Crossing The Red Sea In The 1640s

Crossing the Red Sea in the 1640s

This story is part of an ongoing series of editorials in which HMML curators and catalogers examine how specific themes appear across HMML’s digital collections. From the Western European collection, Dr. Josh Mugler shares a story about Travel.

In September 1647 CE, al-Ḥasan al-Ḥaymī left the port of al-Mukhā (Mocha) in Yemen and set sail on the Red Sea, arriving just two days later in Beilul, on the coast of what is now known as Eritrea. He would not see Yemen again for almost two years, and he wrote in a poem that the long journey “made my homeland dear to me because I have there neighbors with whom time is good, and they are good” (translations from Arabic by Emeri Johannes van Donzel).

Al-Ḥaymī was sent to Ethiopia by al-Mutawakkil ʻalá Allāh Ismāʻīl, imam of Yemen’s Zaydī Muslim community, on a diplomatic visit to its emperor Fasilides. Both Fasilides and al-Mutawakkil claimed descent from great prophets and rulers—Solomon and Muḥammad, respectively—and both saw themselves as heads of their Christian and Muslim religious communities. Al-Ḥaymī writes of his “contact with the king of the Christian sect and the Messianic religion, made at the order of our lord, the Commander of the Believers, the vicar of God who summons to His Clear Book.”

Both al-Mutawakkil and Fasilides were concerned about the extent of Ottoman power in the Red Sea and about Portuguese interventions in the Indian Ocean. Moreover, both oversaw times of relative power and prosperity. The Zaydīs had recently struck out from the Yemeni highlands to wrest control of the coastal plain from the Ottomans, prospering from the skyrocketing global demand for the coffee shipped from al-Mukhā. Meanwhile, Fasilides administered major infrastructure projects throughout his empire, including the castles and churches that filled his new capital city of Gondar.

In this context, Fasilides wrote in 1642 to al-Muʼayyad billāh Muḥammad, al-Mutawakkil’s older brother and predecessor, sending gifts and hinting at opportunities for greater intimacy between their kingdoms. As al-Muʼayyad and the two Ethiopian Muslim messengers wondered about the emperor’s insinuations, some suspected (and hoped) that Fasilides was interested in converting to Islam. The exchange continued for five years, Fasilides never explicitly stating his intentions, until al-Mutawakkil sent al-Ḥaymī to assess the situation in person.

At their hosts’ insistence, al-Ḥaymī and his party traveled through Beilul instead of the more established port of Massawa (modern Mits'iwa, Eritrea), then under Ottoman control. From their arrival on the African coast, it took six months to reach Gondar, beset by a variety of hazards. We can imagine al-Ḥaymī’s disappointment when he finally received a private audience with the emperor, only to learn that Fasilides had no interest in conversion, but instead wanted help to build up the Beilul route and thus evade Ottoman control of regional shipping. Al-Ḥaymī laments that “the king, I believe, was not completely acquainted with the conditions of this road…For if he had known them completely, I do not think he would have approved of it.” Suspecting that Fasilides had intentionally led them on, the embassy returned by way of Massawa. Some correspondence continued, but nothing became of the emperor’s plans regarding the port.

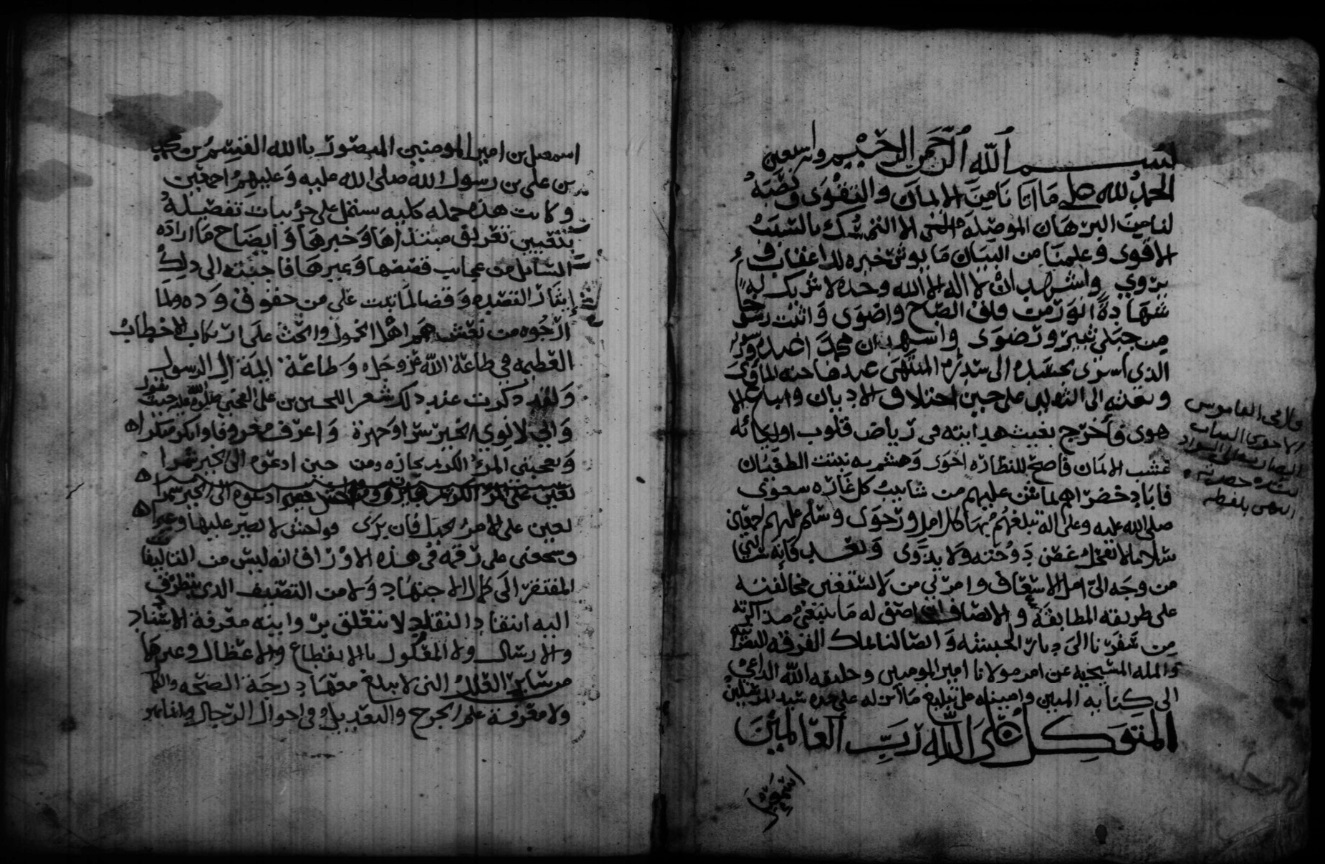

Two copies of al-Ḥaymī’s travel narrative, Sīrat al-Ḥabashah, were collected in Yemen by Eduard Glaser and donated to the Austrian National Library in 1894 (Cod. Gl. 149 and 188). These manuscripts were microfilmed by HMML in 1971 (25502 and 25420) and were recently scanned for online viewing in partnership with the Zaydī Manuscript Tradition project.

The text is a testimony to the possibilities and perils of relations between Christian and Muslim states—each with its own kaleidoscope of Jewish, Christian, and/or Muslim minority groups—struggling on the periphery of far more powerful Christian and Muslim empires. Al-Ḥaymī’s concluding thoughts on the matter are: “There is no power and no strength save in God.”