Woodcut Fragments Of The 16th Century

Woodcut Fragments of the 16th Century

This story is part of an ongoing series of editorials in which HMML curators and catalogers examine how specific themes appear across HMML’s digital collections. From the Art & Photographs collection, Katherine Goertz shares this story about Fragments.

HMML’s Art & Photographs collection is full of fragments of the 15th and 16th century. Almost all were clipped from their original volumes decades or even centuries ago. Many are very small—some about the size of a postage stamp, a few as large as a postcard, most are somewhere in between. Some are mounted on album pages, others are loose. Many came to HMML stored in mailing envelopes but are now kept in archival folders and boxes.

Since they have been entirely removed from their context and are very rarely signed, the source of fragments like these is often unidentified. However, a few in the Art & Photographs collection have recently been matched to their original books.

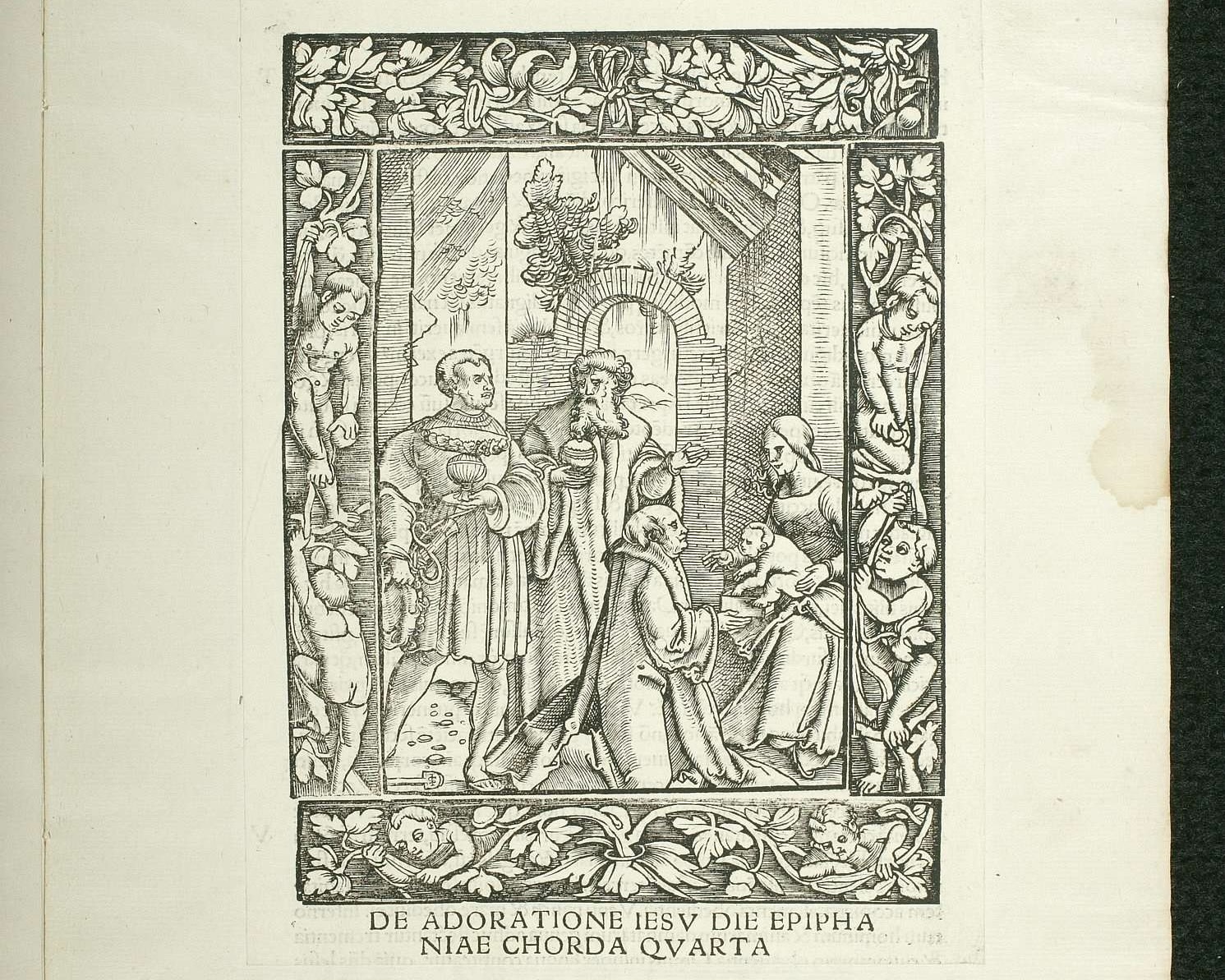

For example, a set of album pages that once belonged to a single collector contains (among other, unidentified works) woodcuts published by French publisher François Gryphius in the book Novum Testamentum Illustratum insignium rerum simulachris (1540). Other album pages contain work by another French artist, Bernard Salomon (also known as Le Petit Bernard), created for the book Figures du Nouveau Testament (1559). The fluidity of his linework and drama of his composition marks him as an artist balanced between the Renaissance and French mannerism.

There are also fragments of a less literal type in the collection.

Many of the artists have known histories—their names, where they were born and where they died, where they worked. Others are known to us only as incomplete names, usually a surname. Some artists, though they might have created fairly well known works, have names that have been lost entirely.

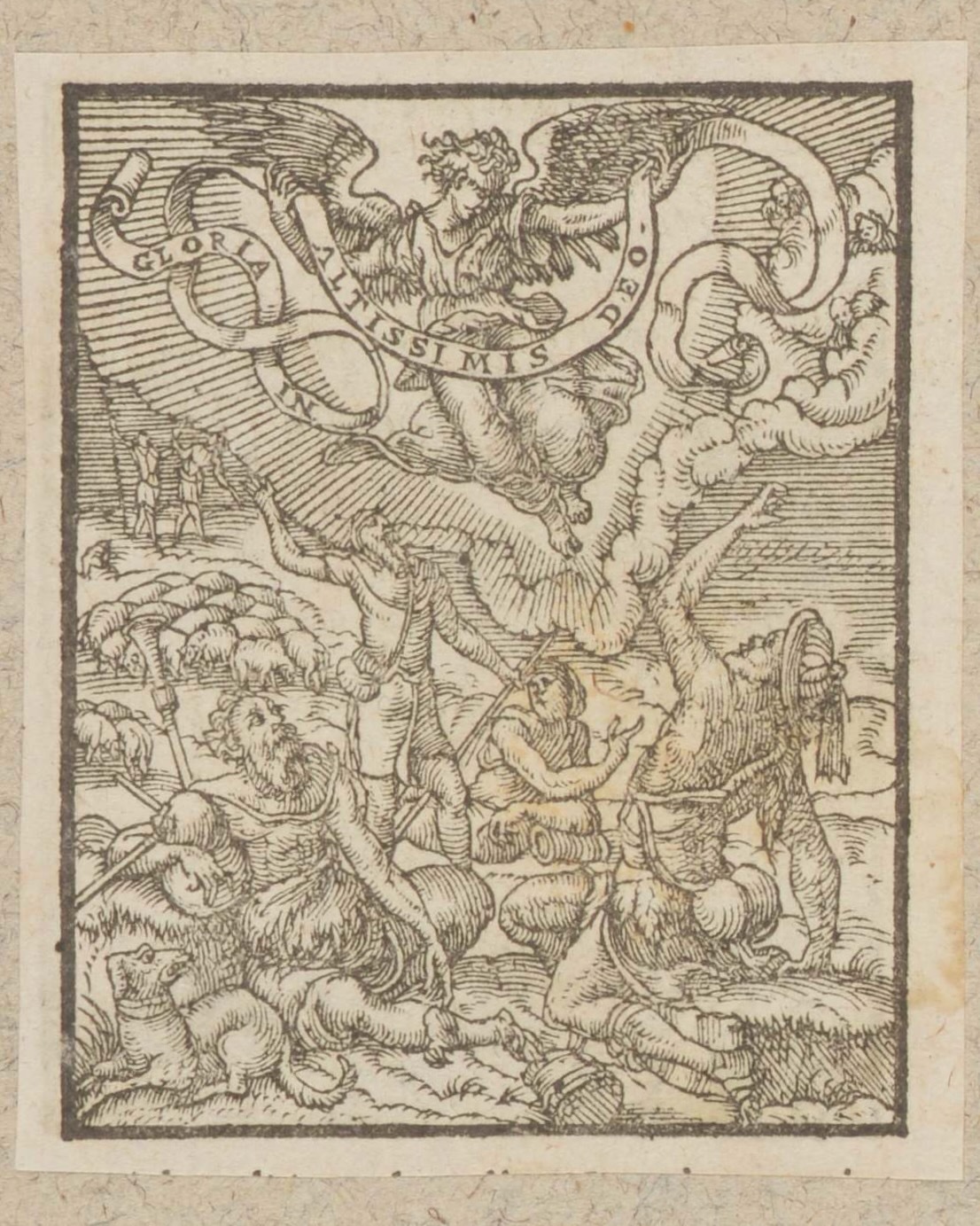

One artist, who created the central images in a series of woodcuts for the 1517 book Decachordum Christianum (fragments AAP5413 02–AAP5413 11), has been assigned a name by art historians. Since his signature contains a tiny shovel pictogram and the initials “I.S”, he is known as Monogrammist I.S. mit der Schaufel (or Monogrammist I.S. with the Shovel).

One woodcut fragment in the collection is especially unusual. Like the other woodcut fragments, The Virgin in Glory (AAP0085) is a small work, about 11 centimeters in length. The work is professional, although it doesn’t come near the skill shown by masters like Albrecht Dürer or well-known woodcut illustrators like Bernard Salomon. The lines are uniformly thick. The style is Classical, with solemn faces and hooded eyes inspired more by the Renaissance than by the populism of Reformation-era imagery.

Some of the saints that surround the Virgin and the infant Christ are depicted with symbols that aid in their identification, often referring to legends or histories of the saint’s life. St. John the Evangelist appears on the left, with a tiny snake emerging from his chalice. St. Peter stands next to him, holding a pair of large keys. St. Stephen appears first in line on the right, holding a martyr’s palm with the stones of his martyrdom suspended in his halo. The saint standing behind him, who seems to hold two arrows, is probably St. Sebastian.

What makes this woodcut unusual is that it is signed with a full name, something that is seen in very few woodcut illustrations of the 15th–16th century. Below the image, text proclaims “DANIEL LIECHTENSTEIN FINXIT” asserting, in Latin, “DANIEL LIECHTENSTEIN MADE THIS.” Liechtenstein was not a master of the woodcut and may not have been a professional artist. He seems to have been fairly unknown even during his lifetime.

The artist’s signature also indicates exactly which European artistic circle produced this woodcut. Daniel Liechtenstein worked with his relative, Petrus Liechtenstein, a member of Venice’s book and print publishing community. By the 16th century, Venice was a dominant force in the European publishing world and Petrus Liechtenstein (originally from Germany) had worked in Venice since the late 15th century.

With the who and where established for this fragment, we turn to another question: from what book was this woodcut removed? Petrus Liechtenstein was prolific, but Daniel Liechtenstein was not. Historical evidence suggests that Daniel only worked on one book: Officium Beatae Mariae Virginis, printed in 1545 by Petrus’s publishing house.

Often it is possible to confirm the origin of a fragment like this through finding a copy of its book, either through online repositories like HMML or through contacting a library or museum that has a print copy. With Officium Beatae Mariae Virginis, there seem to be no known publicly available copies; the latest reference to one, that I could find, is in 1914, when it was written about by Victor Masséna in his Etudes Sur L'art de la Gravure Sur Bois À Venise.

Masséna’s book, like a few other sources, states that Daniel Liechtenstein only produced three woodcuts for Officium Beatae Mariae Virginis. Only one of those three woodcuts—listed by Masséna as Vierge (La Ste.) glorifée (The Virgin in Glory)—is identified by subject and title. It seems that the woodcut is not only a fragment of a book, but a fragment of a book that is nearly lost.