Medieval Fragments In The Palazzo Falson

Medieval Fragments in the Palazzo Falson

This story is part of an ongoing series of editorials in which HMML curators and catalogers examine how specific themes appear across HMML’s digital collections. From the Malta collection, Dr. Daniel K. Gullo shares this story about Fragments.

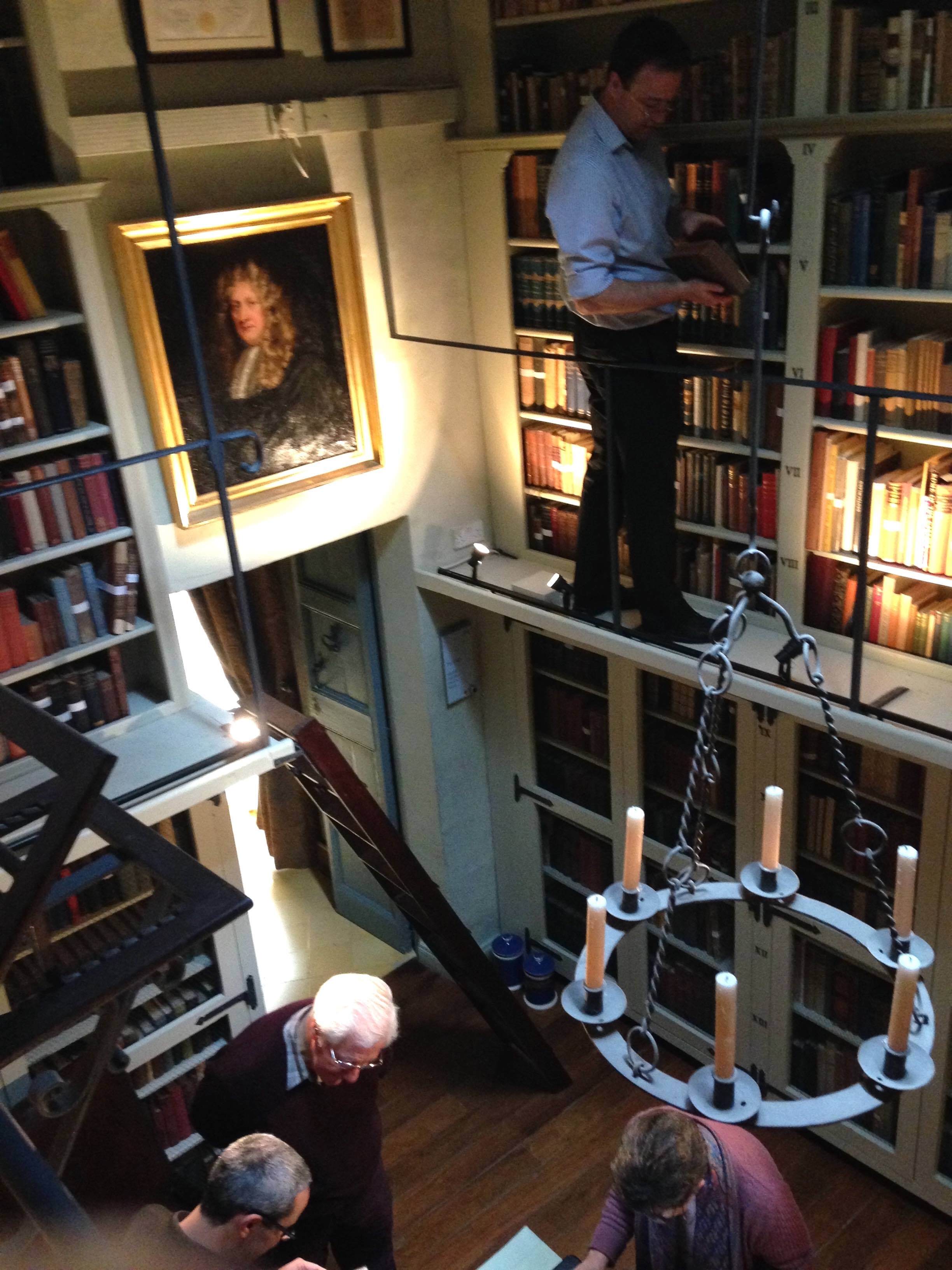

When I arrived at the Palazzo Falson in Mdina, Malta, in 2014, I recognized an opportunity to digitize a small but important collection of archival, print, and manuscript material related to Malta and the Order of Saint John of Jerusalem.

The Palazzo Falson’s collection originated with Captain Olof Frederick Gollcher (1889–1962), the son of a prosperous shipping merchant of Swedish descent. Gollcher was a leading figure in the arts and cultural circles in Malta and Italy, as well as an artist, scholar, and philanthropist in his own right. Gollcher was truly a discerning collector of objets d'art and historical objects. His library included several thousand books and manuscripts. After agreeing to digitize the collection, Francesca Balzan, curator of the Palazzo Falson at the time, helped me identify the manuscripts and rare Melitensia (materials related to the study of Malta).

While surveying the library we found many early modern books that preserved their original bindings. As library sleuths might know, these original bindings sometimes hold hidden manuscript fragments, often used to add support when binding the printed book. We knew that if we could find fragments within these original bindings, it would be of great value to the library and its readers.

Ms. Balzan, the staff, and I thus began a search for fragment treasures in the books’ bindings. After a few hours, our search began to yield those precious gems. In some instances, we found charter documents used as binding waste to support the sewing of the book block. Others were smaller, hard-to-identify manuscripts. Later in the day, we found large, medieval manuscript fragments bound within two early printed books. Today, we’ll take a closer look those two large manuscript fragments and the mysteries therein.

Medieval Fragment #1

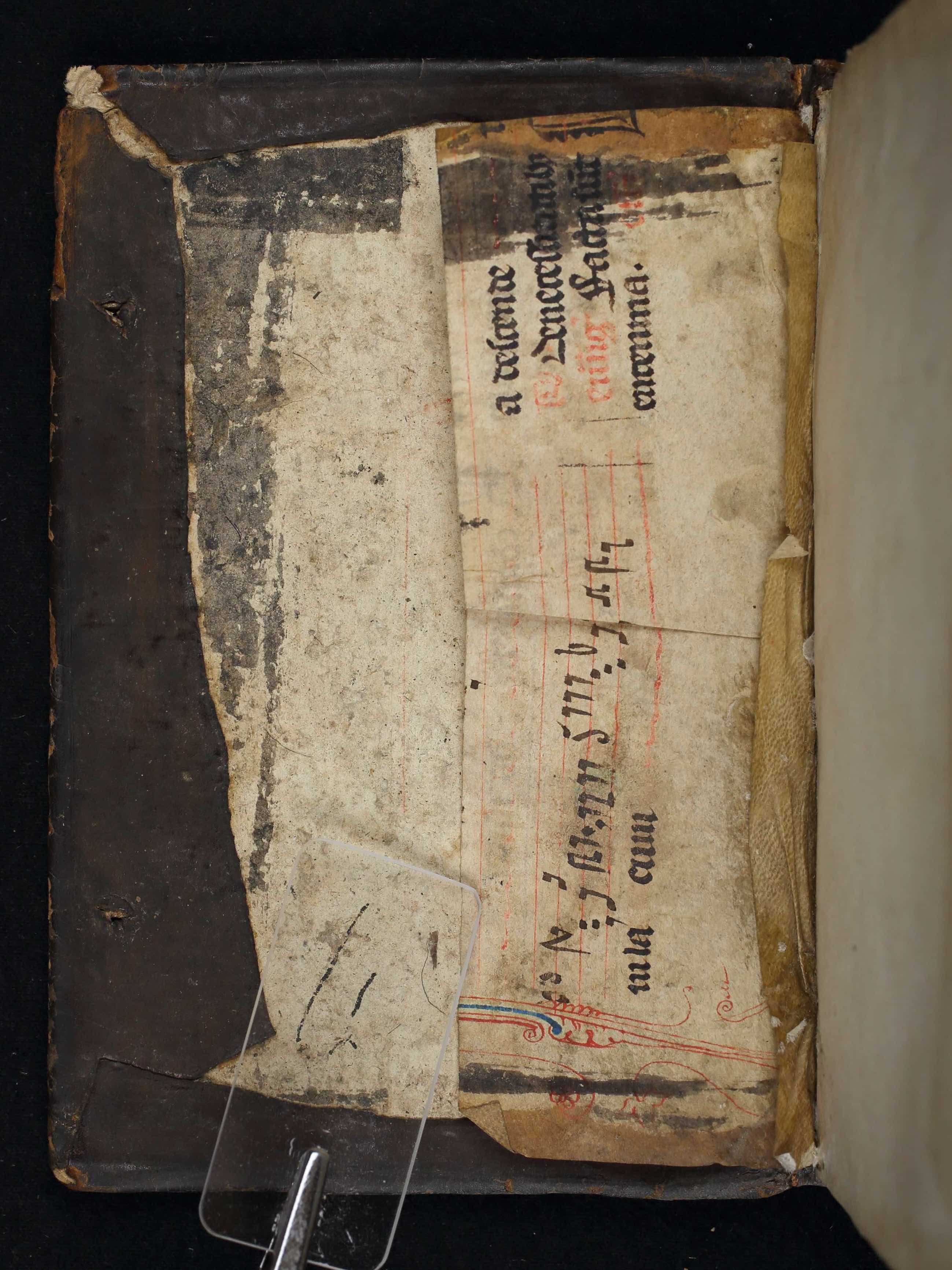

The first large, medieval fragment was found in PFL 00010 (shelfmark H - B 3970), a 16th-century volume containing two works by Jean Royaerds, published by Joannes Steels in Antwerp in 1538: the Homiliae per festivitates sanctorum and Homiliae in omnes epistolas dominicales juxta literam.

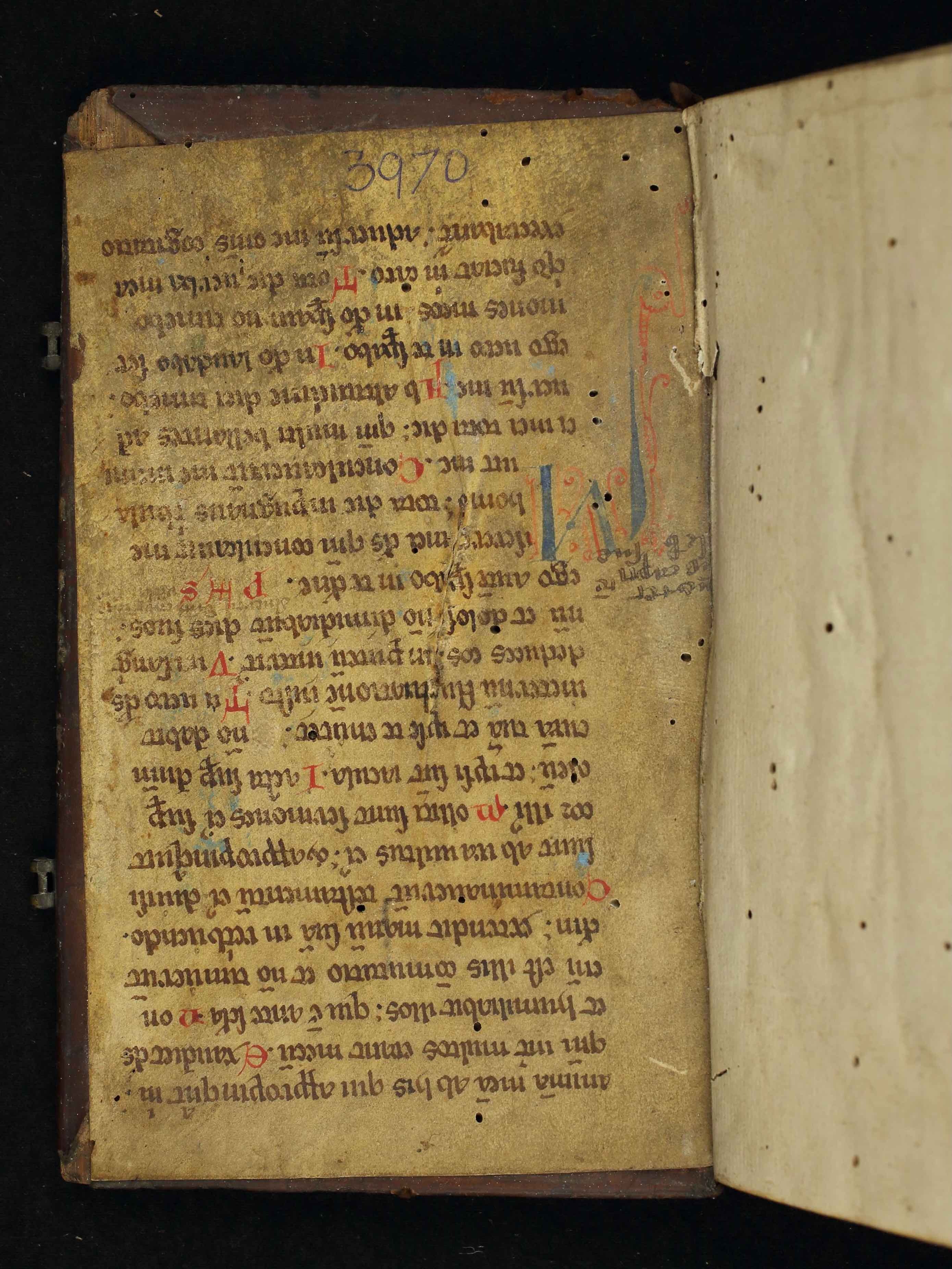

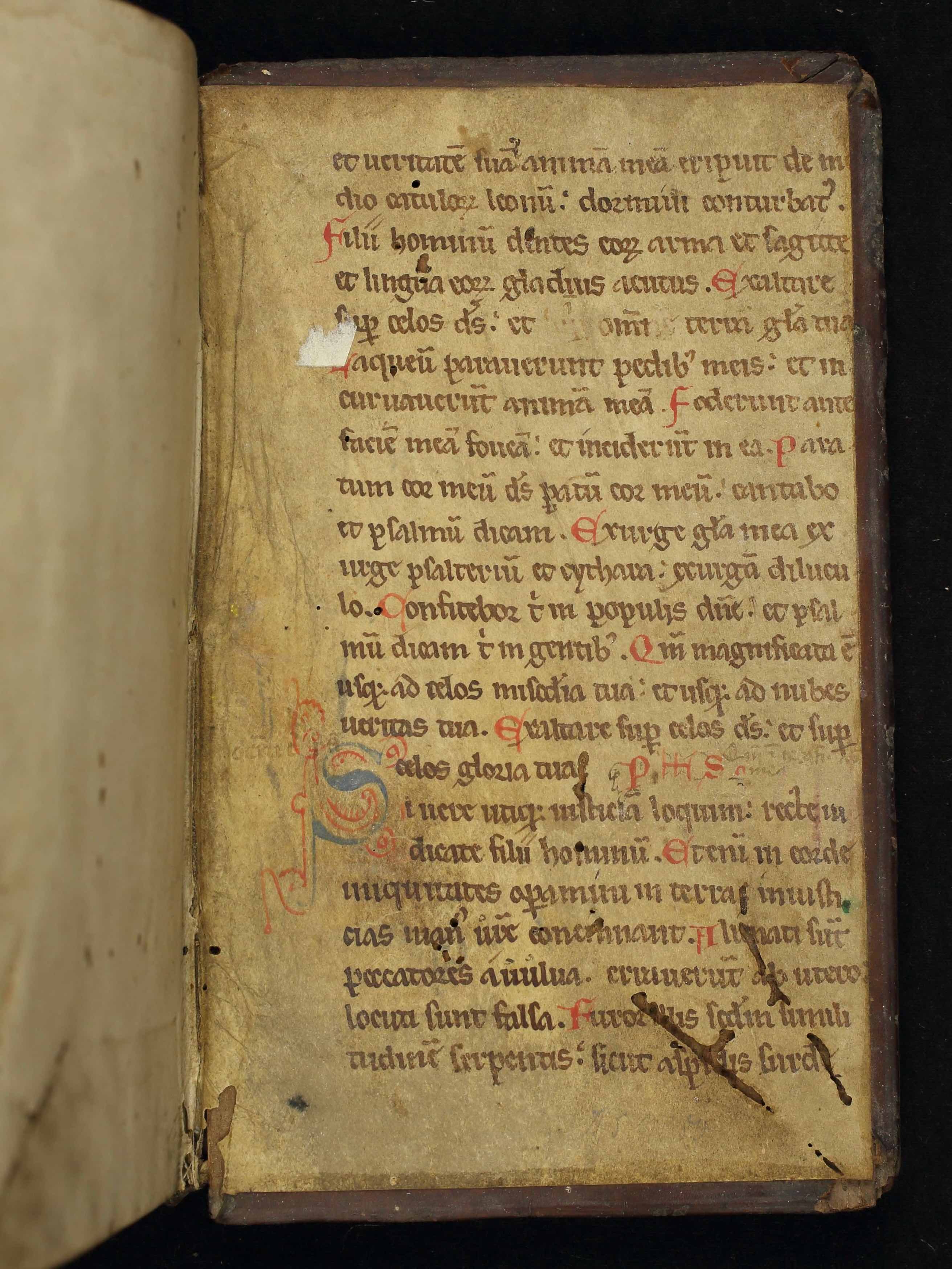

The person who bound the book in the 16th-century used dismembered manuscript leaves as pastedowns on the inside of the front and rear covers (the boards). Pastedowns were often used to conceal channeling, pegging, and other mechanics of the binding, as well as to protect these crucial binding elements from damage.

Inside the front cover, the first leaf was pasted upside down, demonstrating its utilitarian purpose (since it wasn’t applied with ease of reading in mind). In the upper center of the pastedown, which is the bottom of the fragment, one can see incomplete information about the current shelfmark (“3970”), written relatively recently with a dark blue ballpoint pen.

The two leaves used as pastedowns came from the same medieval Psalter. This text was written on parchment with black ink, likely in Northern Europe (Belgium, France, or the Netherlands) during the 13th or 14th century. The text was written in one column with 23 lines per page. Two three-line decorated initials in blue and red penwork mark the beginning of a new psalm, showing the care taken to produce a work that was to be enjoyed as well as read for study and prayer. Minor capital letters in rubrics were used to mark the beginning of a new line in the Psalm.

The text of the front inside pastedown begins partway through Psalm 54, line 19—“animam meam ab his qui appropinquant mihi…”—and ends with Psalm 55, line 6: “tota die uerba mea execrabantur; aduersum me omnes cogitatio[nes].” The text on the rear inside cover begins with Psalm 56, line 4—“et ueritatem suam animam meam eriptuit de medio]…”—and ends with Psalm 57, line 5: “Furor illis secundum similitudinem serpentis ; sicut aspidis surde…” The textual continuity across the two fragments indicates that the two leaves came from consecutive folios within the Psalter, though they are now separated by two 16th-century printed works.

Medieval Fragment #2

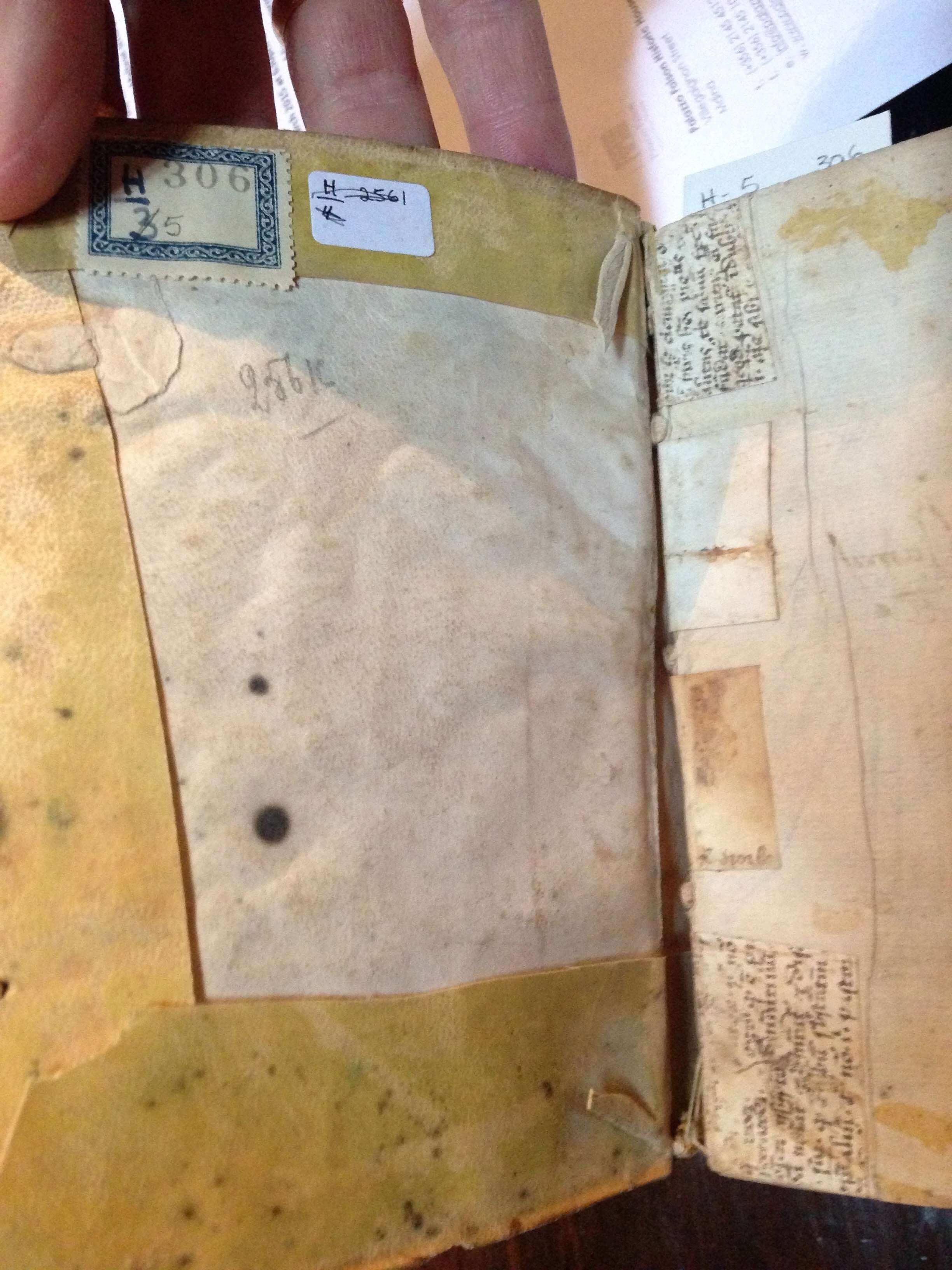

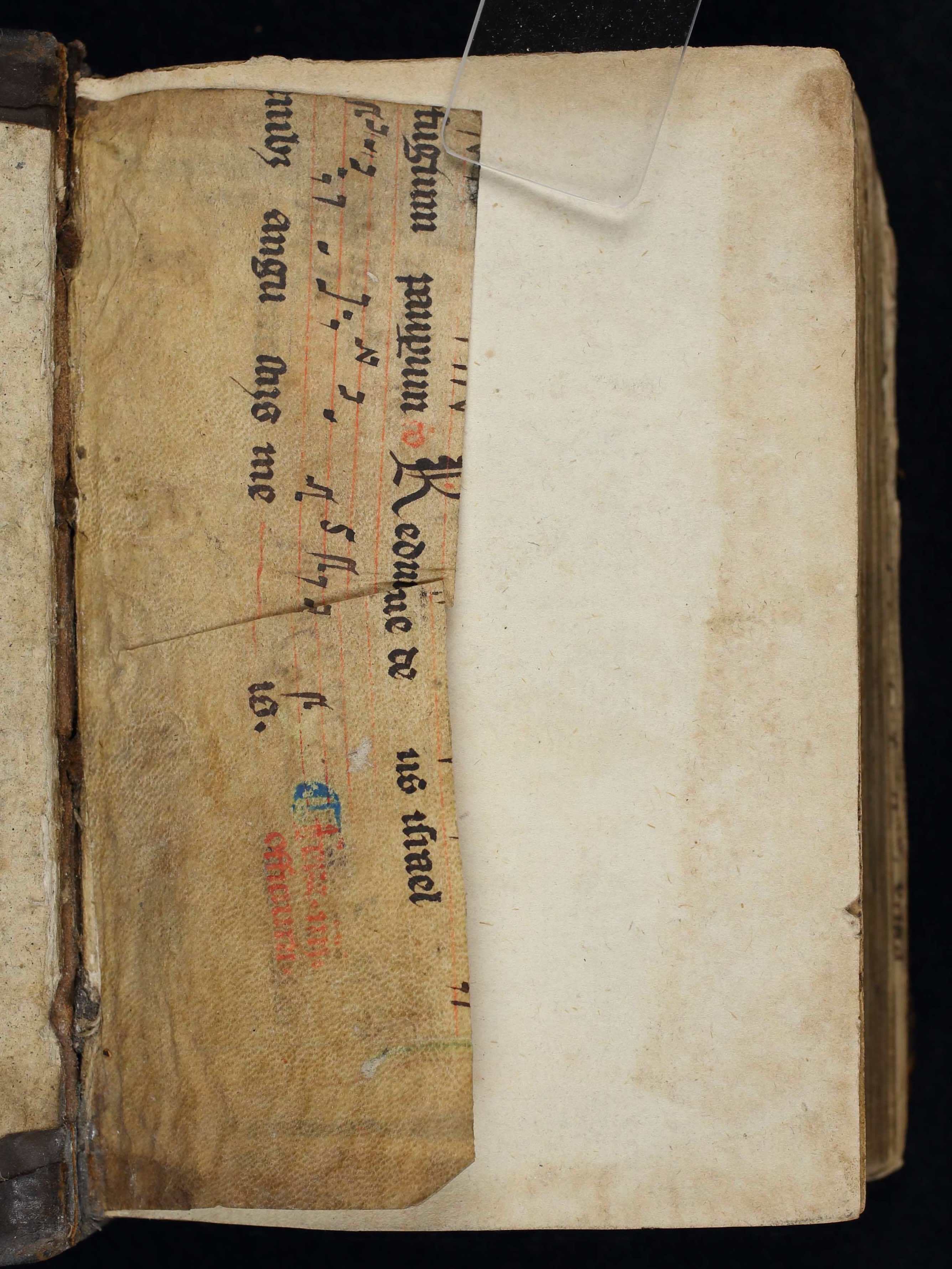

The second large fragment was found in PFL 00008 (shelfmark E - 7 4092), a volume containing a Latin edition of the New Testament that was edited and translated by Erasmus of Rotterdam and printed by Merten de Keyser in Antwerp in 1535.

The binder of this volume decided to use the medieval fragment as a partial flyleaf near the rear cover, serving as an extra layer of protection for the printed New Testament text in the event of damage to the binding. Though the manuscript fragment does not cover the complete page, the area close to the gutter of the book, where most of the wear from opening and closing would occur, is given extra strength by being reinforced with the parchment fragment.

Liturgical text with music cover both sides of the flyleaf, so I thought the fragment might have come from a medieval Missal. To confirm my hypotheses about the flyleaf’s text and origin, I contacted Dr. Debra Lacoste, Dr. Jennifer Bain, and Dr. Anna Huiberdina Hilda de Bakker, who manage and contribute to Cantus, a database for Latin Ecclesiastical Chant.

They agreed that the fragment came from a Missal, but they suggested a date earlier than I expected. Dr. de Bakker clarified that the parchment fragment was likely written in England, during the early 13th century. She noted that the inclusion of the offertory verse “refugium pauperum” localizes it within typical English missals, and the melody matches those found in the Sarum concordances (developed at Salisbury Cathedral in England). An English provenance is also indicated by the inclusion of an s-like neume (a note or group of notes sung to a single syllable, from the Greek word pneuma, meaning “breath”).

Dr. de Bakker added that the fragment is bound backwards, with the verso actually being the recto.

Small Item, Big Impact

The identification of these fragments demonstrates how a digitization project provides an opportunity to reinvestigate a collection, often leading to discoveries of previously unknown objects. In the case of the Palazzo Falson, finding these fragments increased the value of the collection, and sharing our knowledge of their existence contributes to evidence about the dissemination of medieval music and the reuse of medieval music manuscript fragments as binding material in early modern Europe.