Johann Wetzstein And The Qurʼan Fragments Of Tübingen

Johann Wetzstein and the Qurʼan Fragments of Tübingen

This story is part of an ongoing series of editorials in which HMML curators and catalogers examine how specific themes appear across HMML’s digital collections. From the Western European collection, Dr. Josh Mugler shares this story about Fragments.

Johann Gottfried Wetzstein (1815–1905), a native of Saxony, served as honorary Prussian consul in Damascus, Syria, from 1849 to 1861. While in Damascus, Wetzstein looked for additional sources of income; he made some profit from agricultural investments in southern Syria, but he also found success in collecting manuscripts and selling them to German libraries. Nearly 3,000 manuscripts from Ottoman Damascus are now located in libraries in Berlin, Leipzig, and Tübingen as a result of Wetzstein’s business.

For Wetzstein, the work was lucrative, but it was not always easy. The people of Damascus were well aware that their cultural heritage was being exported at an alarming rate. In a report on his collections, Wetzstein alludes to this, writing, “The learned Mohammedan sees with deep pain that the only means of teaching himself and his children the old Humanities is disappearing from view.”

Wetzstein’s neighbors disapproved of selling manuscripts to Europeans and made it difficult for him to find willing trading partners. He eventually found a dealer named Aḥmad, nicknamed “the Egyptian camel” (al-Jamal al-Miṣrī) because of the bag of books that was usually on his back. Aḥmad would typically visit Wetzstein after dark. In his writing, Wetzstein refers to this sort of trade relationship by quoting a lament of Maḥmūd Ḥamzah, a contemporary and prominent Muslim scholar of Damascus: “What can a person do against the power of money?”

One Collection Today

In the 1980s, HMML microfilmed the manuscript collection of the University of Tübingen in Germany. Among the library’s more than 1,950 manuscripts are 173 Arabic-script manuscripts collected by Wetzstein and sold to the university in 1864—the latest and smallest of the four collections that he exported to Germany.

The Tübingen-Wetzstein manuscripts are almost all in Arabic, but there are portions in Persian and Turkish, two manuscripts in Kurdish, and one, surprisingly, in Pashto (a language spoken primarily in modern Afghanistan, thousands of miles from Damascus. This is the first Pashto manuscript identified in HMML’s preservation photographs). Most of these manuscripts are from the Islamic tradition, but there are also a few texts by Christian and Druze authors. HMML’s copies remain on microfilm, but many of the manuscripts have since been digitized and can be viewed on Tübingen’s DigiTue website.

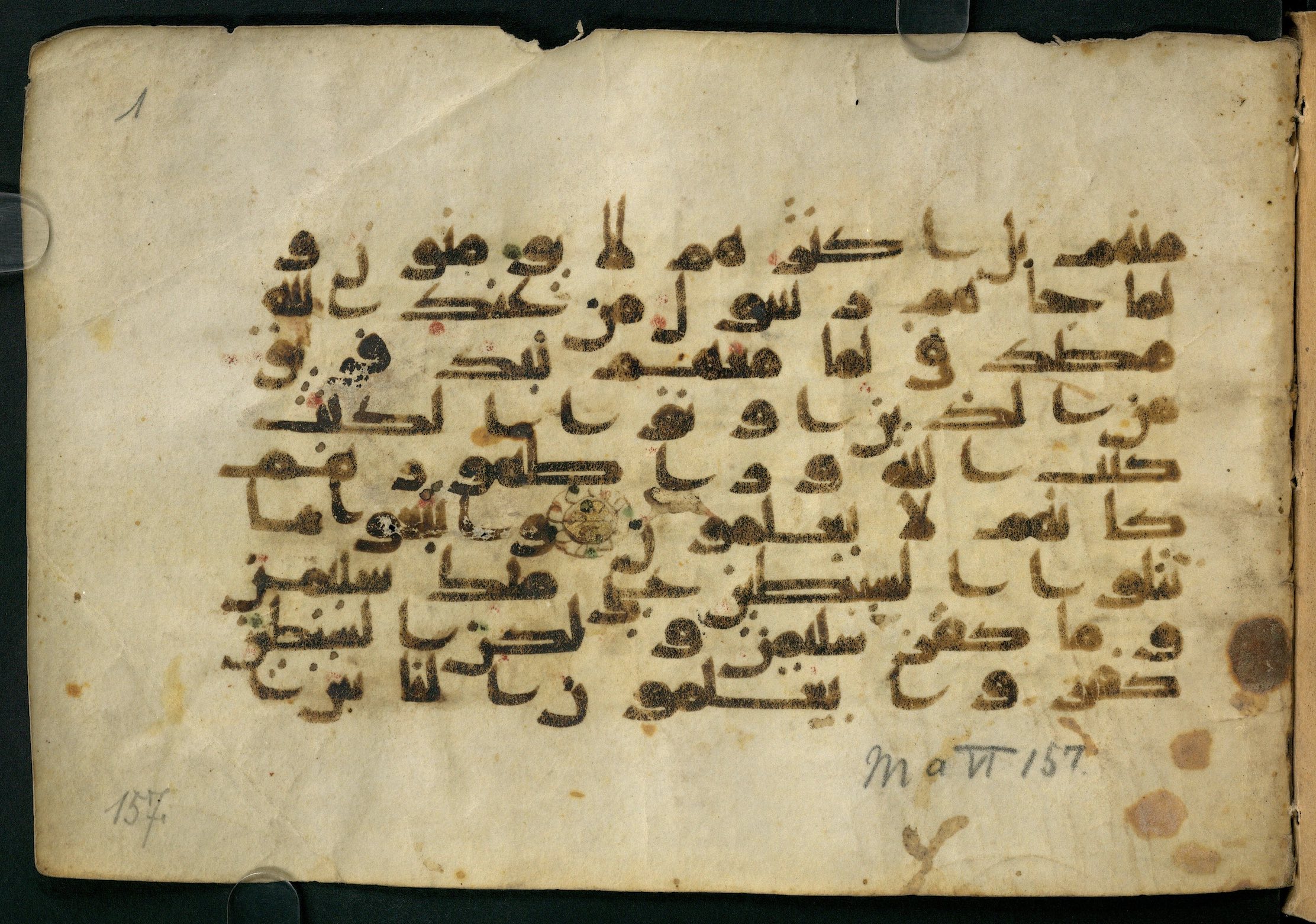

Wetzstein’s collecting decisions were shaped by the interests of European scholars, which included a search for the oldest manuscripts he could find. To that end, the Wetzstein manuscripts at the University of Tübingen include about 25 fragments of the Qurʼan that he called “Kufische Pergamente” (“Kufic parchments”). Paper replaced parchment for most manuscript purposes from an early date in Islamic history, so these parchment fragments are very old. The extent of each fragment ranges from a single leaf to more than 200 leaves, and almost all of them are written in the large “Kufic” script of early Qurʼan calligraphy.

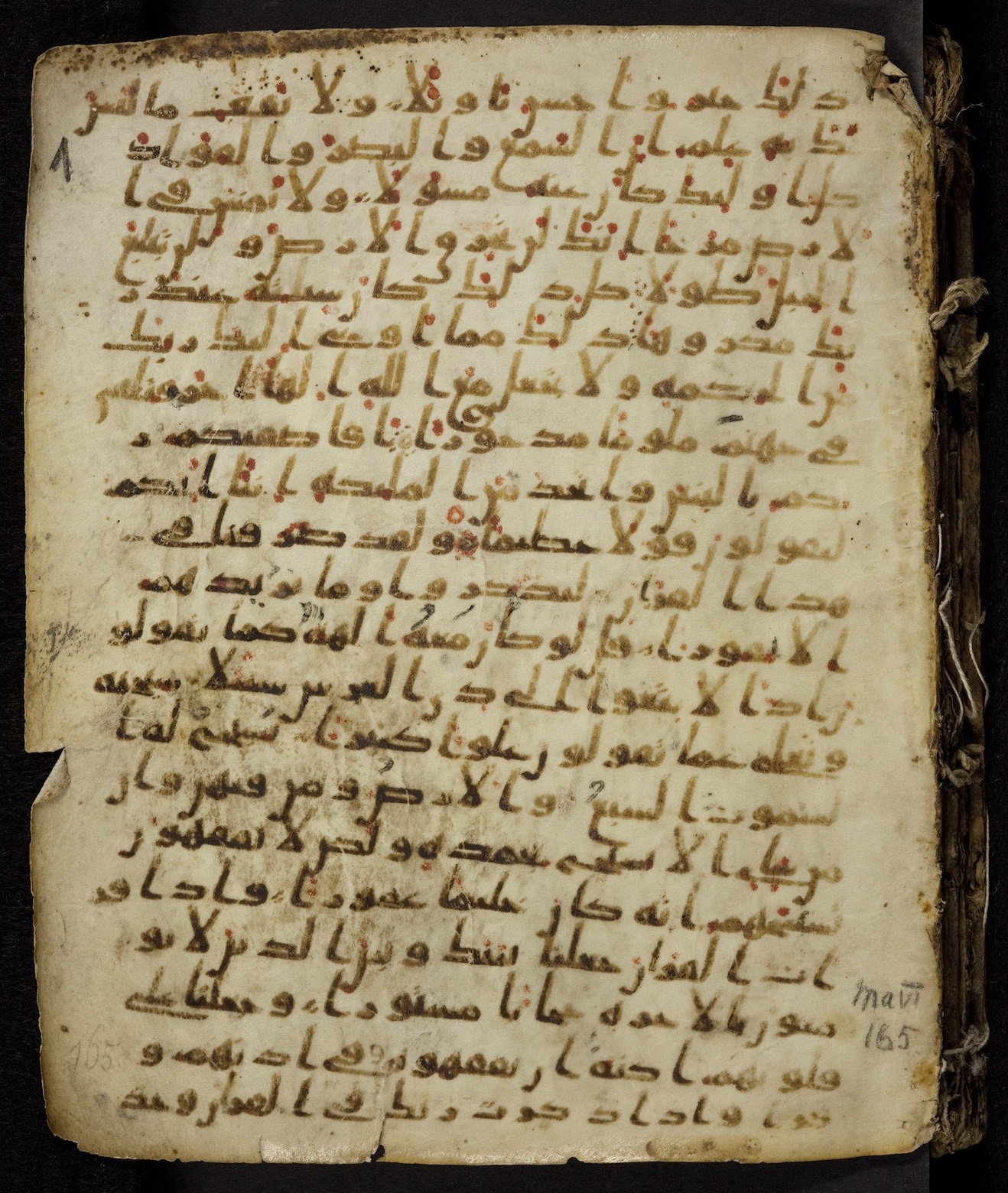

One fragment that stands out in this important collection is Ma VI 165 (HMML microfilm 42340), which includes 77 parchment leaves written in the even earlier Ḥijāzī script.

This manuscript has been radiocarbon dated between 649 and 675 CE with 95 percent probability, placing it within only a few decades of the prophet Muḥammad’s death. It is one of the oldest known Qurʼan manuscripts in the world. The significance of this manuscript has likely surpassed the wildest dreams of Wetzstein and the European scholars for whom he gathered these collections.

Further Reading:

Boris Liebrenz and Christoph Rauch, editors. Manuscripts, Politics and Oriental Studies: Life and Collections of Johann Gottfried Wetzstein (1815–1905) in Context. Leiden: Brill (2019).

Christoph Rauch, “Doppelflinten gegen seltene Manuskripte: Wie Wetzstein in Damaskus Handschriften erwarb,” in Alte Kataloge in neuem Gewand, Blog des DFG-Projekts Orient-Digital, February 18, 2022.

“Koran Manuscript from Early Period of Islam,” University of Tübingen, November 10, 2014.