Ottoman Soap Operas And Other Stories

Ottoman Soap Operas and Other Stories

This story is part of an ongoing series of editorials in which HMML curators and catalogers examine how specific themes appear across HMML’s digital collections. Following a Story Time theme, Dr. Josh Mugler shares this tale from the Eastern Christian and Islamic collections.

HMML’s digital collections include entertaining stories from a wide range of linguistic and religious traditions. Some of the most intriguing stories occur in various forms of Ottoman Turkish, found in the collections of both Christian and Muslim libraries. The Turkish language underwent intense reforms in the early 20th century under the rule of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, altering the writing system and vocabulary, so these manuscripts are valuable witnesses to the Turkish that was spoken in past centuries. They preserve dialect features that were used by ordinary people, often quite different from the literary Turkish used in the scholarly discourse of Constantinople.

For example, manuscript DFM 00332 in the collection of the Dominican Friars of Mosul preserves notes on Turkish grammar and stories collected by the French Orientalist and Vincentian missionary Pierre François Viguier (1745–1821). Most of these stories were relayed to Viguier by a Constantinopolitan interlocutor named Meddah (“storyteller”) Ali Efendi.

The reader is given a sense of the social context of these stories when Viguier describes them in French as “contes du Ramazan,” or “Ramadan stories,” indicating that they were used to entertain audiences during the long and hungry days of the Ramadan fast, precursors of the Ramadan soap operas that now appear on television every year. Viguier provides French translations of the stories and records the Turkish in Roman script, which means that in addition to colloquial Turkish vocabulary, they provide us with invaluable information on pronunciation that could be masked by Arabic-script spelling conventions.

Many Ottoman Turkish tales narrate the lives of heroic figures from pre-Islamic and early Islamic history. Pre-Islamic characters include the legendary Iranian rulers Fīrūz Shāh (AKDI OTH 0017, Khalidi Library) and Bakhtiyār (CFMM 00975, Church of the Forty Martyrs). The latter story also appears frequently in Arabic (where the main character is called Āzādbakht) and features a king whose long-lost son is accused of impropriety and sentenced to death by ten viziers. The prince delays his execution by telling a new engrossing story each night until his father recognizes him and restores him to power.

Another popular narrative is set in the early Islamic context and centers on Ḥamzah, the Prophet’s uncle and a renowned warrior who died in one of the first major battles of Islamic history (see CFMM 00977, Church of the Forty Martyrs). Other members of the Prophet’s family appear in these stories, such as his son-in-law ʻAlī, who is also the main character of some colorful legends in which he fights a dragon and a giant and speaks with an angel who appears in the form of a pigeon (AABL 00187 164, al-Zāwiyah al-Uzbakīyah). The Mar Behnam Monastery collection includes the story of al-Mukhtār al-Thaqafī, who led a rebellion to avenge the death of the Prophet’s grandson Ḥusayn at the Battle of Karbalāʼ (MBM 00345). Many of these stories entered the Turkish oral tradition from Arabic or Persian as the Turks converted to Islam, and they helped to convey important information about the religion’s origins for those who were new to it.

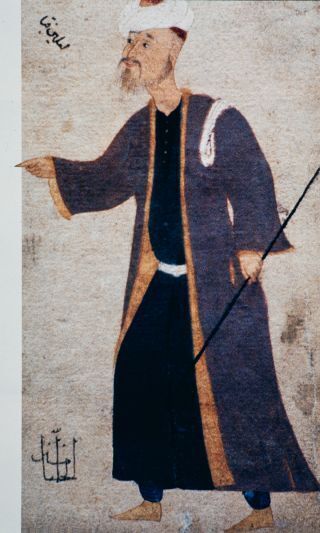

My personal favorite of these Turkish folk tales, however, is found in manuscript CFMM 00974 at the Church of the Forty Martyrs in Mardin, Turkey. This manuscript does not feature characters from ancient history or from the dawn of Islam, but instead focuses on a well-known medieval figure: Ibn Sīnā, known in Western Europe as Avicenna and in the Turkish folk tradition as Ebû Ali Sînâ. The historical Ibn Sīnā of the 10th and 11th centuries was one of the most celebrated philosophers, physicians, and natural scientists of the medieval Islamic world, and his Arabic Canon of Medicine (al-Qānūn fī al-ṭibb) became perhaps the most influential medical textbook in world history.

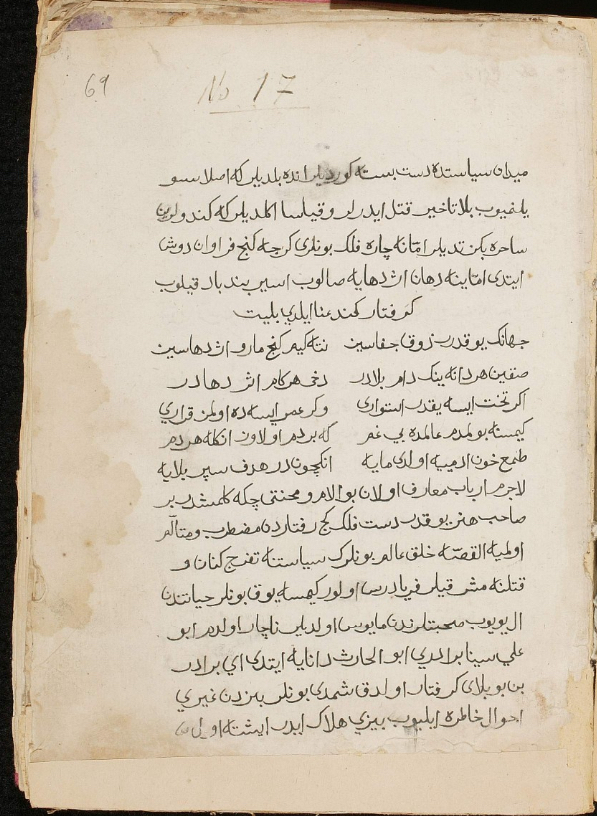

In these Turkish stories, however, Ebû Ali is essentially a sorcerer, and he gets into various adventures and hijinks with his brother Ebü’l-Hâris. The tales come from a context in which people knew the power of science for good or for ill, and they remembered Ebû Ali Sînâ as a figure who could wield his scientific abilities in a truly awe-inspiring and quasi-magical way. The most famous version of the narrative is known as Esrâr-ı Hikmet (Secrets of Wisdom) and is attributed to a storyteller known as Derviş Hasan Medhî (from the same root as Meddah, mentioned above), who likely lived around the 16th century. CFMM 00974 includes only fragments, but it provides one previously unknown witness to this entertaining collection. A more complete version is found in HMML's microfilm 23297 (Cod. Mixt. 807, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek).

The people of the Ottoman Empire had a rich storytelling tradition, and while much of this tradition has been lost, these manuscript collections help us understand the ways that they found amusement in their daily lives.