A Christmas Hymn Sing Along

A Christmas Hymn Sing-Along

This story is part of an ongoing series of editorials in which HMML curators and catalogers examine how specific themes appear across HMML’s digital collections. On the theme of Music, Dr. Catherine Walsh has this story from HMML's Special collections.

Singing is one of those amazing things. It’s universal—nearly all people sing, across borders of time, place, culture, and religion—yet singing is also so culturally situated. We sing songs that matter to us, in settings that change as our world changes. Today, that might mean many things: crooning a lullaby to soothe a restless child, singing on a stage to crowds, belting out your favorite song alone in your car, adding your solo to a duet-chain video online, or raising your voice with others in celebration, sorrow, or protest.

In 1926, a group of artisans and artists, known as the Guild of St. Joseph and St. Dominic, decided to rethink what singing meant to them.

The Guild

They had already made a lot of changes. After the chaos of World War I, these Roman Catholic artists and artisans moved to Ditchling, a small village in East Sussex, England. There, they sought meaning in community, underpinned by a belief in small ownership and the notion that craft was an important part of a life based on faith and cooperation.

Modeled after medieval guilds and influenced by monastic communities, the guild and its workshops thrived for decades, from its founding in 1921 until it closed in 1989. As the community grew and established ties with the Dominican Third Order (a Roman Catholic lay religious order) they were joined by artists of many types—weavers, carpenters, stone carvers, wood engravers, silversmiths, and poets. And from the first, they had their own private printing operation.

The Press

St. Dominic’s Press was established in 1916 by Hilary Pepler, a printer with a credo. He was interested in the Arts and Crafts movement, but he wanted to print books for use rather than for collectors—making things that were “good and didn’t know it.” Books should be handmade, but simple. Printing was mostly done using hand presses, with handset type, on handmade paper, and with hand-carved wood engravings.

The Book

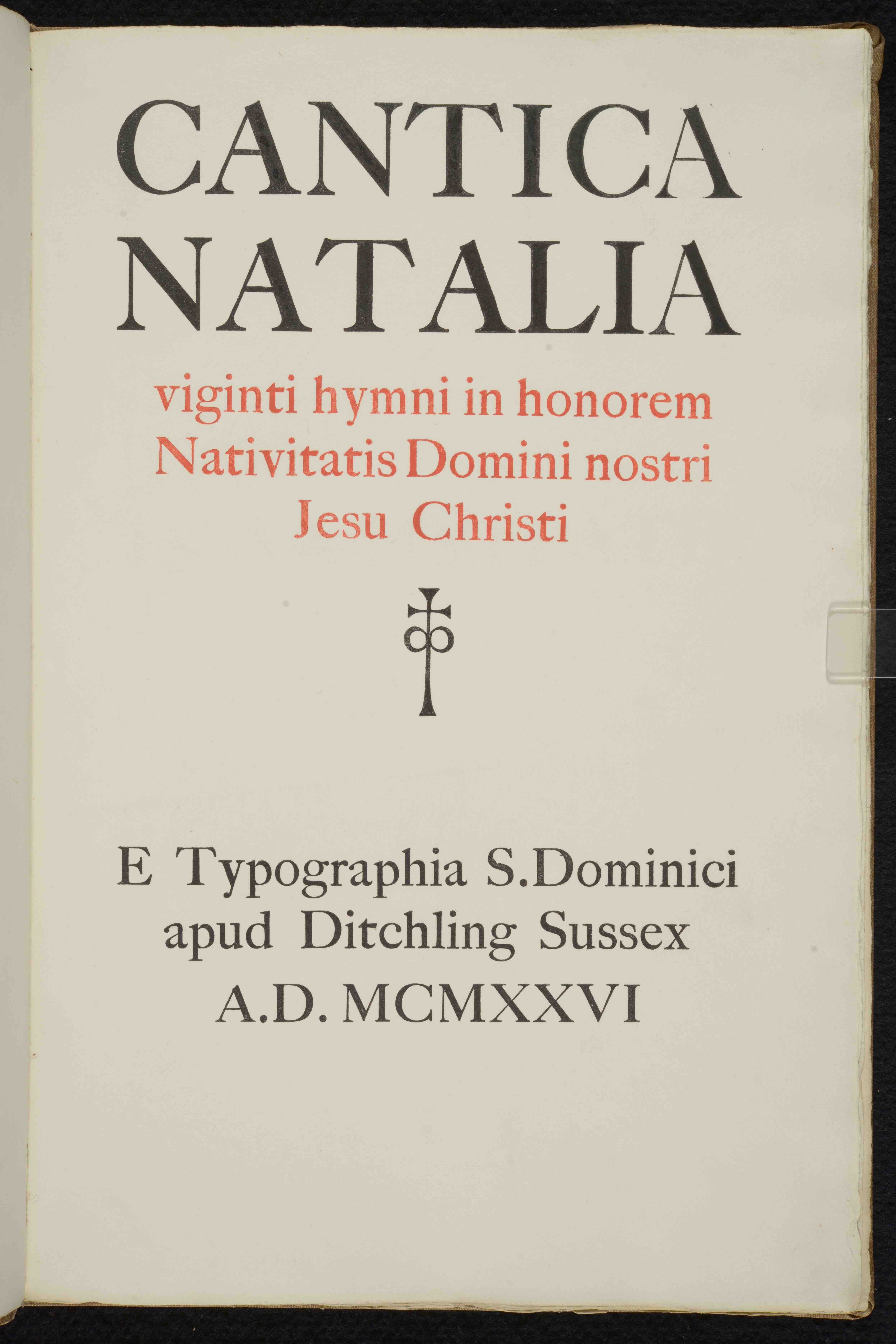

Cantica Natalia, published by St. Dominic’s in 1926, contains 20 Christmas hymns, and it illustrates many of the principles that informed the artisans, guild, and press that produced it.

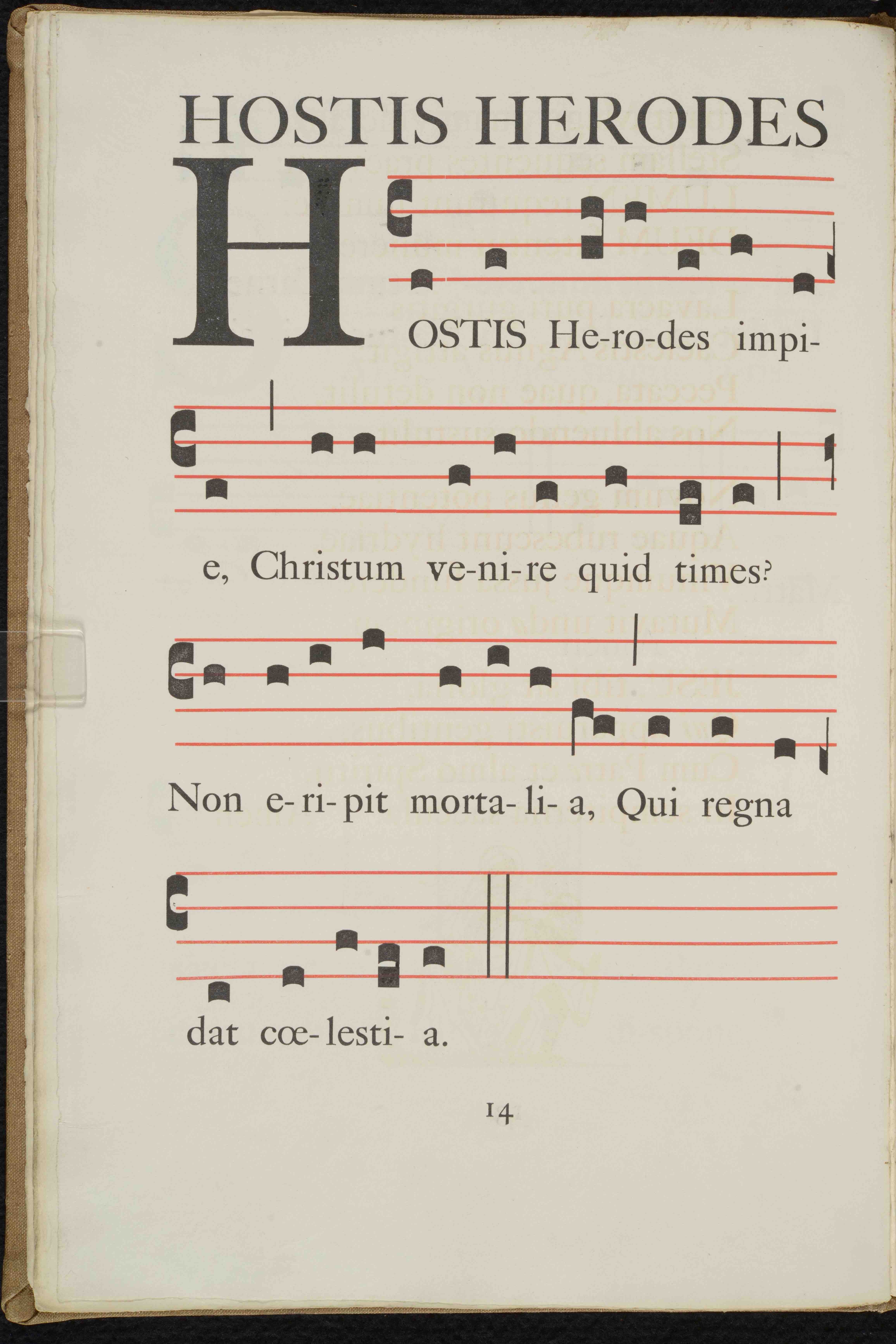

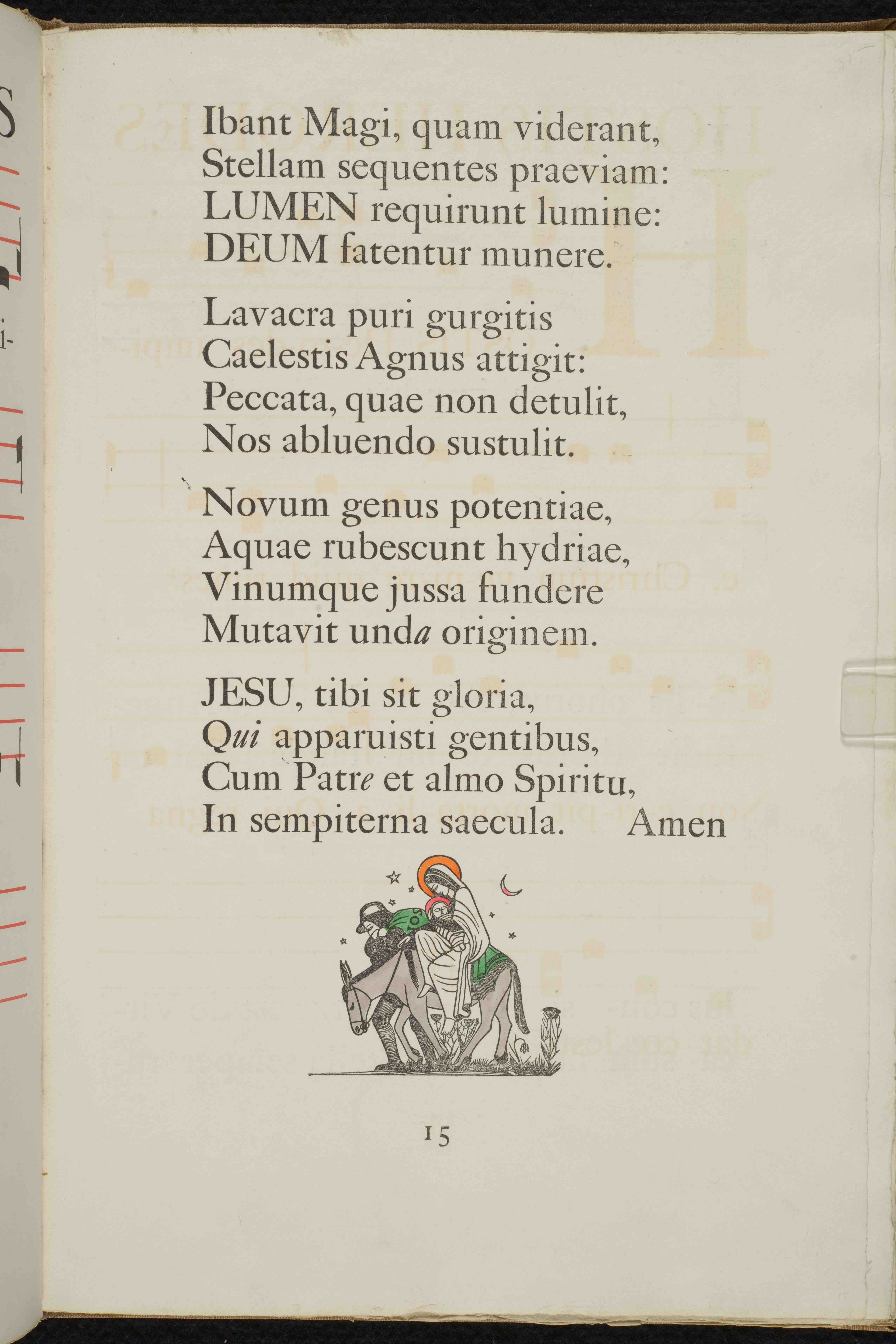

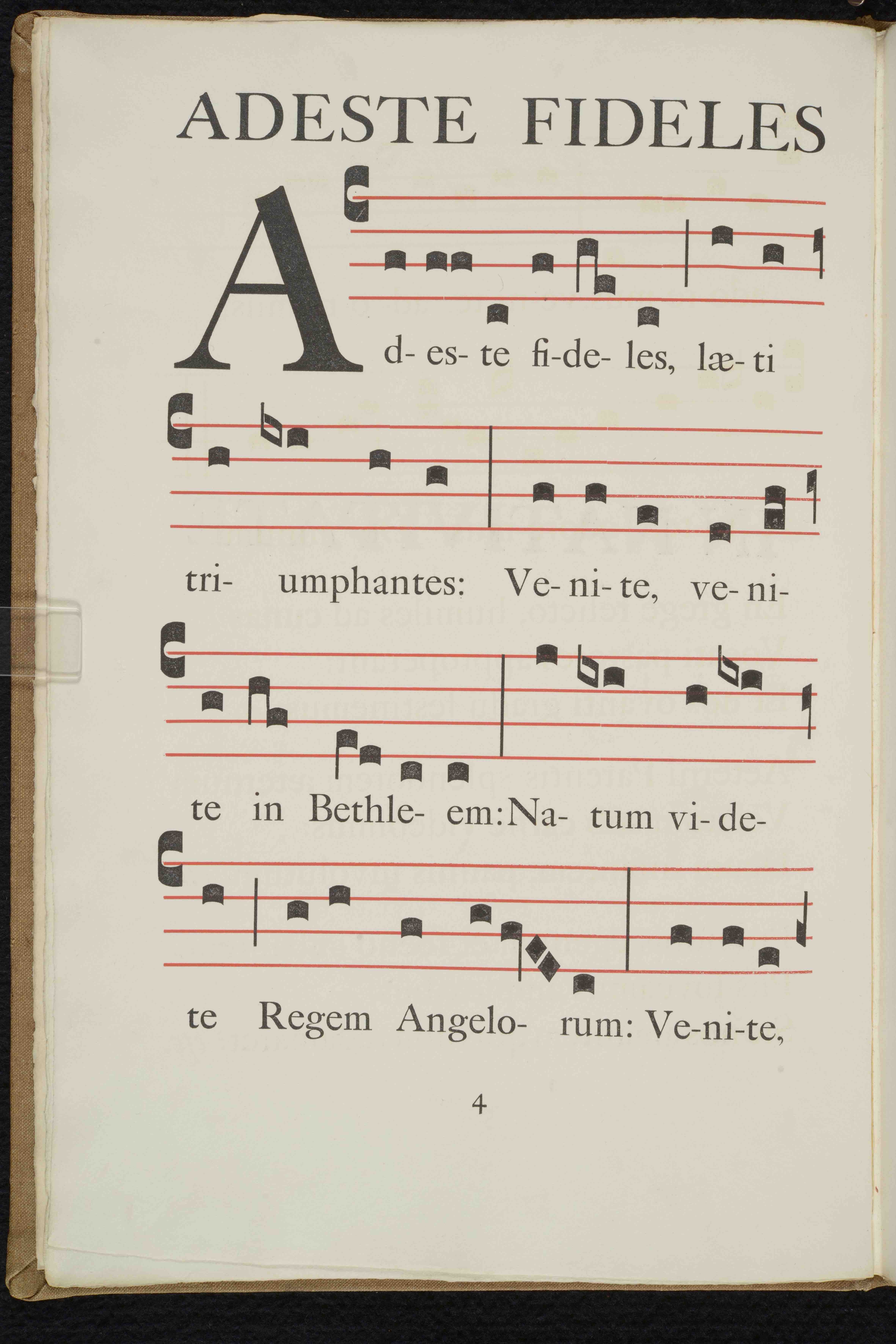

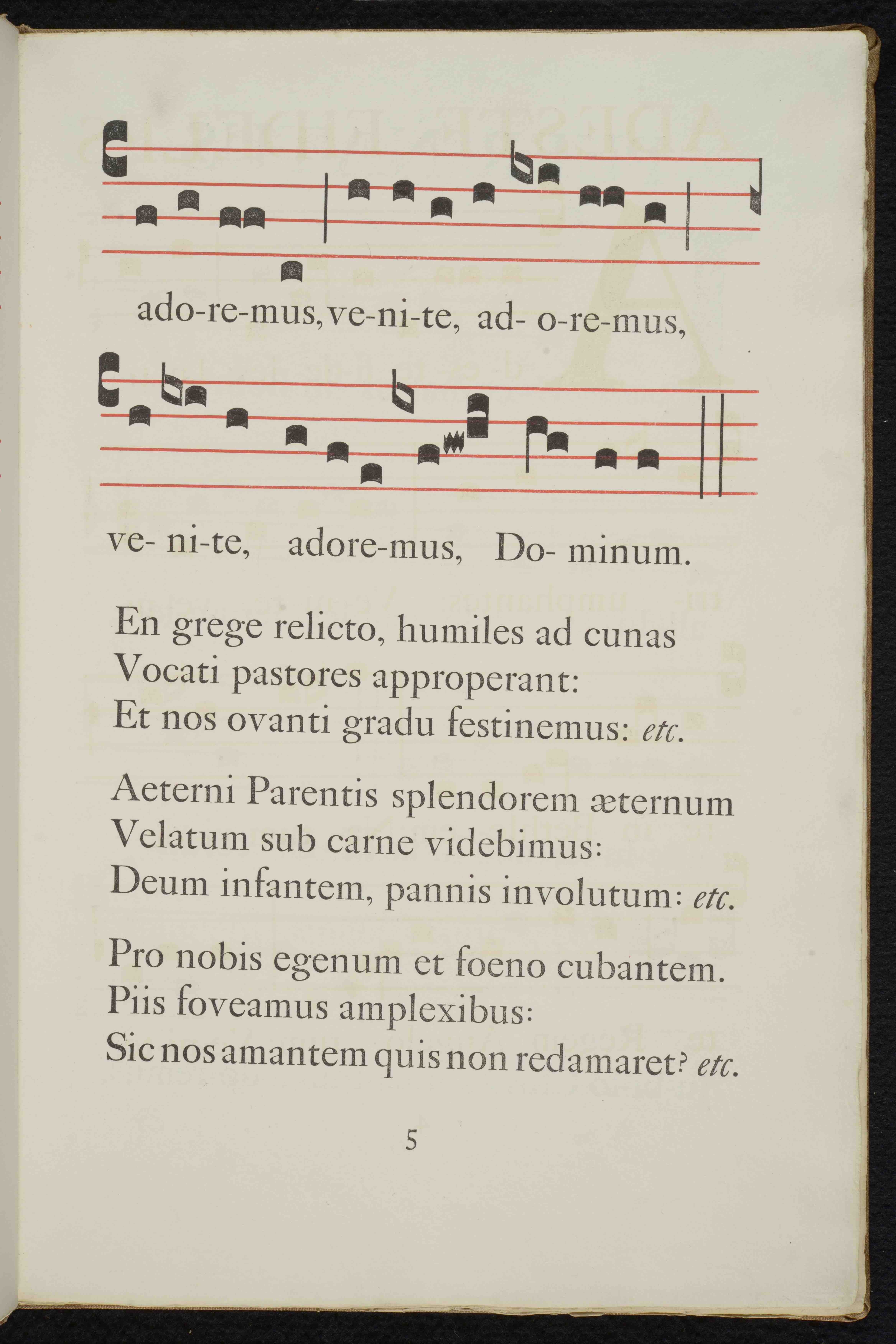

The book is large and sumptuous, yet its pages showcase a simple, modern design and layout. It is printed, but the emphasis is on handwork that harkens back to manuscripts, including hand-colored wood engravings. It contains traditional Christmas carols like “Adeste Fideles” (best known by current audiences, perhaps, as “O Come All Ye Faithful”), but they are mostly in Latin, using plainchant notation and neumes (square notes) rather than the modern musical notation more familiar to choirs today. (Check out I Know It When I See It for more details on musical notation.)

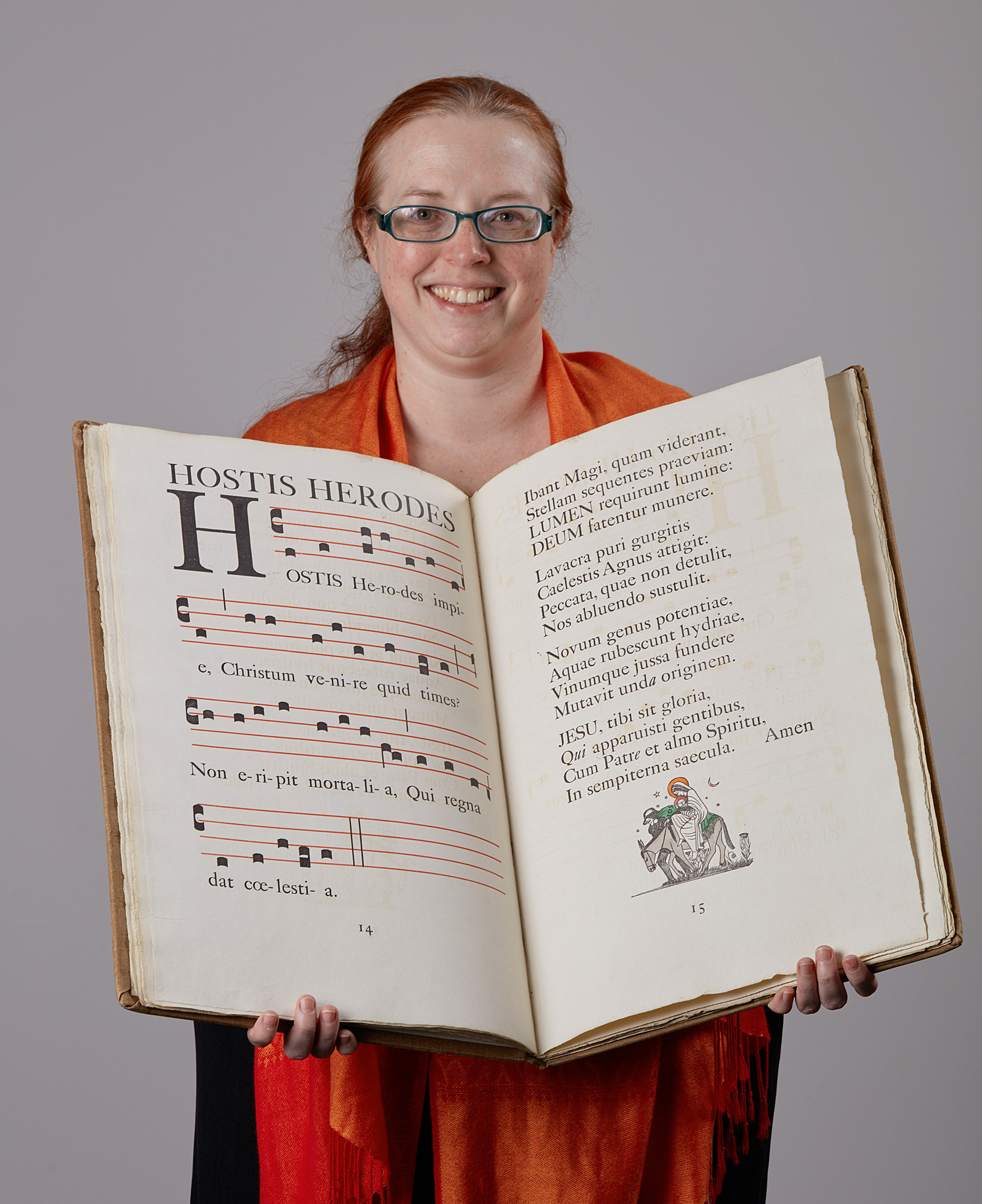

Cantica Natalia is beautiful (I encourage book lovers to spend time browsing its pages), and there is much to discuss, but today I want to focus on something not readily visible when viewing digital images of the pages.

This book is huge. Why?

Singing Together

Made by crafters that value community, Cantica Natalia was designed with its purpose in mind: this singing was meant to be done together. Traditional hymnals are made to be held in a single person’s hands. This large book, with a height of 51 centimeters, was instead meant to sit upon a lectern while many people gathered around it. The 36-point type is large enough to read at a distance. As one printer’s diary reveals, the book was made partly for use by the choir of St. Wilfrid’s Burgess Hill, a parish church in a nearby village, “so that they could sing with their heads up and not in their books.”

Plainchant is meant to be sung by many voices, just as the book was made by many hands (four artists contributed to the 12 wood engravings, not to mention the printers and typesetters involved). Imagine how it changes the physicality of the singing experience not only to sing up—rather than down—but also to have the entire choir gathered shoulder to shoulder, standing closely together before a single large book.

You too can join this community. Even if you don’t read plainchant notation (I do not!), see if you can follow along with the pages of “Adeste Fideles” from Cantica Natalia, as you listen to it.

The line of the melody ascends and descends, like the neumes move up and down on the staff. Lines through the staff signal breaths, and attached neumes indicate where two notes are sung on a single syllable (e.g., the “de” in “fideles”). The version sung by the Benedictine monks of Santo Domingo de Silos is very similar to that depicted in Cantica Natalia!

Further Reading:

Hilary Pepler and the Saint Dominic’s Press, The Aylesford Review 7, no. 1 (Spring 1965).

Michael Taylor and Brocard Sewell, Saint Dominic's Press: A Bibliography, 1916-1937 (Lower Marston, England: The Whittington Press, 1995).

Noel Jones, A Beginner’s Guide to Reading Gregorian Chant Notation (Frog Music Press, 2008).