Thread, Pattern Sheets, And Coverings In West African Manuscripts

Thread, Pattern Sheets, and Coverings in West African Manuscripts

This story is part of an ongoing series of editorials in which HMML curators and catalogers examine how specific themes appear across HMML’s digital collections. From the Islamic collection, Dr. Ali Diakite and Dr. Paul Naylor have this story about Textiles.

West Africa has long been a site of textile production. Cotton has been grown in the region for centuries, and traditionally the Sahel was a prime area for animal husbandry and the raising of cattle. Cattle hides are still used to produce leather today and, because of the hot climate, cotton is the preferred material for garments. Tailors are always accessible and in demand to create traditional outfits—colorful dresses and two-piece suits in a diverse range of patterns.

In the Sahel region today, dyeing and leatherworking remain important occupations. In rural areas, leather drinking vessels and prayer mats (Sali golo) can still be encountered. Decorative boxes made from leather are common items for sale in the tourist trade, and leather is also used to make covers for manuscripts.

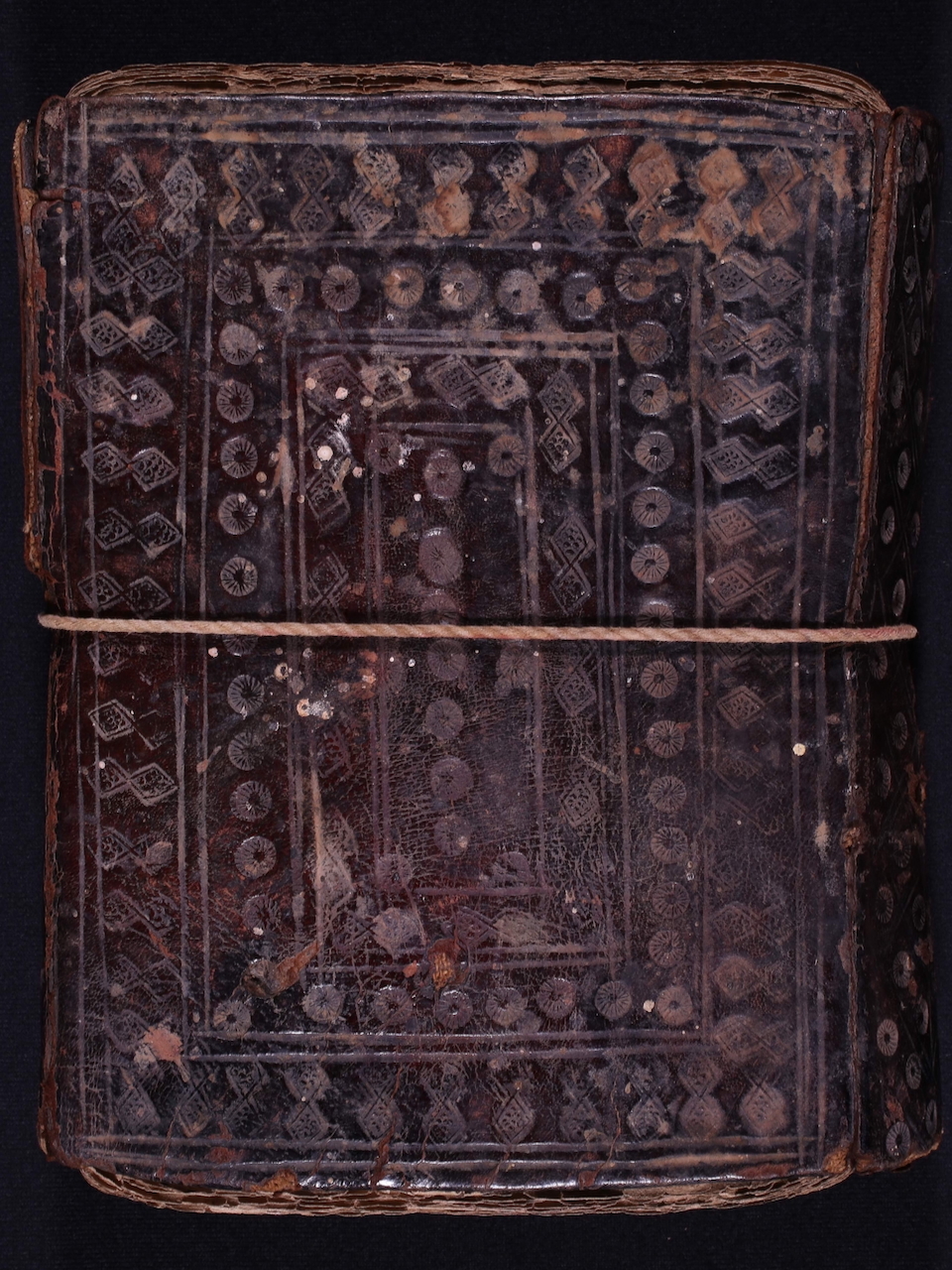

HMML’s collections photographed in Timbuktu, Mali, contain numerous examples of such covers. Because West African manuscripts are traditionally unbound, leather covers are important to keep the pages of the text block together and to protect the paper from damage. For example, the leather covering of manuscript ELIT 04970 encases the third volume of al-Bukhārī’s hadith collection. Here, we can see how the thick leather binding has shielded the textblock from the extremes of climate and insect damage.

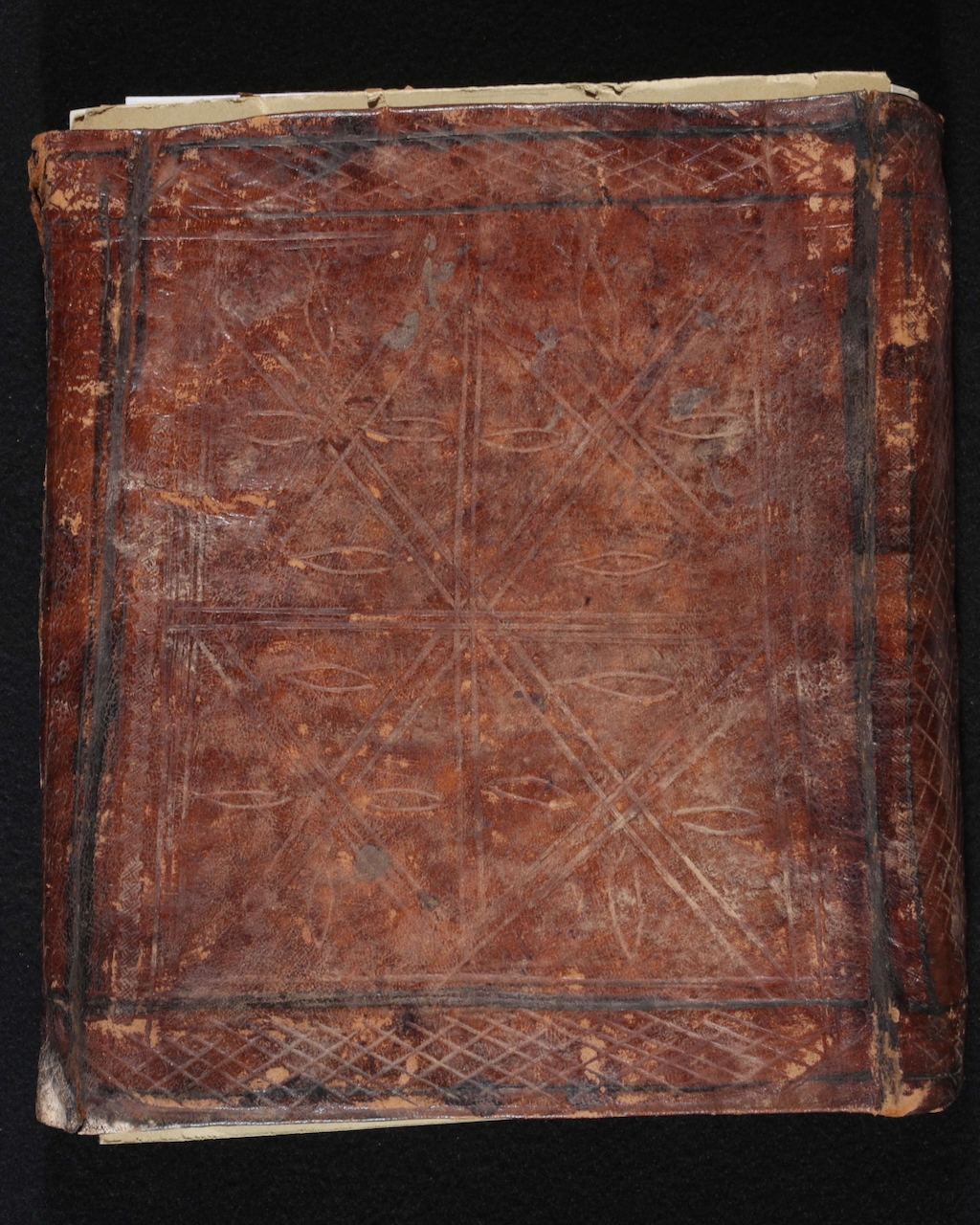

Leather covers are also spaces for demonstrating artistic finesse. The cover of manuscript SAV BMH 16797, a copy of the Qur’an, is embossed with various stamps.

While ELIT AQB 00332 features an etched design around the edges and in the central panel.

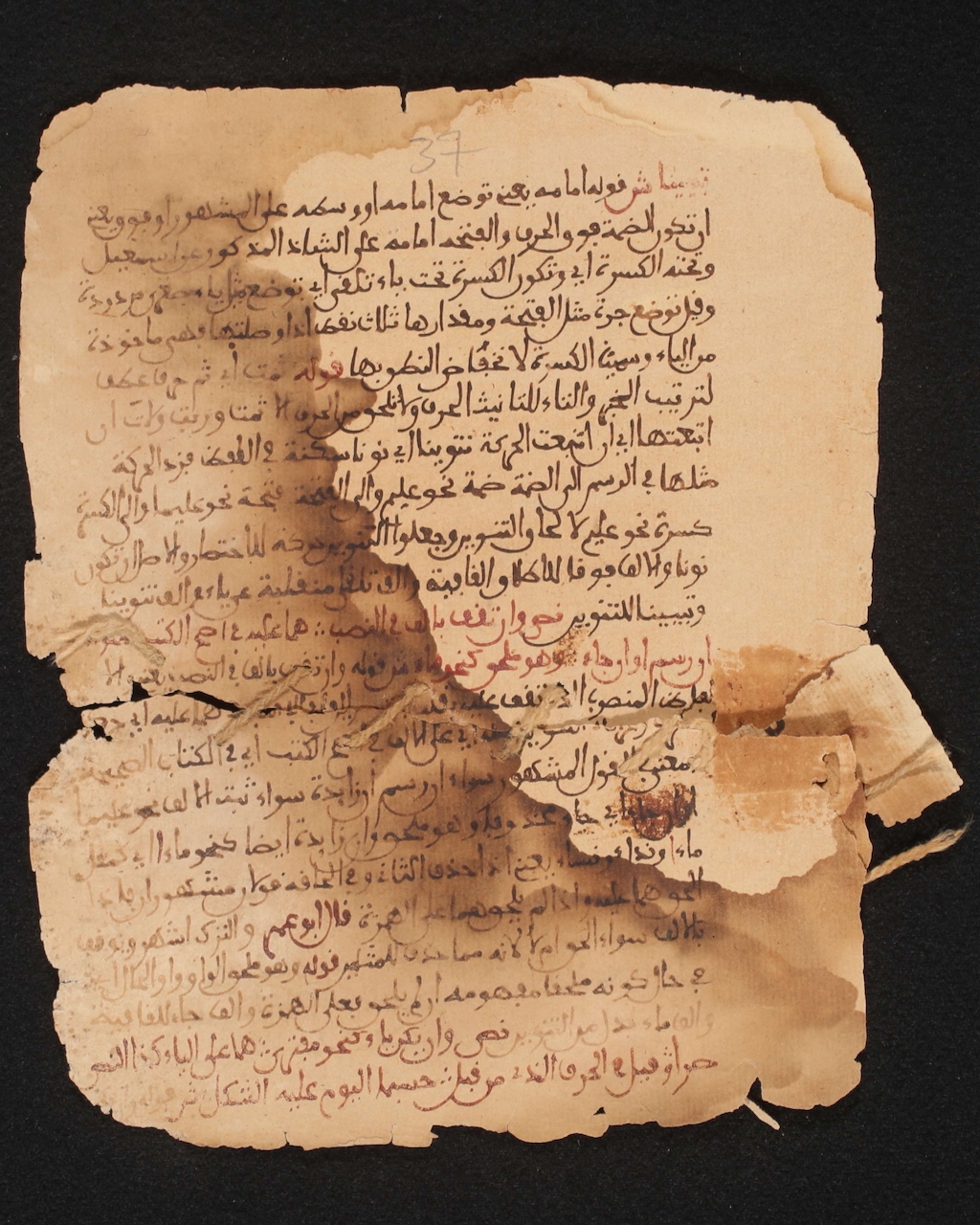

We see hints of the ubiquity of cotton in various repairs made to manuscript pages, employing a diverse range of threads. One example is ELIT ESS 01426, where a blue thread has been used to stitch broken pages back together.

A more curious case is ELIT AQB 03384, where a fragment of paper seems to have been used to anchor the stitching used in the repair of the page.

We see considerable overlap between the designs found in West African textiles and the decorations used on pages of West African manuscripts. Geometric patterns similar to those in West African textile traditions—such as Bògòlan, a Malian tradition of mud-dyed cloth—are often encountered in decorated copies of the Qur’an and other important texts. These full-page designs, which we are calling pattern sheets, typically serve as headings at the beginning or end of the text or are used to mark internal divisions within it.

The similarities are all the more apparent since the dyes used for cloth and the inks used for manuscript writing both contain pigments derived from local soils and clays. A fascinating aspect is that the different patterns used in Bògòlan, Adinkra, and other textile traditions from West Africa have imbued symbolic meanings. It remains to be seen whether manuscripts decorated in this way are also communicating a second message via these patterns.

We hope we have brought attention to the various similarities between the design of manuscripts, textiles, and even architectural elements of West African provenance, and we hope you will explore more on this subject!