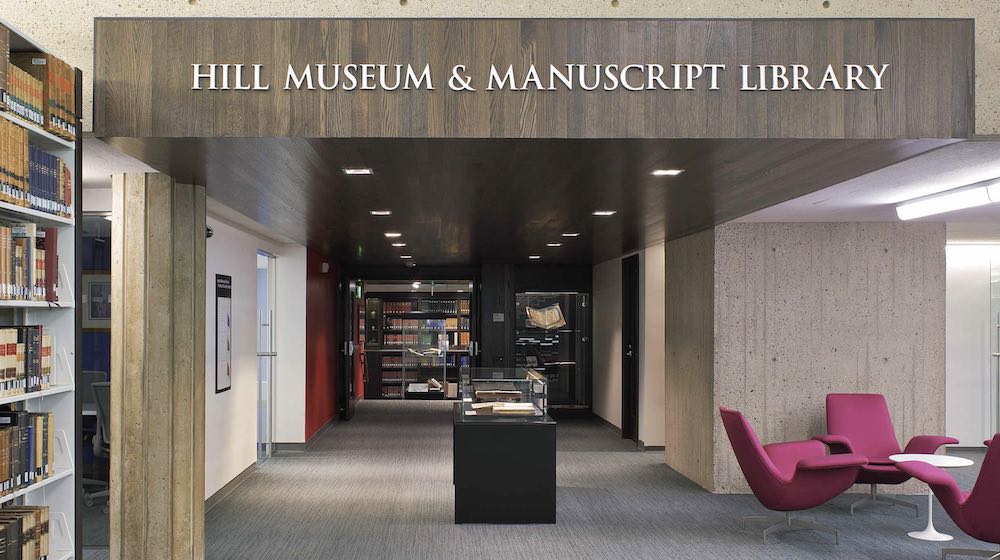

The Lord’s Song In A Foreign Land

The Lord’s Song in a Foreign Land

This story is part of an ongoing series of editorials in which HMML curators and catalogers examine how specific themes appear across HMML’s digital collections. From the Eastern Christian collection, Dr. Josh Mugler has this story about Migration.

In the middle of the 19th century, Arabic-speaking immigrants began to appear among the waves of newcomers arriving in the United States. The majority came from the region that is now Lebanon and nearby areas of greater Syria, which at the time were part of the Ottoman Empire. These new arrivals were generally members of Mount Lebanon’s many Christian sects.

Many of the new Syrian Americans settled in the urban centers of the Northeast, especially Boston, New York City, and northern New Jersey; some made their way inland and created communities across the Midwest and beyond. While many worked as street peddlers and in similar low-wage occupations, others found wealth in a variety of industries. Like so many Italians, Irish, Chinese, Scandinavians, and others of this era, Lebanese and Syrian immigrants came in search of economic opportunity and a better life for themselves and their families.

This growing community of Arabic-speaking Christians hoped to continue practicing their religion as they had in their former homes, but this required religious authorities, worship spaces, liturgical books, and other supplies. One priest who answered the call was Niqūlā Mudawwar (also spelled Nicholas Medawar).

Born in 1862 CE on the coast of northern Lebanon, Niqūlā Mudawwar was a member of the Melkite Greek Catholic Church and joined the Basilian Chouerite monastic Order, based at the monastery of St. John the Baptist in the mountains east of his hometown. Father Niqūlā served the Order in a variety of capacities and in different parts of Lebanon. In 1904–1905, he was sent to Australia to relieve a Melkite priest there, but that priest decided he would prefer to stay in Australia, so Fr. Niqūlā made the long journey home after only a short visit. In 1911, the head of the religious Order sent him to the United States; Fr. Niqūlā made the journey and would never return.

For most of his two decades in the United States, Fr. Niqūlā made his home in Danbury, Connecticut, where he played an important role in the founding and growth of St. Ann Melkite Catholic Church. Most of Danbury’s Melkites and other Lebanese immigrants worked in the hat industry. Fr. Niqūlā was not the first priest to minister to their community, but he was one of only a few Melkite priests in the country and, like other priests of his time, he felt a responsibility to the Syrian Christian community scattered throughout the United States.

He traveled by train from town to town, performing Arabic-language baptisms, marriages, masses, and other rituals that were badly needed by the isolated parishioners. Fr. Niqūlā spent significant time in Birmingham, Alabama, and New Orleans, Louisiana—showing just how far he was willing to travel to serve his community from his home in Connecticut.

Many of the places where Fr. Niqūlā stayed had mixed communities of Arabic speakers who were not necessarily Melkite but still valued the presence of a priest who could minister in their first language. In this way, he ended up worshiping with Maronites and other Catholics, as well as Eastern Orthodox Christians, whenever his services were requested. As the St. Ann Church website describes it, “Ecumenism is often regarded as a consequence of Vatican II, but these people lived it.” In the new context of the United States, sectarian tensions were reshaped and transcended, as necessity drove communities into new ways of navigating their religious practices.

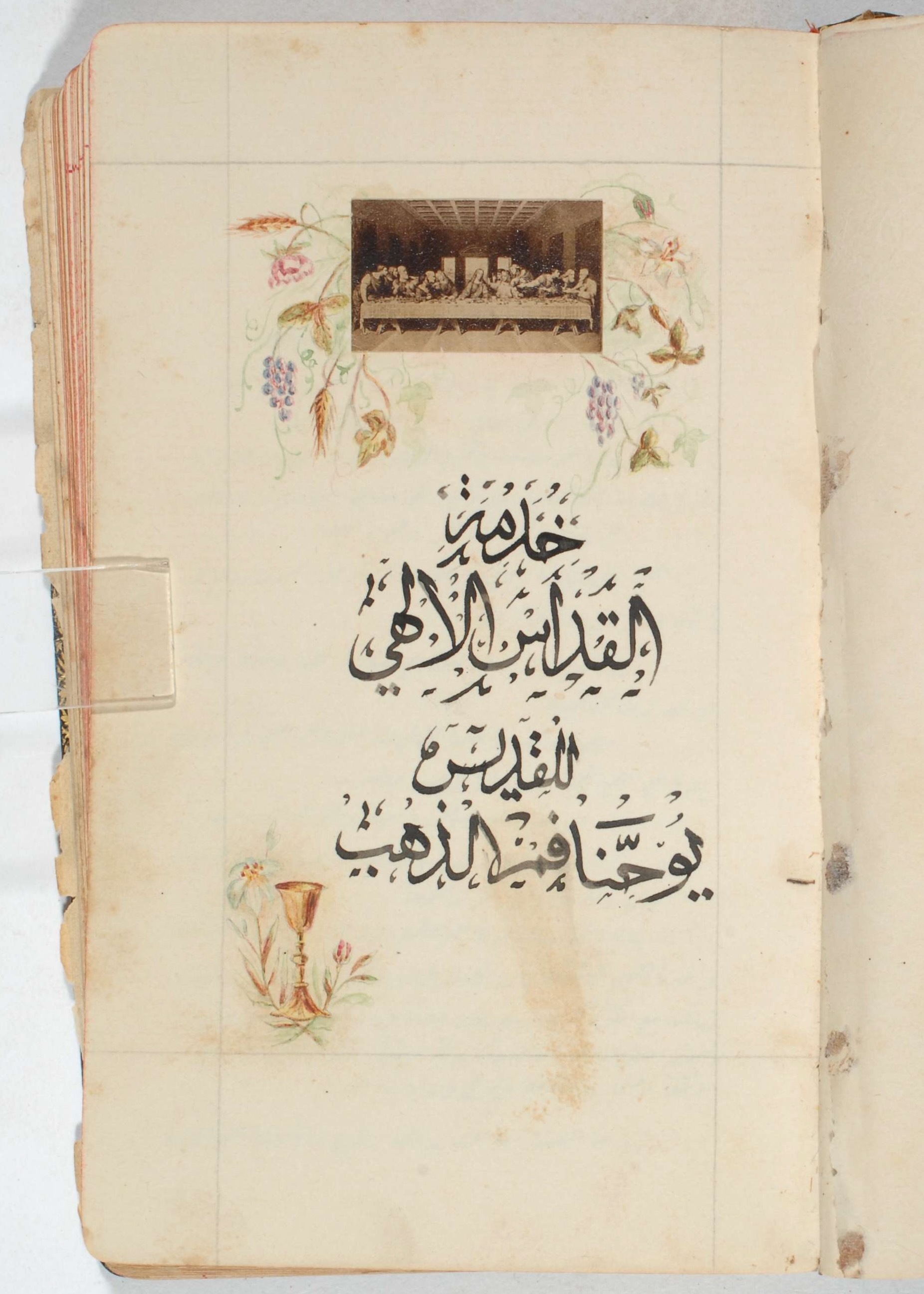

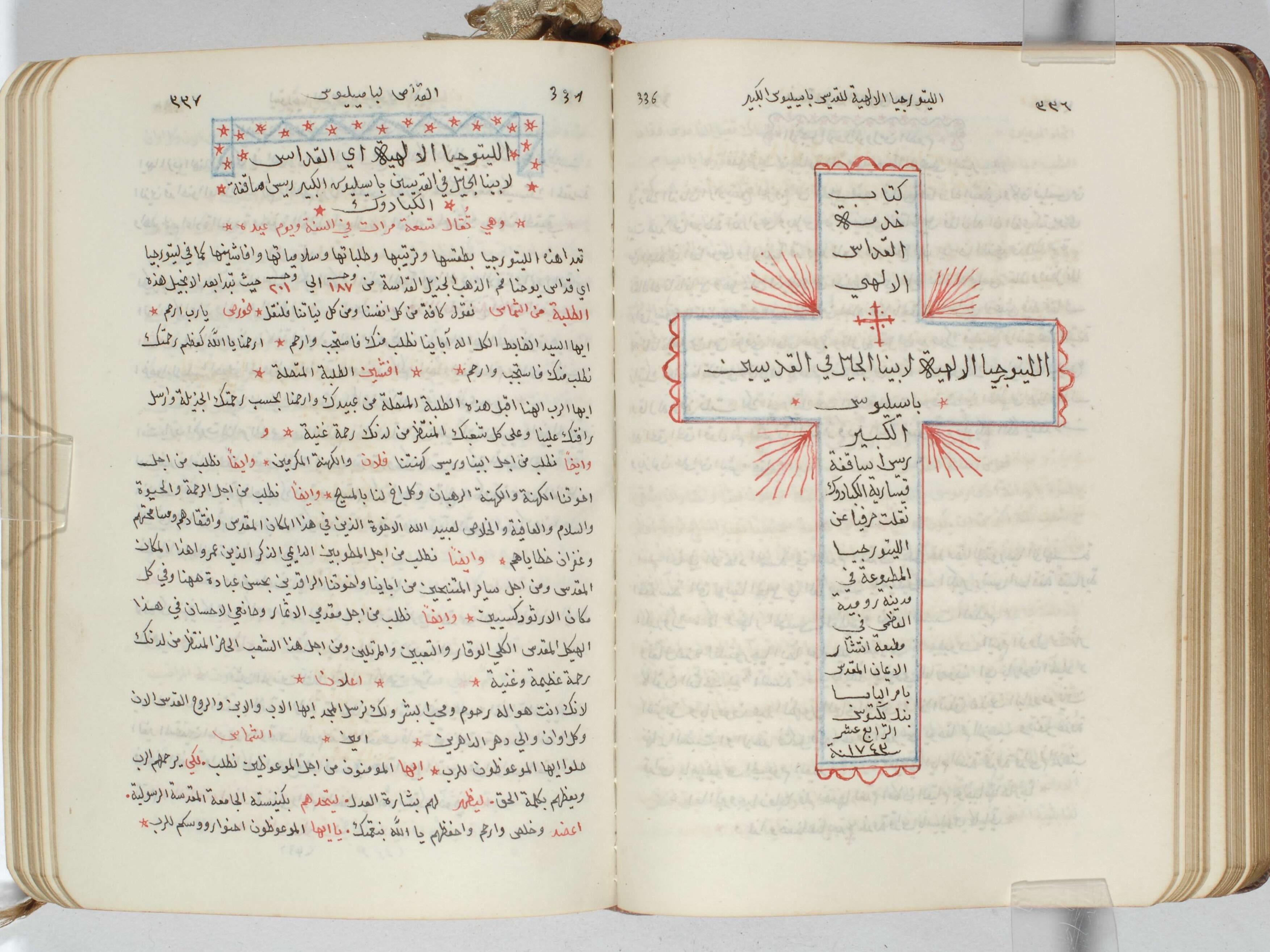

One project to which Fr. Niqūlā devoted significant time was the compilation of a liturgical book that he called al-Rawḍah fī al-ṣalawāt al-mafrūḍah, or “The garden of obligatory prayers.” This collection includes prayers and liturgical texts from all the major liturgical books of the Melkite Church’s traditional Byzantine rite, but edited and rearranged into a form that was more helpful for Fr. Niqūlā and his parishioners in the American context. Likely part of the appeal of this project was the possibility of including all the necessary texts in a single volume and thus avoiding the need to transport a full set of liturgical books across the country. On the other hand, the size of the book is noteworthy: the most complete copy in HMML’s collections (OBC 00181) stretches to 1,196 pages!

HMML has photographed three copies of al-Rawḍah, in various stages of completion and editing, as projects OBC 00179, OBC 00181, and OBC 00186. Several of these books are composite works copied at different times and assembled later, and OBC 00179 even includes a liturgical book printed at Fr. Niqūlā’s home monastery in Lebanon, bound into the middle of its otherwise handwritten pages.

The vast majority of the text in these manuscripts is copied in Fr. Niqūlā’s own careful Arabic hand, with devotional images occasionally pasted in to decorate the text. OBC 00181 seems to be the most final and full version of the compilation, completed on April 15, 1924. A label pasted into the back of the book shows that it was bound in Birmingham.

When Niqūlā Mudawwar died in 1929, his body was brought from Danbury to Worcester, Massachusetts, so that he could be buried next to his sister, another Lebanese American of New England. His bilingual Arabic/English tombstone still stands there today in Notre Dame Cemetery. At some point, his manuscripts were returned to his Order’s monastery in Lebanon, where they were digitized by HMML in 2007. Their preservation is a reminder of the global links that connect people from Beirut to Danbury to Birmingham and beyond.