Parabiblical Literature In The Horn Of Africa

Parabiblical Literature in the Horn of Africa

This story is part of an ongoing series of editorials in which HMML curators and catalogers examine how specific themes appear across HMML’s digital collections. Following a Story Time theme, Ted Erho shares this tale from the Eastern Christian collection.

Biblical narratives often leave the audience wanting to know a bit more. From where did the giants in Genesis chapter 6 come? How did Abraham and Sarah react after their son Isaac barely escaped being sacrificed? What happened to the prophet Isaiah after his final conversation with King Hezekiah?

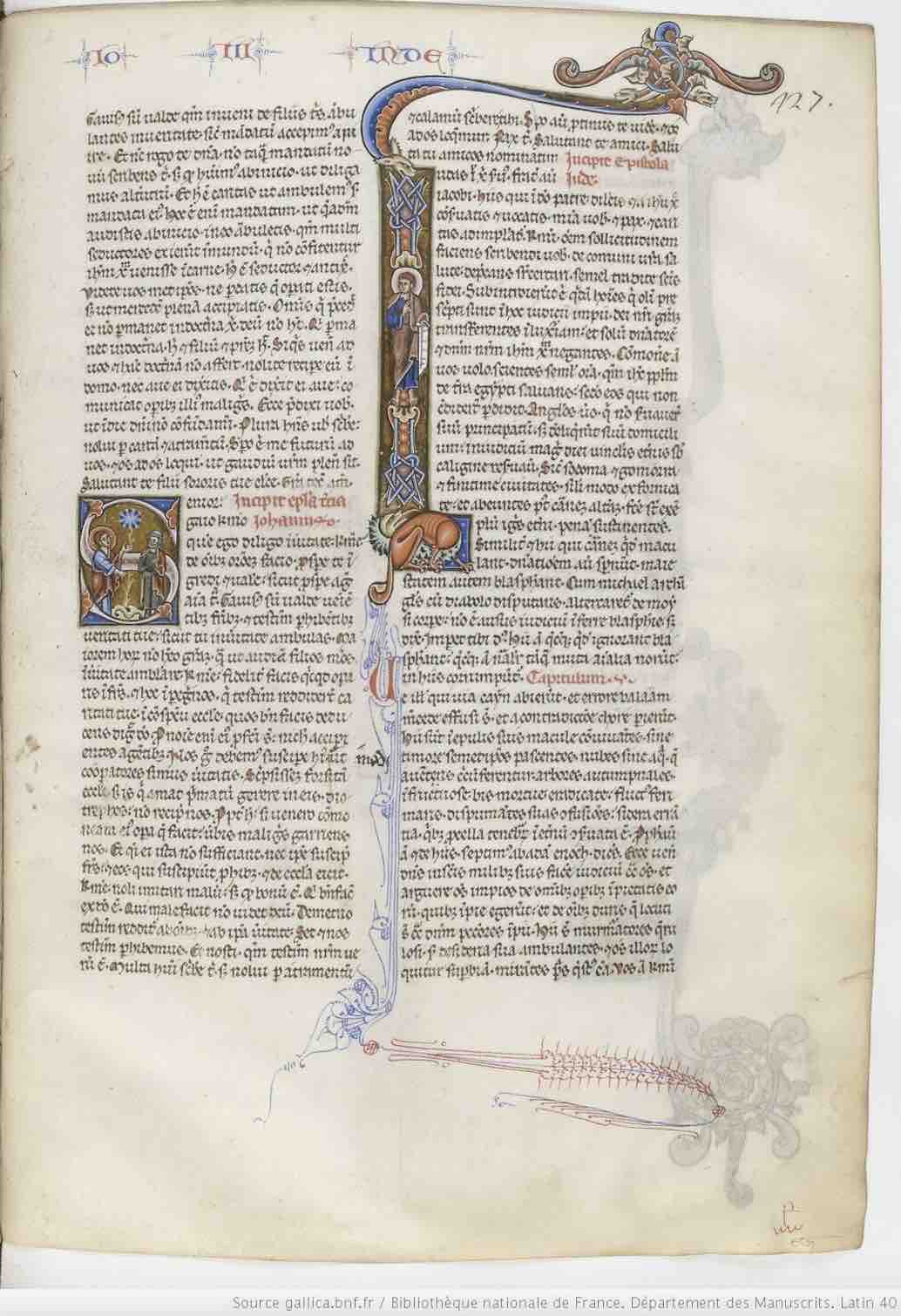

Long ago, answers to questions like these circulated throughout the ancient world in books such as Enoch and the Ascension of Isaiah, works now often referred to by scholars as parabiblical literature. During the lifetime of Jesus and in the early church, many such works were extremely influential, as attested, for example, by the quotation from Enoch in the Epistle of Jude (verses 14-15):

Enoch, the seventh from Adam, prophesied about them: “See, the Lord is coming with thousands upon thousands of his holy ones to judge everyone, and to convict all of them of all the ungodly acts they have committed in their ungodliness, and of all the defiant words ungodly sinners have spoken against him.”

Despite their early popularity, however, most works of this type eventually began to fade away. Text by text, community by community, they were lost from Jewish and Christian circles, gradually forgotten or quickly suppressed. And for centuries, they passed out of all knowledge—in most of the world.

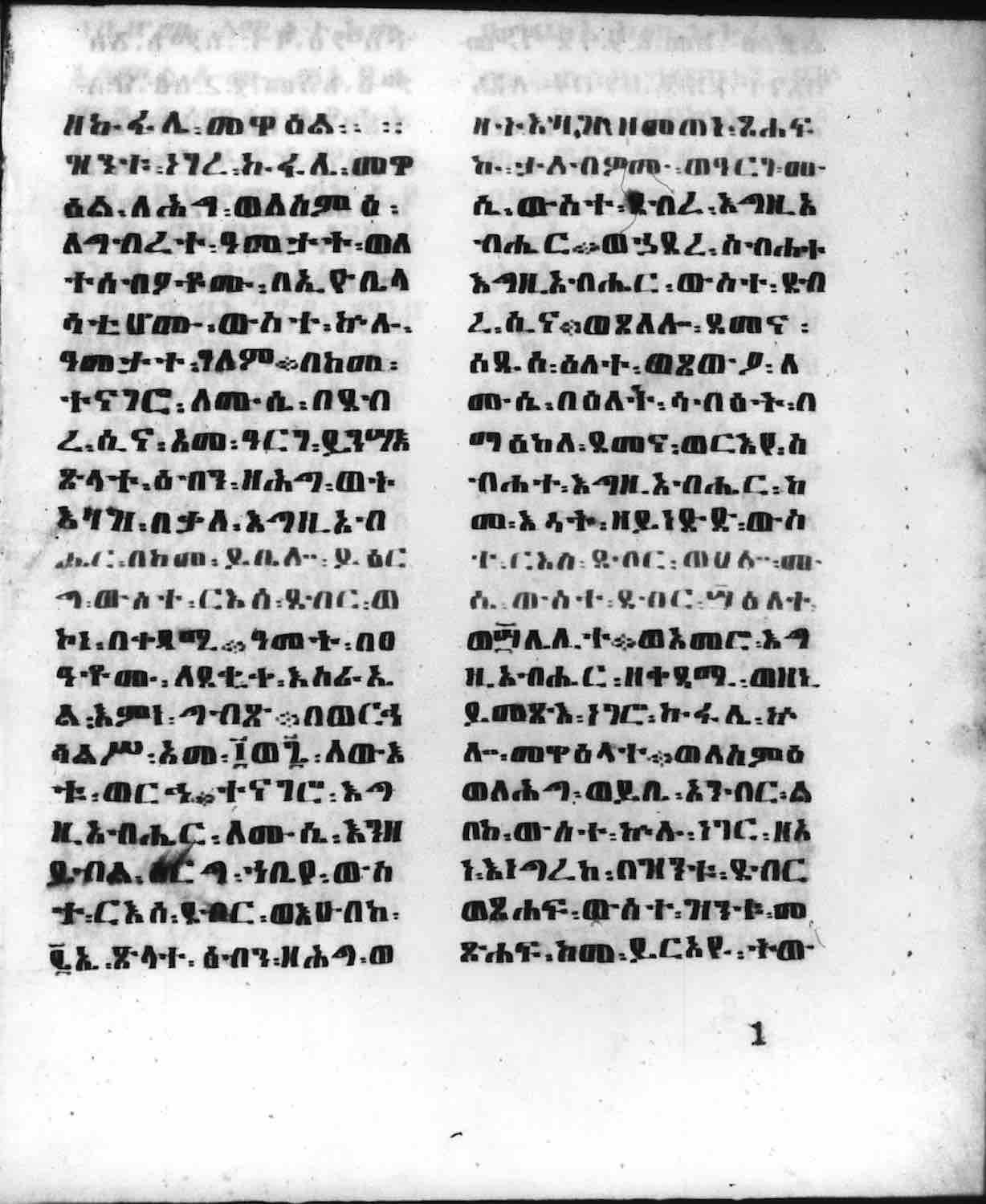

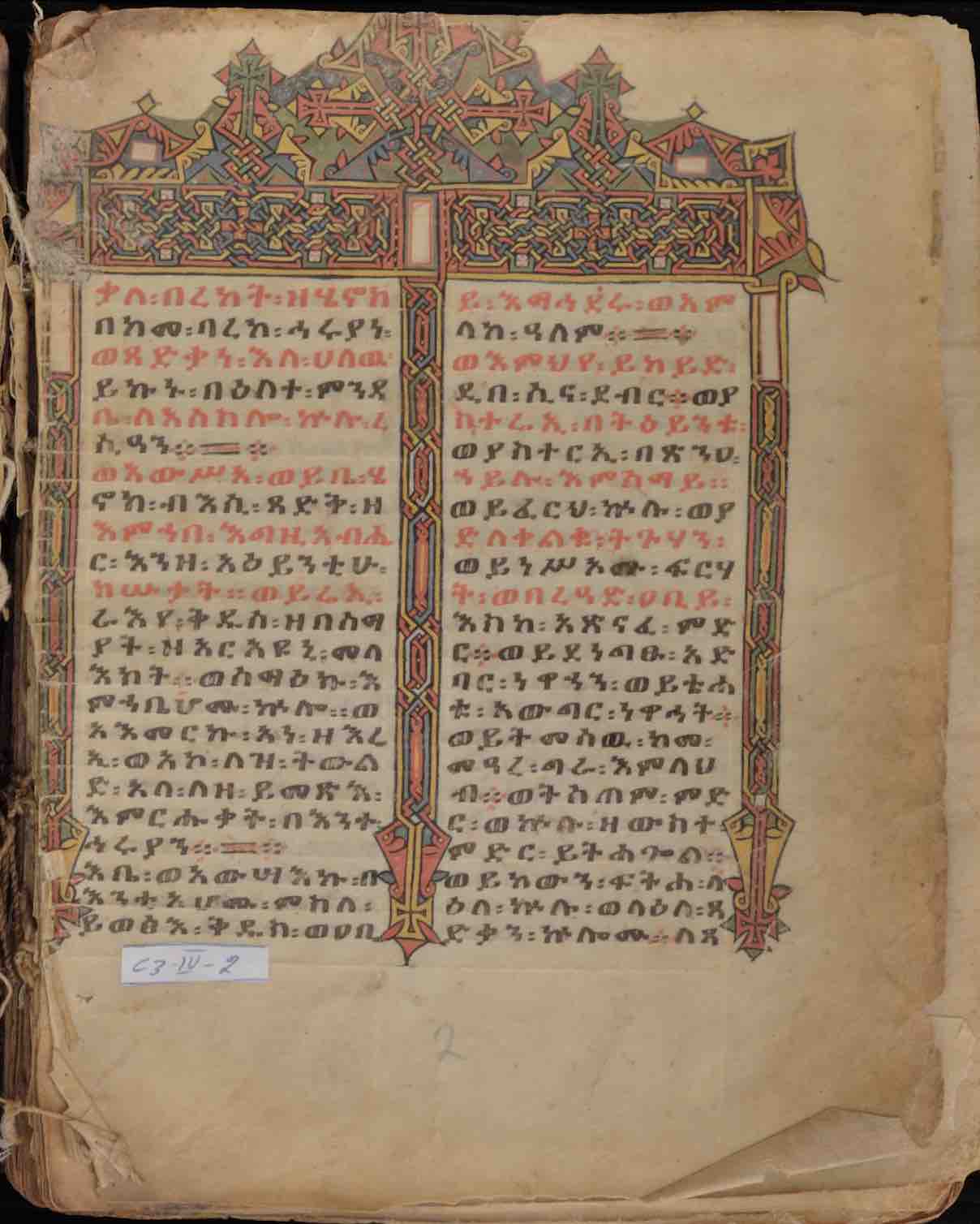

Near the equator, on the rim of Christendom, many such texts continued to be treasured and read. Letter by letter, page by page, countless scribes invested tens of thousands of hours duplicating the texts, overcoming the neglect of the rest of the world. It was not through Jerusalem, Rome, Antioch, or Alexandria, but through the monks of Ethiopia that these important pieces of world history and literature would be saved.

As far as can be determined from the modern vantage point, there seems to have been a particular fascination among Christians in the Horn of Africa with stories related to biblical figures and events. Nearly all Ethiopic literature of this type consists of translations from Greek (in the first millennium) and Arabic (in the second millennium). Only on occasion did these Christians compose such stories themselves, albeit with increasing frequency after the medieval period.

Some of the oldest and some of the most recent translations from Arabic into Ethiopic are of parabiblical texts, spanning a period exceeding half a millennium. Despite often being ignored or overlooked by scholars, a great number of biblical tales are represented, sometimes in unique and unexpected ways.

While among the most famous episodes in the Bible, and an incident told and retold time and again, the account of the binding of Isaac in Genesis 22 is surprisingly cursory, ending rather abruptly and not mentioned for the rest of Abraham’s life.

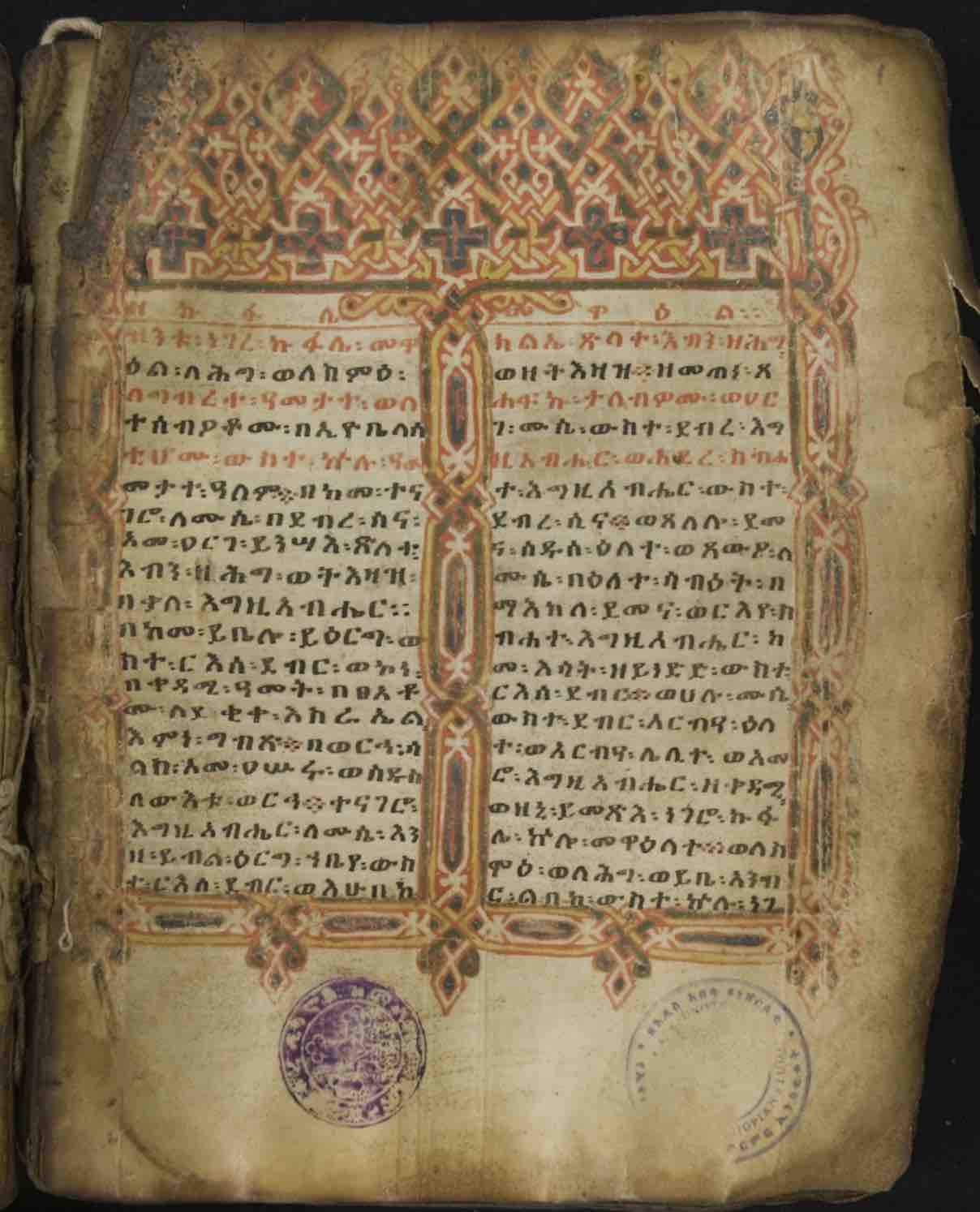

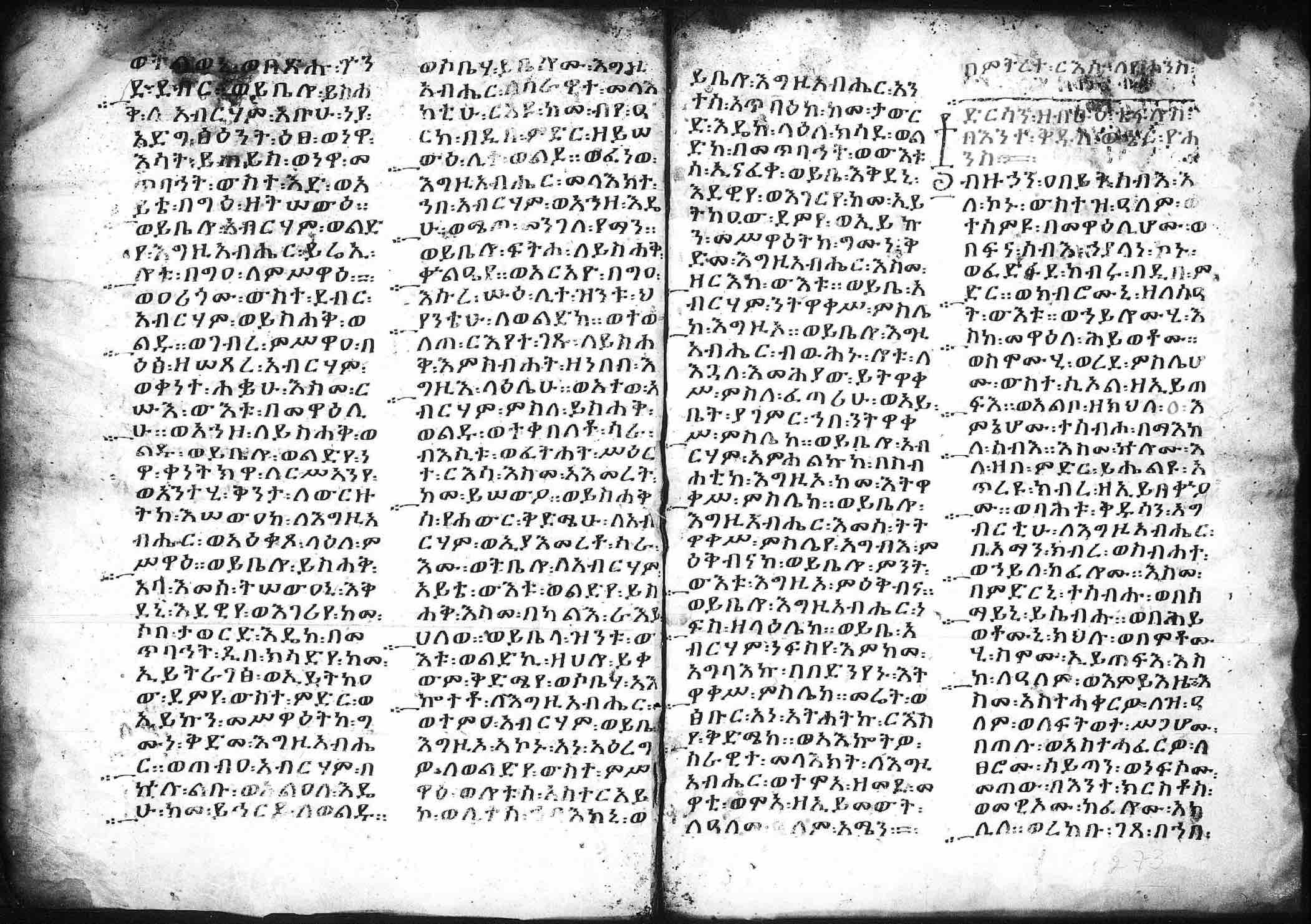

Does a story of life and death, of near human sacrifice, not demand a bit more? Quite a few ancient writers seem to have thought so, and nearly all elements added to the story in their retellings, such as Sarah’s reaction, would be repeated countless times. One of the rare, truly innovative exceptions appears at the end of a short parabiblical text recounting the episode, found in a famous manuscript from the monastery of Ḥayq Esṭifānos, EMML 1763 (fol. 272r-273r). After his return home in this version, Abraham tries to debate God about the justifiableness of his actions:

Abraham said, “Let me argue with you, O Lord.”

The Lord replied, “Why should a mortal be allowed to argue with his creator? And what house will hold me where I might argue with you?”

Abraham said to him, “I adjure you, O Lord, in your glory to let me argue with you.”

The Lord replied, “If you really want to argue with me, hand over your deposit!”

Abraham said, “What is the deposit, O Lord?”

The Lord replied, “Your soul.”

Abraham said, “If I handed over my soul, could I argue with you with my corpse? I am dust and clay, and I humble myself before you.”

Through a somewhat humorous epilogue, this scene adds a further layer of complexity to the story, beginning to hint at the unhappiness of the protagonist and echoing the same confusion and anger voiced over centuries by countless Jews and Christians about how such a terrible thing could have been demanded of Abraham.

Parabiblical works translated from Greek, on the other hand, constitute a far more famous category, not only in the Ethiopian and Eritrean Orthodox traditions, but internationally. The nearly mythical book of Enoch would occupy the attention of several prominent Europeans in the 17th and 18th centuries, ultimately leading the Scottish explorer James Bruce (1730–1794) to recover the “lost” book from Ethiopia—where it had been flourishing for quite some time!

This is only one example of how the West was reacquainted with an important parabiblical work that it, and not others, had lost. As decades passed, further such texts would emerge: Jubilees, a retelling of biblical history to Moses; the Epistula Apostolorum, a post-resurrection dialogue between Jesus and his apostles; the Ascension of Isaiah, a heavenly vision and the martyrdom of the prophet; and several others, all originating in the 2nd century or earlier.

Outside of Ethiopia, many of these texts were known fragmentarily, often in the form of a title and a few excerpts or as surviving pages in various languages, but it was only through the Ethiopic manuscripts that the full texts could be read. To this day, in fact, the only fully surviving ancient version of each of these works remains the Ethiopic, which in each case scribes diligently continued to copy by hand well into the 20th century.

How this enduring interest in the broader stories about biblical figures and events came to be will likely never be fully understood. But the disproportionate amount of parabiblical texts preserved in the Ethiopic tradition makes it clear that they were highly valued. And sometimes the best story is that we still have such stories.