Hiding In The Binding — Fragments In Rare Book Collections At HMML

Hiding in the Binding — Fragments in Rare Book Collections at HMML

This story is part of an ongoing series of editorials in which HMML curators and catalogers examine how specific themes appear across HMML’s digital collections. From the Special Collections, Dr. Matthew Z. Heintzelman shares this story about Fragments.

Much of human history remains for us today only in the form of smaller remnants or fragments of larger works. Such bits and pieces sometimes provide important insights into the cultures we come from. The Oxford English Dictionary defines a fragment as “a part broken off or otherwise detached from a whole; a broken piece; a (comparatively) small, detached portion of anything.”

Over the past several years, interest in fragments has developed into a specialized area of manuscript studies called fragmentology, which even has its own dedicated journal (Fragmentology). In manuscript collections, a fragment is often thought of as a physical remnant of a manuscript that was once “whole.” But a text that is incomplete can also be considered a fragment of the whole text, even if the vessel itself (e.g., the book) is physically intact. Manuscript or book collections, too, can be fragmented and dispersed across different locations or among different owners.

HMML has photographed hundreds of thousands of manuscript fragments since its first library partnerships in 1965.

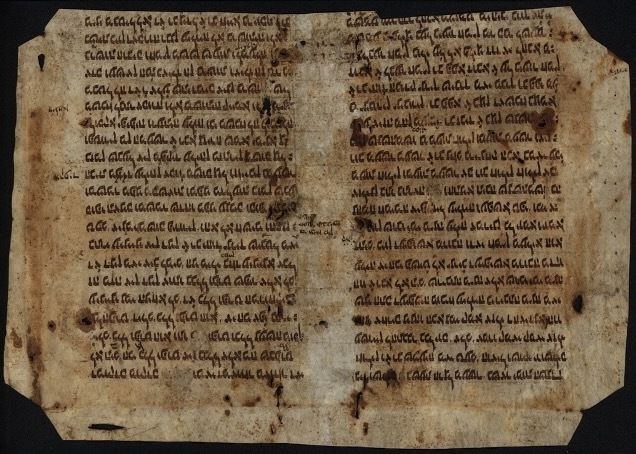

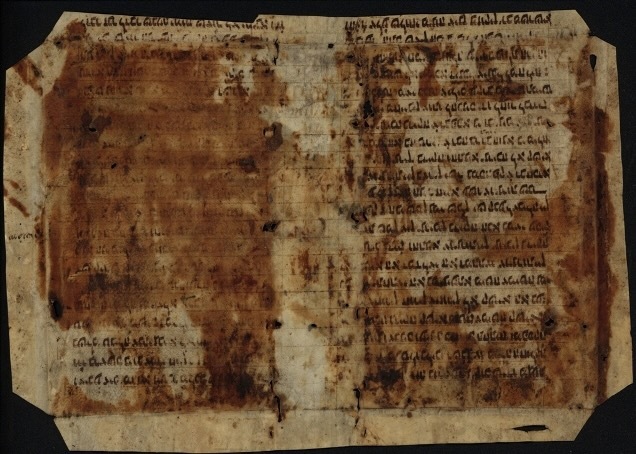

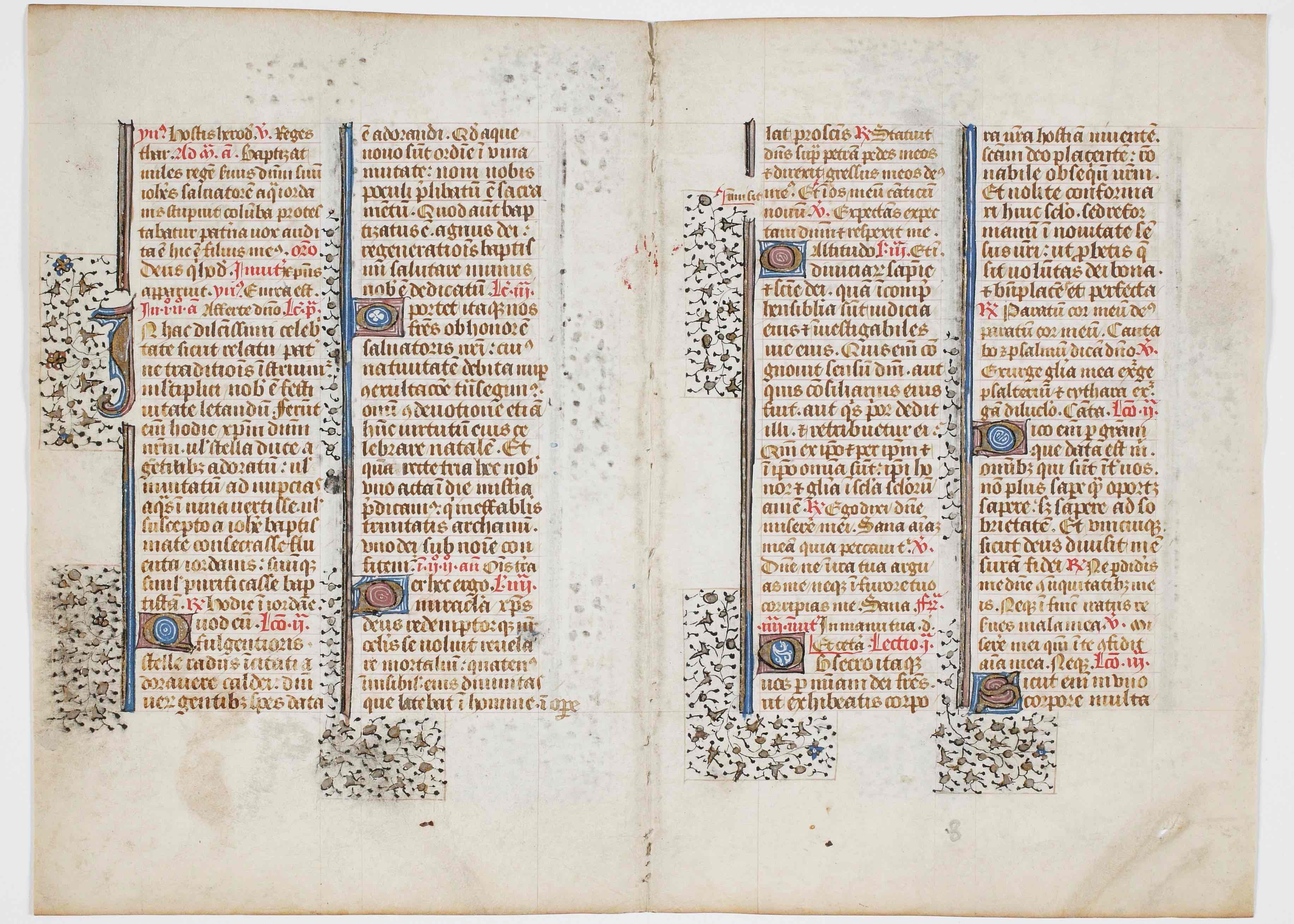

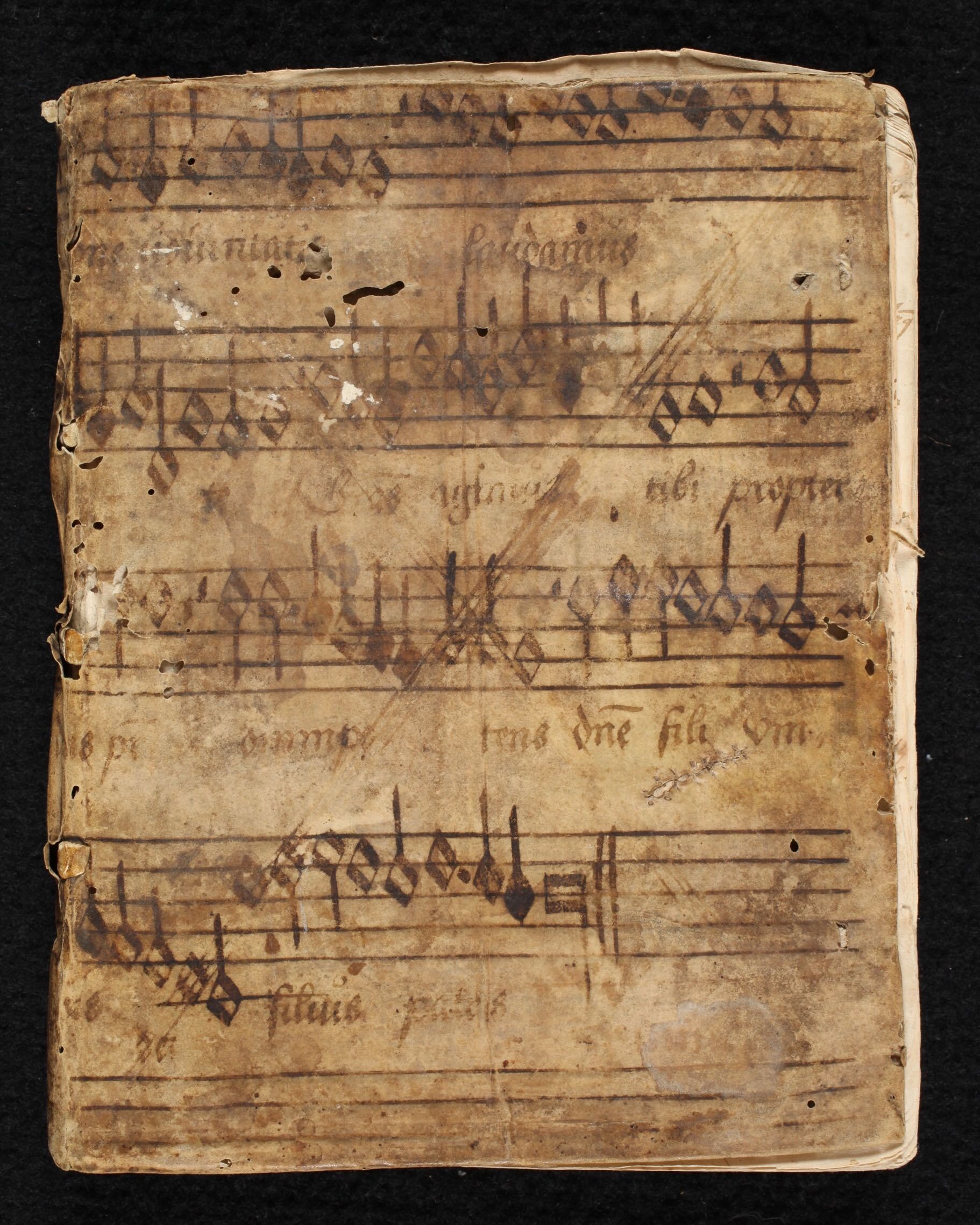

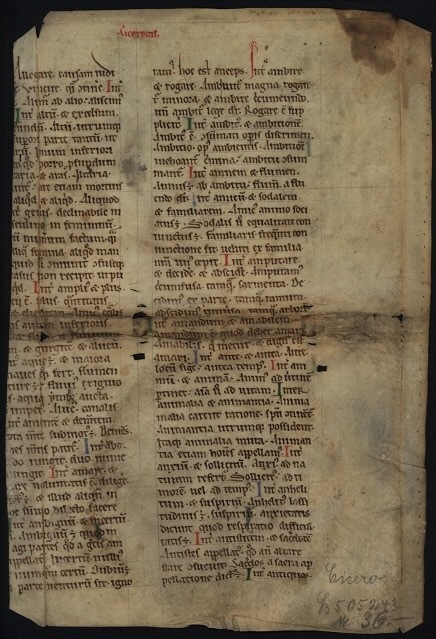

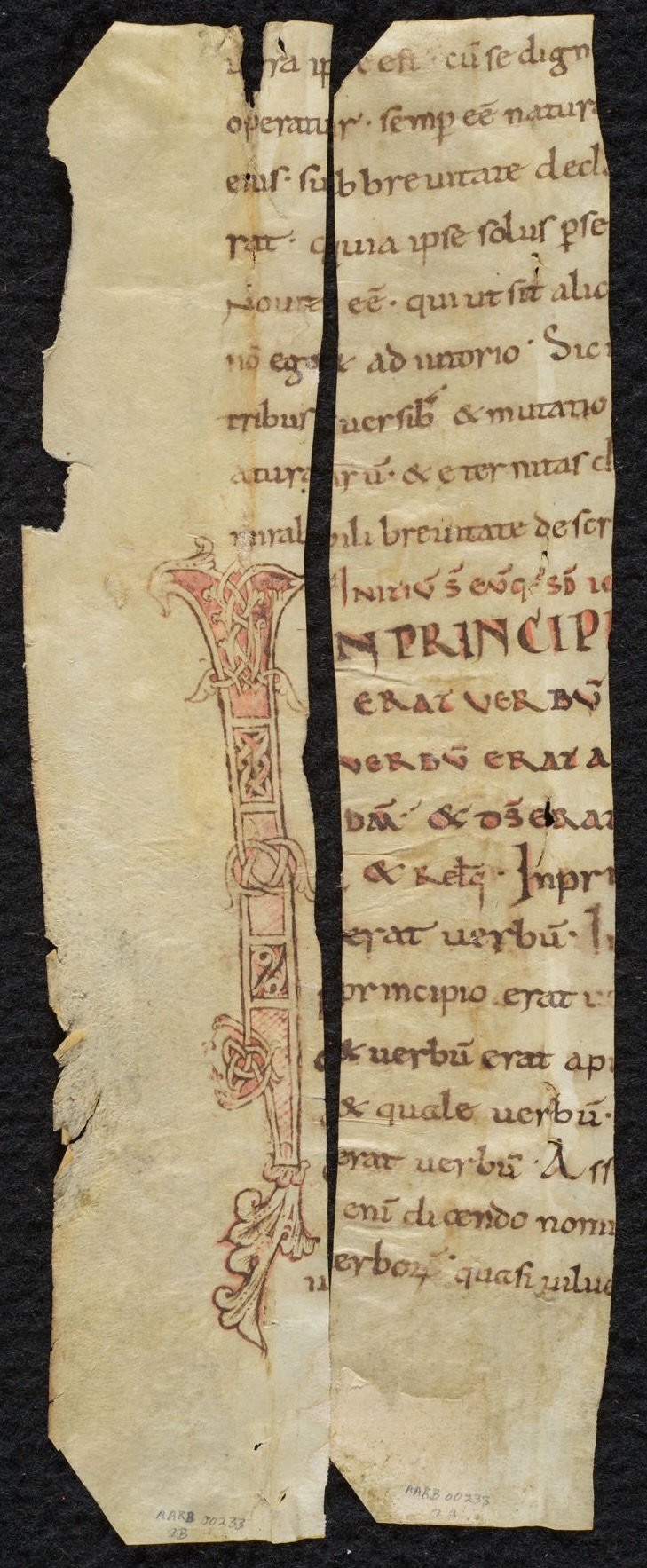

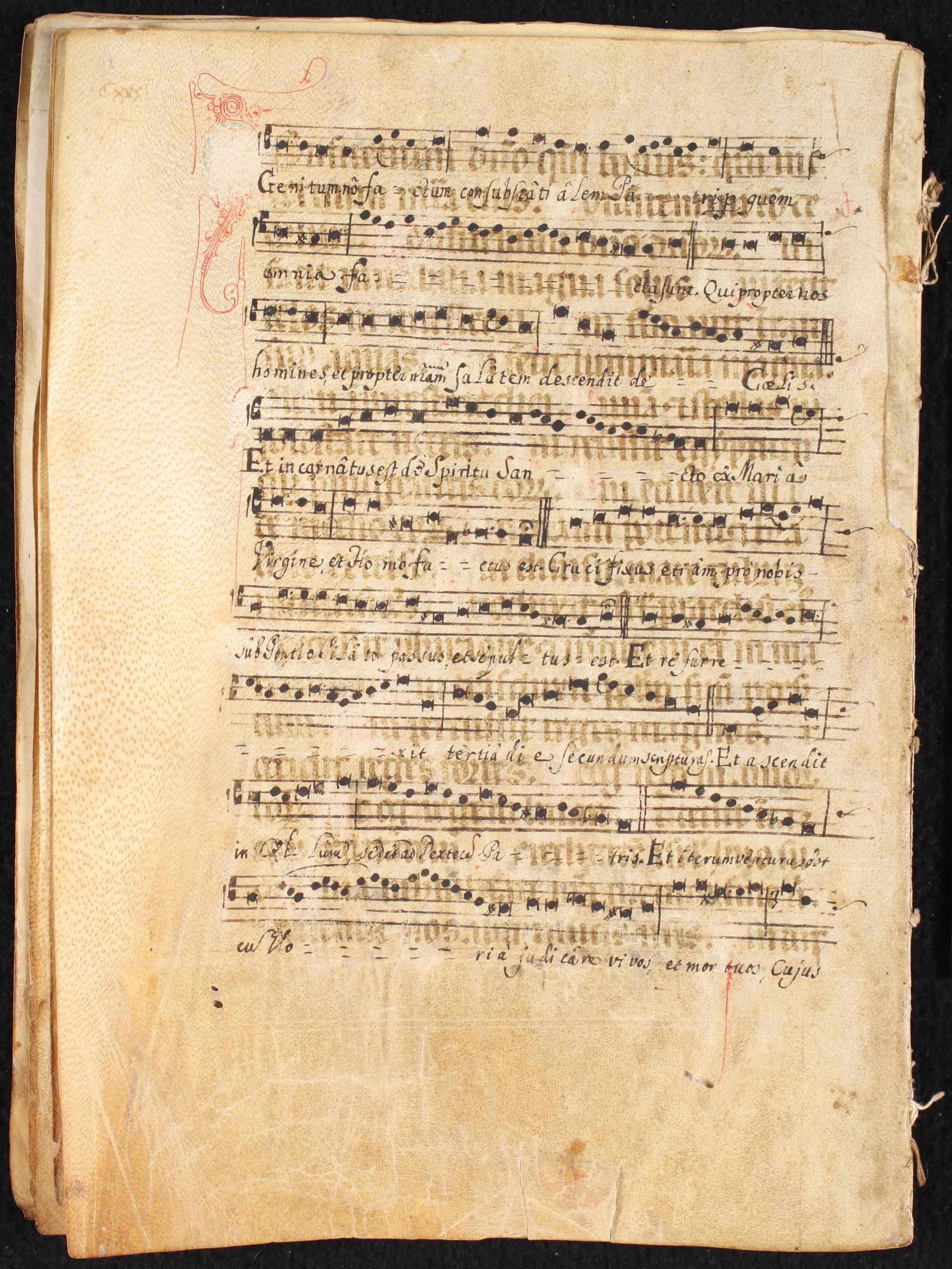

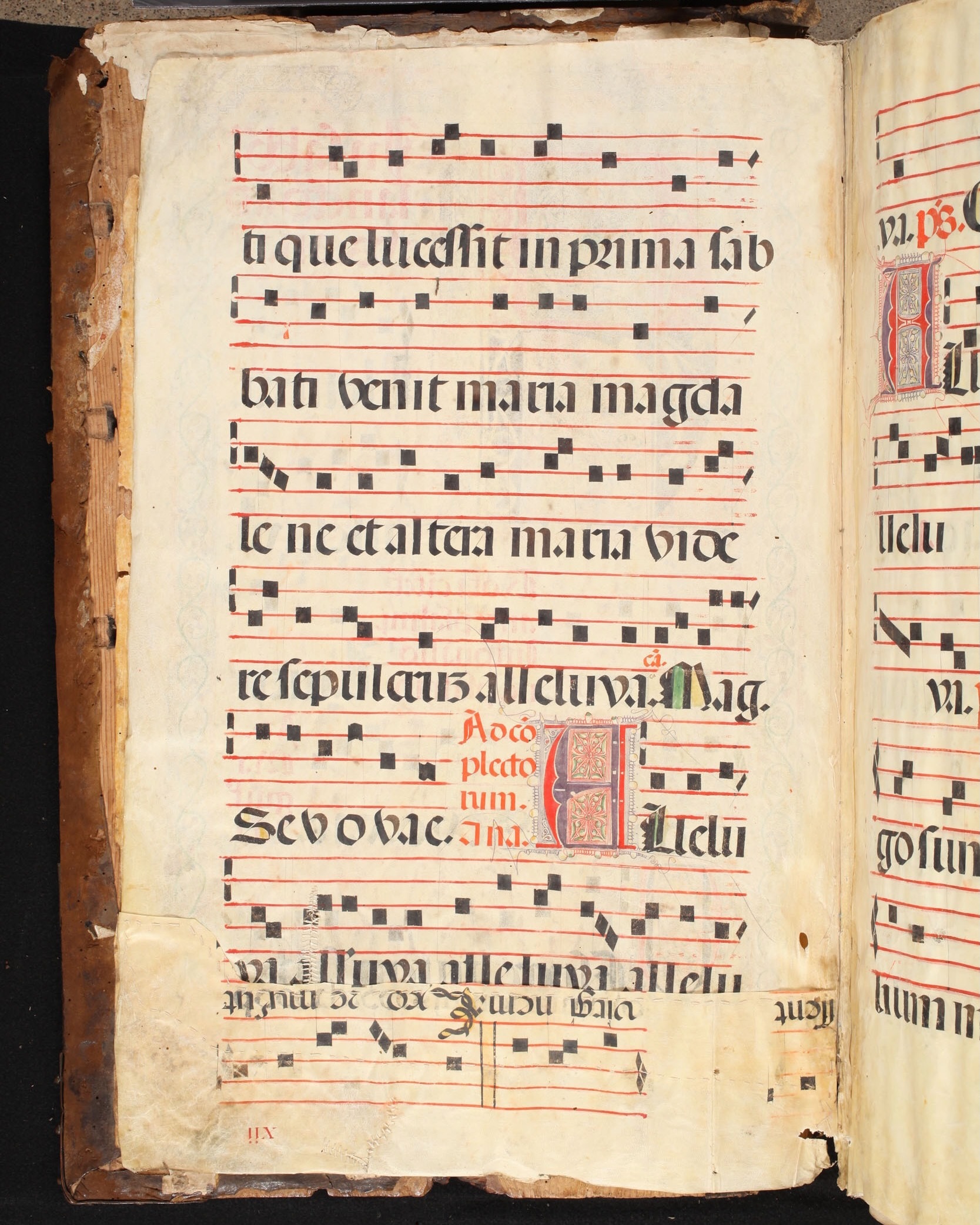

In the collections of HMML, the Malta Study Center, and Saint John’s University—all located at HMML in Collegeville, Minnesota—there are more than 100 manuscript fragments (and many more printed fragments), most of which are now viewable in HMML Reading Room. Their diversity makes them extremely useful for teaching about manuscripts, languages, and scripts. The materials are chiefly in Latin, but also include many items in Arabic, Coptic, Ethiopic, Persian, German, Hebrew, Dutch, Armenian, and Syriac. Some have musical notation or marginal glosses. They range in size from about 3.5 inches (9 cm) tall to more than 30 inches (76 cm) tall. The oldest is about 1,500 years old, while the newest might be from the 18th century. Some are drab and others are stunningly beautiful. And several remain hidden in the bindings of other manuscripts or printed books!

Becoming a Fragment

Manuscripts can become fragmented for many reasons. The most common means is through decay and destruction—for example, due to war, fire, water, aging, neglect, etc. A contributing factor can be when the material from which a manuscript is made is itself fragile or contains inks or adhesives that are corrosive.

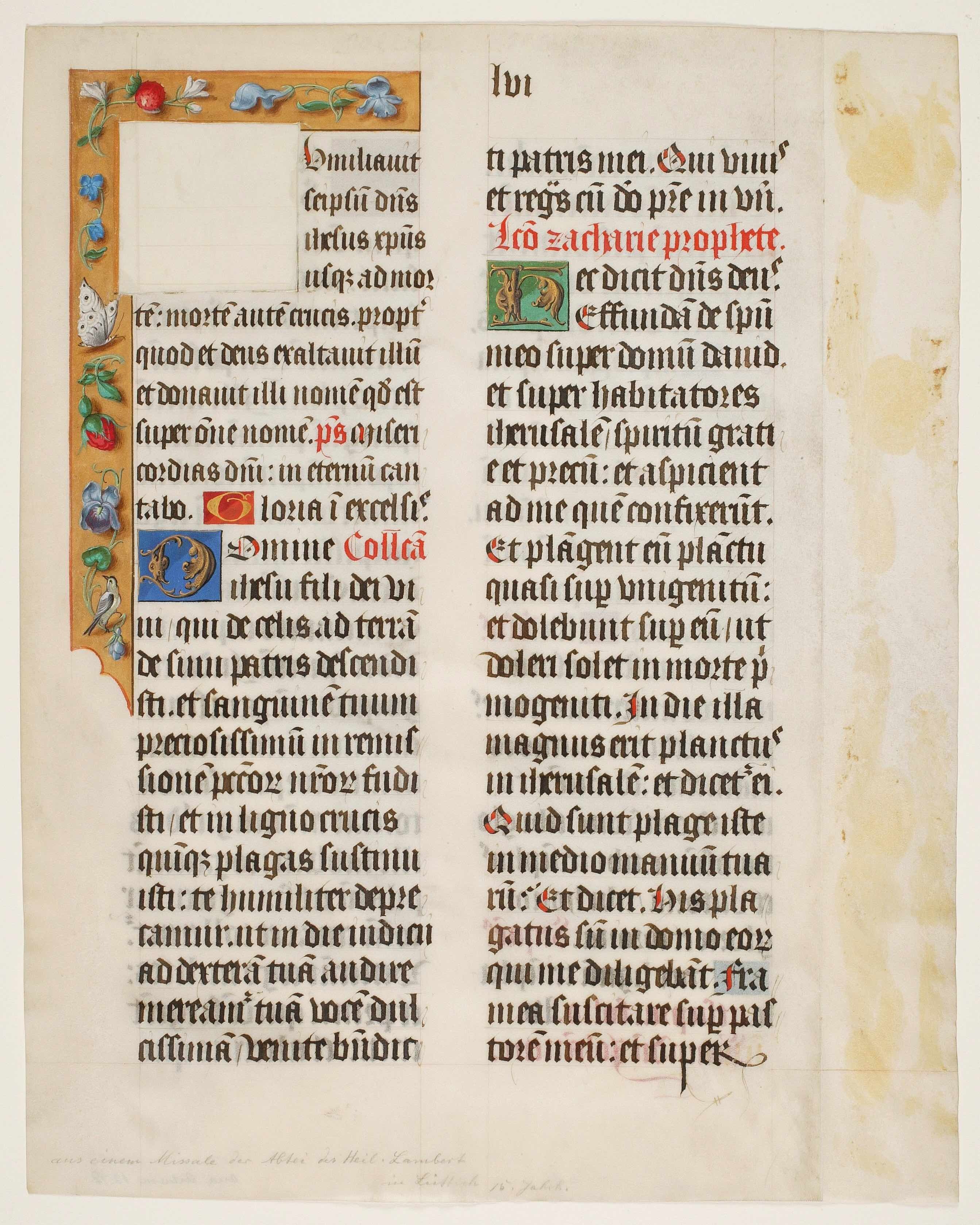

Sometimes manuscripts fall prey to people who wish to isolate the prettiest parts, and thus they excise or cut out the beautiful miniatures and illuminated or elaborately decorated initials.

Some modern dealers of rare materials have engaged in the practice of “breaking” books—cutting out the pages and selling or distributing them separately. The most famous of these book-breakers was Otto Ege (1888–1951), but there have been many others. Several manuscript fragments in the Arca Artium collection come from broken books.

However, one could argue that the greatest loss of manuscripts has been through the reuse or “recycling” of old leaves, especially ones made of durable parchment. This usually happened when the contents of the manuscript were no longer current or were not of interest to later audiences. The reusing of leaves took many forms:

- Book covers

- Pastedowns

- Flyleaves

- Stubs, used to hold in extra pages

- Folded pieces to reinforce gatherings or quires

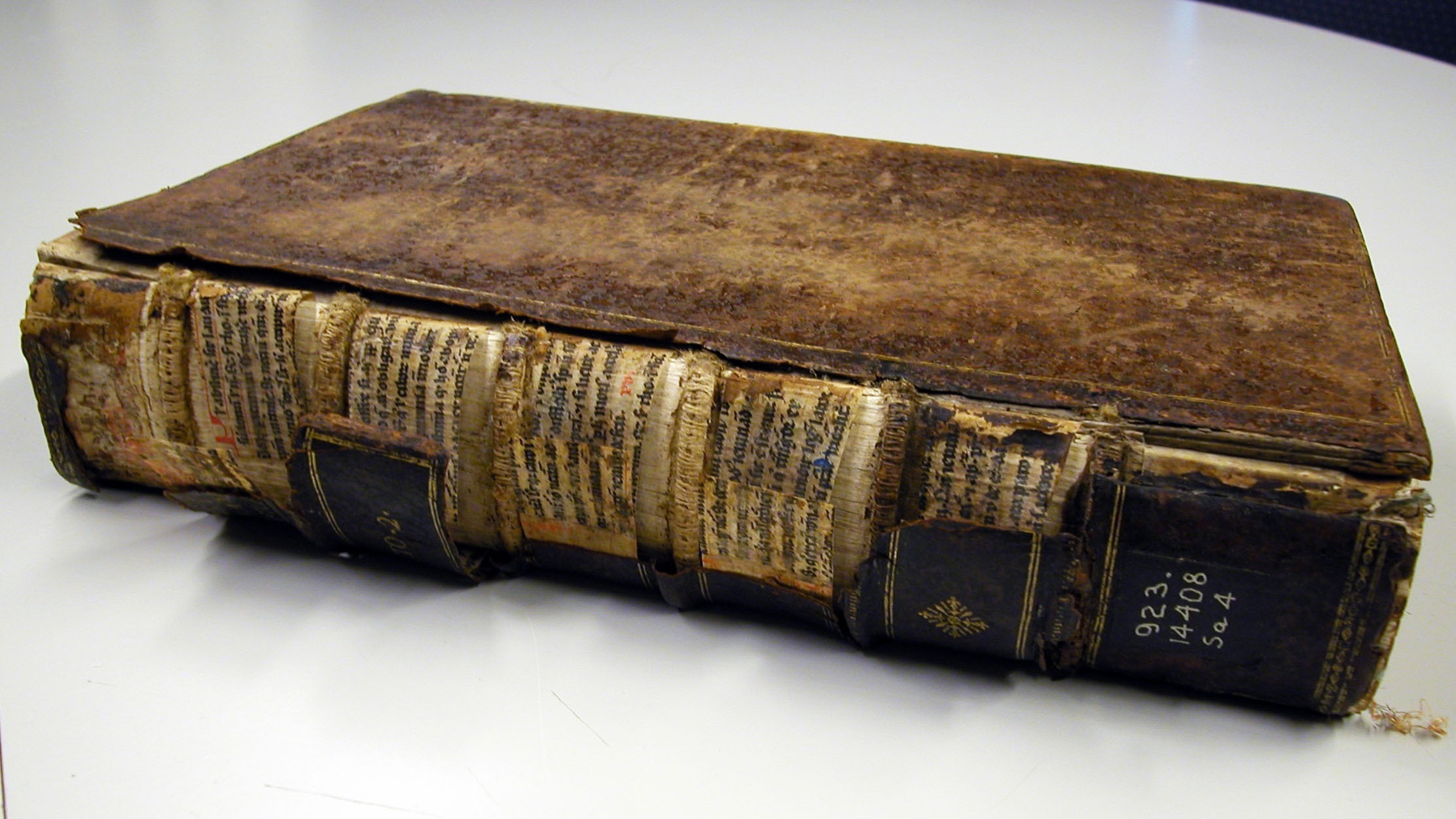

- Strips to reinforce spines

- Palimpsests—for example, HMML 00654

- Repairs to damaged leaves

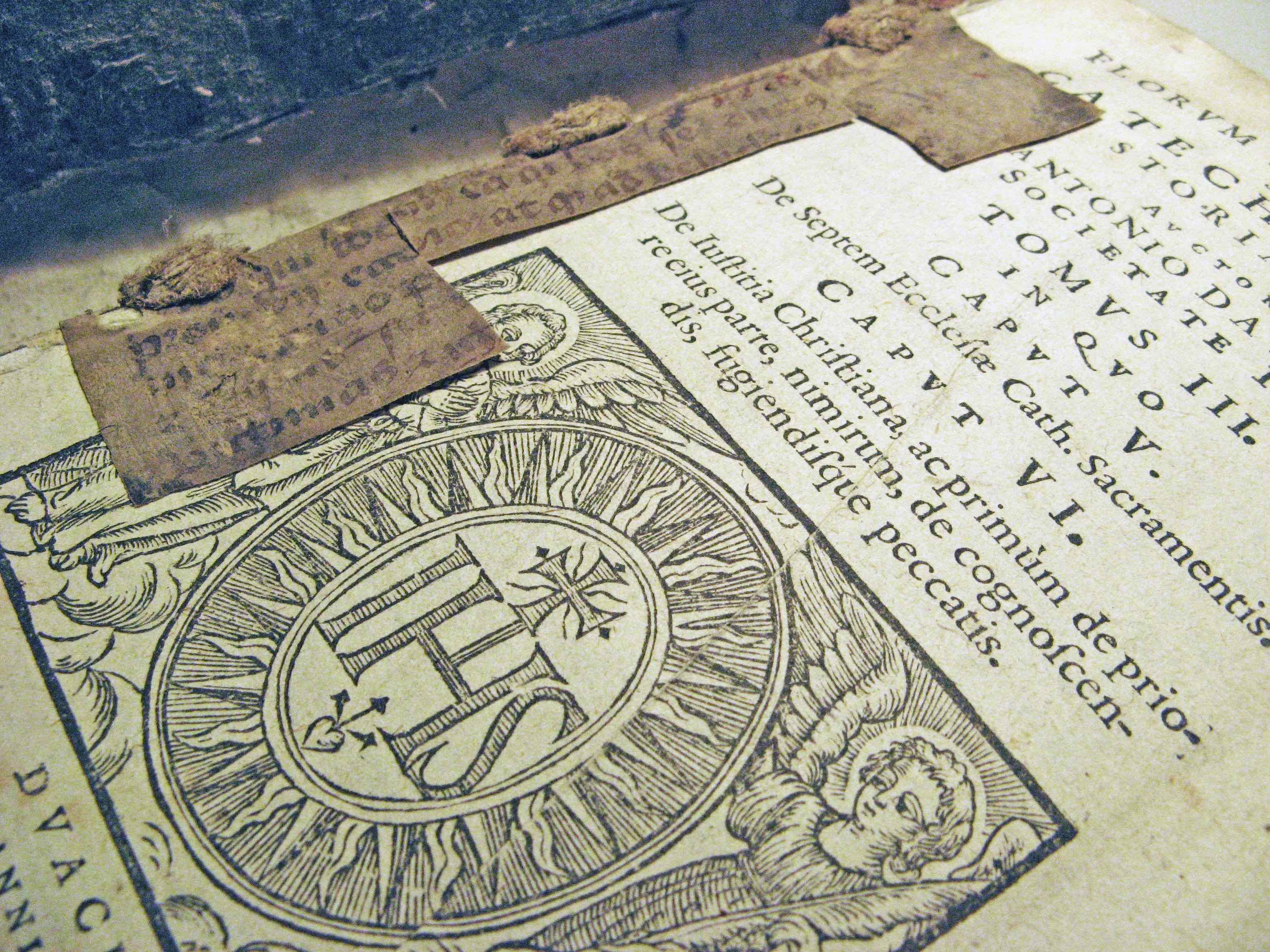

What follows is a gallery of fragments that have been recycled through the centuries, to show some of the ways that bits and pieces of manuscripts now appear in HMML’s Special Collections.

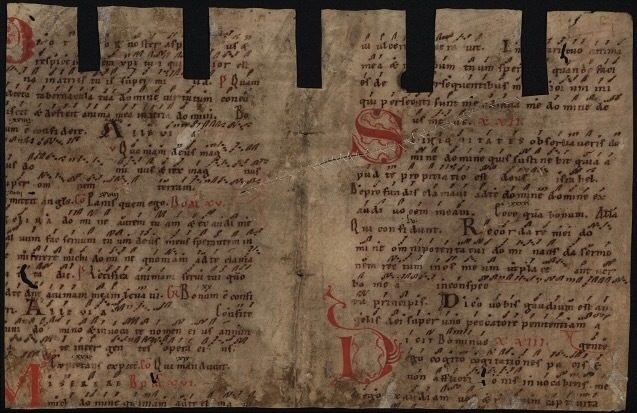

Book covers

One of the most common ways to reuse parchment leaves is as the actual cover of another book.

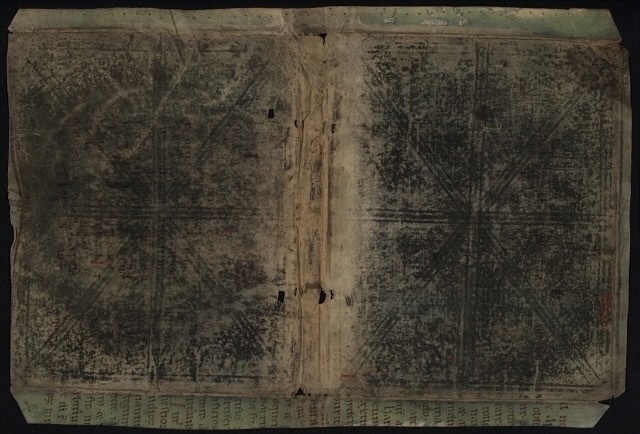

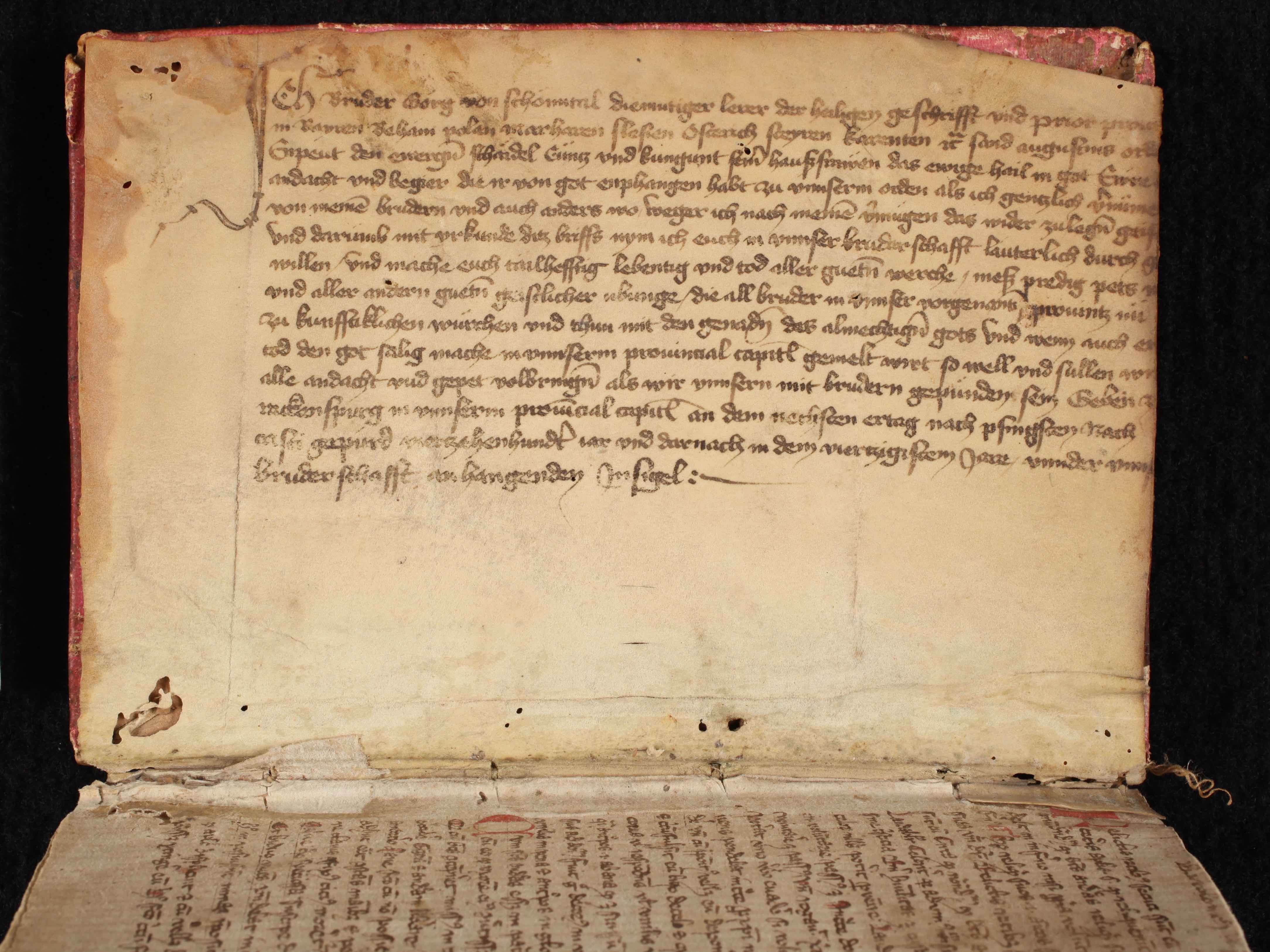

Pastedowns

A pastedown is the sheet glued into the front and/or back cover of a book; it helps to hide the elements that hold the book together. If one uses a strong material like parchment, the pastedown can also provide further stability to the binding.

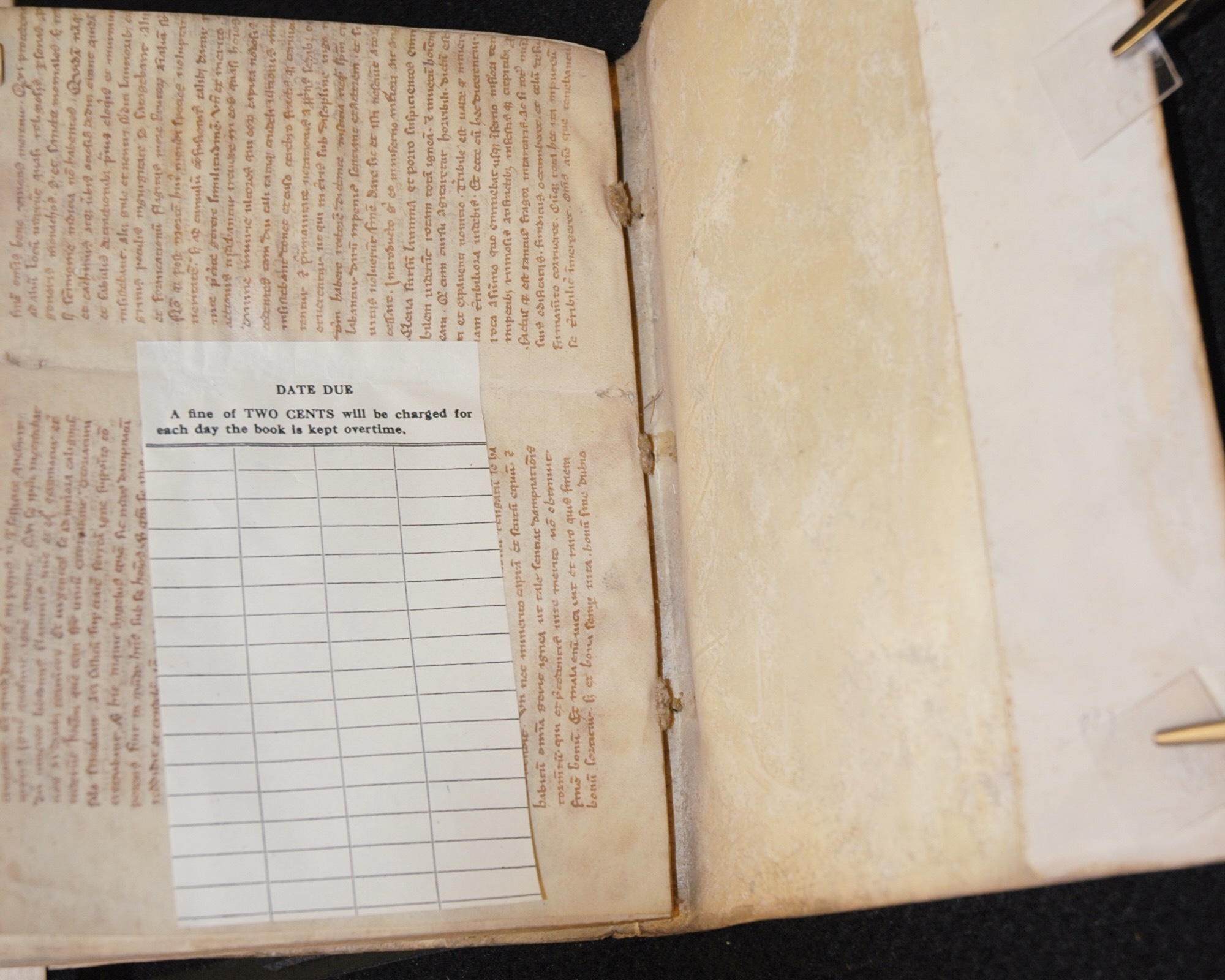

Flyleaves

Flyleaves are used at the front and back of a book to protect the main text and to make the binding stronger. In the era of hand-bound books, they were often recycled from parchment manuscripts.

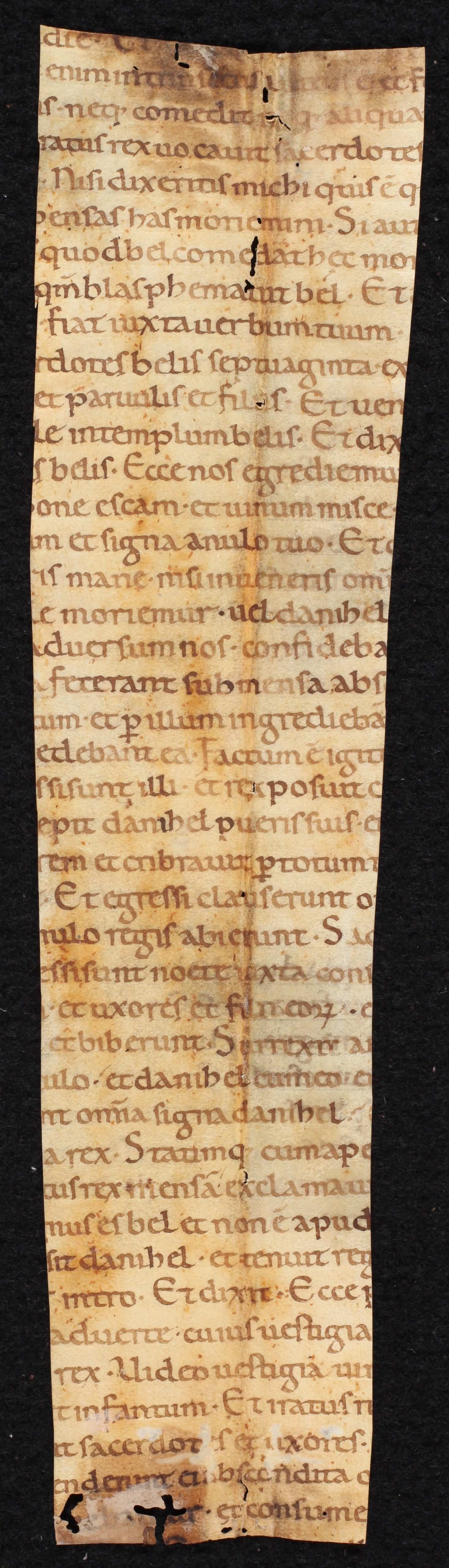

Folded Pieces to Reinforce Gatherings or Quires

Often, parchment manuscripts were cut into little strips or stubs to provide strength, especially when binding paper pages. If these are still in the book, they may only appear as small stubs along the gutter of the page openings; should they be removed from the binding, their previous use can be identified by the crease passing anomalously through the text. In other cases, such strips of parchment may be glued into the back of a book to strengthen the gatherings along the spine.

Other Examples: Palimpsests, Repairs, and…a Lampshade (?)

Due to its durability, parchment will often outlive the usefulness of its contents. Sometimes, later generations have simply washed or scraped off the old ink (and text) and written a new text over it. Sometimes, a more valued manuscript is held together with pieces of a manuscript that is no longer wanted. And sometimes, the manuscript comes back in a completely different form that might surprise us.

Want to see more manuscript fragments from the collections that HMML has photographed and cataloged? Go to HMML Reading Room and select “Fragments” from the “Genre/Form(s)” field in Advanced Search.

Oh, yes, and if you have clues that could help describe the fragments’ histories, please send us your suggestions!