An Anonymous Syriac Medical Compendium

An Anonymous Syriac Medical Compendium

This story is part of an ongoing series of editorials in which HMML curators and catalogers share their discoveries, focusing on a theme that travels throughout HMML’s collections. Examining the theme of Medicine, Dr. James E. Walters shares this story from the Eastern Christian collection.

Many medical works from antiquity were translated into Syriac and transmitted through the centuries as part of a sizeable body of medical literature. HMML has digitized such texts, as well as medical texts originally written in Syriac, such as the Questions on Medicine for Students by Ḥunayn ibn Isḥāq (manuscript CPB 00423) and the Syriac Book of Medicines (DFM 00417 and QACCT 00149).

In the medieval middle east, it became common to collect medical knowledge into user-friendly reference books known as medical compendia. These medical texts generally contain both descriptions of illnesses and the collected wisdom on known remedies. Some of these texts have been lost over time and are known only through citations or references to them in other works. Sometimes we’re lucky, and what was thought to be lost is found again.

For example, recently HMML cataloger Grigory Kessel identified a very important Syriac medical compendium: the Kunnāšā, by 9th-century author Īšōʿ bar ʿAlī. Texts like the Kunnāšā served as a model for Arabic medical compendia such as the Book of Treasure in the Science of Medicine (attributed to Thābit ibn Qurra), the Paradise of Wisdom (attributed to ʿAlī Ibn Sahl aṭ-Ṭabarī), and the Book of the Hundred (attributed to Abū Sahl al-Masīḥī).

Inside One Compendium: Manuscript DFM 00696

While medieval medical writings in Arabic far outnumber those written in Syriac, medical texts were transmitted in various forms in Syriac literature well into the modern period. Such is the case with manuscript DFM 00696. This manuscript is held in the library of the Dominican Friars of Mosul in Iraq and was digitized by HMML in 2012.

The text is written in a very clear East Syriac script. The manuscript lacks a formal title and colophon; it is possible such pages existed, but if so they have not survived. Without a colophon there is no description of the manuscript’s production details, such as the date it was copied. While the language of the text is Syriac, it seems to incorporate both Arabic and Neo-Aramaic vocabulary, suggesting a rather late date of composition (probably 18th-19th century).

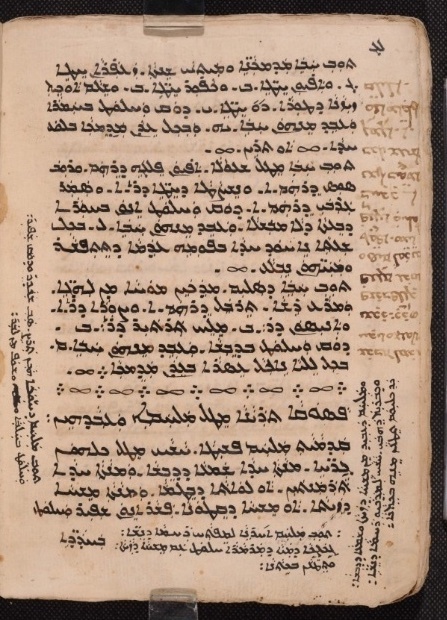

Throughout the manuscript there are many marginal notes, some of which appear to have been added by later hands. Some of these notes are corrections to the text while others provide more detail or supplement the text in various ways, suggesting that this manuscript was consulted by various readers over time.

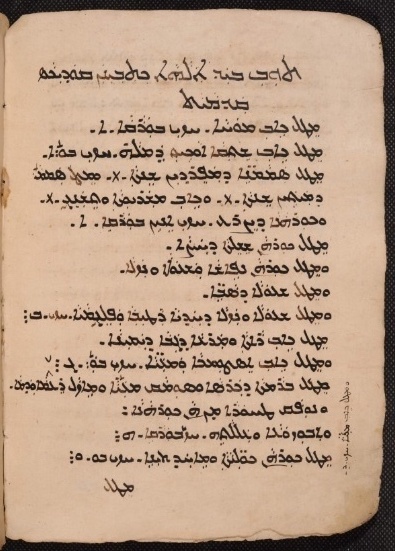

The main text of DFM 00696 begins with a table of contents (folios 5v-8v), with the book organized into chapters and sections.

As can be seen from the table of contents, the work is structured topically, beginning with “Disease of the Brain” (ܟܐܒ ܡܘܚܐ). The topics treated here are not “headaches,” but appear to be in fact mental illnesses of various causes.

Disease of the Brain

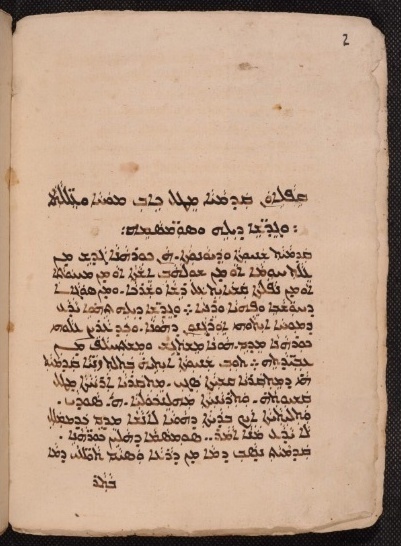

This section opens with the author informing us that this particular sickness (ܟܘܪܗܢܐ) can be caused by a number of things, including: heat (ܚܘܡܐ), inflammation of a fever (ܫܘܠܗܒ ܐܫܬܐ), a blow or wound (ܡܚܘܬܐ), or from falling on one’s head (ܢܦܠܬܐ ܩܫܝܐܝܬ ܥܠ ܪܫܐ). The text then goes on to offer tips for recovery (ܣܘܡܣܡܐ) from these illnesses. Each illness covered in the text follows more or less the same structure: first a list of potential causes and descriptions of the sickness, followed by suggested remedies.

Chapter 1 (“Disease of the Brain”) contains the following section topics: “Silence of speech” (ܤܬܩܐ ܗܝ ܕܡܠܗ); “events that occur during slumber” (ܓܕ̈ܫܐ ܕܥܪܨܝܢ ܥܠ ܢܘܡܬܐ); “calming remedies for sleep” (ܣܡܡܢ̈ܐ ܡܫܠܝܢܐ ܘܕܡܝܬܝܢ ܫܢܬܐ ܘܢܘܡܬܐ); “paralysis and feebleness” (ܟܐܒ ܡܫܪܝܘܬܐ ܘܫܦܠܘܬܐ); “sickness of the breast” (ܟܘܪܗܢܐ ܕܨܪܥ); and “sickness of a clot [?] of the back/loin” (ܟܘܪܗܢ ܫܫܠܬܐ ܕܚܨܐ). This final section is immediately followed by a heading for “Chapter 2: Sickness of the Lungs” (ܟܘܪܗܢܐ ܕܢܦܐܫܐ ܘܐܘܪܓܢܘܢ ܕܝܠܗ).

Breadth of Medical Topics

The manuscript contains many topics that are common to medical compendia, including:

- Stomach and bowels (ܟܐܒ ܐܣܛܘܡܟܐ ܘܡܥ̈ܝܐ) – fol. 13r

- Ears (ܡܪܥ ܐܕ̈ܢܐ) – fol. 16v

- Eyes (ܟܐܒ ܥܝ̈ܢܐ) – fol. 17r

- Nose (ܟܐܒ ܢܚܝܪܐ) – fol. 18r

- Mouth (ܟܐܒ ܡܪܥ ܦܘܡܐ) – fol. 18v

- Headaches (ܡܪܥ ܪܫܐ) – fol. 19r

- Gall/Liver (ܟܐܒ ܟܒܕܐ) – fol. 20r

- Kidney/Spleen (ܟܐܒ ܛܚܠܐ) – fol. 20v

- Faranji (ܦܿܪܢܓܝ) – fol. 22r. Note: The word “Faranji/Paranji” (i.e. “Frankish”) has been used by some cultures to mean “syphilis,” but in the present manuscript it seems to refer more broadly to a skin disease.

- Leprosy (ܓܪܒܐ) – fol. 23r

- Heart (ܟܐܒ ܠܒܐ) – fol. 23v

- Sicknesses affecting children (ܟܘܪܗܢ ܛܠܝ̈ܐ) – fol. 23v

- Sicknesses affecting men in particular (ܟܘܪܗܢܐ ܕܓܒܪ̈ܐ ܦܪ̈ܝܫܐܝܬ) – fol. 24v

- Sicknesses affecting women in particular (ܟܘܪܗܢܐ ܕܢܫ̈ܐ ܦܪ̈ܝܫܐܝܬ) – fol. 25v

- Bite/sting of a poisonous animal (ܢܘܟ̈ܬܐ ܕܚܝ̈ܘܬܬܐ ܡܣܡ̈ܡܐ) -fol. 27r

- Snakebite (ܢܘܟܬܬ ܚܘܝܐ) – fol. 28r

- Boils/ulcers (ܟܘܪܗܢ ܦܬܩܐ) – fol. 33v

- Stones in the urine (i.e. kidney stones ܟܐܦܐ ܕܗܘܬ ܒܬܝܢܬܐ) – fol. 34r

- Open wounds, like sword or knife [stabs] (ܓܪ̈ܚܐ ܦܬܝ̈ܚܐ ܐܝܟ ܣܝܦܐ ܐܘ ܣܟܝܢܐ) – fol. 35v

- Burns (ܝܩܕܢܐ ܕܢܘܪܐ) – fol. 37r

The second half of the book is composed of two additional texts. A new title appears on fol. 38v, but it is unclear if this title should be regarded as a distinct work or as one part of a larger work. The title here is the “Book of correction of medicines” (ܟܬܒܐ ܕܬܘܪܨ ܣܡܡ̈ܢܐ). This pharmacological work, also arranged into sections, takes up most of the rest of the manuscript (fol. 38v-59v), and it is followed by another distinct title: “Teaching and the manner of sicknesses and their remedies” (ܝܘܠܦܢܐ ܘܐܝܟܢܝܘܬܐ ܟܘܪܗܢܐ ܘܣܘܡܣܡܐ ܕܝܠܗܘܢ), fol. 60r-65v.

One interesting feature of the DFM 00696 medical compendium is that the manuscript, which was likely based upon some other medical compendium or treatise, seems to intentionally obscure its source material. No other works or authors appear to be quoted in the text. It is possible, of course, that some source material may be found in other extant Syriac or Arabic medical works, but such identification would require more in-depth research.