Migrating Monastic Books In Minnesota

Migrating Monastic Books in Minnesota

This story is part of an ongoing series of editorials in which HMML curators and catalogers examine how specific themes appear across HMML’s digital collections. From Special Collections collection, Dr. Matthew Z. Heintzelman has this story about Migration.

On September 8, 1876, four boxes of books arrived at Saint John’s Abbey in Collegeville, Minnesota. Three and a half months later, another shipment of books arrived. These two shipments doubled the size of the fledgling monastic library at Saint John’s. Though both shipments arrived in Minnesota in similar ways, their paths were in fact quite different and today provide us with insight into the turbulent history of the Benedictines in the first half of the 19th century.

The first shipment of 1,062 volumes (922 distinct titles) came from Ottobeuren Abbey and the second, from the Abbey of Metten, provided an additional 179 volumes (116 distinct titles).

Saint John’s had been growing a book collection during the first two decades since its founding, but it was not until 1875 that a more official library—complete with a log of its accessions—was established. Perhaps someone’s report of this new establishment prompted a generous response from the monastic communities at Ottobeuren and Metten; however, I cannot verify that hypothesis. We do know that the Benedictine tradition values the role of books in monastic formation and spiritual development (among other matters), so a large gift of books from one Benedictine community to another is not too surprising.

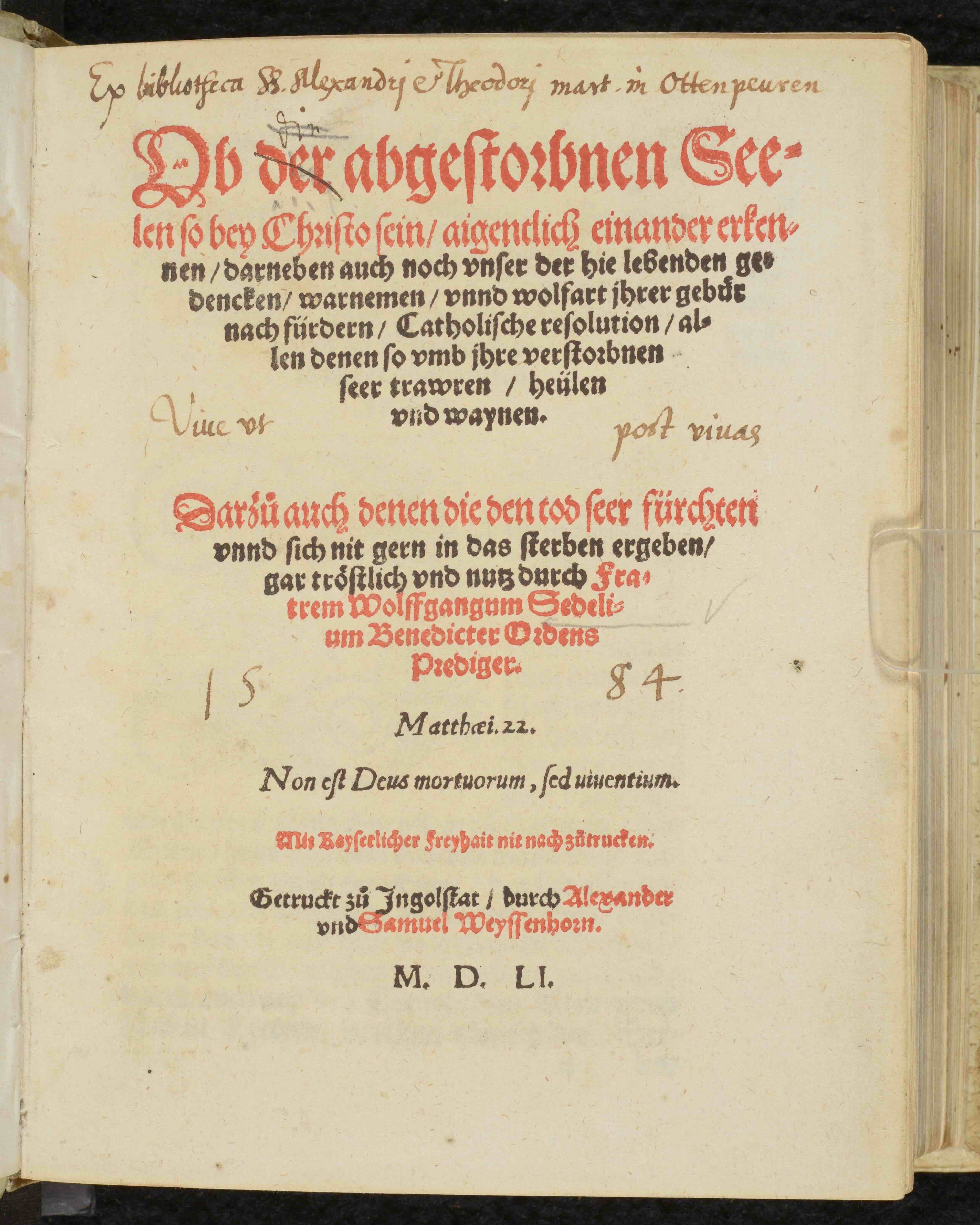

The gifts from Metten and Ottobeuren focused on Roman Catholic theology, church history, homiletics, and canon law. The books were chiefly in Latin and included editions of printed books—published in the 15th to the 18th centuries—that were duplicates of copies in use at the Ottobeuren and Metten libraries. Interestingly, to this day, we find that many of the books gifted from these two libraries may be the only copies of a particular text or edition documented thus far in a North American library. Today, these books are kept in the rare books collection of Saint John’s University, which is administered by HMML.

Despite all their similarities, the two donations have strongly distinctive characteristics.

Clues Under (and on the) Cover

The books from Ottobeuren mostly bear an ownership note from that abbey on the title page, often with the date they acquired the book (occasionally within couple years of its publication). None of the volumes from Metten bear ownership notes of the Metten library; rather, they contain ownership notes of individuals or of other monastic communities.

Many (though not all) of the Ottobeuren books have a uniform look: bound in white pigskin over heavy wooden boards. Many still have clasps to hold the covers tightly shut (a protection against warpage). The Metten books—on the other hand—are bound in many different styles, and many of the spines utilize plain paper (or remnants thereof) with modern labelling.

These physical clues in the books point us to the paths of migration which brought them to Minnesota from their Bavarian homeland.

Closure and New Beginnings

In the very early 19th century, the Bavarian duke (and soon to be king) Maximilian I Joseph (1756–1825) ordered the secularization of all monasteries in his lands. Upon that order, the properties of these communities, some of them over a thousand years old, reverted to the government. Included in this seizure of property were the monasteries’ extensive book and manuscript collections. As a result, the Bavarian State Library today holds one of the world’s largest collections of 15th-century printed books (“incunabula”) and medieval manuscripts.

The abbeys at Metten (founded in 766) and Ottobeuren (founded in 764) suffered this same fate, with one primary distinction: after the closure of Ottobeuren in 1802–1803, a few monks were permitted to remain at the monastery, while Metten’s closure resulted in the monastery being completely vacated. The library at Ottobeuren was locked, but most of the books remained there. Metten’s books were dispersed, given to the court library in Munich, university libraries, and elsewhere.

Maximilian’s son, King Ludwig I of Bavaria, granted permission to re-open Metten Abbey in 1830. A few years later, in 1835, Ottobeuren was re-established as a priory of a monastery in Augsburg, eventually becoming an independent monastery in 1918.

The migration of Benedictine life to North America as we know it rested upon Maximilian’s restoration of monastic houses. One of the young monks at Metten was Boniface Wimmer, OSB, who went on to found the community of Saint Vincent’s in Latrobe, Pennsylvania, in 1846. Under his leadership, the community in Latrobe sent a contingent of monks to central Minnesota, where they established Saint John’s Abbey and University.

Continuance

After the restoration of Metten Abbey, the Metten community was able to receive about 300 volumes back from its earlier collection, but they otherwise had to resort to purchasing books and receiving remnants of collections from other houses that had been closed. The new acquisitions were not re-bound in a unified style.

In the Saint John’s collection, one can see the impact of these different histories on the books themselves. Having been moved repeatedly and passed through numerous hands, the books from Metten are often not in as good a condition as those from Ottobeuren. The paper remnants on many of the Metten spines may also point to the books having been warehoused at some point, with temporary labels to simplify the sorting and storing.

Still today, the majority of books in the rare book collections at HMML and Saint John’s have come as gifts. In 1876, these two large donations of books from Bavarian monasteries put Saint John’s library on the map. However, these two donations from nearly 150 years ago also tell us of the struggles that Benedictine monasticism encountered on its own migration to North America.

I’ve had the great fortune of visiting these libraries of that are a part of the roots of Saint John’s. When one enters the Baroque library at Ottobeuren, one can see why white pigskin bindings were so beloved there; the space is designed in a way that the books can become a part of the overall architectural plan, providing a bright and evenly-white contrast to the surrounding painting and woodwork. That consistency of design and Metten’s variety carry their histories forward, in the volumes that they passed on to their Benedictine “cousins” in Minnesota.