The Gouda Life

The Gouda Life

This story is part of an ongoing series of editorials in which HMML curators and catalogers examine how specific themes appear across HMML’s digital collections. From the Art & Photographs collection, Katherine Goertz shares a story about Food.

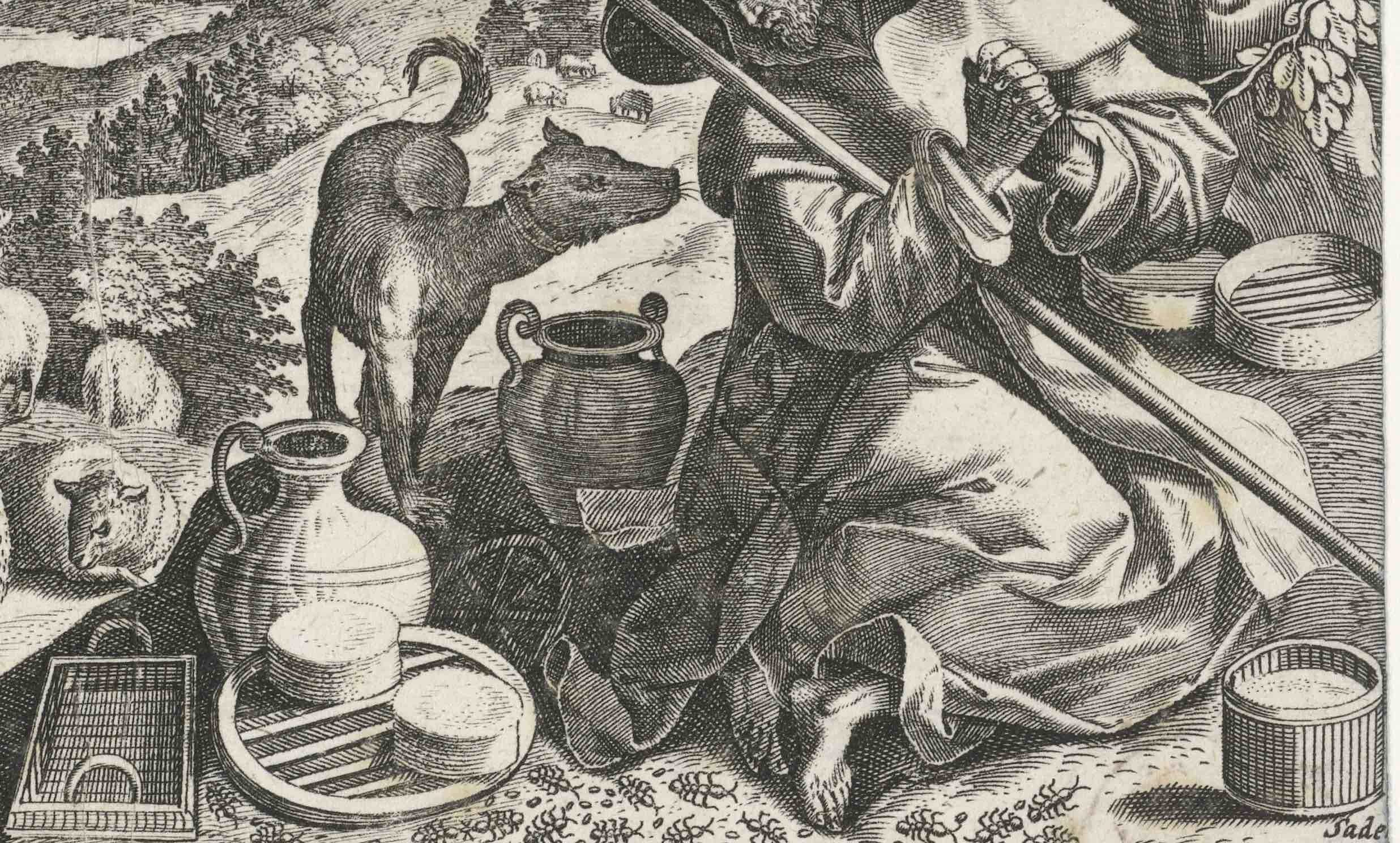

Between 1585 to 1600 Maarten de Vos designed 141 engravings depicting hermits. In St. Malchus of Syria, from the 1585–1587 series Solitudo sive vitae patrum eremicolarum, the saint is shown as a shepherd in a distinctly Low Countries setting (the coastal lowland region of Belgium, the Netherlands, and Luxembourg)—with the addition of fantastical, Italian Renaissance-style mountains. The saint is surrounded by his happy sheep and attended by a curious dog. At his feet we find the subject of our story today: St. Malchus has brought into the field some of the equipment needed to make sheep’s milk cheese.

In the four and half centuries since this print was made, cheesemaking equipment has changed very little. St. Malchus is depicted with bentwood sieves to separate the curds from the whey. His shepherd’s crook could double as a scoop for the cooked curds. There are containers to hold the milk and the whey, and a little wicker tray to hold the cheese. In the right corner, a wheel of cheese sits in a mold, which will transfer a distinctive imprint onto its rind. Finished wheels of cheese are drying on racks at the saint’s feet. The cheese itself probably isn’t much different than cheese that can be bought today. It’s likely Gouda, which dates at least to the medieval period and was a cheese so popular in the Low Countries it became part of the region’s identity.

Why has de Vos chosen to include cheese in his depiction? One possibility has to do with religious symbolism in art. Cheese, as not only a perishable food but a food made by intentionally souring milk, can have associations of decay. This symbolism of decay can be literal, making the cheese a sort of dairy-based memento mori. It can also be spiritual. The little insects that congregate around the saint’s equipment may suggest this meaning. As cheese emerges as a wonderful new food from “ruined” milk, it could suggest the possibility that the human spirit can emerge re-formed from sinfulness or death.

Another possibility is that the cheese suggests the richness of the Low Countries. Antwerp had long been one of the world’s most important commercial cities, and dairy products were part of the area’s bounty. Cheese is a central subject in an engraving designed by Frans Floris, made a little over ten years earlier. Floris’ engraving depicts Pales, the Roman goddess of shepherds, surrounded by cows, sheep, cheese, and milk. Is de Vos’ depiction of St. Malchus’ cheese related to this allegory of plenty?

There’s a third possibility. The wealth of detail in de Vos’ hermit series suggests an artist having fun with his imagery, taking advantage of the breadth of his subject to portray things that caught his fancy, often items of everyday life in Antwerp. In several of the hermit engravings, spectacles and spectacle cases appear, an item completely foreign to the desert hermits but increasingly common, though expensive, in de Vos’ Antwerp. There are depictions of kitchenware and cookware, many examples of the kind of buildings that de Vos would have seen every day, and even details that give us a good idea of what Antwerp’s residents would have worn every day.

There were other Low Countries artists who dwelled on the fascinations of everyday life. De Vos’ contemporary Joachim Beuckelaer was known for his cascading and overflowing masses of food. The Four Elements: Air: A Poultry Market with the Prodigal Son in the Background depicts two rounds of cheese, also probably Gouda. More cheese appears to be loaded onto a sled in the far background.

Beuckelaer's painting is technically religious, though the positioning of the supposed centerpiece of the painting (the Prodigal Son) far from the riotous detail of the foreground suggests that religion is more pretext than subject. Like Beuckelaer, de Vos regularly includes food in the hermit series, though his presentation is usually more restrained.

So, what is it? Why the cheese? Is it a commentary on the transitory nature of life? A recognition of the supremacy of Low Countries dairy products? Or just an opportunity for adding everyday, 16th-century interest to an engraving depicting a fourth-century saint? In the complicated symbolism of 16th-century Flemish art, de Vos could have had all three in mind.