Build A Church, Build A Library

Build a Church, Build a Library

This story is part of an ongoing series of editorials in which HMML curators and catalogers examine how specific themes appear across HMML’s digital collections. From the Eastern Christian collection, Dr. Josh Mugler shares this story about Scribes.

If you want to establish a new church, you’re likely going to need some books. Liturgical, biblical, and theological books have been important parts of most church collections. Before the era of widespread access to printed books, this meant that most churches needed someone to write their books by hand, and for many early Syriac Catholics in 18th- and 19th-century Mosul, Iraq, that person was named Ibrāhīm ibn Khidr.

We do not know much about Ibrāhīm’s early life. He was a native of the town of ʻAqrah in northern Iraq. In 1775 CE, he was still living in his hometown when he copied a manuscript containing several texts, including a compendium of theological quotations gathered as evidence against Catholic doctrines (MGMT 00190). However, when he moved to the larger city of Mosul, it seems that he began to run with a different crowd.

While Ibrāhīm was in Mosul, around 1783 CE, a group broke from the Syriac Orthodox patriarch to create a new Church in union with the pope in Rome. This Syriac Catholic Church maintained much of its ancient liturgy while also creating ties with the Catholic missionaries and merchants who had long traveled the region. In need of books to serve their new congregation in Mosul, the local leaders of this group turned to the deacon (and later priest) Ibrāhīm ibn Khidr.

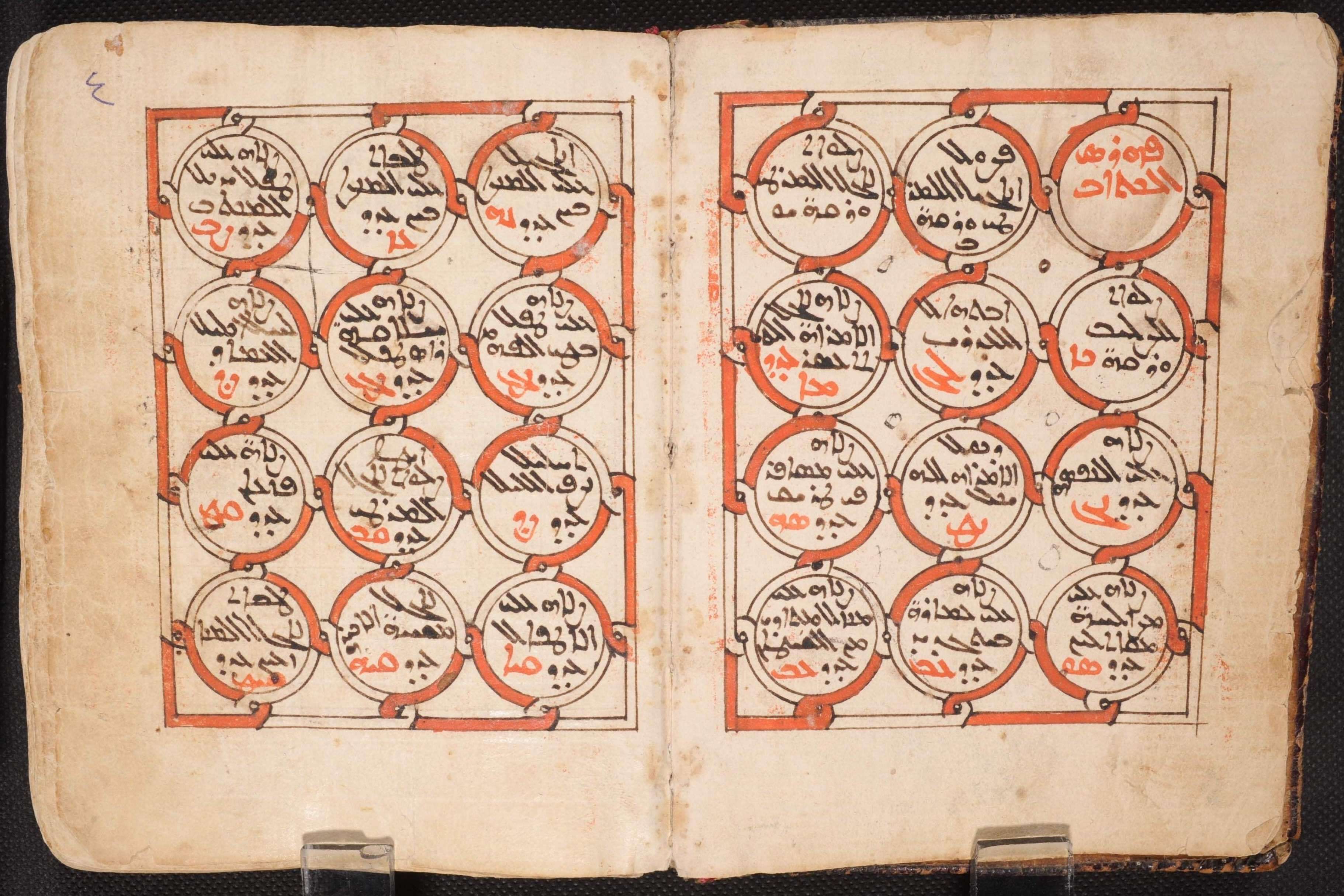

HMML’s collections contain no less than 27 manuscripts copied by Ibrāhīm. His detailed colophons include valuable information about the patrons who funded his work, often financially stable lay men and women who wanted to invest in the new Church. Some were likely part of the same trade networks that reached Syria and Europe and helped to bring Catholicism to the region.

Ibrāhīm copied a full suite of liturgical books for the various seasons, celebrations, and rituals of the Church. The vast majority were written for the church in the center of Mosul’s Citadel (al-Qalʻah) district, dedicated to the Virgin Mary al-Ṭāhirah (“the Immaculate,” one of several Mosul churches by that name). In 1792 CE, Ibrāhīm also copied a prayer book for his own use as a priest, choosing to include prayers that his congregation might request for such important occasions as the construction of a new house and a child getting a haircut (MBM 00400).

Most of Ibrāhīm’s known manuscripts remain in the Mosul area. At least eight are still at the church for which they were copied: Kanīsat al-Ṭāhirah al-Dākhilīyah (al-Qalʻah). This church has gone through lengthy property struggles over the centuries, and their manuscript collection now belongs to the Syriac Orthodox Church. In 1914 CE, a local Orthodox priest made repairs to a book of funeral liturgies copied by Ibrāhīm in 1810 CE, demonstrating that his manuscripts have remained useful no matter the church’s sectarian affiliation (SOCTQM 00053, fol. 193r).

Many other manuscripts copied by Ibrāhīm have moved outside the city to the Syriac Catholic monastery of Mar Behnam. His early anti-Catholic manuscript, on the other hand, is at the Syriac Orthodox monastery of Mor Gabriel in Mardin, Turkey. At least one of his manuscripts has left the region altogether, finding its way to Montserrat Abbey near Barcelona, Spain (microfilm 30225).

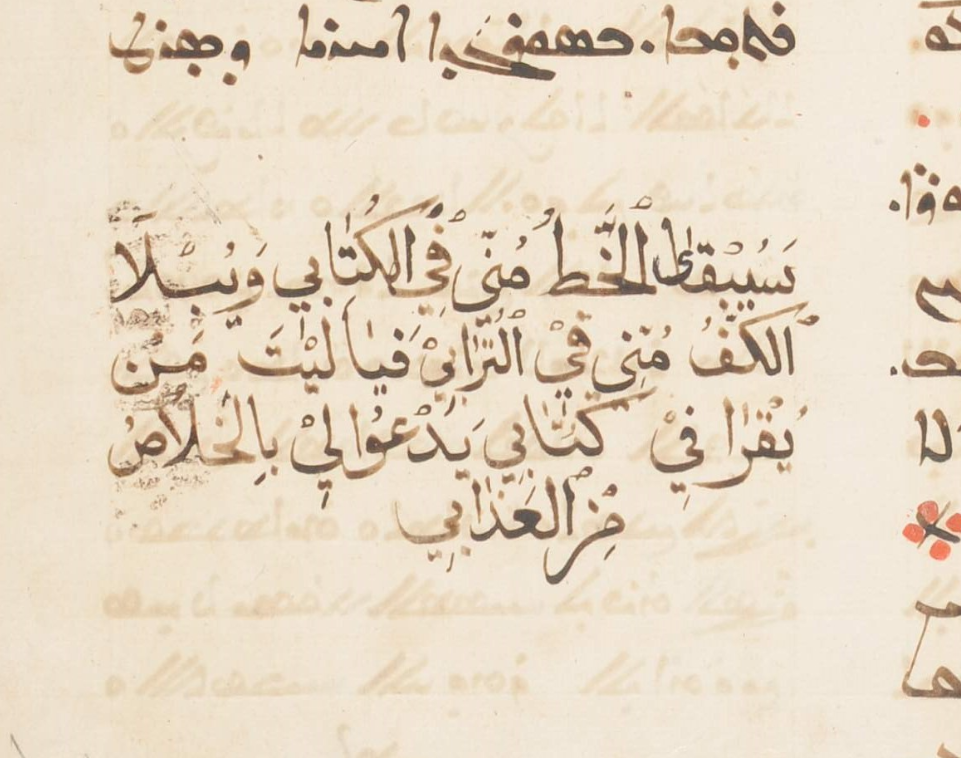

Ibrāhīm’s latest known manuscripts were copied in 1810 CE, so he may have died not long after that date. Several of his colophons include a poem in Arabic, which was not authored by Ibrāhīm but which he seems to have found meaningful. The poem reflects on the inevitability of his own death and the fact that his manuscripts will long outlive him—the very reason that we are able to learn about Ibrāhīm today:

My handwriting will endure in the book

When my hand is rotting in the dirt.

So may the one who reads my book

Pray for my salvation from punishment.

(SOCTQM 00007, fol. 194r)