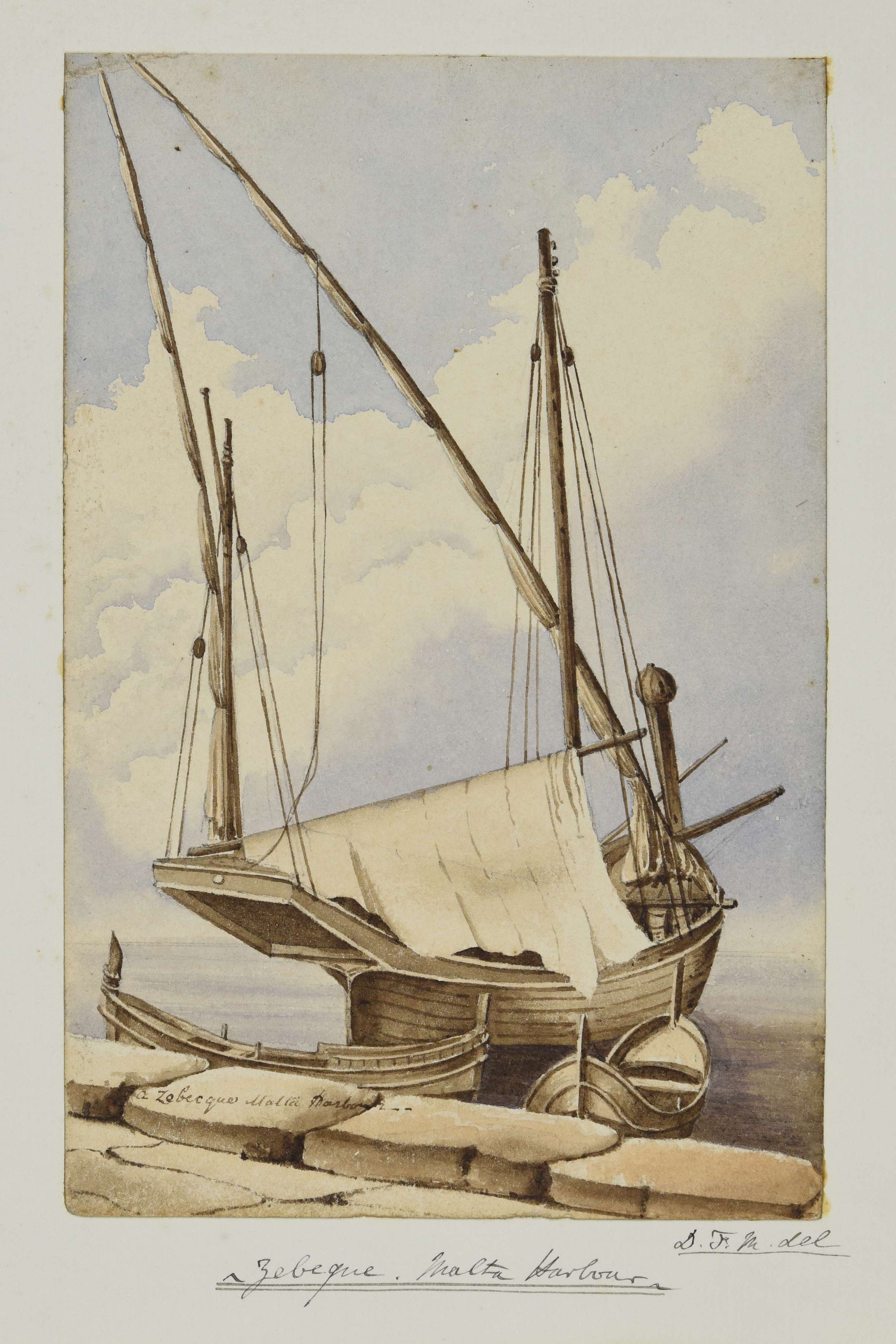

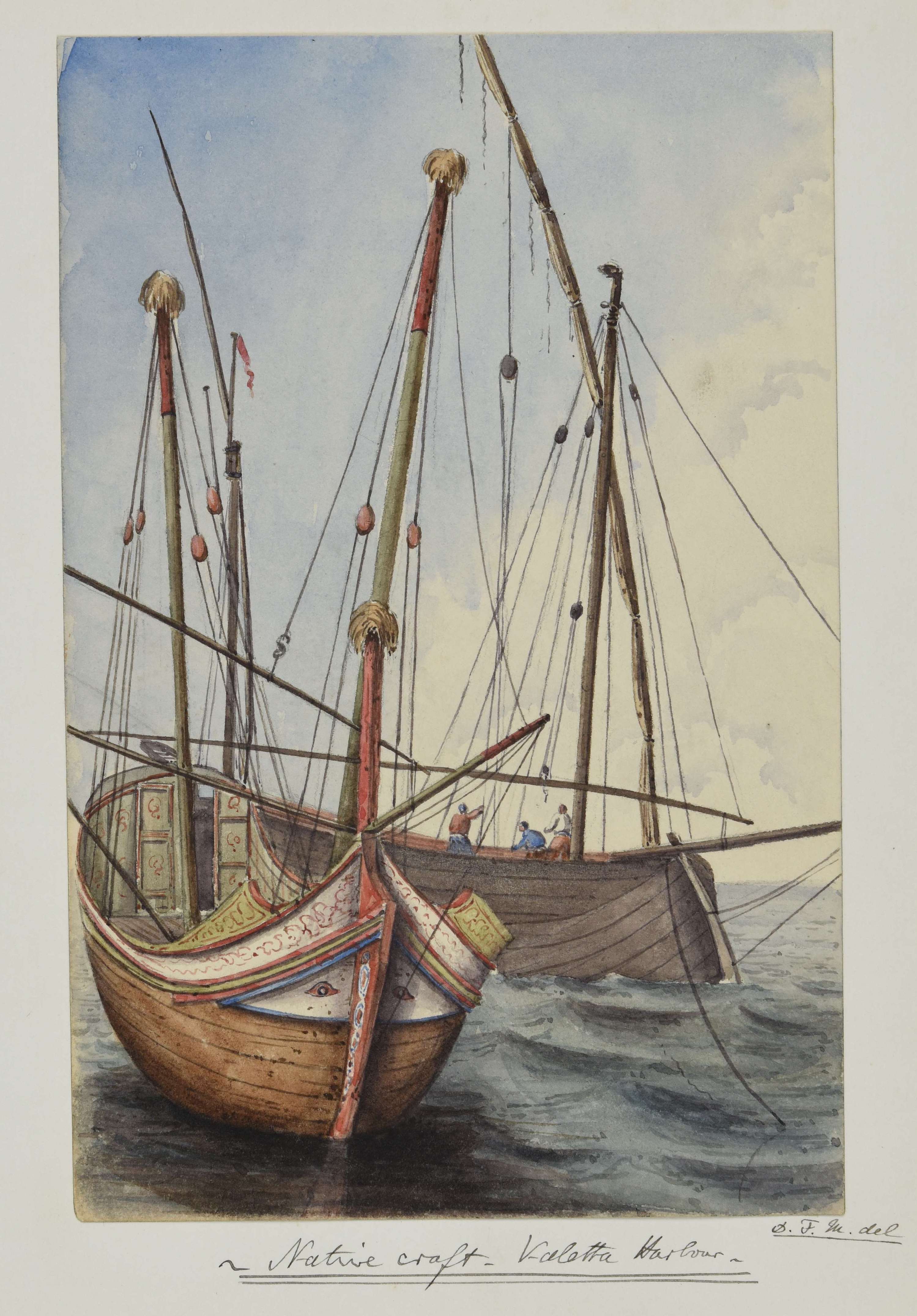

The highlights of the island included the harbor of Valletta, an elaborate and protective harbor famous for its international shipping and its defensive capabilities. Rather than presenting a landscape of the entirety of the harbor, Markham included two sketches of the unusual ships to be found therein. One is labeled by the artist as “a Zebeque Malta Harbour,” showcasing a local sailing craft frequently associated with corsairs (today usually spelled “xebec”). The second is described by the unknown compiler of the album as simply, “Native craft. Valetta Harbour,” and focuses on the curves and angles of the ship’s prow, picked out in blue, yellow, and red detailing with a painted geometric decoration to highlight the exoticism of the watercraft. This represents a speronara, another Mediterranean sailing ship.

Some of Markham’s images follow the tropes common in artists’ sketchbooks from the period and should be considered through the lens of imperialism—less as factual representations of how things were, and more as personal records of the artist’s own culture and opinions of the people and places he visited. For instance, the album includes sketches focusing on the exotic dress of local inhabitants, who are treated less as individuals and more as types. In “Costume — Valetta,” the loose clothes of hooded barefoot women are juxtaposed against an elaborately garbed fez-wearing Ottoman figure, a black-and-white-clad Dominican friar, and a brown-robed Franciscan monk.

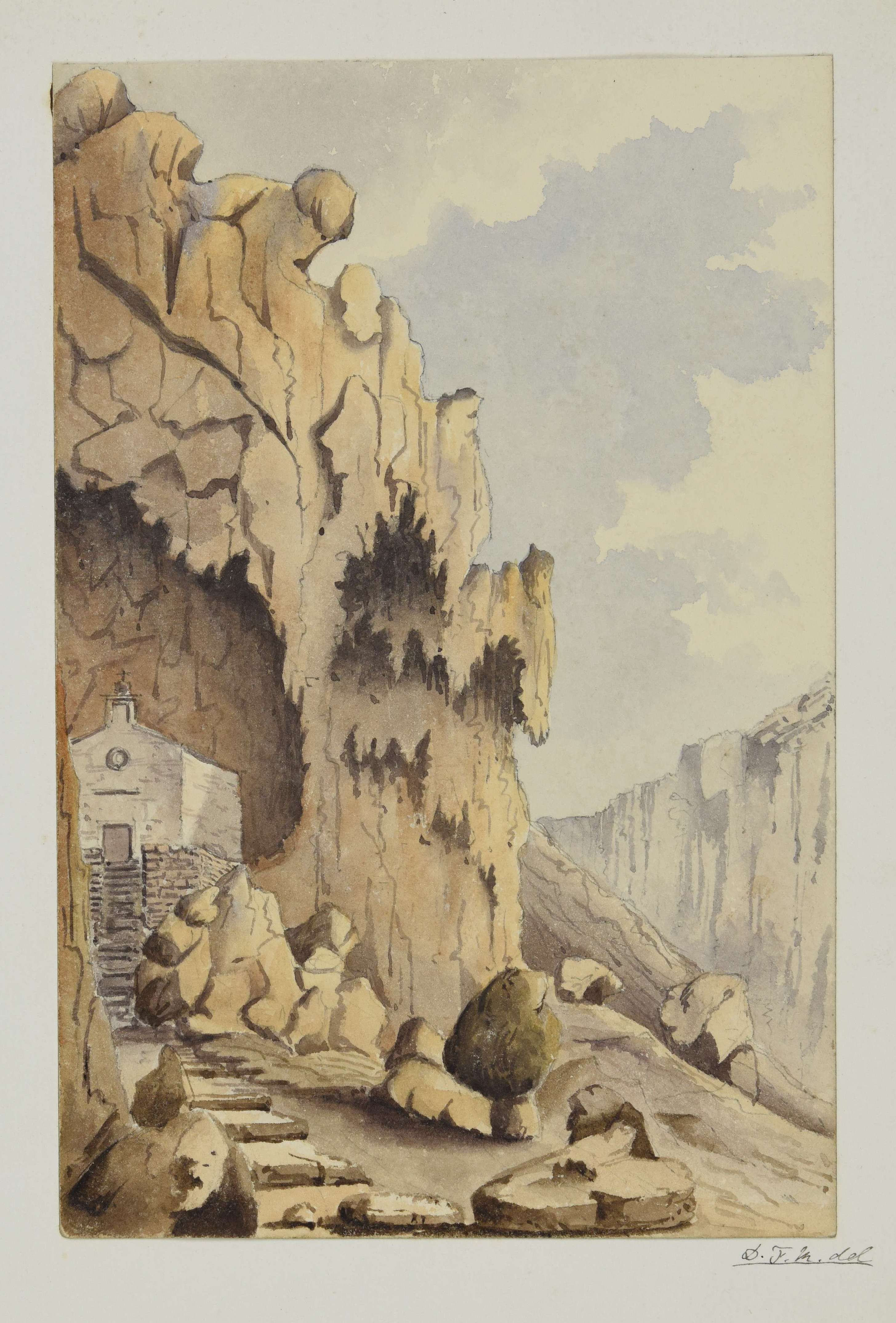

Other sketches contrast the environment of the rocky Maltese landscape with the cultural monuments that share the same terrain. One untitled drawing evocatively depicts a small, square church nestled among the alternately jagged and bulbous crags that engulf it.

Markham sketched the Pieta, the gardens of San Antonio, the Spinola Palace, the catacombs of the Città Vecchia, and other architectural and natural wonders throughout the islands of Malta and Gozo, many of them stalwarts of English guidebooks to the locale.

A trip to Hassan’s Cave (Għar Hasan) was lauded in guide literature. In 1838, George Percy Badger wrote of the attraction: “There exists a tradition among the natives, that this place took its name from a Saracen who resided in it for some time after the expulsion of his countrymen from Malta.” This politically-provocative and exotically-narrated site appears in both the framing text and in a sketch in HMAR 00026, but with only the most cursory reference to the story behind it:

“On the 22nd, there was a party to Hassan’s cave, at the back of the island, consisting of David Markham, his son and daughter, the Fogambes, Colonel Stuart, and Lieut. A. Phillimore R.N. It is a curious cave in the face of the cliff, and the approach is by a narrow ridge about 4 feet wide overhanging the sea, which is 300 feet below. It turned some of the party giddy, but Selina tripped along the path without hesitation, in her riding habit.”

In the pencil and ink sketch, “Gar Hassan — 200 ft above the sea,” the same perilous terrain described in the annotator’s commentary is dramatically pictured as a thin vertical sliver of land, clinging to the left-most edge of the picture, with Selina shown from the back as she ascends the path, mere inches from a drop into the water below.

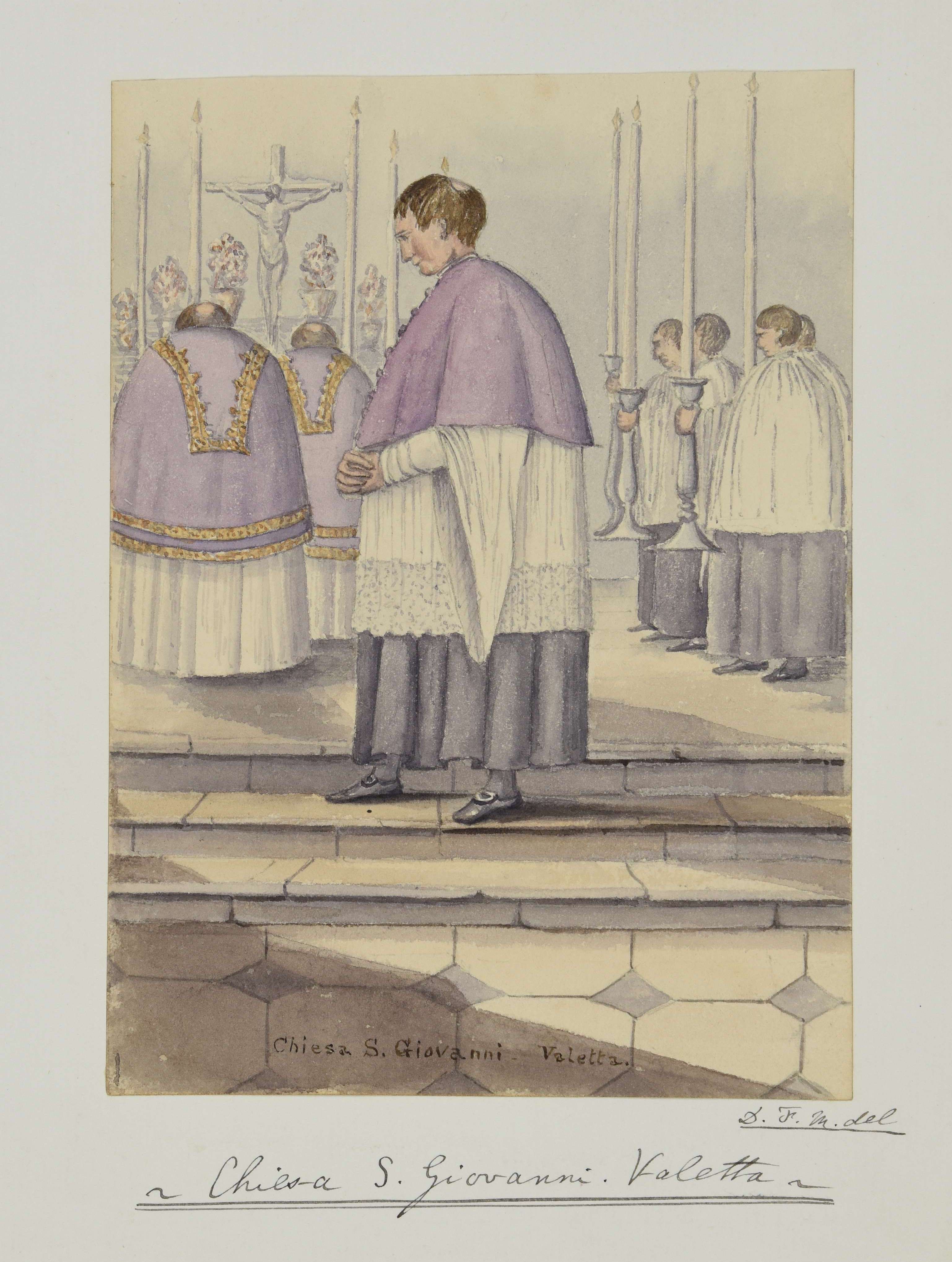

The sketchbook also includes less conventional drawings that hint at Markham’s attitude towards the places and people he met. As an Oxford-educated Anglican canon (Oxford University did not confer undergraduate degrees on Catholics until 1854), Markham likely would have had little experience with the Catholicism he encountered in the streets and churches of Malta. At a time when much Protestant-British travel literature either ignored or followed doctrinal lines to attack Catholic practices, Markham faced the topic head-on and without overt criticism.

His watercolor drawing, “Chiesa S. Giovanni — Valetta” depicts not the architecture, but rather the ceremonies of that church, where priests and celebrants in Catholic dress bow their heads in prayer before a crucifix. While the excerpted text of the journal lacks any mention of this imagery to tell us Markham’s thoughts on the subject, in his art he refrains from satirizing the scene beyond perhaps a tongue-in-cheek nod to the bell-like rotundity of the priests’ figures.

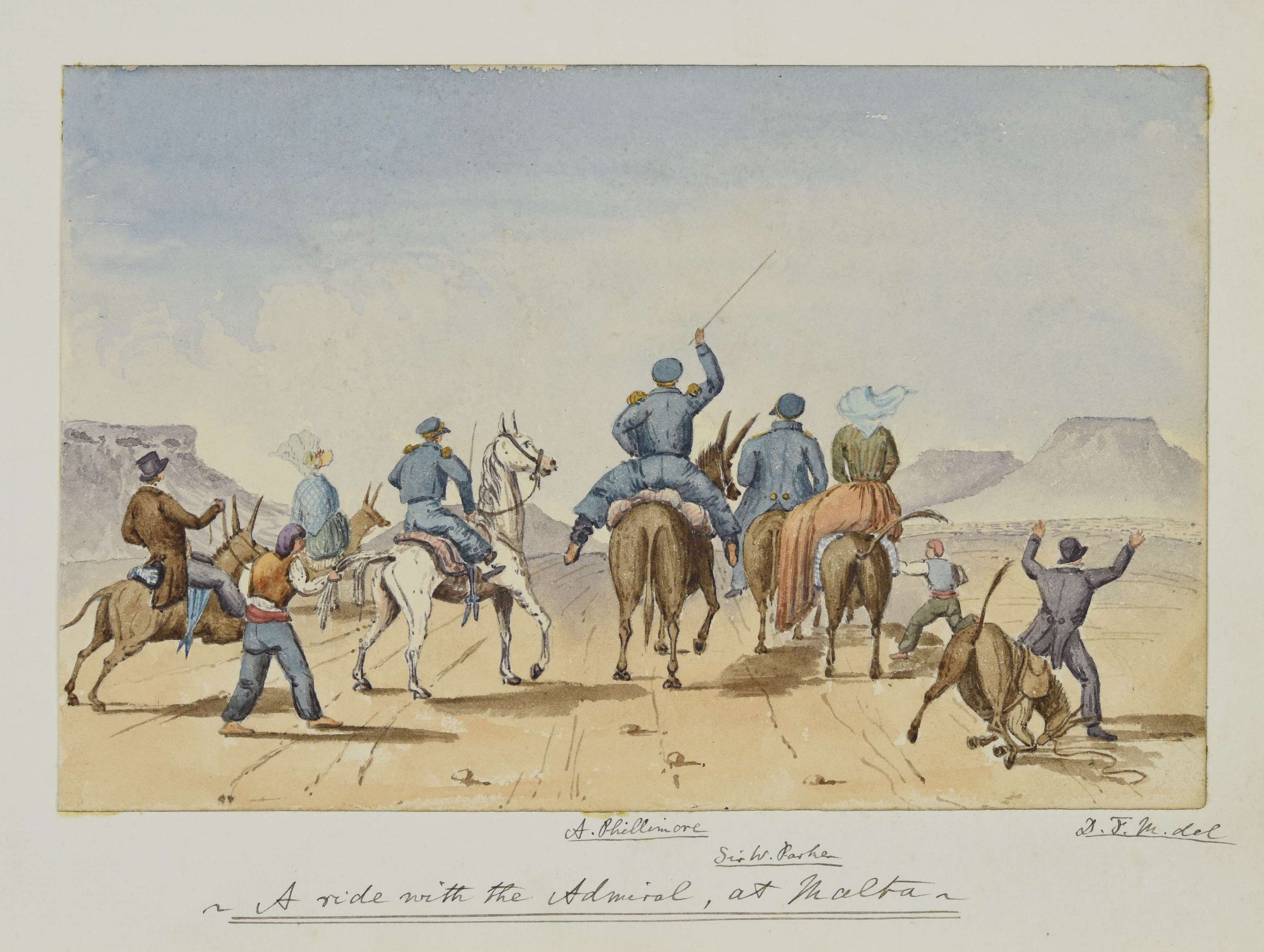

Instead, it is his British contemporaries who bear the brunt of Markham’s sense of the ridiculous. In his watercolor labeled by the album’s compiler “A ride with the Admiral, at Malta,” the artist suggests the chaos that can occur when dignified British subjects encounter the rigors of the Maltese landscape and the mules or donkeys commonly used to traverse its uneven ground. Though the image was likely never intended for public consumption, the artist’s willingness to laugh at his contemporaries—and himself—is marked.