Why Was Esau So Hungry? Genesis 25 In Arabic Manuscripts

Why was Esau so Hungry? Genesis 25 in Arabic Manuscripts

This story is part of an ongoing series of editorials in which HMML curators and catalogers examine how specific themes appear across HMML’s digital collections. From the Eastern Christian collection, Dr. Vevian Zaki shares a story about Food.

Among the well-known biblical narratives is that of the twins Jacob and Esau, and how the latter gave away his birthright privilege to the former (Genesis 25:29-34 NRSV). As the story goes, once when Jacob was cooking, Esau returned from a hunting trip feeling “famished” and asked Jacob to give him some of the stew he was making. Jacob allowed Esau some of it, but only on the condition that Jacob would receive his brother’s birthright. Essentially, Esau bargained away his birthright for a lentil stew and some bread.

Rather than focusing on the moral of the story, today we pose another question: why was Esau so hungry? Esau is described as a “skillful hunter, a man of the field” (Genesis 25:27 NRSV). He was also the favorite son of his father Isaac, who ate from and was fond of Esau’s game (Genesis 25:28 NRSV). Esau, then, was a tough man who was used to spending long periods in harsh conditions. However, he came home longing for and coveting what his twin was cooking. The narrative of Genesis describes Esau twice as “famished,” once in his own words (emphasis here my own):

“Once when Jacob was cooking a stew, Esau came in from the field, and he was famished. Esau said to Jacob, ‘Let me eat some of that red stuff, for I am famished!’”

(Genesis 25:29-35 NRSV)

HMML Reading Room has more than 35 manuscripts containing the Book of Genesis and related commentaries in the Arabic language, in both Arabic and Syriac scripts. I skimmed this story in various manuscripts in Arabic script. While Arabic manuscripts across the different traditions all stress the fact that Esau was suffering intense hunger or starvation, they vary significantly in the expressions, idioms, and sometimes in the phrases used to show his hunger. This diversity is understandable, since the Arabic Bible represents a confluence of several other biblical languages and traditions that were translated into Arabic. In the case of Genesis, this includes the Hebrew, Greek, Syriac, and Coptic languages.

As we shall see, the Arabic vocabulary used to express Esau’s hunger carries multiple connotations, not only of hunger, but also of exhaustion and distress. While the word jāʼiʻ would be the common adjective to describe a hungry man in the Arabic language, it seems that this alone was not enough to convey the meaning that translators of this passage into Arabic desired. So, they used stronger expressions or paired the word with other adjectives to amplify the sense of his hunger.

To give some examples, one version in a Coptic collection uses the word taʻbān, meaning exhausted (ABMQ 00003, page 70; and USJ 00419, page 28). Another Melkite Greek Orthodox text (OBC 00246, folio 246v) describes Esau as coming from the desert “exhausted and tired,” then asking his twin for food while saying that he is “hungry and distressed” (jāʼiʻ makrūb).

In an Arabic translation of the Samaritan Pentateuch, the word used is laghib, meaning weary or in great pain (NEST AC 00002, fol. 23v; and NEST AC 00003, fol. 24r). A text from an Armenian Catholic collection reads, “I howl out of hunger,” or ʻawaytu mina al-jūʻ (BzAr 00222, page 54).

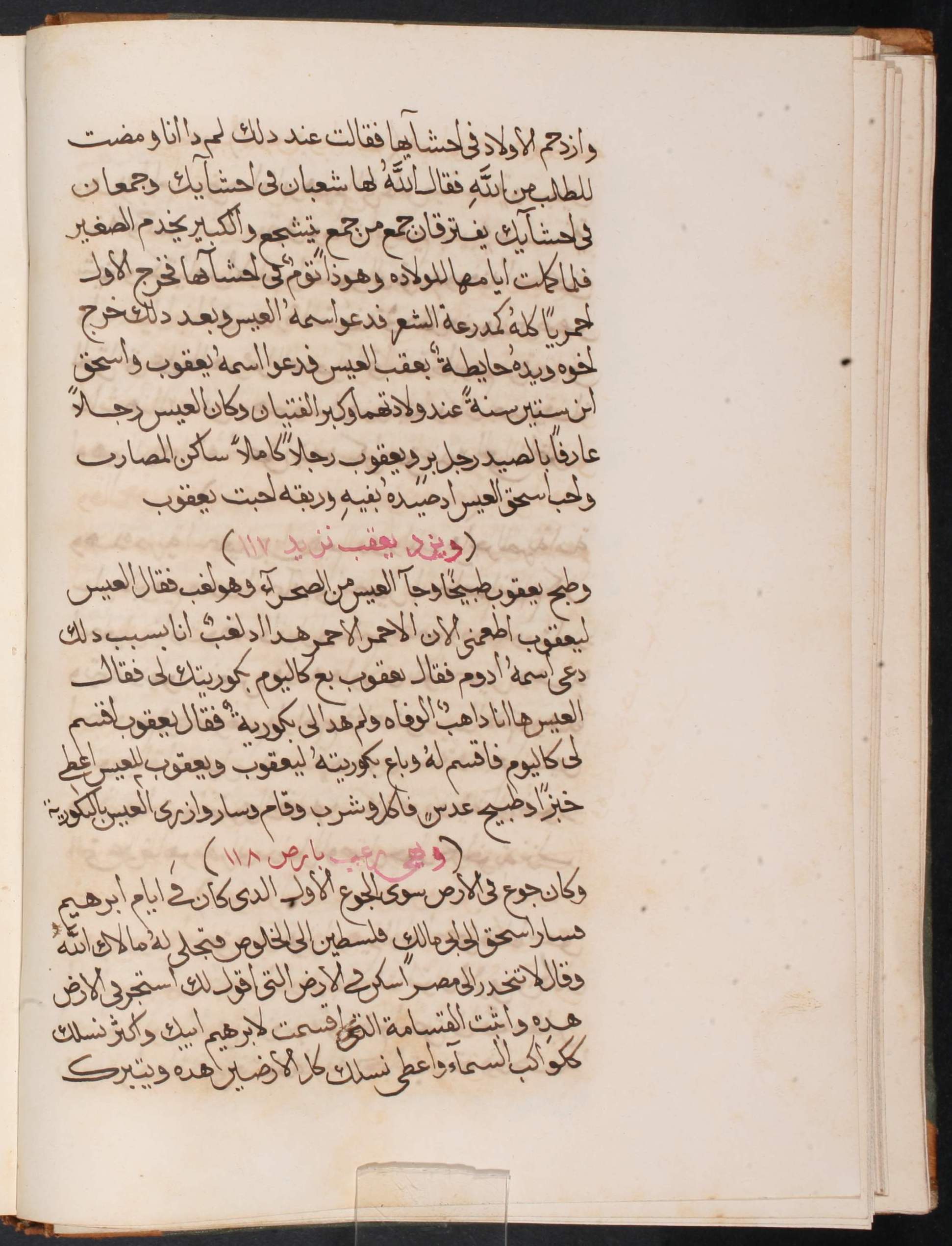

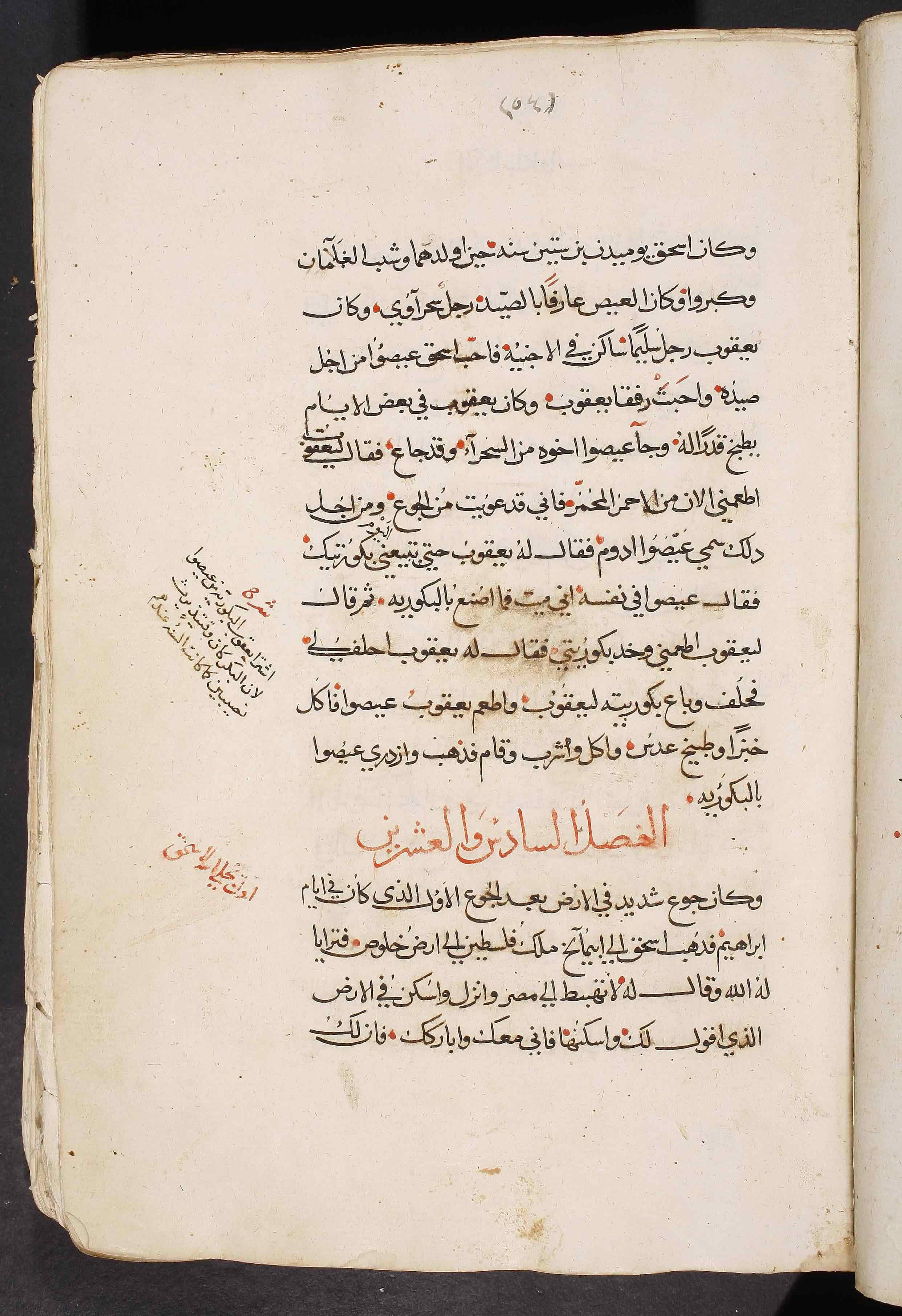

It seems, then, that this special attention to Esau’s state was common among Arabic-speaking Christians from different traditions. This becomes clearer when we turn to Arabic commentaries on the passage. For instance, in the commentary of Marquṣ ibn al-Qunbur (ABMQ 00001, page 122; and SMMJ 00267, fol. 118v-119r), Esau describes himself as khāwī, or empty. This could be understood in two different ways: either that he returned from hunting empty-handed, and thus had nothing to cook, or that he returned with an empty stomach (i.e. feeling hungry).

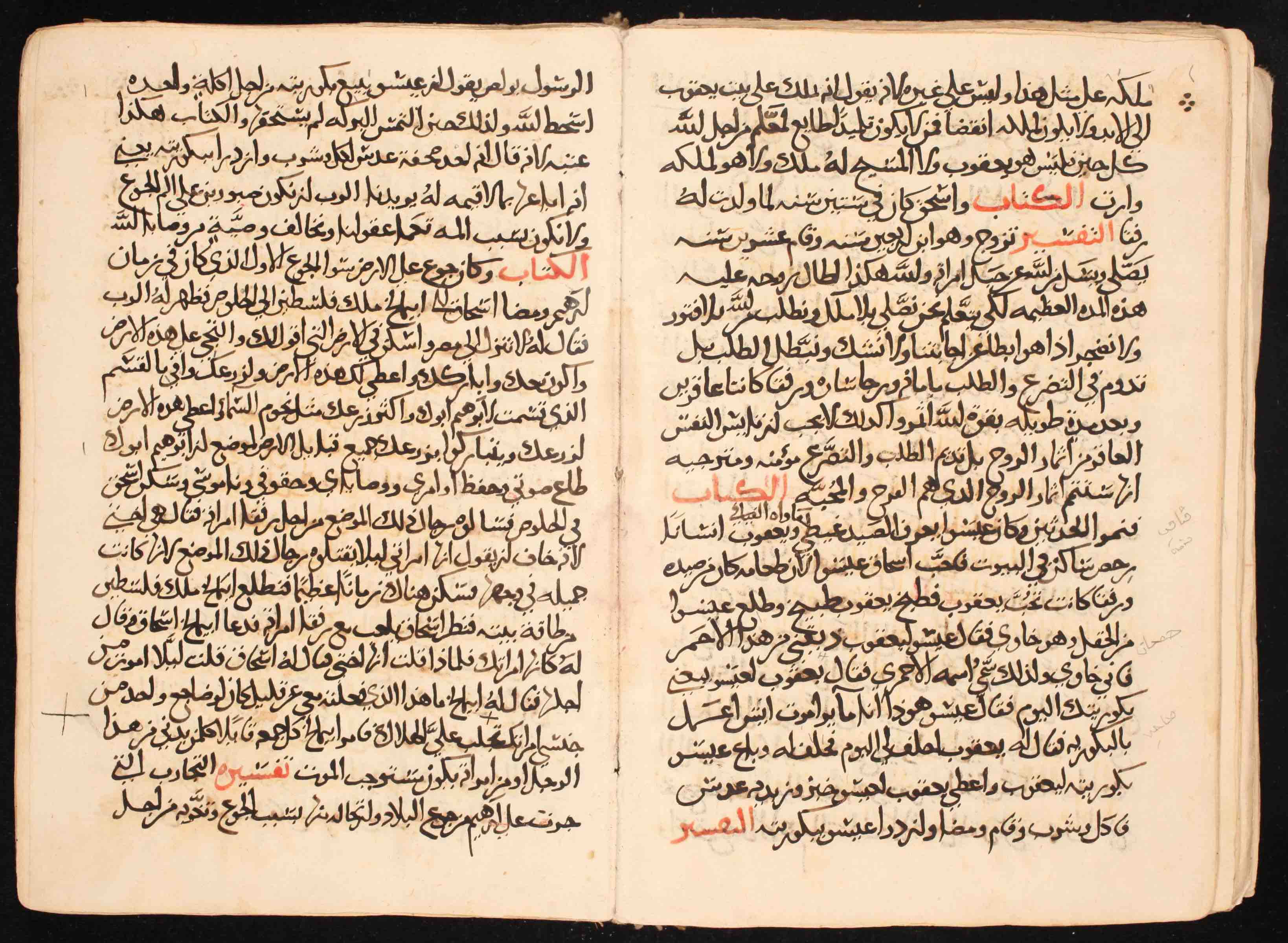

Another interpretation is found in the translated homilies of John Chrysostom, which are widely recognized across Arabic traditions. In one of his homilies on Genesis (BALA 00102, fol. 358), Esau is described using the phrase ishtadda bihi al-gharath wa ḍaʻufat nafsah lidhalika, or “he suffered intense hunger and became weak in front of this [food].” When Jacob made birthright the condition, Esau wondered in himself about the benefit of the birthright when he was on the brink of starvation.

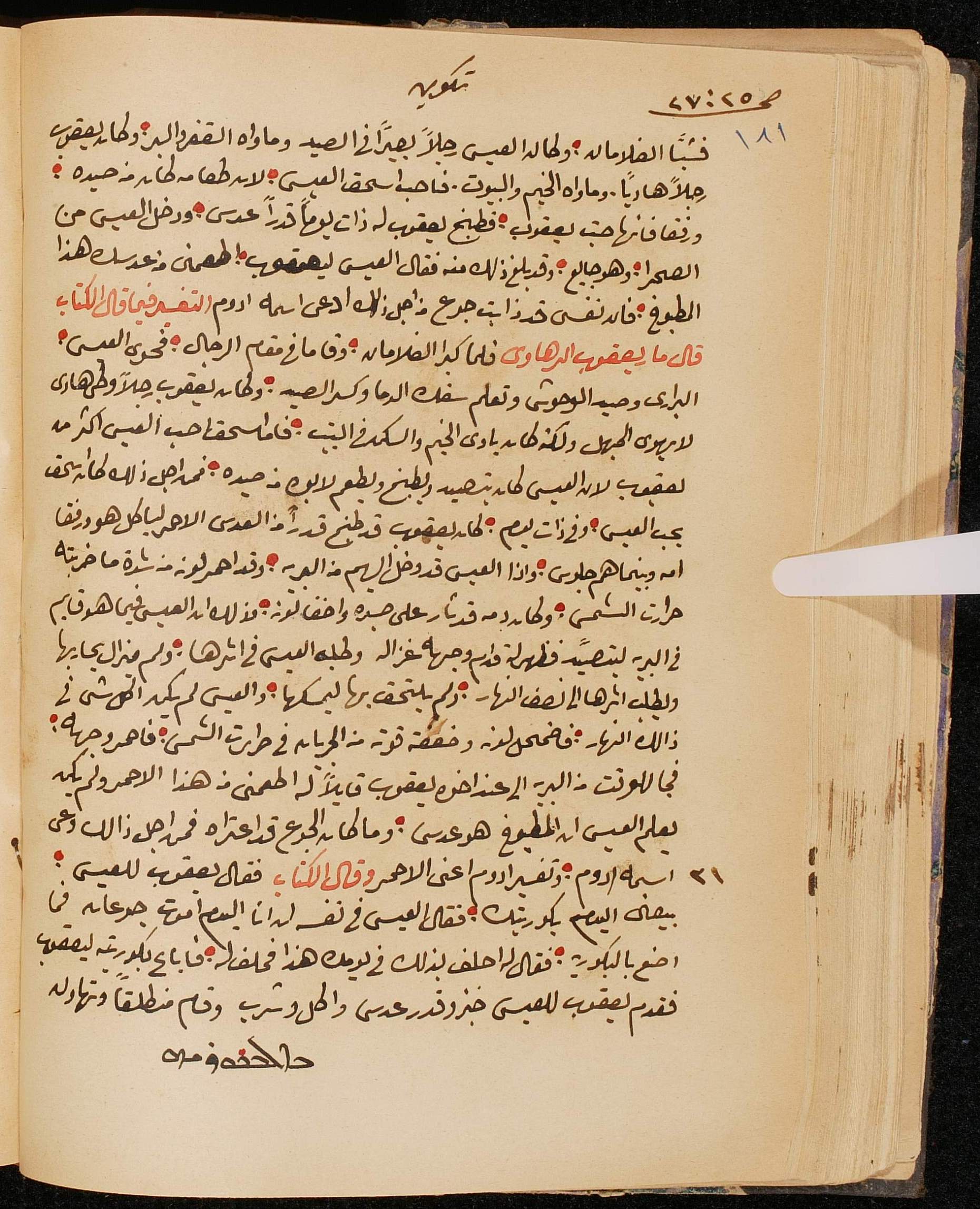

We may also consider the commentary attributed to Jacob of Edessa (see CFMM 00085, page 181; and SCAA 00001 06, fol. 103r), which explains Esau’s hunger through a narrative that demonstrates in detail the difficulties of the hunting trip from which Esau had just arrived.

As the narrative goes, Esau was in the desert hunting when he noticed a deer running before him. He chased the deer under the heat of the sun until noon but did not manage to catch it. He arrived home almost fainting from exhaustion and hunger, red from sun exposure, to find his brother Jacob and his mother Rebecca eating. Esau asked his brother for some food, saying, “My soul has melted out of hunger.” From here the story continues as in the Bible.

Taking into account the different Arabic versions elaborating on the starvation of Esau, and the commentary which explicitly provides a reason for this hunger, the question becomes: could this be an attempt to excuse him for abandoning his precious birthright? In fact, commentators usually end their interpretation by blaming Esau for such an irresponsible act. However, Arabic manuscripts provide compelling insight into attempts to do justice for Esau through considering his motives and the conditions he had experienced.

The moral of the story remains: do not abuse those who suffer hunger, and be careful and patient when you are hungry so as not to be manipulated and sacrifice your privileges.