Music Awakens One’s Soul...

Music Awakens One’s Soul...

This story is part of an ongoing series of editorials in which HMML curators and catalogers examine how specific themes appear across HMML’s digital collections. On the theme of Music, Dr. Ani Shahinian has this story from the Eastern Christian collection.

Hymns in Armenian Christianity

An answer to the question of what it means to be human can be found in the Sharaknotsʻ (hymnal)—through the Armenian theological thought illustrated in a genre that is, almost entirely, canonical sharakans (hymns). For Armenian hymn-writers and theologians, music served as a bridge between divine and human communication after the expulsion from the Garden of Eden. Just as light surrounded the human being in the Garden, so music surrounds the human soul to give an inkling of divine grace.

While there are other collections of church hymns, melodies, and songs in the Gandzaran (the collection of litanies) and Tagharan (the collection of hymnic odes), the Sharaknots‘ uniquely incorporates an eight-mode chant-system—interwoven with the Prophets, Psalms, and Gospels—to show an unfolding human engagement with the divine throughout the daily, weekly, and yearly cycles.

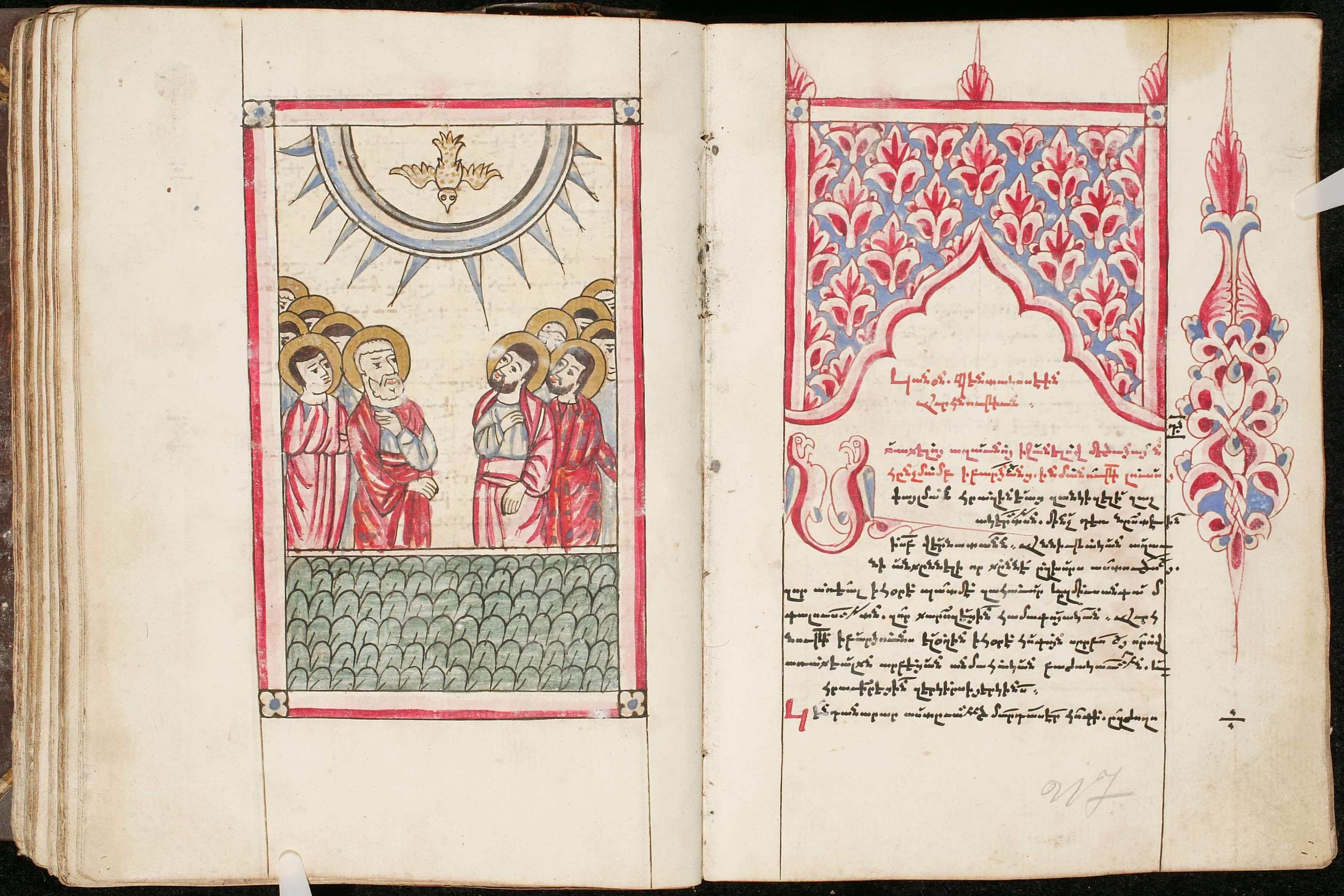

The Armenian manuscript collection at HMML—photographs of manuscripts located in Iraq, Lebanon, Syria, and Turkey, dating from the 13th to 20th centuries, with at least 80 hymnals, hymns, and musical notations identified so far—reflects the importance and the role the Sharaknots‘ had in Armenian church culture, as observed in the number of copies it circulated widely throughout the millennia.

Catholicos Karekin I (1932–1999), in a detailed study on the sharakans, showed that while sharakans have value in the various disciplines of literature, history, theology, etc., they are primarily prayers, expressing the depths of the human soul to the divine. The music bridges a person’s mind, body, and soul through vibrations and the timbre of voice, giving shape and form to the invisible expression of human emotion and rationality.

Authors of the Hymns

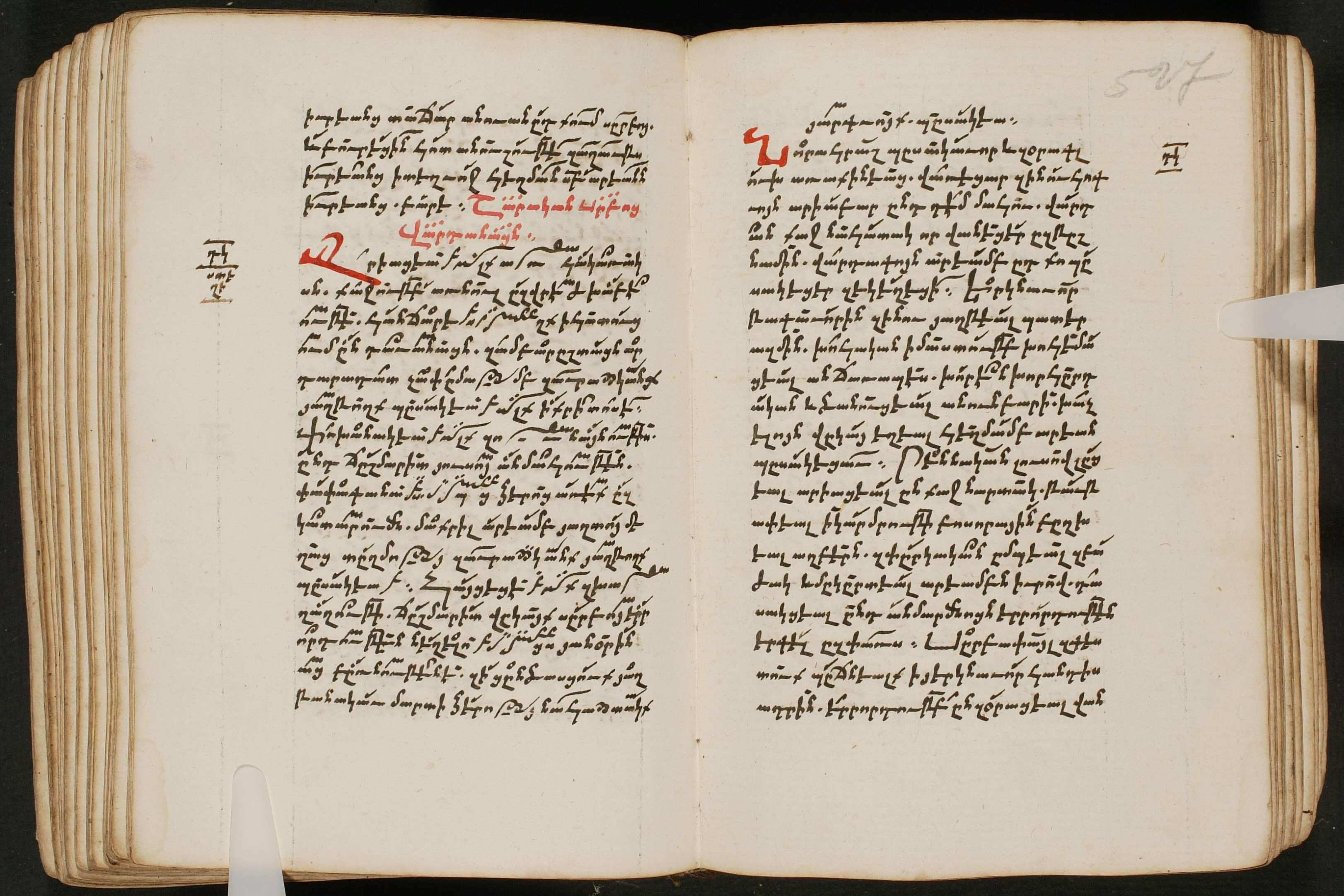

The Sharaknots‘ has an extensive history of compilation and editions, with the earliest sharakans dating back to the 5th century. Nersēs Shnorhali (1102–1173 CE), also known as Nersēs the Graceful, is part of a long list of vardapets (church fathers/teachers) in Armenian ecclesial history who contributed to the enrichment of the Sharaknots‘.

Shnorhali was the Catholicos in Cilicia from 1166 to 1173 CE and a remarkable theologian of his time, striving to bring harmony to the Church after the schism that took place between the East and West in 1054 CE. He was also a poet and hymnographer (hymn writer) who composed his works in ways that communicated to the hearts and minds of diverse audiences. Shnorhali remains an exemplary figure even today. In 2023, ecclesial communities around the world celebrated Shnorhali’s 850th anniversary, highlighting his contributions in the various disciplines, including hymnography.

In his sharakans Shnorhali reflected on Genesis 1:27, weaving in the concept that human beings, created in the image and likeness of God, are placed as lights in the world. A novel contribution of Shnorhali was his addition of sharakans for particular saints—lights in their own contexts—a tradition that continued after him.

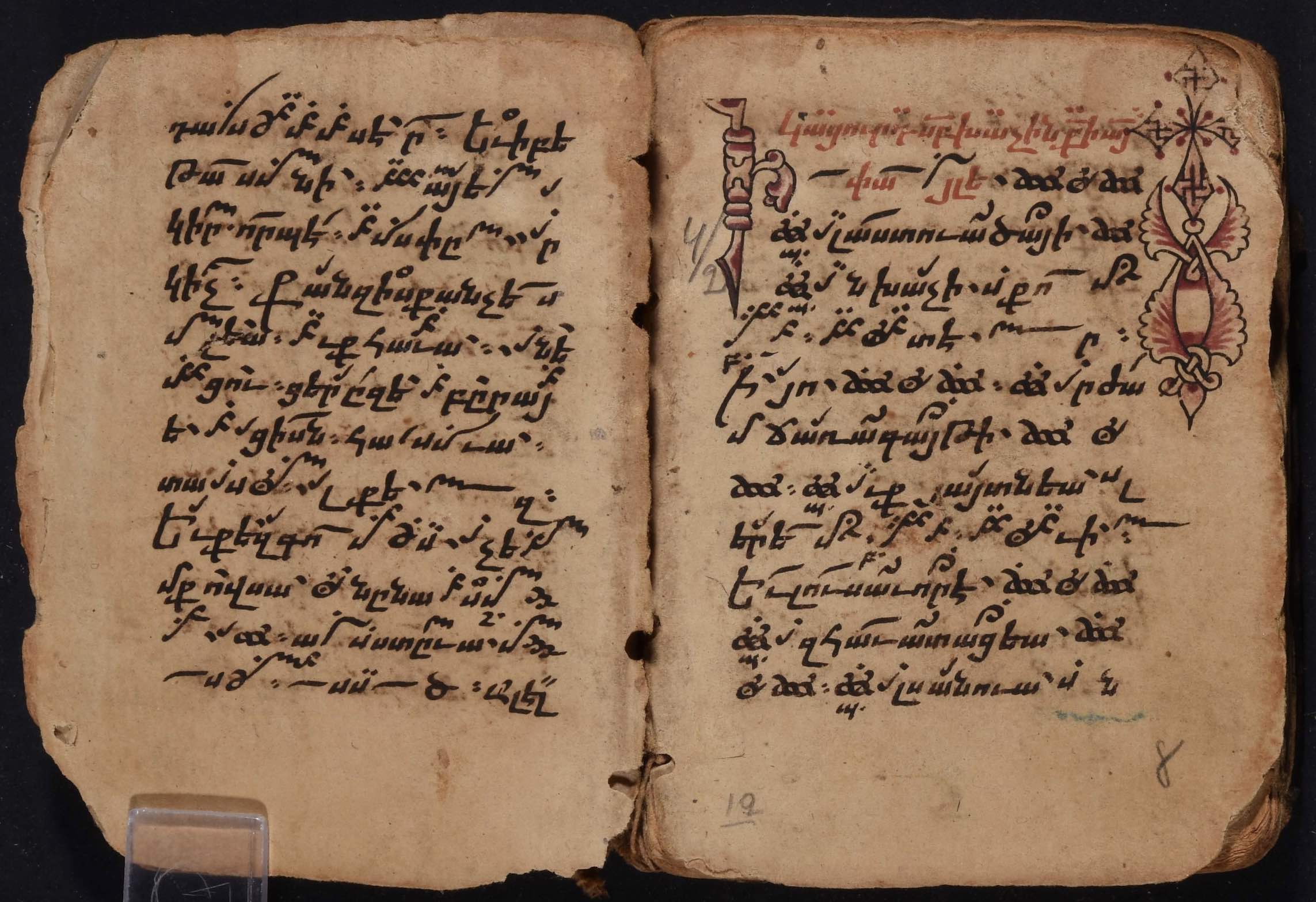

Sharakans written by and attributed to Shnorhali were incorporated into the Sharaknots‘ gradually. The oldest codices do not always include his works, but by the 14th century, we begin to find Shnorhali’s hymns integrated into the Sharaknots‘. One manuscript in the collection of the Armenian Patriarchate of Istanbul (APIA 00164) contains a sharakan by Shnorhali, written for the martyrs of Vardanants‘.

Students of the Melodies

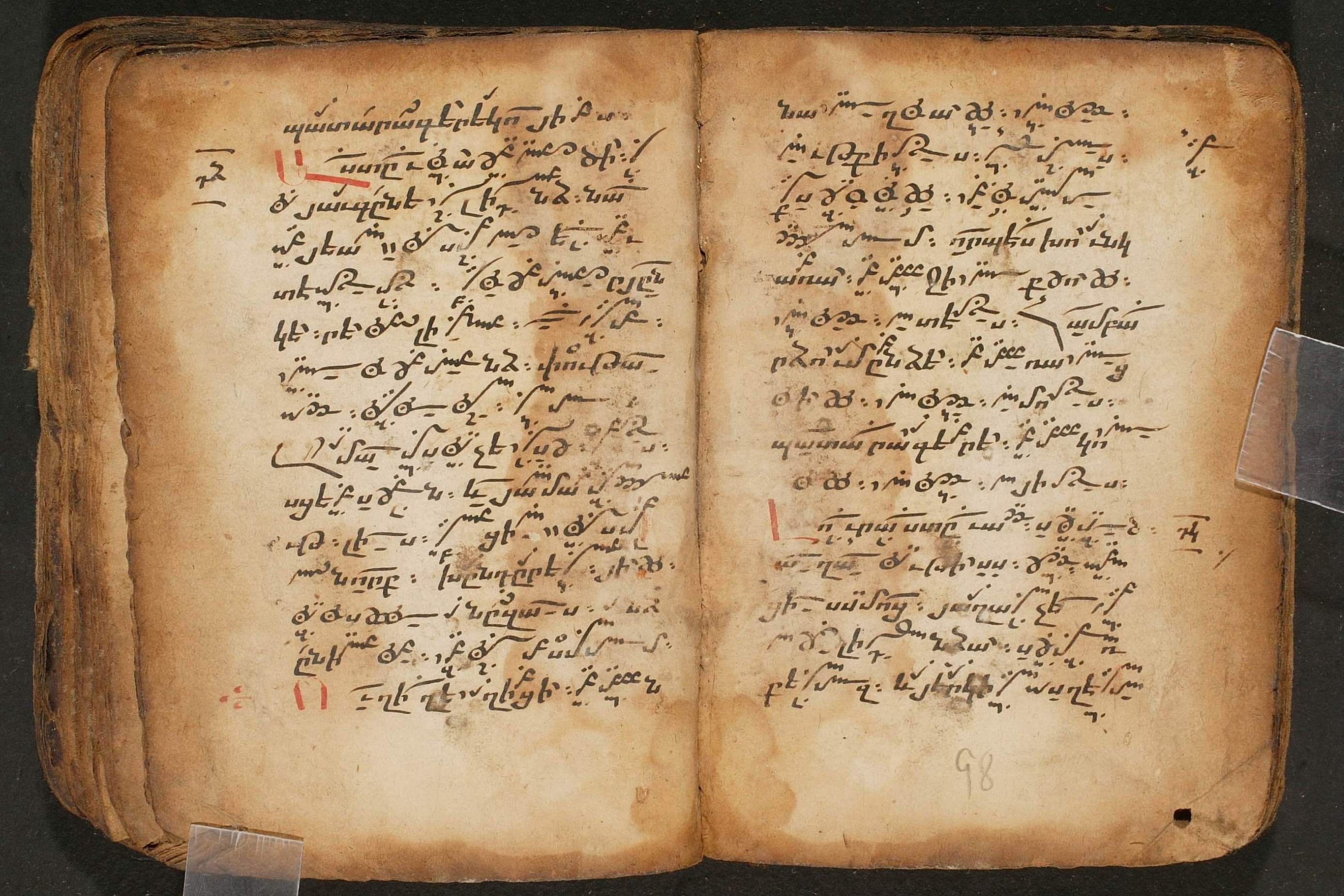

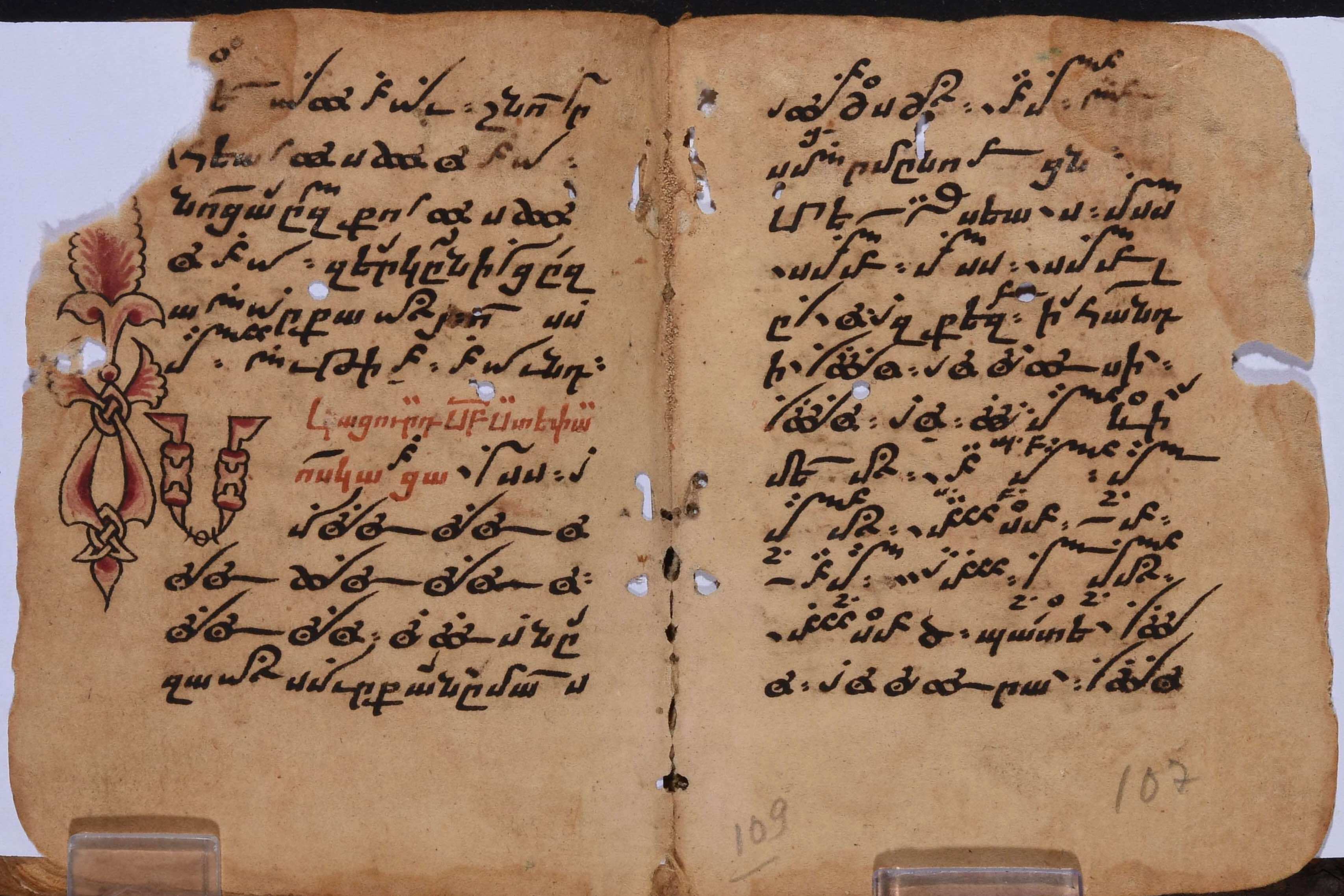

Today, the musical notations known as khaz—used in different types of hymnals in the Armenian tradition, including the Sharaknots‘—are a mystery. Over time, church musicians lost the ability to read the khaz neumes and, consequently, we are unable to reconstruct the original melodies.

This mystery, however, did not stop musicians. The neumes continued to be copied with attempts to reproduce them in new contexts. In the 19th century, we find examples of church musicians transcribing sharakans into different forms of musical notations.

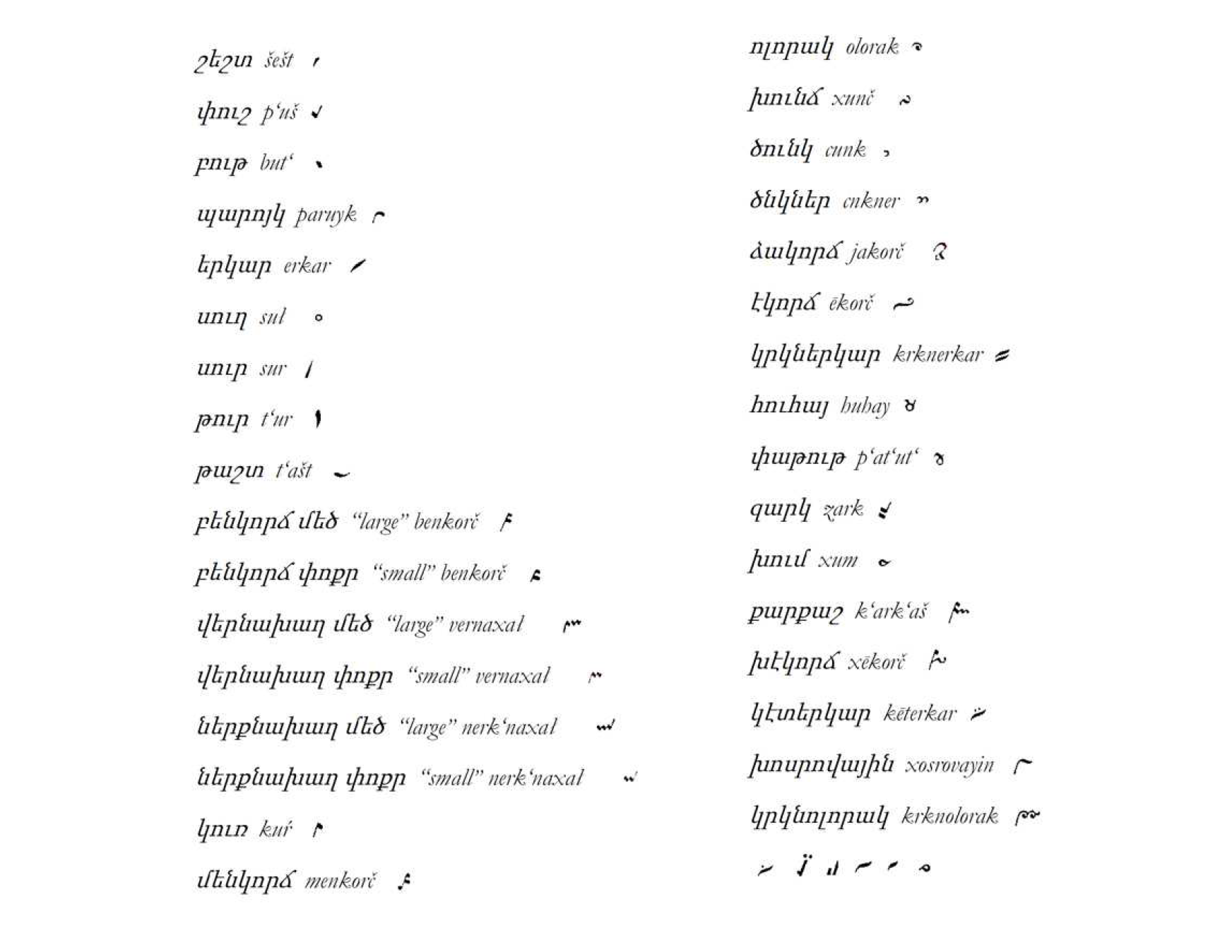

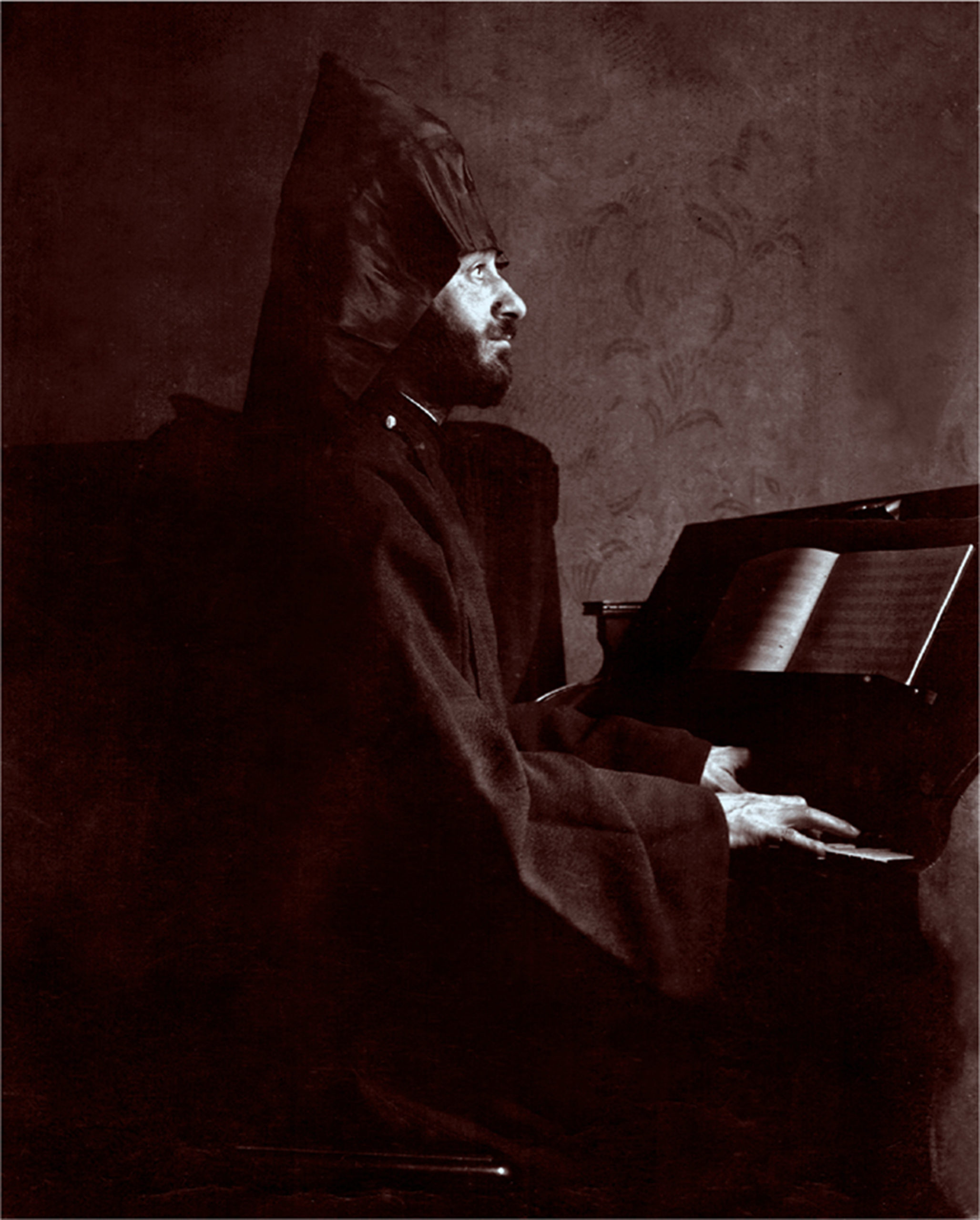

Soghomon Soghomonian (1869–1935), also known as Komitas Vardapet, was a significant contributor to Armenian music in 19th and 20th centuries. He wrote about the musical notations of Armenian hymnals and listed a substantial number of neumes—identifying 198 types of khazs. In his great effort, he recognized that many more khazs remain unidentified. Although Komitas identified the neumes, his study remained incomplete at the onset of the Armenian Genocide in the Ottoman Empire.

An example of khaz notation can be seen in a fascinating K‘ats‘urdatan manuscript, photographed by HMML in Lebanon. K‘ats‘urds are another genre altogether, and one that became obsolete after the first few centuries of composing hymns and psalmodies (singing of the Psalms) in Armenian. K‘ats‘urds are highly specialized festal hymns. This beautiful copy of K‘ats‘urdatan displays treasure buried in mystery—unknown melodies of khazs, which remain a subject for scholars to unearth.

Further Reading:

Karekin I. Hay ekełec‘woy astuacabanut’iwnǝ ǝst hay šarakanneru (The Theology of the Armenian Church According to the Armenian Sharakans), vardapetakan čaṙ, Lebanon: Ant‘ilias (2003).

Abraham Terian. “To Byzantium with Love: The Overtures of Saint Nerses the Gracious,” in Armenian Cilicia, volume 7 in the series Historic Armenian Cities and Provinces, edited by Richard G. Hovannisian (Costa Mesa, 2008), Chapter 7, pages 131–151.

Haig Utidjian. “A Brief Survey of Systems of Musical Notation in Armenian Sacred Music,” in Reflections on Armenia and the Christian Orient: Studies in Honour of Vrej Nersessian (Christiane Esche-Ramshorn, ed.), 2017.

Nersessian Vrej. Essays on Armenian Music. Kahn & Averill for the Institute of Armenian Music. London, England (1978).