Soup, With A Side Of Reform

Soup, with a Side of Reform

This story is part of an ongoing series of editorials in which HMML curators and catalogers examine how specific themes appear across HMML’s digital collections. From the Art & Photographs collection, Dr. Catherine Walsh shares a story about Food.

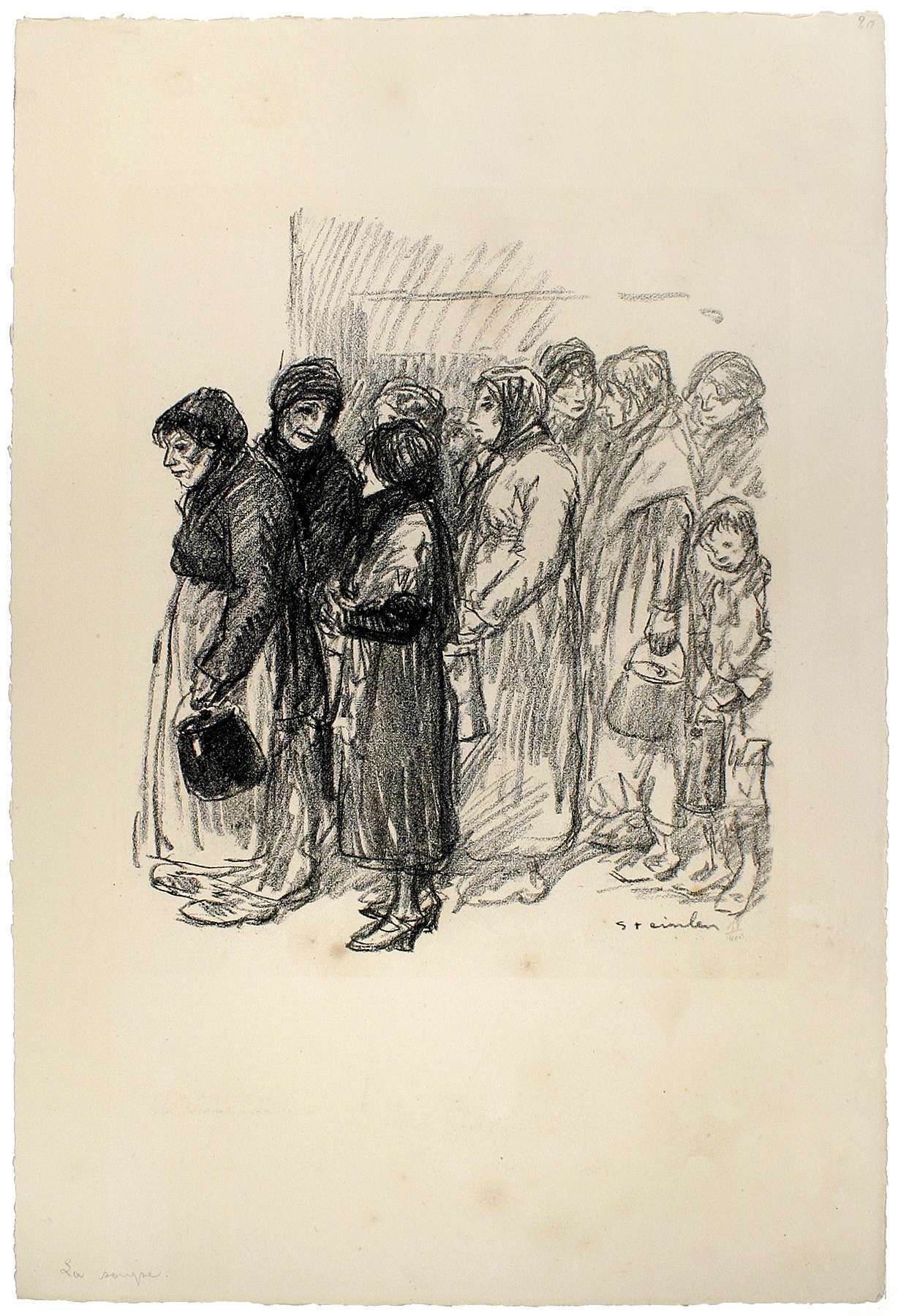

In a black-and-white lithograph that Théophile Alexandre Steinlen created in the 1890s—La Soupe—it is not the presence of food but rather its absence that immediately strikes the viewer.

A group of women cluster together, several clutching the handles of lidded pots. Rather than gathering for a convivial communal meal, they stand in a densely packed line waiting for a distribution of the titular soup. Some women converse, yet this is clearly a representation of hardship. At the left, a woman stands with slumped shoulders and in determined isolation—despite the others pressed uncomfortably close behind her. A small boy echoes her posture at the right, also holding a pot.

While this image may have been drawn from life, the choice to represent women and children was likely a conscious strategy, designed to play upon the emotions of viewers by casting the hungering poor in the trope of unthreatening, sympathetic women and children. The artist wanted this image to do work, to help serve the cause for which he passionately created hundreds of similar lithographs: social reform in France.

In 1881, Swiss-born artist Steinlen moved to Paris, where he settled in the notoriously bohemian neighborhood of Montmartre. Today, he is perhaps best known for his brilliantly colored lithographic posters highlighting the cafes, commercial culture, and entertainment available to middle-class Parisians in the 1880s and 1890s.

However, from the moment of his arrival in the city, Steinlen was artistically driven to represent the street life of Paris and the plight of the urban poor. As he wrote: “On my first day here I was seduced by the world of the street, by the workers and errand girls, laundresses and poor people” (quoted in Miller, 72).

Abetted by the 1881 lifting of censorship in France and passage of laws protecting the freedom of the press, over the next decades Steinlen created a massive amount of political ephemera to support socialist causes and working-class rights. Much of this stood in stark contrast to his more commercial output. His political lithographs appeared regularly in leftist and anarchist periodicals, such as Gil Blas (art criticism), the satirical Le Rire, and the magazines Le Chambard Socialiste and La Feuille.

Throughout Steinlen’s career, he returned several times to the subject of food—its presence and absence—in his reformist lithographs.

Soupes Populaires

The 19th century saw growing urbanization and industrialization in Paris, which brought with it increasingly harsh conditions for the working classes. The city made efforts to ameliorate these conditions, providing some services, particularly helping the children of districts like Montmartre. These services included dispensaries for medical care, schools, and day nurseries for working mothers.

One of the most common such services were soupes populaires—institutions that provided subsistence meals for residents of the arrondissement (administrative districts) of Paris. For example, in 1898, funds totaling 17,700 francs were distributed by the Paris Conseil to soupes populaires, for 25 separate establishments spread across 16 arrondissement throughout the city (“Délibérations du 24 Décembre 1897,” 1094).

This money helped, but the soupes populaires needed additional sources of funds in order to continue their work. Steinlen’s art served the cause.

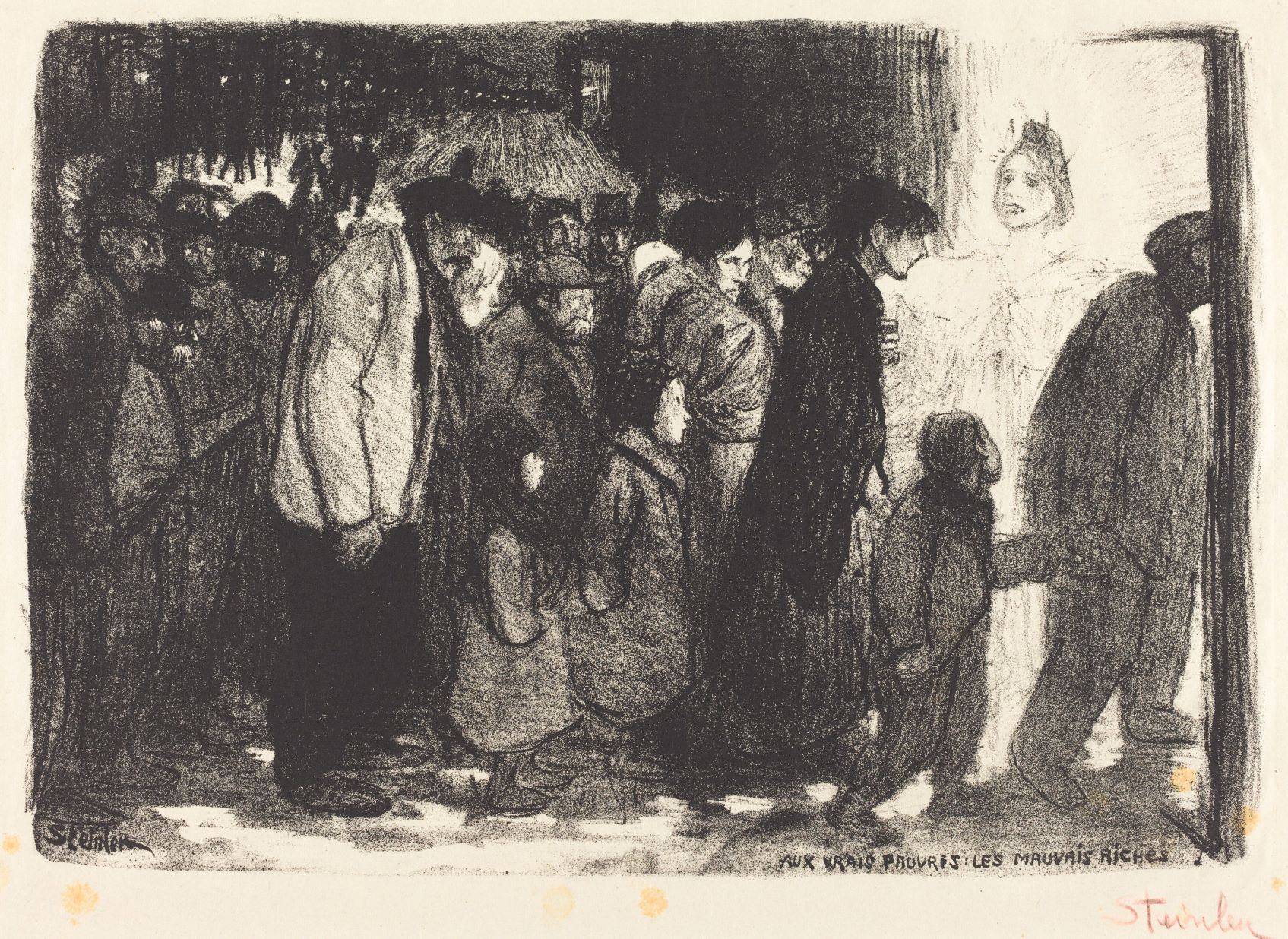

In early 1895, Steinlen produced the lithograph Aux Vrais Pauvres: Les Mauvais Riches, a crayon drawing made for the program of a celebration held on February 10, 1895, to profit the Soupe Populaire de Saint-Fargeau in the 20e arrondissement. In this image, a line of men, women, and children walk from the dark streets of the city through a gleaming portal, past the shining personification of France, Marianne, in her characteristic phrygian cap representing liberty.

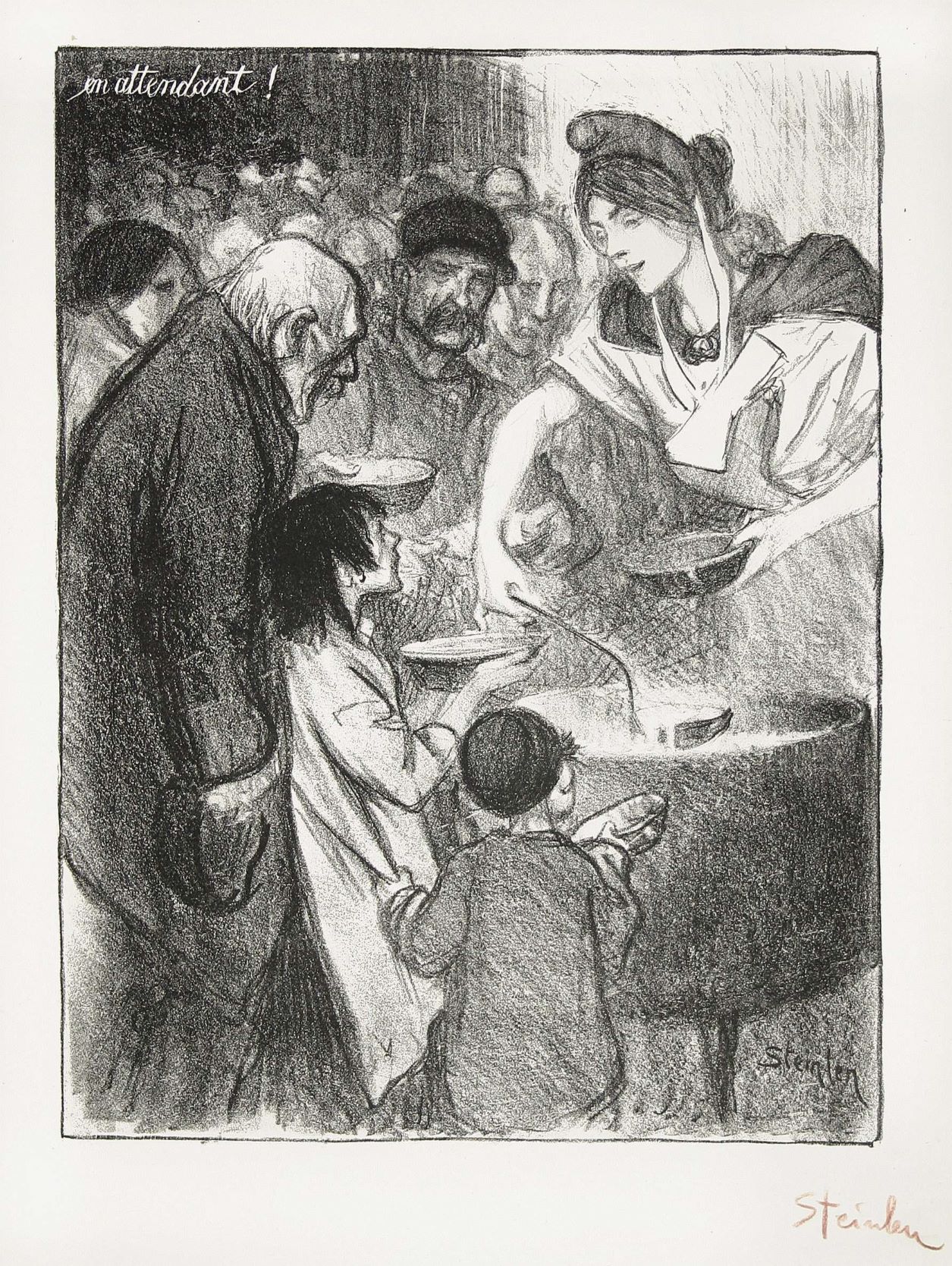

Just one month later, Steinlen turned his attention to the subject again, in En attendant. For one soupe populaire, Batignolle-Epinettes in the 17e arrondissement, fundraising had failed. En attendant accompanied the program of the Concert-Conférence for the closing of the soupe populaire, held at the Concert des Fleurs on Saturday, March 30, 1895. Once again, Marianne prominently intervenes in the plight of the city’s poor. Here she actively ladles soup—the first time food has been physically represented in this set of images!—into the waiting dishes held by two children who gaze up into her kind face. This establishment was closing, but clearly Steinlen was arguing that the need for France to continue serving her citizens had not vanished.

A Powerful Contrast

Sometimes it can be difficult to reconcile the two drastically different types of art found in Steinlen’s oeuvre. He passionately advocated for the plight of the working poor. He also produced many commercial advertisements, and his remarkable affection for cats shines forth in many of his most popular works. A 1924 obituary for Steinlen focuses on the latter, taking the time to name his two Siamese cats (Masseida and Steinlen, if you’re curious!).

It may be helpful to view these bodies of work as cooperative, rather than opposing, forces.

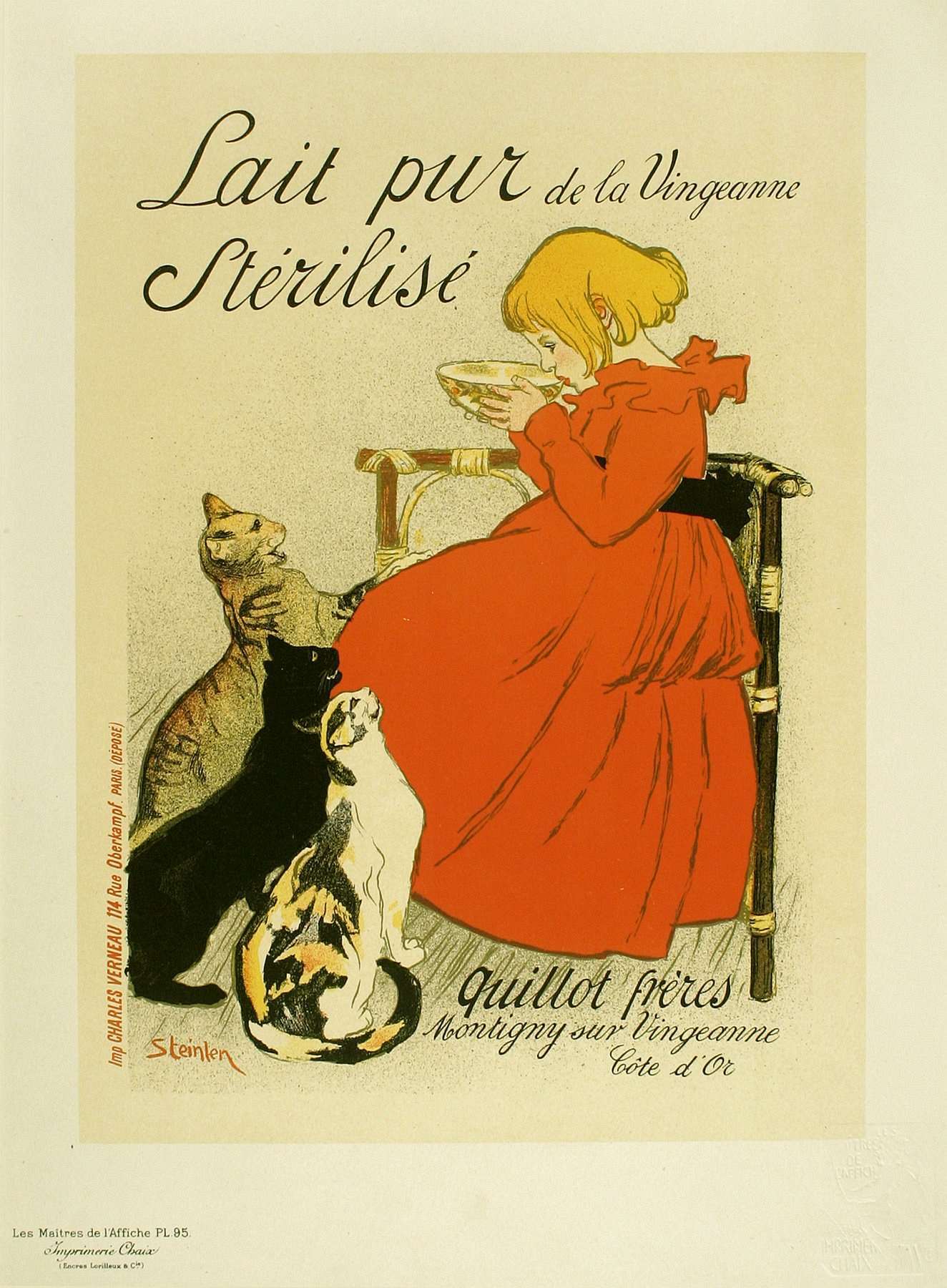

Consider Steinlen’s lithograph Lait pur stérilisé de la Vingeanne, originally produced for the Quillot Brothers dairy in 1894, with the artist’s own daughter, Colette, as the model. This advertisement showcases a healthy, happy child in a tidy bourgeois setting, drinking milk from a bowl while three cats beg for their share. This milk is pasteurized, a product of modern sanitation to produce carefully hygienic food, and in such excess that one might expect to share it with beloved pets. This healthy middle-class child might lurk in the minds of Steinlen’s viewers: what childhood should be, and how children should eat.

It is against this standard that we might view the equally stereotypical child in En attendant, a child with ragged hair, an oversized smock to emphasize thinness, an entreating gaze, and an empty plate. For Steinlen, the audiences for both were the same: people with the economic power to consume goods and to exercise that power to help others.

Further Reading:

Magdalyn Aslmakls, “War, Socialism, and Cats: Théophile-Alexandre Steinlen's Political Artistic Practice,” The Met, November 2, 2017.

Jill Miller, “Les enfants des ivrognes: Concern for the Children of Montmartre,” Montmartre and the Making of Mass Culture (Rutgers University Press, 2001), 72-94.

L’oeuvre gravé et lithographié de Steinlen: catalogue descriptif et analytique suivi d’un Essay de bibliographie et d’iconographie de son oeuvre illustré (Paris: Société de Propagation des Livres d’Art, 1913).

Conseil Municipal de Paris, “Délibérations du 24 Décembre 1897,” in Délibérations (1898), 1094.