Medical Texts From Timbuktu — Local Pharmacological Remedies With Qur’anic Verses

Medical Texts From Timbuktu — Local Pharmacological Remedies with Qur’anic Verses

This story is part of an ongoing series of editorials in which HMML curators and catalogers share their discoveries, focusing on a theme that travels throughout HMML’s collections. Examining the theme of Medicine, Dr. Ali Diakite and Dr. Paul Naylor share this story from the Islamic collection.

In West Africa, knowledge of the Qur’an was often combined with local pharmacological traditions to achieve a certain benefit called Fāʼidah (see a recent Postscript article in HMML Magazine for an example). For HMML’s series of articles on medicine we delve deeper into this genre of writings.

“Qur’anic medicine”—using the text of Islam’s holy book, the Qur’an, as a medicinal cure—has long been a part of Islamic spirituality. Certain chapters (Sūrahs) of the Qur’an such as Sūrat Yāsīn are deemed to be particularly powerful, and individual verses (āyāhs) are said to cure particular ailments.

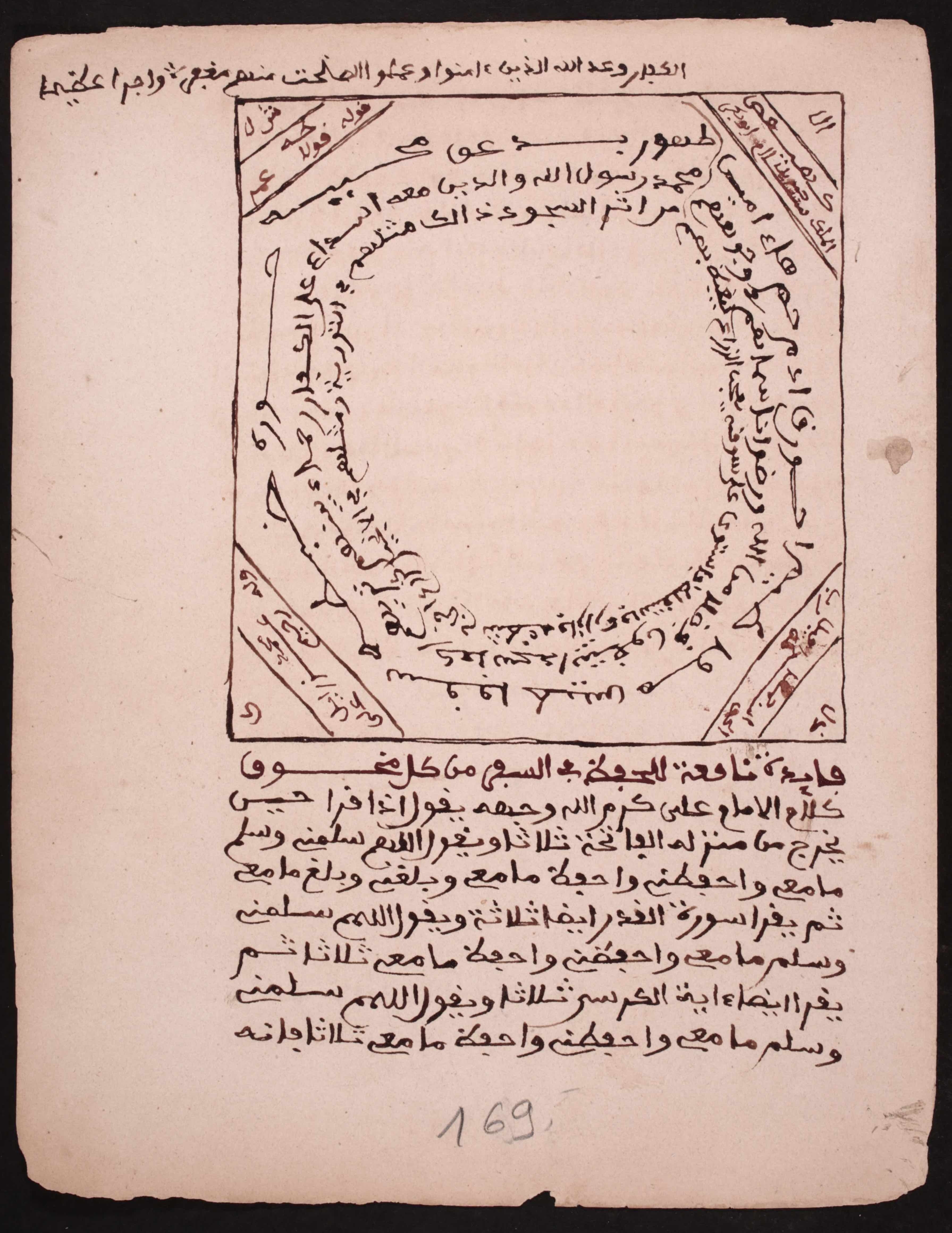

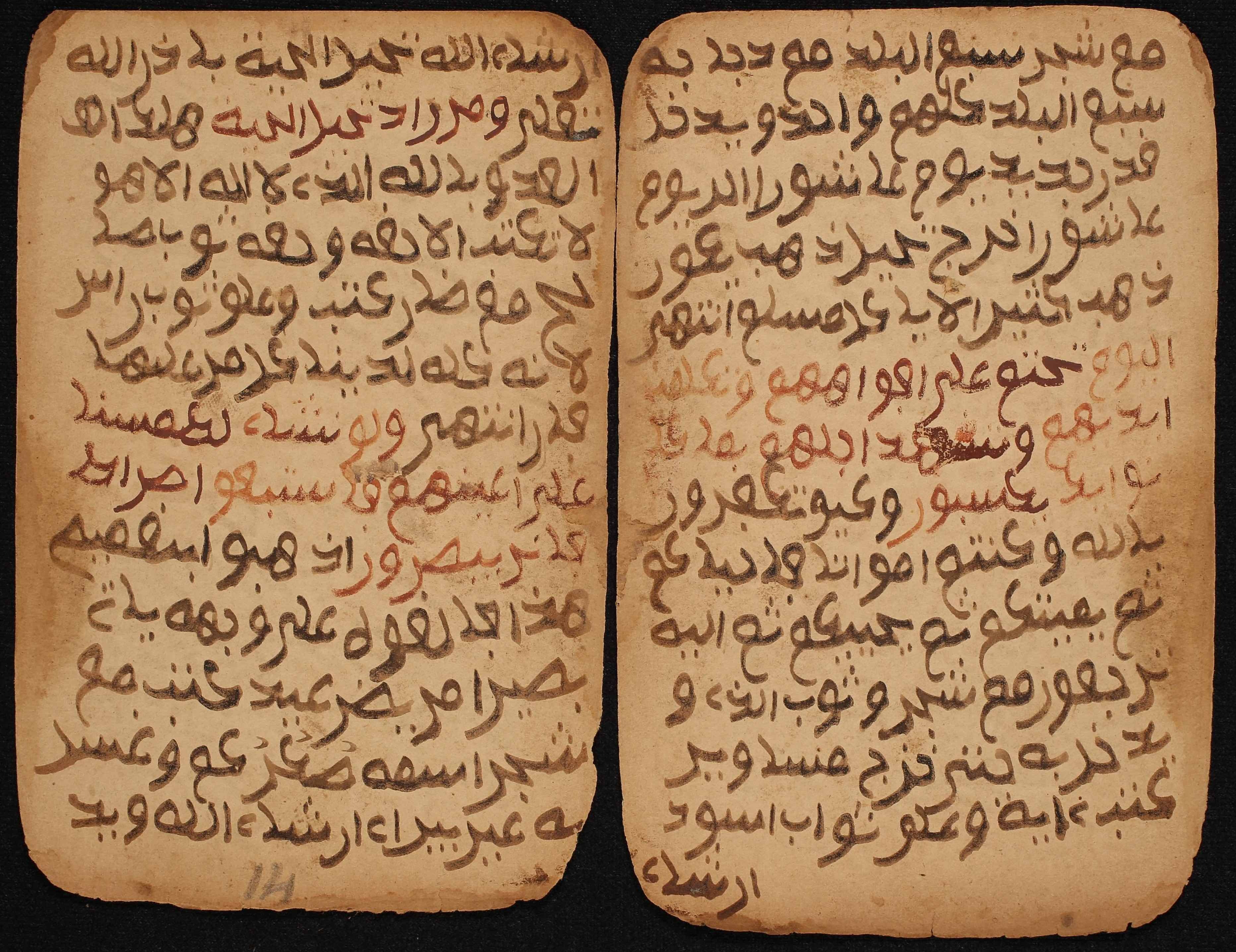

HMML’s digital collection of manuscripts from Timbuktu contains numerous examples of such handbooks of Qur’anic medicine. However, in many cases the benefit of the āyahs works in tandem with West African traditional medicine. For example, take the manuscript that HMML identifies as SAV ABS 02570. In the text, each āyah of Sūrat Yāsīn appears in red (rubricated) text, usually followed in black ink by a related verse from another part of the Qur’an and the beneficial medicinal uses of these verses. Most entries include the names of local trees and plants (in Bambara, as well as other local languages) and instructions as to their preparation and interaction with the verse in question.

Here are two examples from the text of SAV ABS 02570.

Page 14v.:

“If it had been our Will, We could surely have blotted out their eyes; then should they have run about groping for the Path, but how could they have seen?” [Qur’an 36:66]

“Go with this my shirt, and cast it over the face of my father: he will come to see [clearly]” [Qur’an 12:93]

For those with damaged eyes, write [out the āyahs] with the tree called Ṣukuru KM and wash the eyes with it and he will see, if God wills.

The second Qur’anic verse in this example refers to the story of Prophet Joseph. His father was cured of blindness by rubbing his face with Joseph’s cloak. Unfortunately, we have not been able to identify the tree named Ṣukuru KM.

Page 19r.-20v.:

“Glory to Allah, Who created in pairs all things that the earth produces, as well as their own (human) kind and (other) things of which they have no knowledge.” [Qur’an 36:36]

“O Prophet! Why holdest thou to be forbidden that which Allah has made lawful to thee? Thou seekest to please thy wives.” [Qur’an 66:1]

Attach [these verses] to the woman who wants to have a child with the tree called Turu [Ficus sycomorus]. Even if she is old, if God wills she will have a child.

In this case, the two verses were presumably chosen because they both include the Arabic word azwāj, literally “pairs” but also taken to mean husbands and wives. “Attach” here means to write out the verses and tie them onto clothing or on a pendant to be worn by the patient as an amulet.

It is difficult to say exactly when this genre of medical cures emerged. However, the texts have much in common with earlier medical manuals from West Africa such as Shifāʼ al-asqām al-ʻāriḍah fī al-ẓāhir wa al-bāṭin min al-ajsām (Curing diseases and defects both apparent and hidden), collection item SAV BMH 00116. The text was written by Aḥmad al-Raqqādī (died 1681 or 1684), who was from the Kunta family of scholars. It also details the benefits of Qur’anic āyahs for a range of medical uses. However, the cures require expensive imported ingredients such as saffron, rose water, and silks (the Kunta were merchants who likely profited from the trade of these items across the Sahara!). What is more, the author was more interested in lofty challenges, such as divining the destiny of an unborn child or developing a prodigious memory, rather than common maladies like backache and poor eyesight.

In most Bambara-speaking regions, large-scale conversion to Islam occurred only in the nineteenth century. Thus pre-existing pharmacological traditions became fused with the Qur’anic medicine that was taught and practiced by Muslim scholars. Most likely these manuscripts, which probably date to the same period, are the result of local transmission and elaboration upon earlier works like Shifāʼ al-asqām, using ingredients that were close to hand and whose efficacy was already attested by generations of herbalists.