Accounts On Plague And Infectious Diseases From Three Arabic Manuscripts

Accounts on Plague and Infectious Diseases from Three Arabic Manuscripts

This story is part of an ongoing series of editorials in which HMML curators and catalogers share their discoveries, focusing on a theme that travels throughout HMML’s collections. Examining the theme of Medicine, Dr. Celeste Gianni shares this story from the Islamic collection.

The disastrous impact of plague epidemics in the Middle East has been documented in numerous accounts transmitted by Muslim scholars, from the first epidemics that occurred since the time of the early Muslim conquests in the 7th century, with an increase of narratives from the period of the Black Death in the 14th and 15th centuries, up to the 19th century epidemics of plague.

Three Arabic manuscripts in HMML Reading Room seem to point towards an interesting shift in approaches to infectious diseases by the Muslim scholars in the Middle East. Two of the texts are from the 15th century and one is from the 17th century, part of the Issaf Nashashibi Center for Culture and Literature and Āl Budeiry collections in Jerusalem.

Theological Approaches to Infectious Diseases

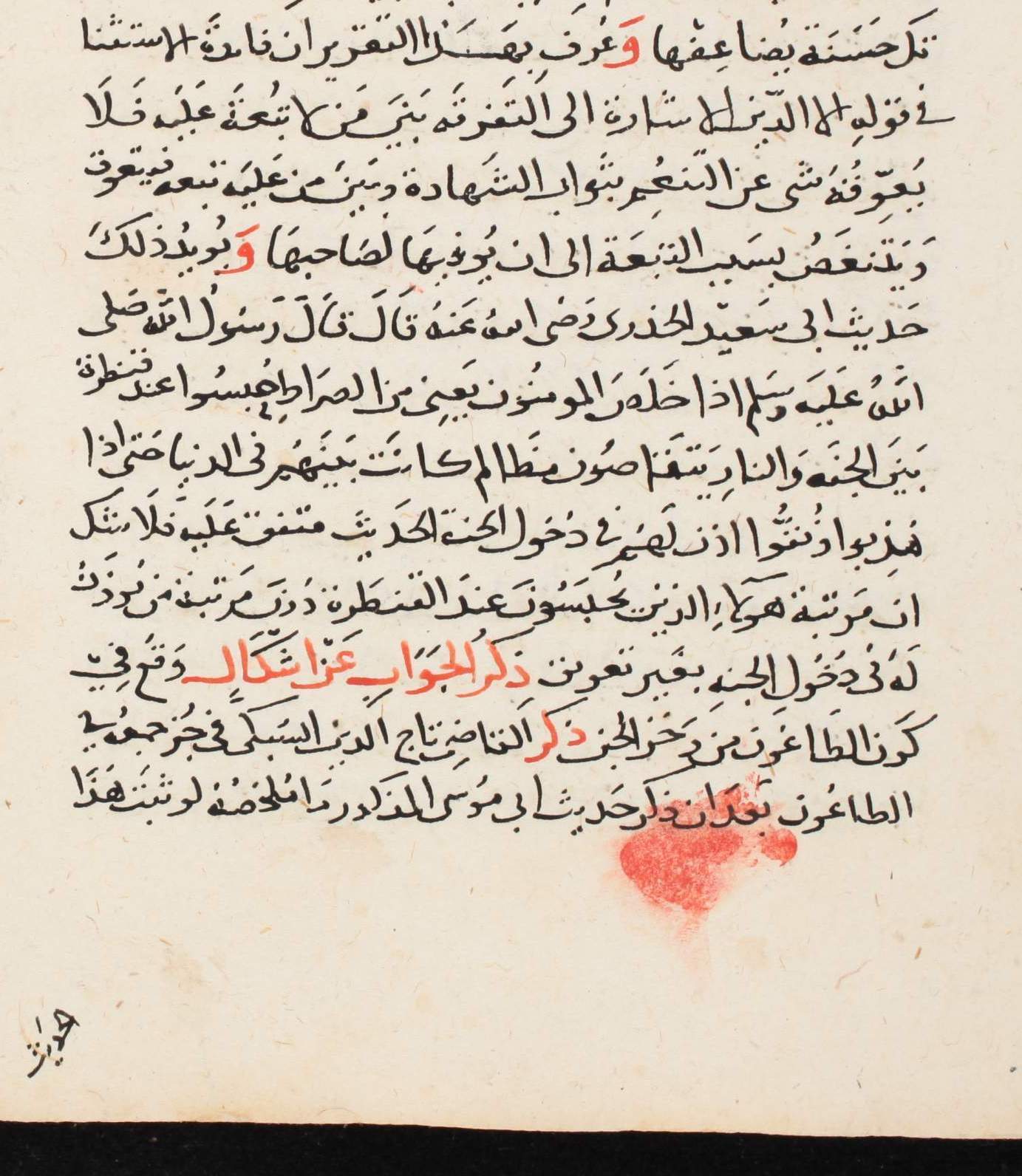

The most renowned work on plague written in Arabic, Badhl al-māʻūn fī faḍl al-ṭāʻūn (An Offering of Kindness on the Virtue of the Plague), by Ibn Ḥajar al-ʻAsqalānī (1372-1449), is included in manuscript ABLJ 01158, a 17th-century copy of the text. This famous Egyptian polymath scholar and theologian lost three daughters because of the Black Death that affected Cairo at the beginning of the 15th century. His treatise on plague stresses a contemporary Islamic theological justification of deadly epidemics seen as a blessing from God.

At the time, infectious diseases were still explained in conformity with the Galenic medicine and the miasma theory that asserted that plagues occurred as a result of an imbalance of the four bodily humors, caused by the corruption of air. Based on numerous Prophetic traditions, Ibn Ḥajar establishes that the cause of the imbalance of humors as described by Galen is in fact due to the action of a supernatural being, an “evil Jinn” piercing the human body and causing this imbalance.

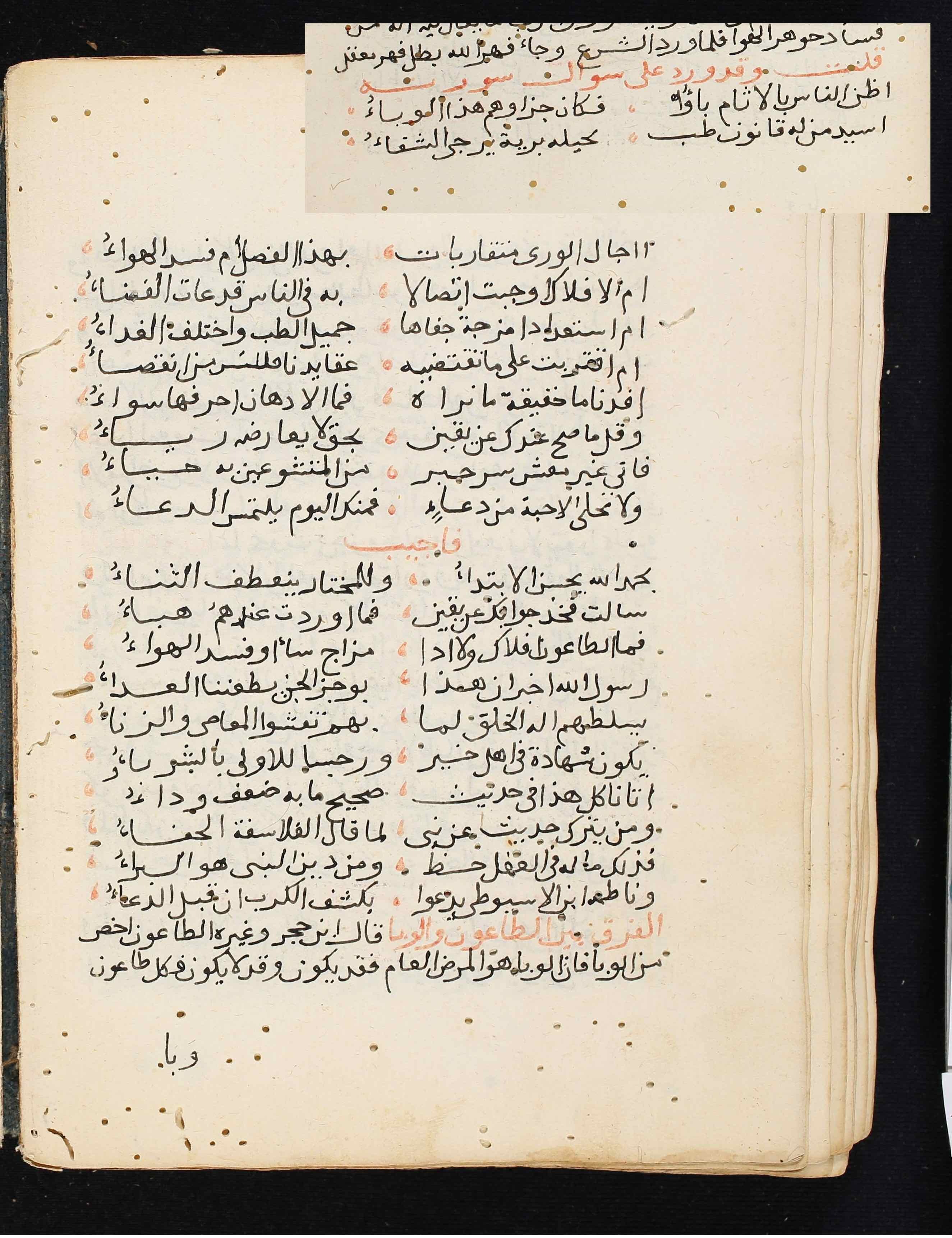

This theological approach was embraced by the Egyptian scholar and jurist Jalāl al-Dīn al-Suyūṭī (1445-1505). DINL 00056 180 (fol. 137v-152r) is a 17th-century manuscript that includes Suyūṭī’s collection of accounts on the plague, Mā rawāhu al-wāʿūn fī akhbār al-ṭāʿūn (Knowledgeable Accounts on Stories of the Plague). Within this collection of accounts that recall the Prophetic traditions, Suyūṭī includes a poem where an unknown person asks the author questions on the causes of plagues:

I believe people committed many sins,

So they were punished by this epidemic,

Oh master, who knows the cure for the plague?

Is this the predestined time for so many people to die?

Or is this due to the corruption of the air?

Are perhaps the celestial bodies to be blamed for the death of so many people?

Or did this occur due to the imbalance of humors?

Was it rather the result of changing our diet?

Or is it the Day of Judgment approaching us?

And Suyūṭī’s response follows:

…

Plague is not caused by celestial bodies,

Nor by the imbalance of humors,

Or the corruption of air;

The Prophet told us that this happens when a Jinn stabs his enemies;

The Creator gave to Jinns the power to act when sins are spread among humans;

It is martyrdom for the good people, and punishment for the sinful ones.

…

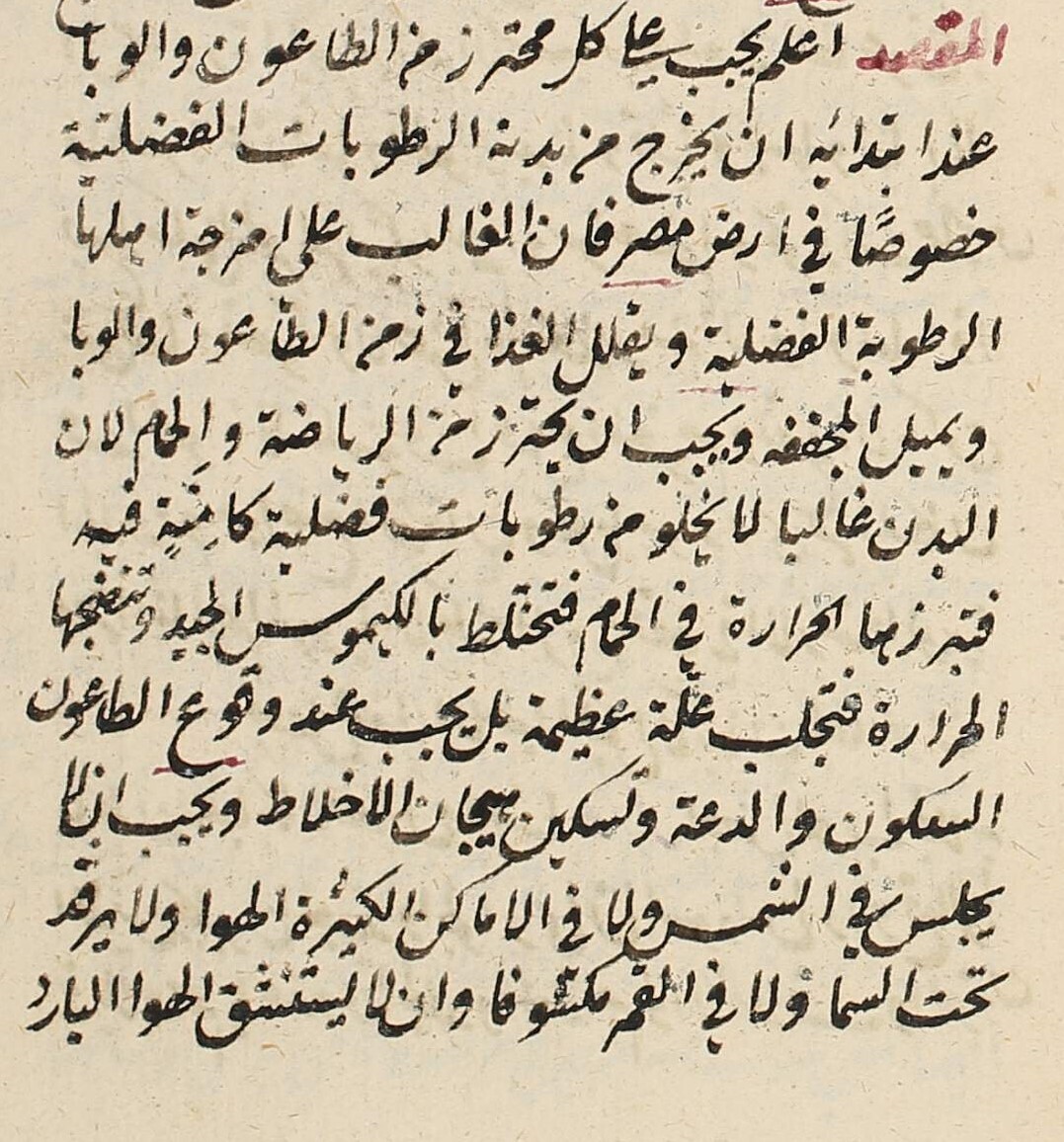

Towards a Medical Approach

By the 17th century, a more practical approach to the disease seems to replace the 15th century theological approach, as it emerges from the little-known work, al-Durr al-maknūn fī al-kalām ʻalá al-ṭāʻūn (Hidden Pearls on Discussing the Plague) by Aḥmad ibn Muḥammad al-Ḥamawī (died 1686 or 1687), found in a copy dated 1713 CE in manuscript ABLJ 01144 074 (fol. 96r-102v).

Al-Ḥamawī was a Ḥanafī scholar who grew up in Cairo and had expertise in a wide range of subjects. In this treatise, al-Ḥamawī reverses the scholarly tradition that discussed the topic of the plague within the Prophetic tradition; instead, he starts with the description of the disease’s pathology and aetiology by referring directly to Galenic medicine, as well as listing possible treatments and cures, and the best practices to avoid contagion. Only at the end of the treatise he quotes the traditional Prophetic sources discussing infectious diseases.

In the introduction, al-Ḥamawī lists symptoms and remedies for curing the plague. He discusses at length the benefits of applying Armenian clay on the skin (fol. 98rv), and recommendations such as (fol. 96v-97r):

“…administering medicines that strengthen the heart, like the thickened liquid of sour dock and apple and quince, pomegranate, and the inhalation of burnt sandal, rose and camphor; eating chicken, zirbag [a meal consisting of spiced meat sprinkled with saffron and vinegar], and lentils”

Al-Ḥamawī avoids discussing the theological causes of plague; instead, he underlines the importance of the environmental factors, saying, “Everyone that has been affected by the pandemic of the plague should flee from the damp and humid areas as soon as possible, especially in Egypt” (fol. 97r).

He discusses preventive measures to stop the spread of diseases, and reports on how the slave trade from the coasts of East Africa was contributing to the spread the plague (fol. 97v-98r), thus opposing the predestination aspect of the theological approach for which preventive measures were pointless.

Further research into Arabic medical texts from the 17th century onwards should be carried out in order to understand if al-Ḥamawī’s treatise is representative of a broader shift in thoughts on contagious disease in the Middle Eastern society at the time or if it is an exception among the mainstream Prophetic tradition.