Want To Marry The Princess? Know Thy Bible!

Want to Marry the Princess? Know thy Bible!

This story is part of an ongoing series of editorials in which HMML curators and catalogers examine how specific themes appear across HMML’s digital collections. Following a Story Time theme, Dr. Vevian Zaki shares this tale from the Eastern Christian collection.

Who hasn’t heard a fairy tale about a princess whose beauty moves the richest and most handsome bachelors to compete for her hand in marriage? These tales are known in different traditions, but they usually all prescribe that the hopeful suitor overcome a number of obstacles to achieve his goal. He might need to free his princess from a high tower in which she is imprisoned, or from a magic spell that has been cast on her, or even to solve an impossible puzzle to win her heart.

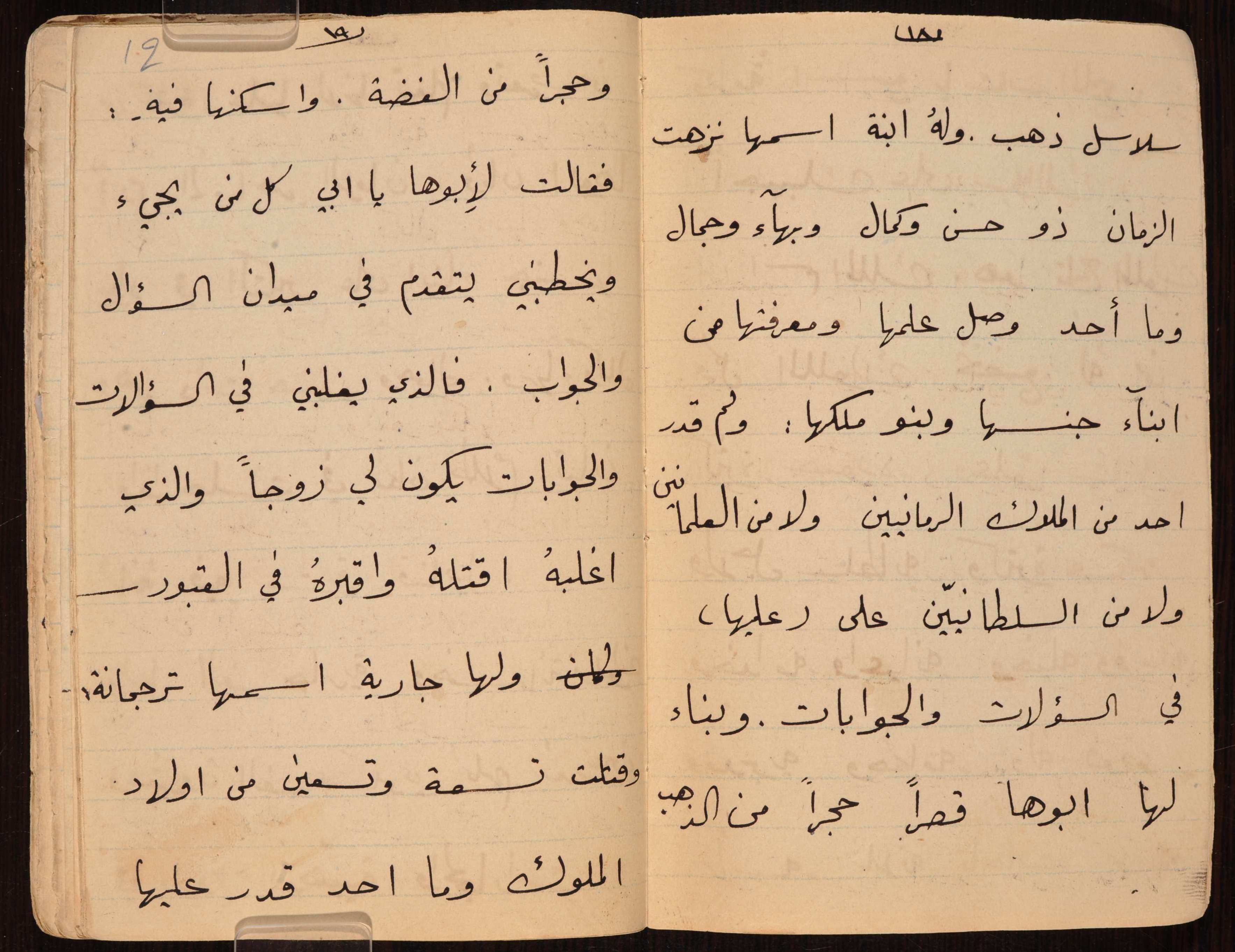

The fairy tale in the spotlight today is found in several manuscripts in HMML Reading Room, written in Arabic, Arabic Garshuni, and Syriac. Here we’ll focus on the Arabic copies.

The main thrust of the tale is as follows: the prince, Sayf al-Masīḥ (Sword of Christ), has to answer a long list of questions in order to win the hand of his princess, Uʻjūbat al-Anām (Wonder of People) or, in some versions, Nuzhat al-Zamān (Pleasure of Time). If all goes well, their marriage will proceed. However, should he fail to answer the questions, he will meet his death.

But let’s rewind to the beginning of our tale. The prince, Sayf al-Masīḥ, is the son of a great king. The family must flee for their lives after the invasion of another powerful king and, as a result, Sayf al-Masīḥ is forced to sell his disguised parents to a third king for their safety. The prince goes forth to travel and adventure alone until he finally arrives at a city where he learns about the gorgeous princess and the tall order her prospective husband must fulfil.

The second part of the story narrates the details of the ordeal that Sayf al-Masīḥ goes through in a bid to win her hand. Despite knowing of the many men who tried earlier and failed—and, indeed, despite warnings from the city judge, the king, and the princess herself—he decides to take the risk anyway.

This part of the tale provides glimpses into the setting of the story and its transmission. Although the several copies in the Arabic language differ in some ways, all agree that the story takes place in a Christian, European milieu: the kings in the tale rule Italy, Spain, or Rome, and there is always a patriarch who accompanies the royal family and has a say in the incidents that unfold. The royal family and the prince also attend a morning mass.

Perhaps an even more important testament to this Christian setting is the set of questions posed by the princess Uʻjūbat al-Anām in the competition. Her questions are based almost exclusively on knowledge of the Bible. The transmitter of this tale was evidently well acquainted with the biblical narratives.

Some questions are straightforward. For example: what constitutes the moving tomb with a live person inside? The prince immediately answers: the tomb is the whale, which traveled with the prophet Jonah inside. A second, slightly easier, question asks which land was exposed to the sunshine only once. Sayf al-Masīḥ again successfully responds that it is the land of the Red Sea that surfaced when God drove the sea back and the waters were divided; then the Israelites walked on it and were saved from Pharoah (Exodus 14:21–22). Another question is posed: two thieves; one was happy and the other was miserable, who were they? The prince correctly answers that they were the thieves crucified with Jesus (Luke 23:32–43).

Other questions are increasingly tricky, focused on scenarios in which the biblical narrative is vague, inconclusive, or susceptible to more than one interpretation. In any case, the reader will be relieved to hear that Sayf al-Masīḥ is able to answer each question correctly.

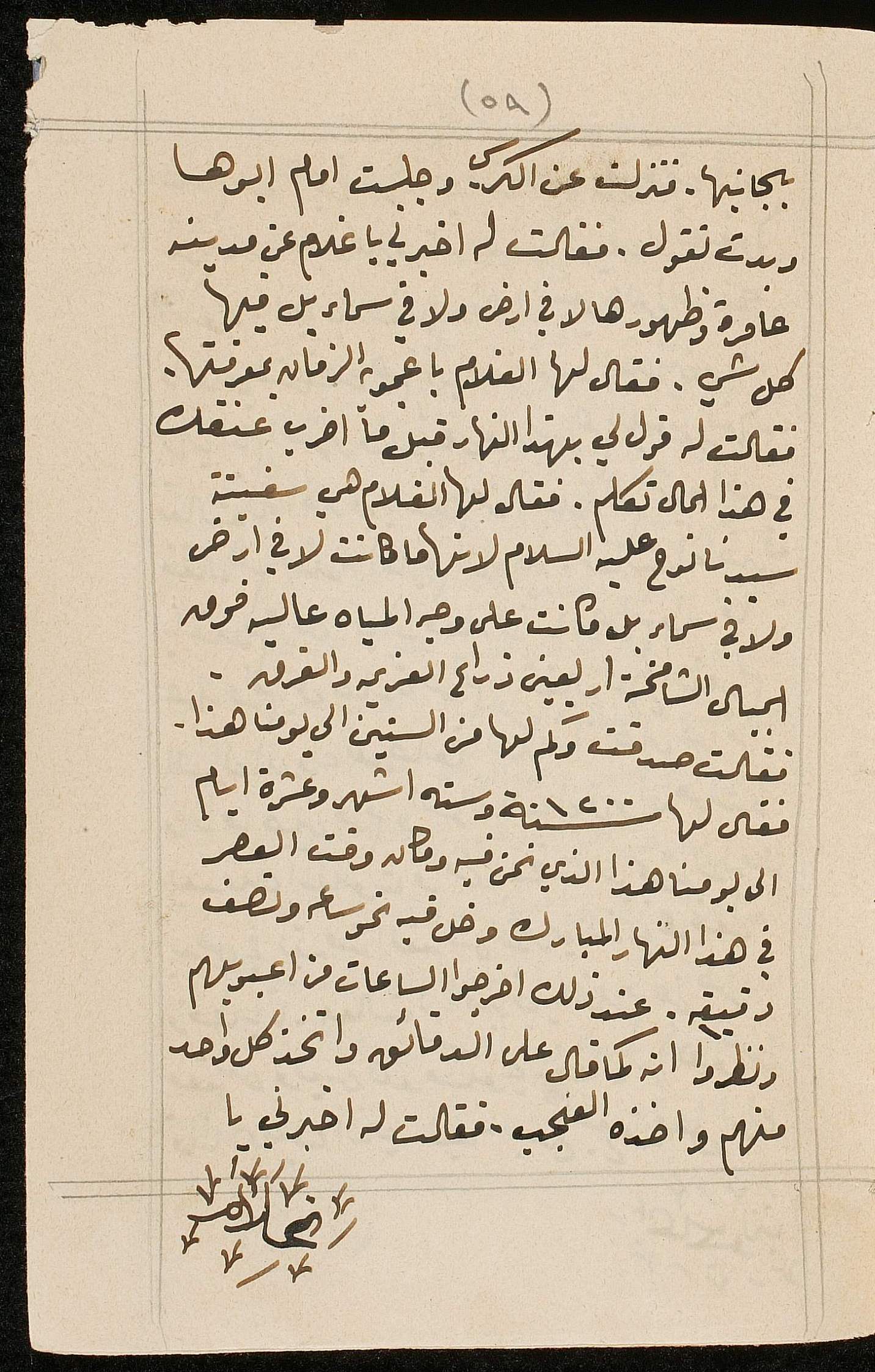

Some of the prince’s answers differ slightly from one Arabic manuscript to another. For instance, when the Uʻjūbat al-Anām asks the prince about the number of the Israelites who descended to Egypt, and their number at the Exodus, the numbers in the prince’s response vary slightly among manuscripts. And when she asks about the amount of time that has elapsed from the flood of Noah until now, Sayf al-Masīḥ answers in one version: 2200 years, 56 months, ten days, four and a half hours, and ten minutes (SCAA 00007 211 and PLB HR 00001). Yet in another version, he answers: 1200 years, six months, ten days, one and half hours, and ten minutes (CFMM 00904).

It is unclear which kind of calendar computations, if any, were used to concoct the prince’s answers to the flood question, but evidently the computations follow different traditions. The story goes that, on hearing his answer, the spectators brought out their watches from their pockets and confirmed that the time calculations of Sayf al-Masīḥ were indeed correct. So, we can infer that the tale was written—or at least that detail was added—at a time when the use of pocket watches was known.

As already revealed, Sayf al-Masīḥ successfully answers all the questions. Following this long and difficult scrutiny of his biblical knowledge, other events conspire to prove his noble origins and return to him his lost kingdom.

This plot of this tale recalls a story from the Arabian Nights that goes along the same lines—Linguist-dame, the Duenna and the King’s Son (see CFMM 00297 and SOAA 00121 K). While the questions in the Arabian Nights version bear traces of Islamic as well as Jewish/Christian traditions, the tale of Sayf al-Masīḥ is fully Christianized and is a later transmission.

True to all the versions, however, the end of the fairy tale is always happy: the prince prevails and wins over his beloved princess.