To Timbuktu From A Land Far Away: Migrating Manuscripts

To Timbuktu From a Land Far Away: Migrating Manuscripts

This story is part of an ongoing series of editorials in which HMML curators and catalogers examine how specific themes appear across HMML’s digital collections. From Islamic collection, Dr. Ali Diakite and Dr. Paul Naylor have this story about Migration.

Texts in West Africa were highly mobile, as we explained in our Editorial on travel. Here, we look at stories of migration through several manuscripts that came to Mali from even further afield, following more circuitous routes before finding a home in Timbuktu’s libraries. These findings reinstate the vision of West Africa as a connected, cosmopolitan region well before the advent of modern globalization.

As we catalog HMML’s Timbuktu collections photographed in Mali, we can tell which manuscripts originated from outside of West Africa due to the script, the design of the text on the page, the style of decorative elements that may be present, and even the size of the pages. Such imported manuscripts may have been brought back from pilgrimage to Mecca, purchased while traveling, or bought from merchants moving back and forth across the Sahara.

Sometimes, the route of a particular manuscript can be gleaned from the colophon or any accompanying provenance notes.

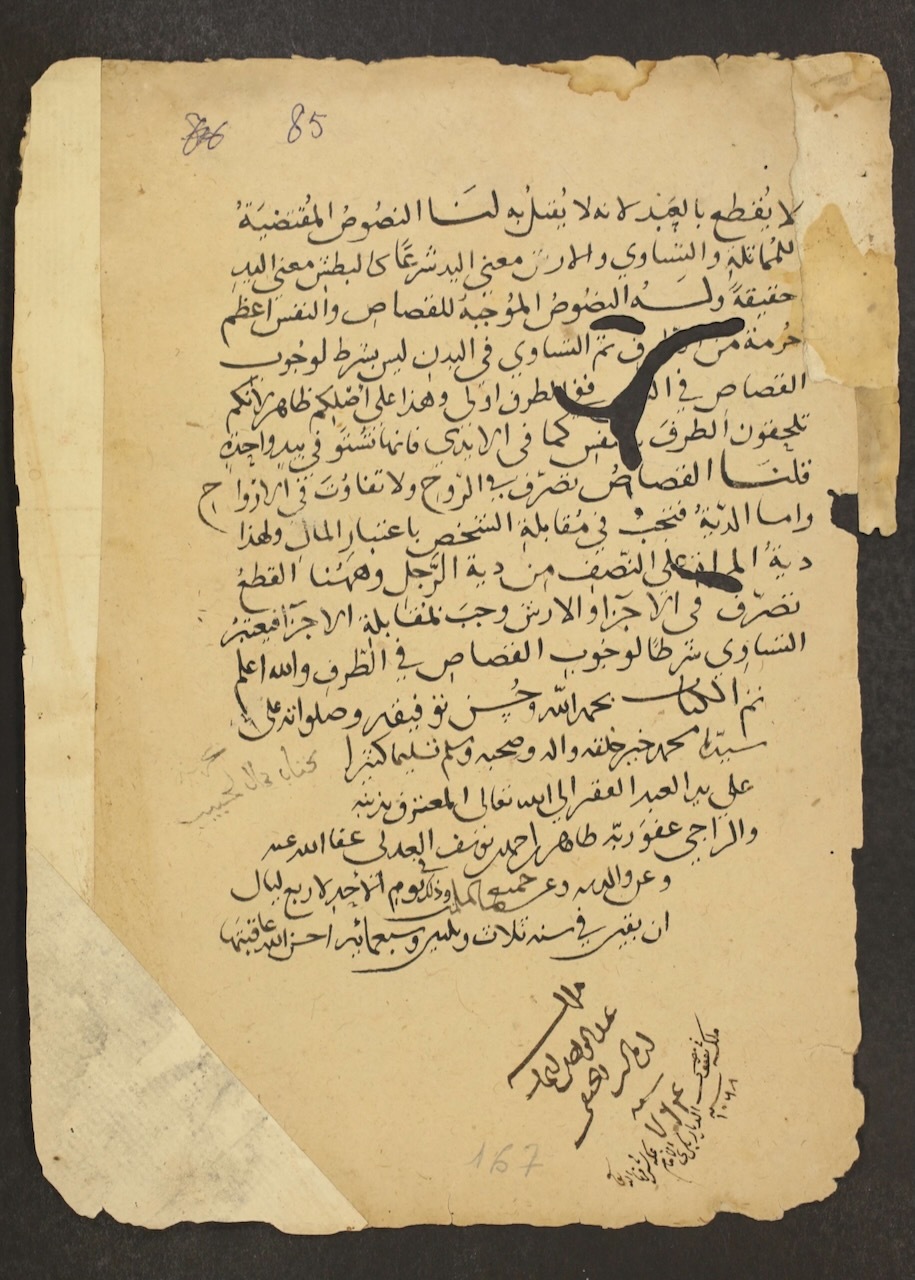

SAV BMH 35393, a manual of Hanafi law, has a particularly rich history of migration. The text, composed in the 13th century by Yūsuf ibn Qizughlī, popularly known as Sibṭ ibn al-Jawzī, was copied by Ṭāhir ibn Aḥmad ibn Yūsuf al-ʻAdlī barely 100 years later, on October 4, 1362 CE. The name strongly suggests that the copyist was Zaydī, a Shia minority living mainly in Yemen. In the following year, the manuscript was transferred to the ownership of ʻAbd al-Wahhāb al-Ḥanafī and, in 1657 or 1658 CE (1068 AH), to Yaʻqūb al-Diyārbakrī, who is described as being an imam of Mecca. How and when the manuscript found its way to Timbuktu after this period is a mystery.

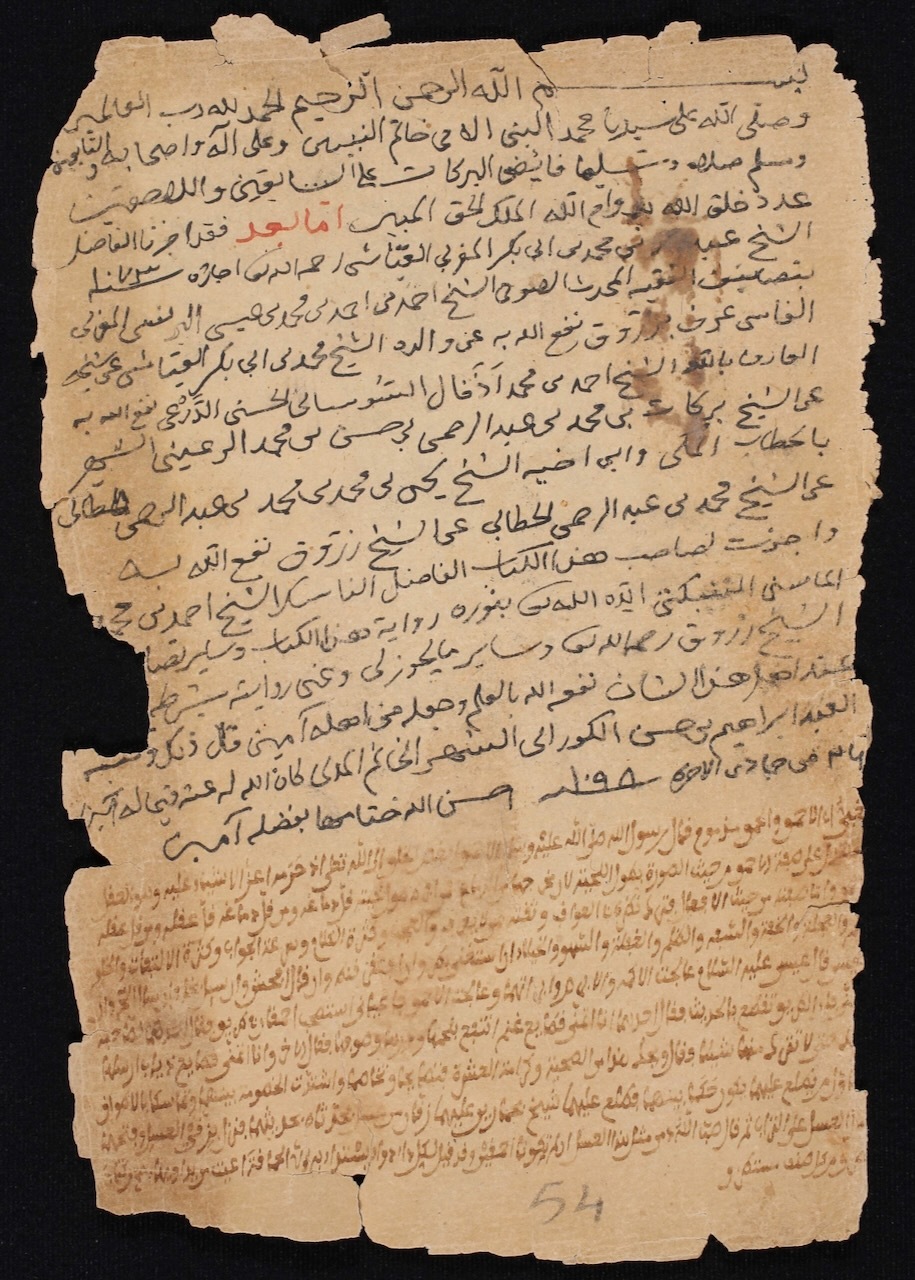

Meanwhile, SAV ABS 03135, a commentary by Aḥmad Zarrūq (–1493 CE) on Ibn ʻAskar’s legal treatise Irshād al-sālik, was copied in Medina in 1687 CE. Following the colophon, there is an ijāzah (teaching license for the book) stating that in the month after the manuscript was copied—specifically on May 9, 1687 CE—Ibrāhīm ibn Ḥaṣan al-Kūrānī, a prolific Naqshabandī author and teacher, taught the book to its owner, the pilgrim Aḥmad ibn Muḥammad al-Māsinī al-Tinbuktī.

Al-Kūrānī, who was himself a Kurd from the region of present-day Iraqi Kurdistan, taught at the Prophet’s Mosque in Medina. During his career he shared his knowledge with a diverse array of students, and is especially revered in Indonesia. One of his students, Yusuf al-Makassari, who was exiled by the Dutch to South Africa in 1684 CE, is known as Shaykh Yusuf and is credited with introducing Islam to the Cape of Good Hope. The note on the last page of SAV ABS 03135 demonstrates that, during this same period, al-Kūrānī was teaching the pilgrim from Timbuktu. The manuscript captures an important meeting and transfer of knowledge, since the pilgrim al-Māsini would have passed on this valuable license to his own students upon returning to his city.

In other examples, manuscripts do not contain provenance notes but clearly have made long journeys from where they were originally copied down. Language can provide a clue to such origins. SAV BMH 34118, a commentary on the Qurʼan, has a gloss in Persian, while ELIT ESS 02952 is a collection of religious songs (İlâhiler) written in Ottoman Turkish.

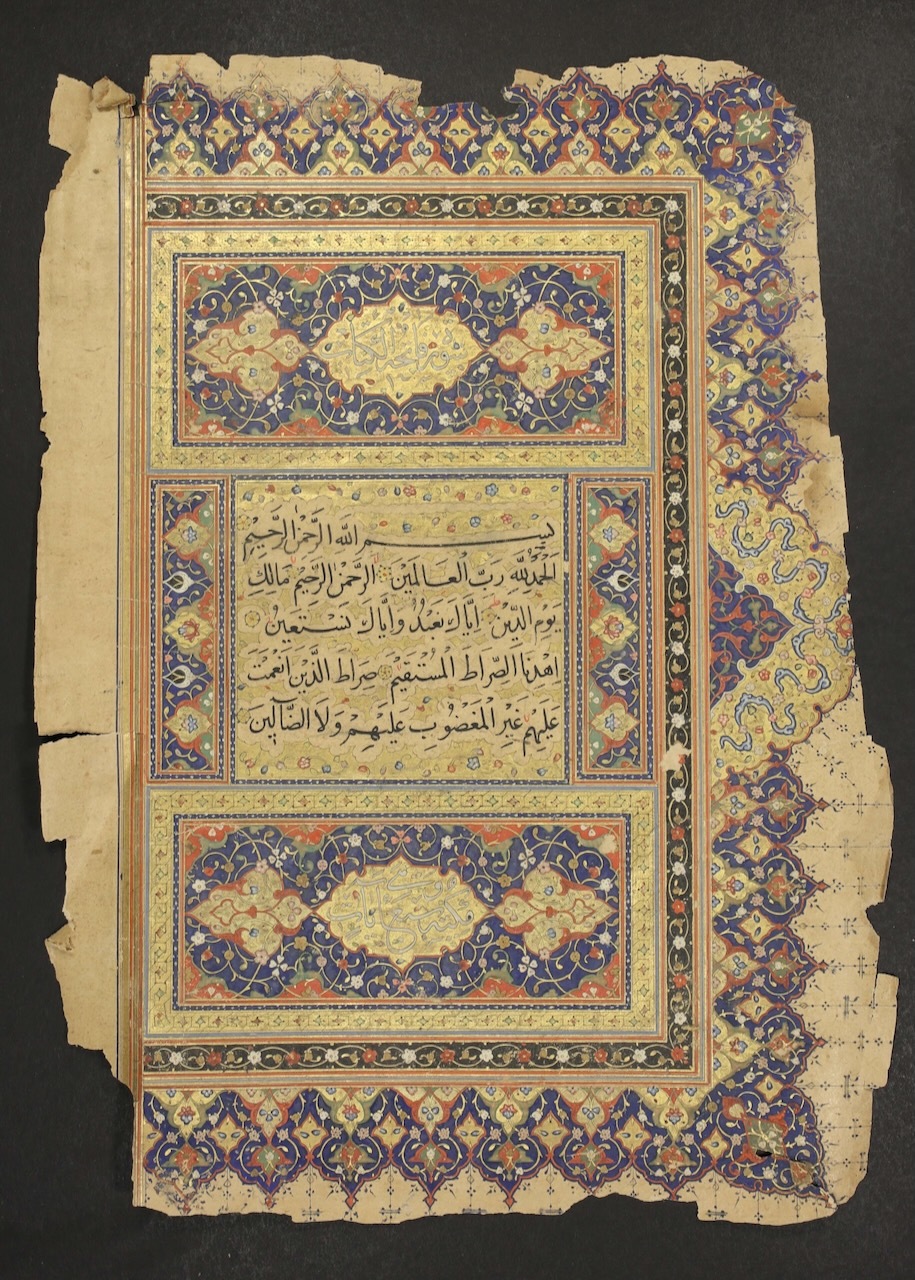

Decorative elements provide other clues. Copies of hadith collections, Maliki legal works, and the Qur’an would have been available locally, but copies may have been imported from elsewhere because of their rich and unfamiliar decoration. A stunning example of this is SAV BMH 34116, a Qurʼan with intricate illuminations very different to those of West African decorated Qurʼan copies but common in Iran.

Meanwhile, other texts may have been purchased not because of their physical appearance but because they concerned unfamiliar subjects.

ELIT ESS 00422 is a copy of Aḥmad al-Ghamrī’s history of Egypt. Its script tells us that it was produced outside of West Africa, and it is the only copy of this text found in HMML’s collections so far, so it was probably not commonly known. HMML’s Timbuktu collections include two copies of Ibn al-Ajdābī’s treatise on obscure Arabic words. Both copies were imported, suggesting this lexicographical work was not available locally. One of them, ELIT ESS 03933, is dated 9 Rabīʻ al-Awwal 628 AH (January 22, 1231 CE), making it the oldest manuscript identified in the Timbuktu libraries thus far. It contains notes in Hebrew as well as Arabic, suggesting that it led multiple lives before traveling to Timbuktu.

It is ironic that, despite the possibilities of rapid travel afforded by modern technology, people in West Africa today are less mobile than in previous times due to national borders, visa regimes, and the conflicts and economic problems affecting the countries of this region. The manuscripts, also, are not free to move like in times past. Most of the Timbuktu library collections digitized by HMML and our partners remain in Bamako due to ongoing instability in the north of Mali. Today the world is described as a global village. But the people and manuscripts of Timbuktu were global travelers long before our times.