Learning To Write: Practical Aspects Of Handwriting

Learning to Write: Practical Aspects of Handwriting

This story is part of an ongoing series of editorials in which HMML curators and catalogers examine how specific themes appear across HMML’s digital collections. From the Western European collection, Dr. Matthew Z. Heintzelman shares this story about Scribes.

“However useful the findings of the scholar may be, they would never reach posterity without the skill of the scribe. However good our actions, however profitable our teaching, they would all soon be forgotten if the zeal of the scribe did not transform our efforts into letters. It is the scribes who lend power to words and give lasting value to passing things and vitality to the flow of time.”

—Johannes Trithemius, In Praise of Scribes (De laude scriptorium). Translated by Father Roland Behrendt, O.S.B, published in Lawrence, Kansas, in 1974.

In 1492, Johannes Trithemius, the abbot of a Benedictine monastery in Sponheim, Germany, wrote a small paean to scribes and the act of writing. By emphasizing the spiritual value of writing as an activity, he was championing a task that lay at the core of monastic life for centuries.

But how does one become a scribe? Learning to put words to page is one thing, but having aesthetically pleasing handwriting is another. As it happens, the budding printing industry in early modern Europe provided writing masters with a forum in which they could instruct new scribes and calligraphers, as well as demonstrate their own skill with the pen.

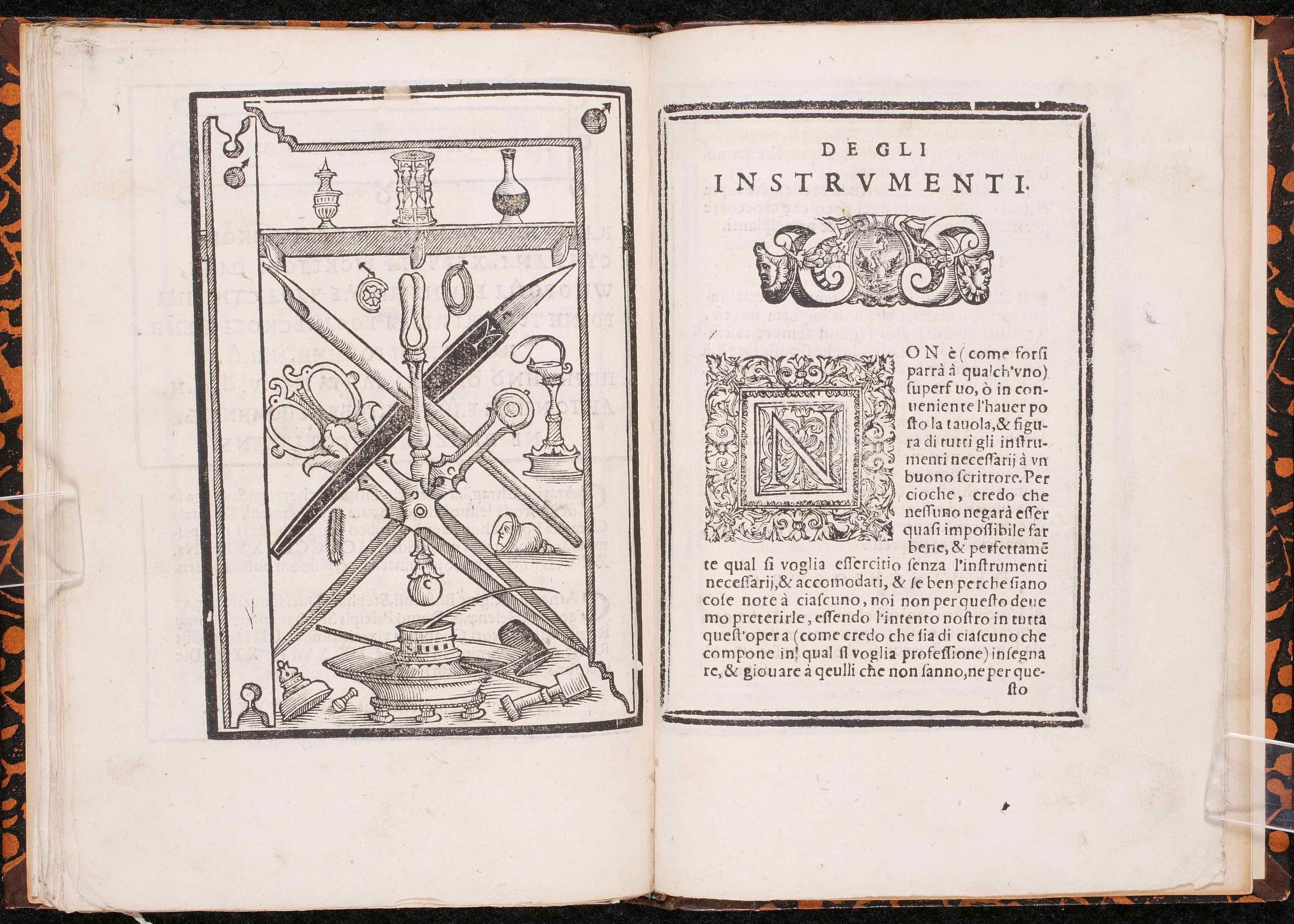

Writing manuals were published, describing the tools of the trade, the proper position for writing, as well as numerous exercises to create beautiful writing. The Arca Artium collection at Saint John’s University contains a wide range of such manuals from 16th- to 19th-century Europe, printed in several languages including German, French, English, Spanish, and Italian.

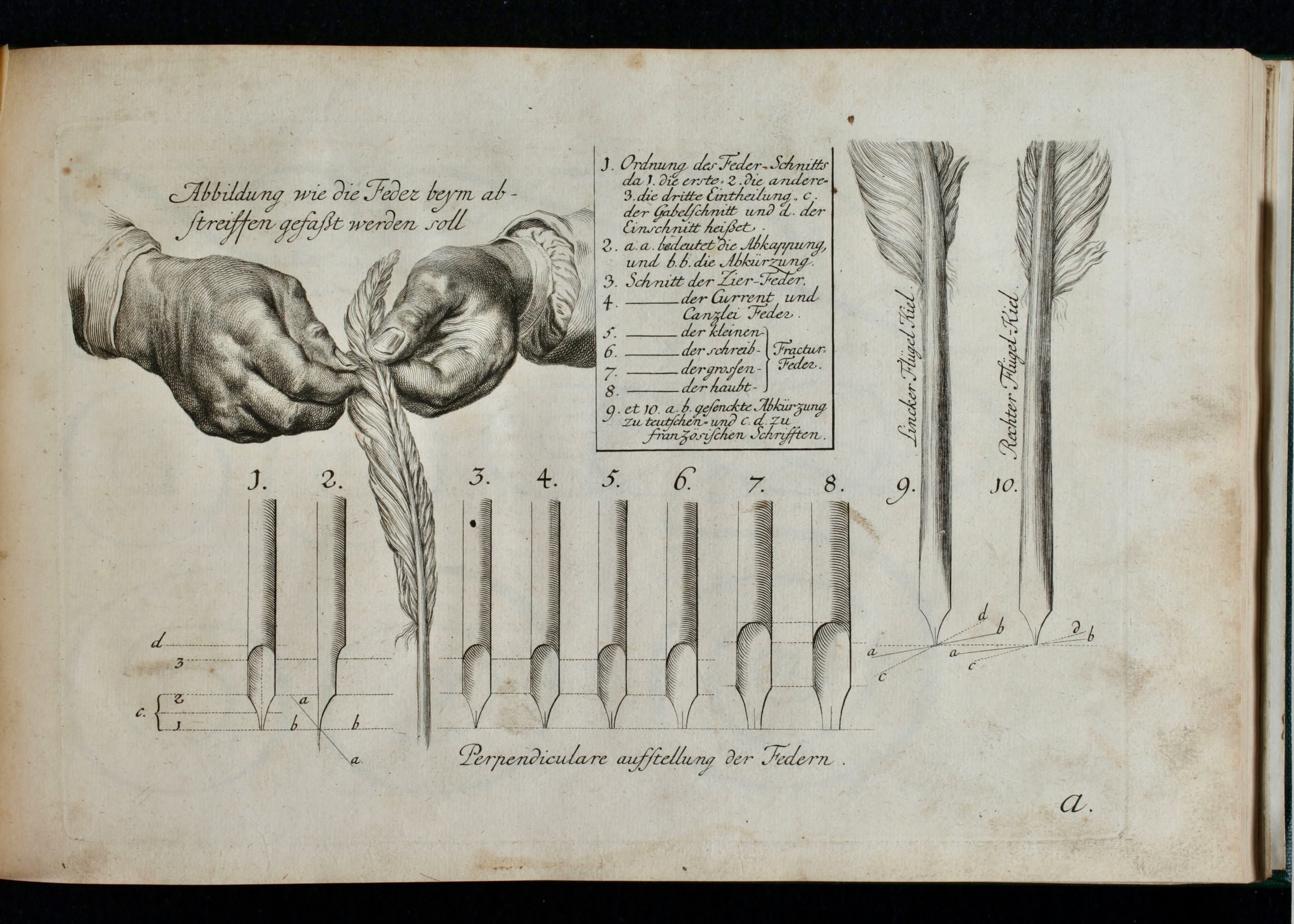

Preparing Tools for the Scribe

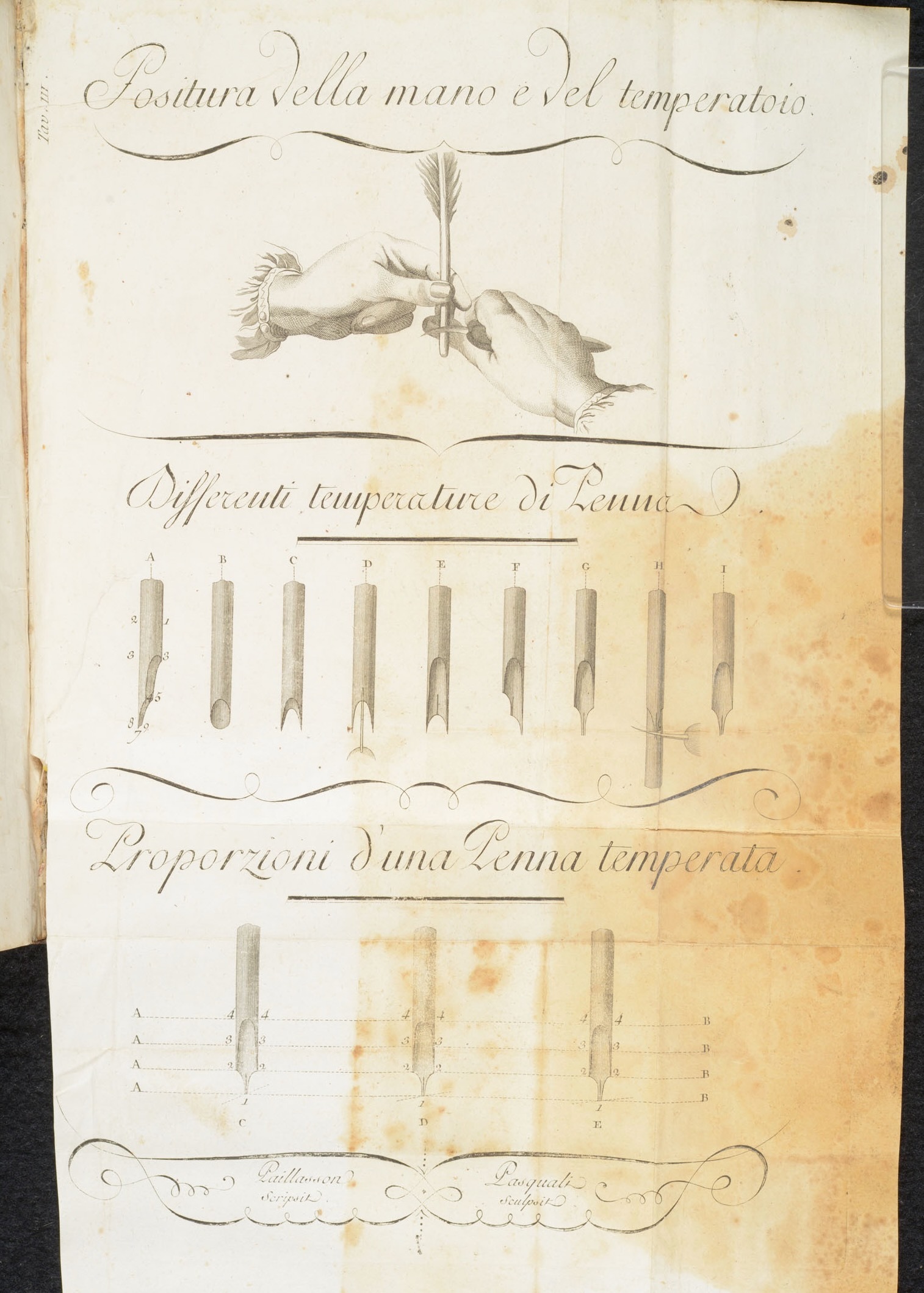

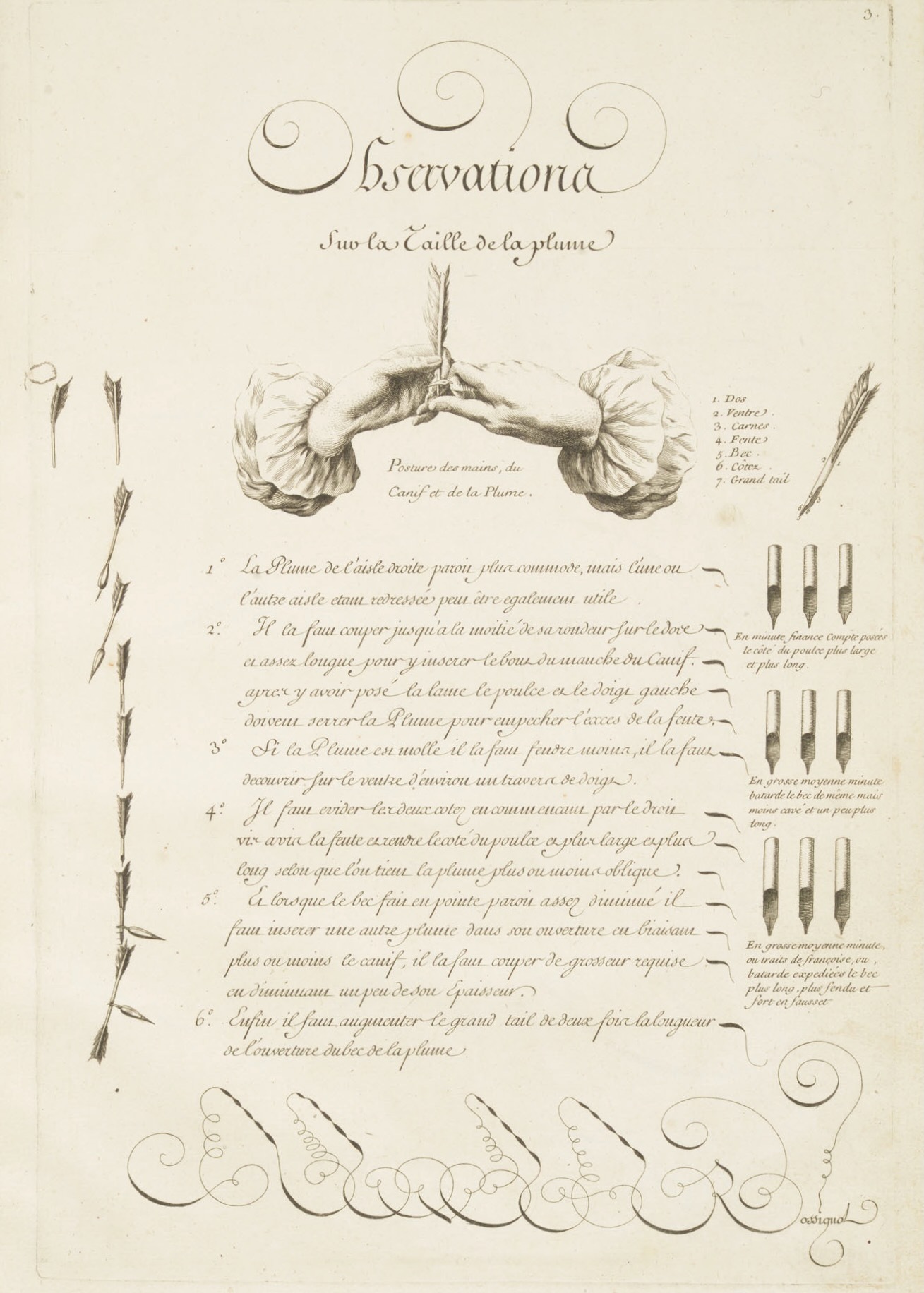

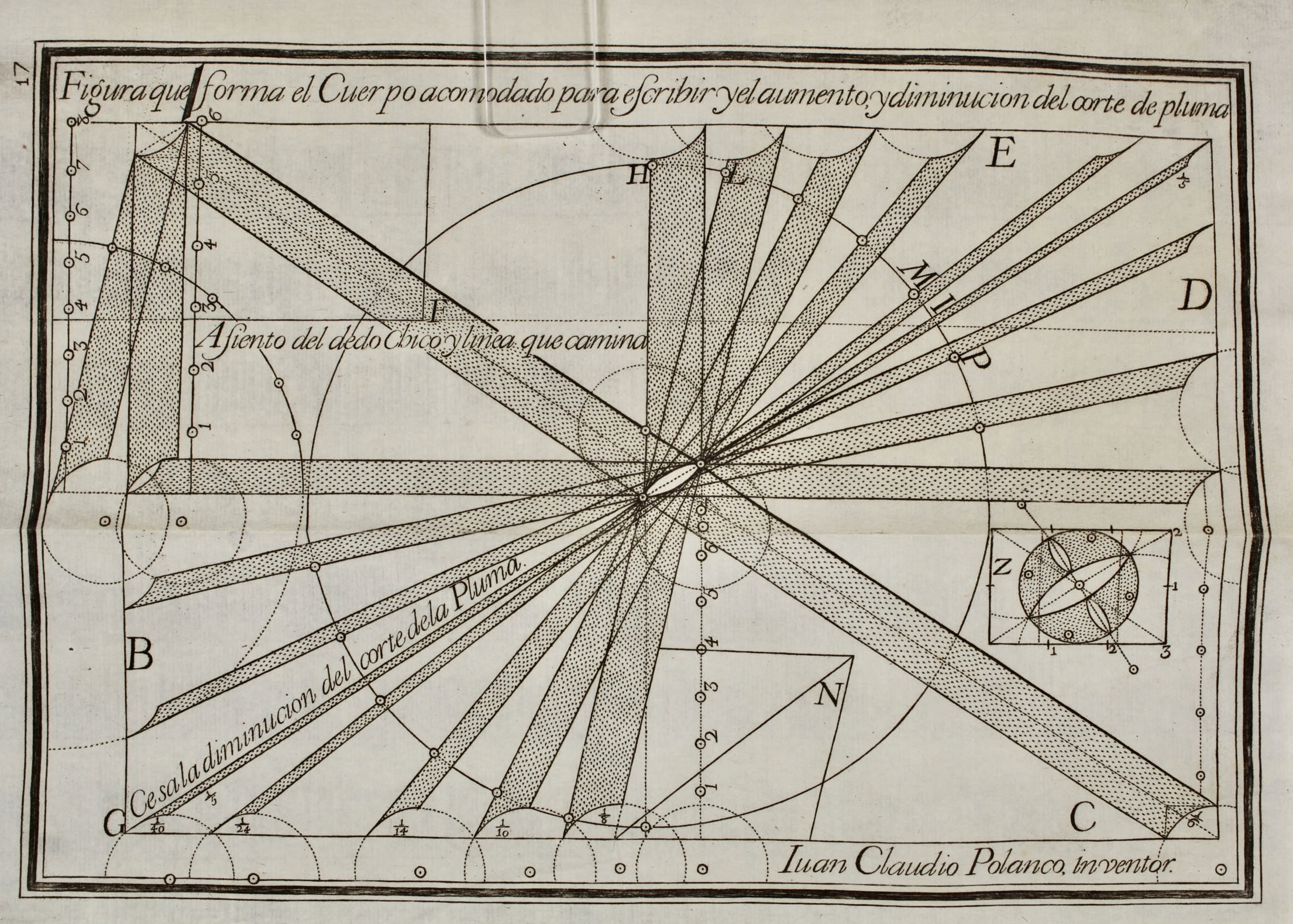

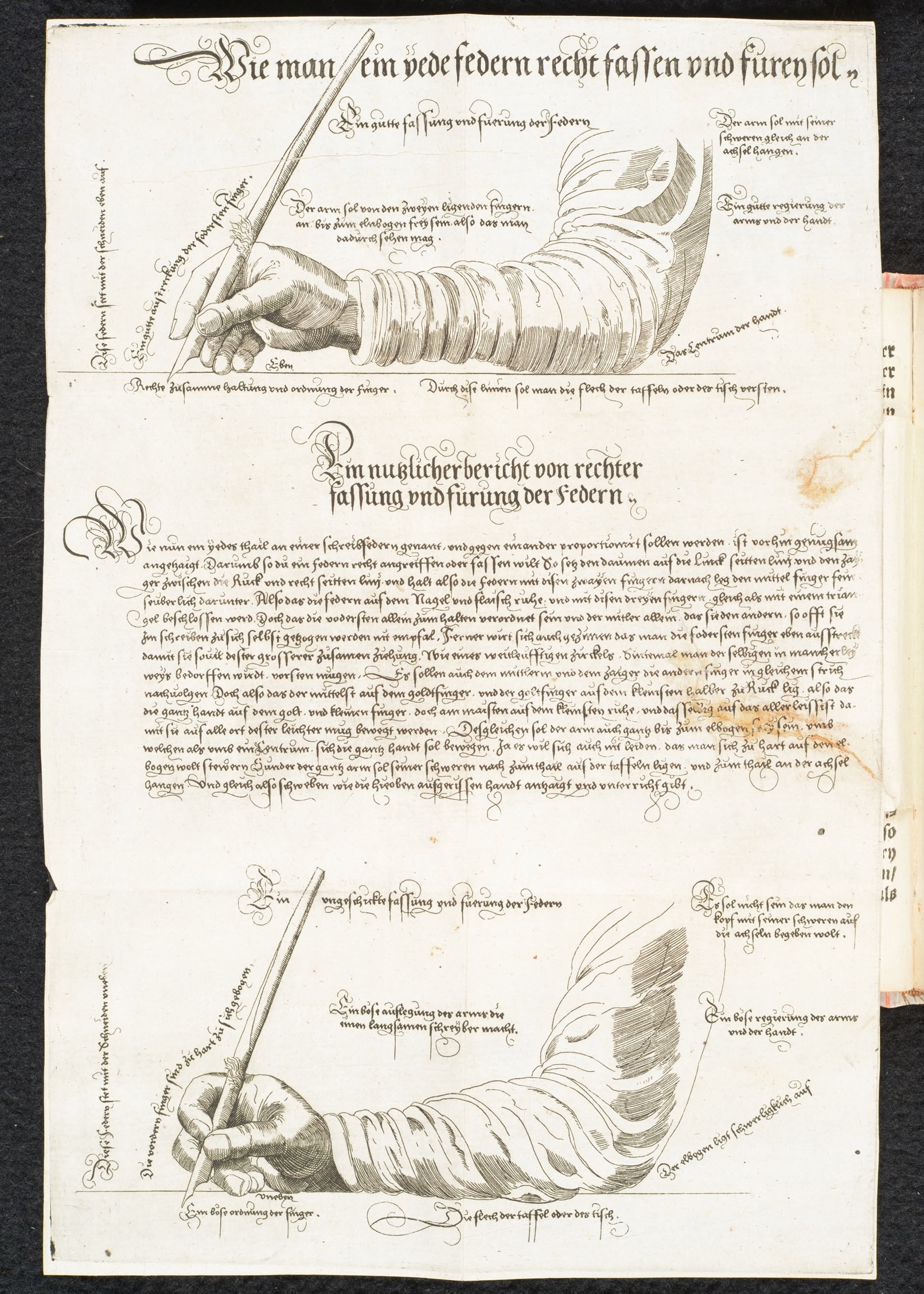

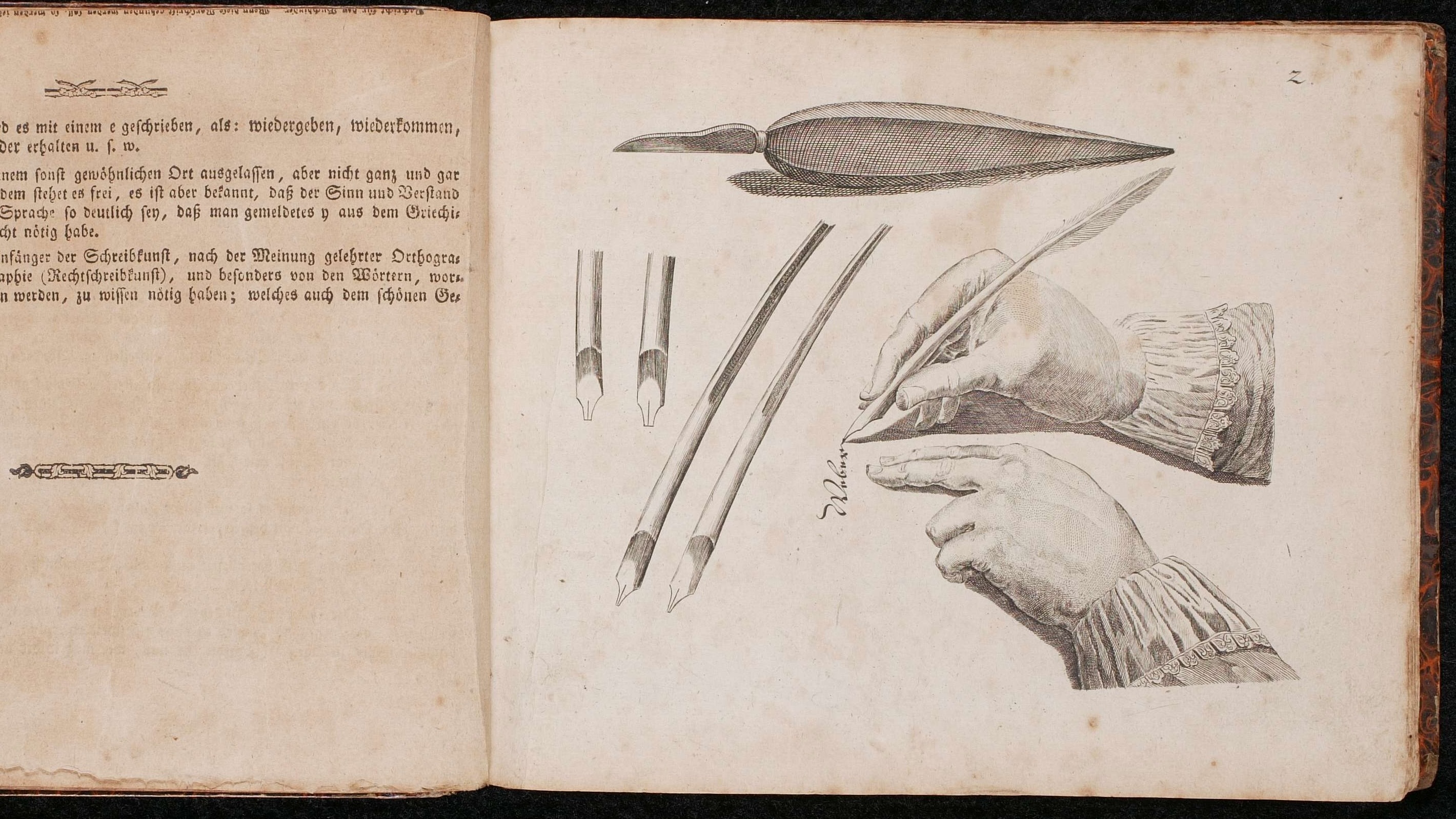

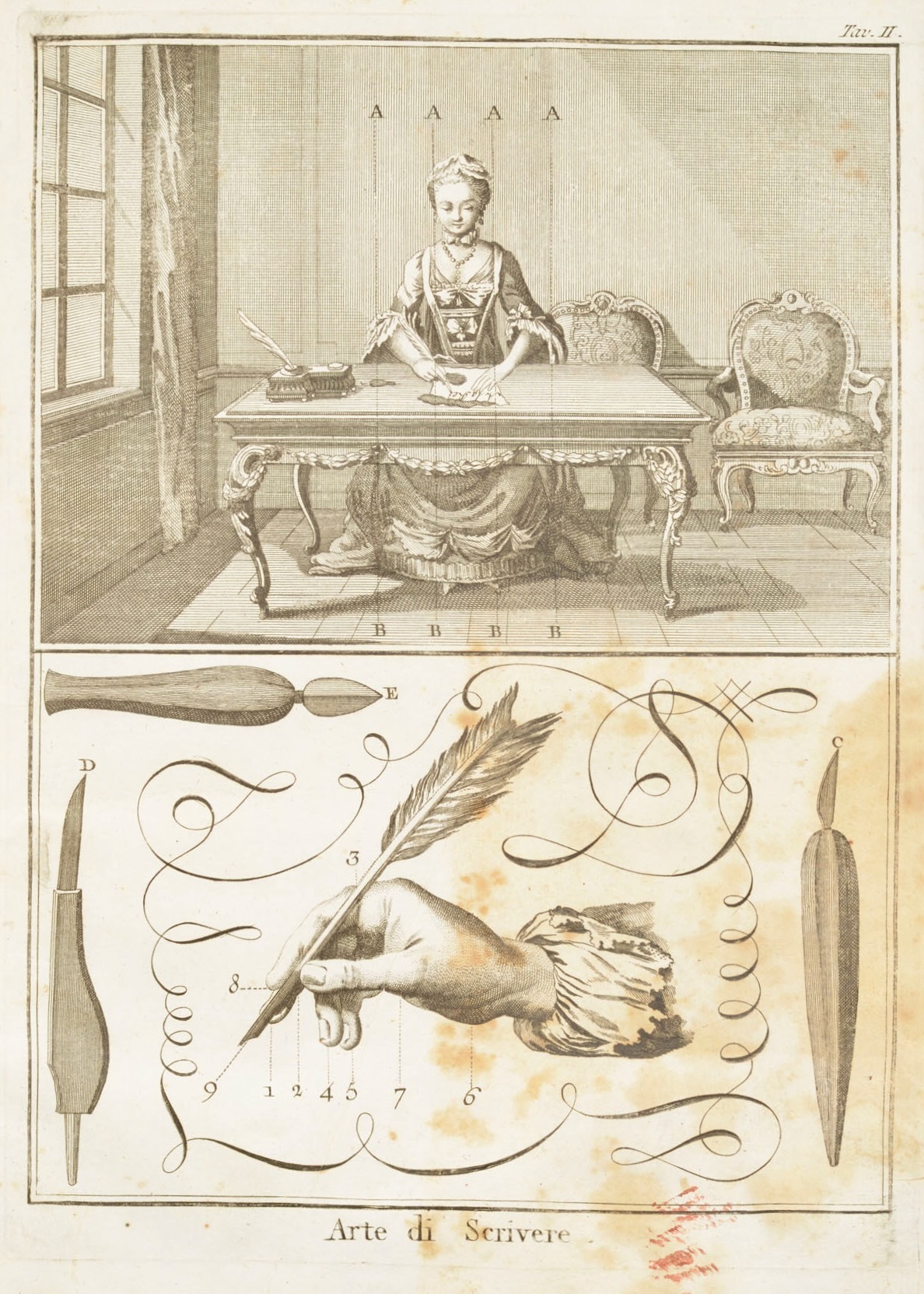

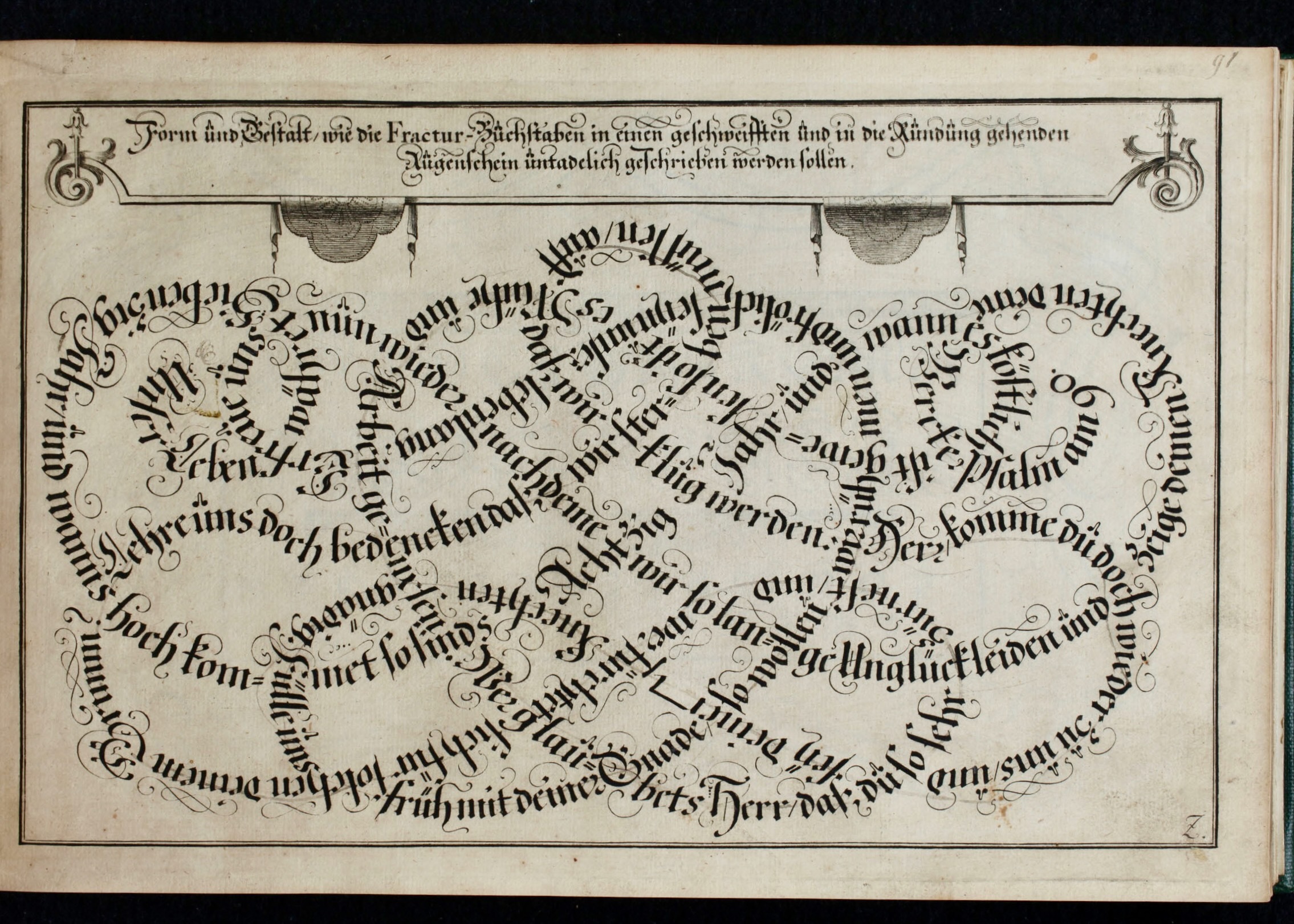

The writing manuals range from the most practical instructions to theoretical explanations of letter shapes. In two 16th-century manuals, the reader is given depictions and descriptions of the basic writing tools, including a quill, compass, pen knife, and an inkwell. Many manuals include recipes for making ink, instructions for cutting a quill, and descriptions of different shapes one could cut the tip of the quill.

Proper Posture

Once the tools, inks, and paper or parchment are ready, it’s time to pay attention to how to hold the pen. One recommended method is to use your first two fingers and thumb. Avoid clenching your fingers, as can be seen in the bottom illustration on a plate from AARB 00276. Note, too, that writing is a two-handed activity, so do not simply use your non-dominant hand to hold your coffee!

And of course, posture is everything! Be positioned to copy for hours at a time—shown here with adequate lighting, at a spacious table in a large room.

Practice and Results

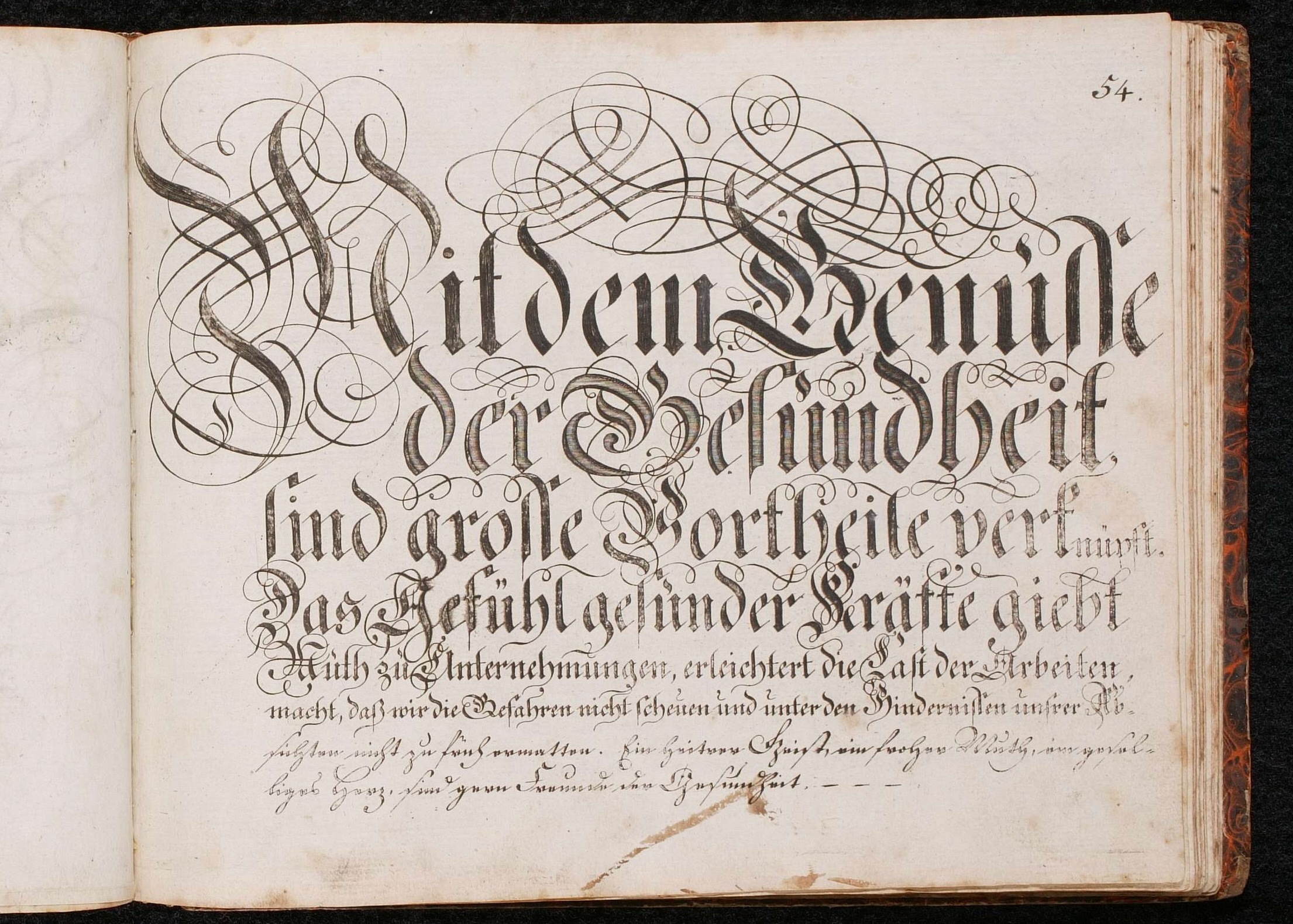

The scribe-in-training will want to imitate the many examples provided in the manuals, before attempting grander, more ornate decoration of their text.

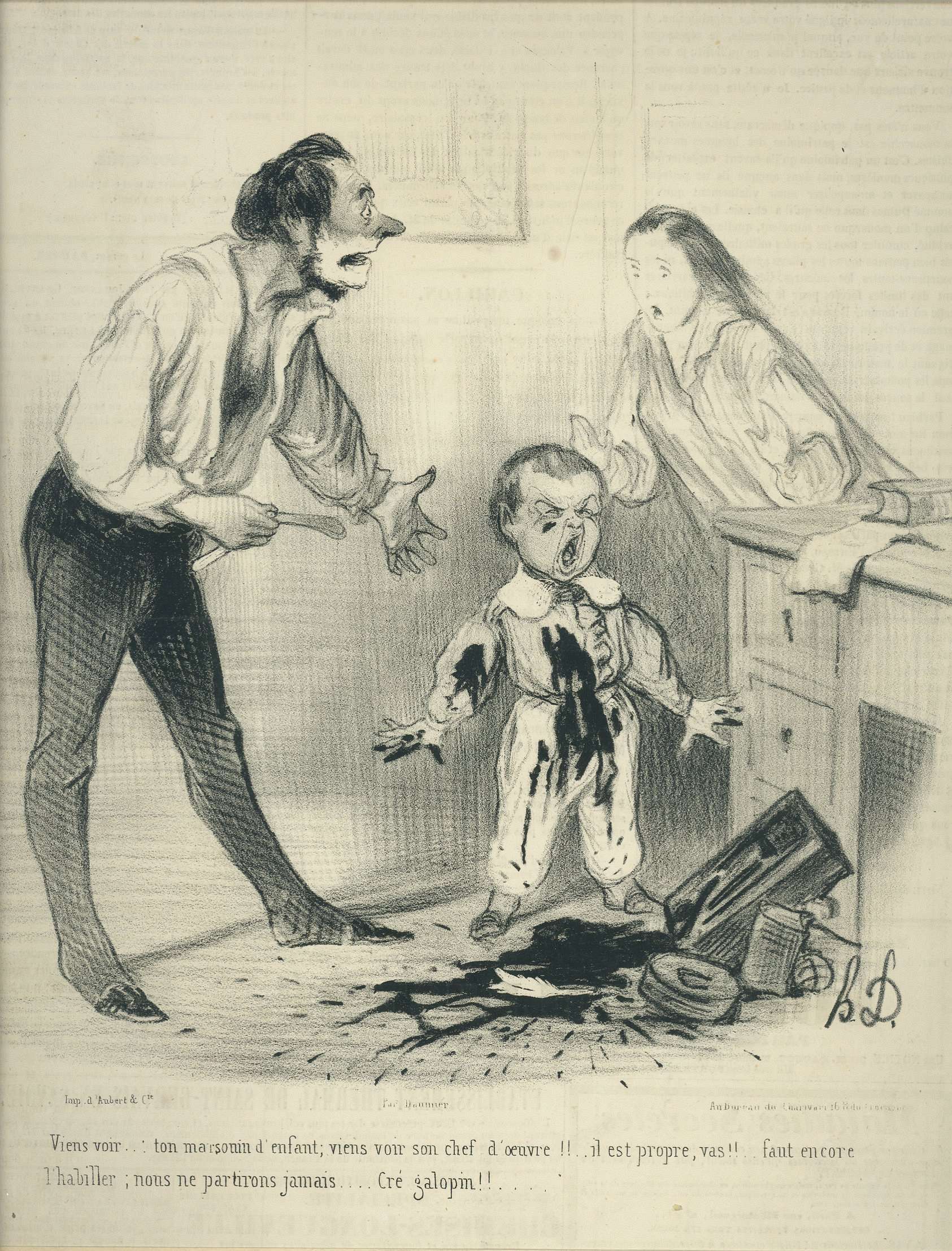

To be sure, it takes much practice and patience to become a good scribe or calligrapher. However, accidents do happen now and again.

There is much more for your scribal journey in the Western European collections in HMML Reading Room, including calligraphic books (AARB 00225) and writing and paleographical manuals from across Europe. Try, for example books printed in:

- Leipzig, Germany (AARB 00298)

- Italy—Florence (AARB 00149), Rome (AARB 00284), and Venice (AARB 00157)

- Madrid (AARB 00155, AARB 00293, AARB 00300)

- France—Paris (AARB 00156, AARB 00286, AARB 00291) and Mulhouse (AARB 00299)

- And numerous examples from London (AARB 00148, AARB 00161, AARB 00287, AARB 00295, AARB 00297).