Smoking In The Desert — Between Supporters And Opponents Of Tobacco

Smoking in the Desert — Between Supporters and Opponents of Tobacco

This story is part of an ongoing series of editorials in which HMML curators and catalogers examine how specific themes appear across HMML’s digital collections. From the Islamic collection, Dr. Ali Diakite and Dr. Paul Naylor share a story about Food.

The use of tobacco in the Sahel, whether smoking, chewing, or taking as snuff, was widespread and longstanding. The product arrived in the region as early as the 1600s—Ahmad Baba, the famous jurist from Timbuktu, wrote a fatwa (a ruling on a point of law) allowing its use in 1607.

According to Mauro Nobili (Sultan, Caliph, and the Renewer of the Faith, 2020), by the nineteenth century, tobacco had become a major item of trans-Saharan trade and was especially associated with the city of Timbuktu. The French explorer René Caillié, who visited in 1828, noted that tobacco was even cultivated in the fields surrounding the city, although at quantities and qualities inferior to that imported from the Americas.

However, the use of tobacco was also controversial. In 1821, Ahmad Lobbo, founder of the Laamu Diina, a religious state in the Mopti region of present-day Mali, banned tobacco across all his domains. His ban was probably just as much based on health and morals as it was on politics.

The trade of tobacco through the Laamu Diina was controlled largely by the Kunta, a prosperous family of merchants and religious savants. Laamu Diina notables and the Kunta exchanged several diatribes for and against the trade. The Kunta maintained that tobacco was simply an herb and, like other herbs, there was no controversy as to its use. Meanwhile, Lobbo quoted Qur’anic verses against the ingestion of harmful substances and complained that those who chewed tobacco frequently needed to spit, making mosques and houses unclean.

Muhammad al-Kuntī wrote a whole book on the subject; the book does not survive, but we do have a little information about non-elite opinions of tobacco during this period. Two short texts from Timbuktu libraries, found at the beginning and end, respectively, of unrelated longer works, shed light on this issue. The first text, which we have called the “Prophet's advice to ʻAlī ibn Abī Ṭālib regarding smoking,” is an apocryphal text in which Muhammad warns Ali (his nephew and a future Caliph) against the use of tobacco. It begins quite emphatically:

All plants are pure except one plant that grows in the urine of Satan.

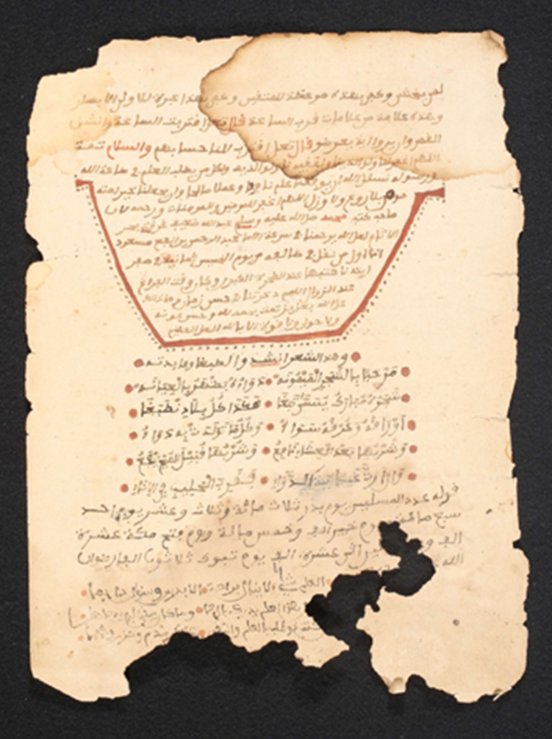

(SAV BMH 22830, page 1)

That plant is, of course, tobacco, which the text states is “more illicit than alcohol,” also stating that whoever smokes or chews this plant has “no religion.” This is followed by assertions that the plant is forbidden in the Torah, the Bible, the Psalms, and the Qur’an, and is followed by a series of fake hadith and Qur’anic passages confirming the same.

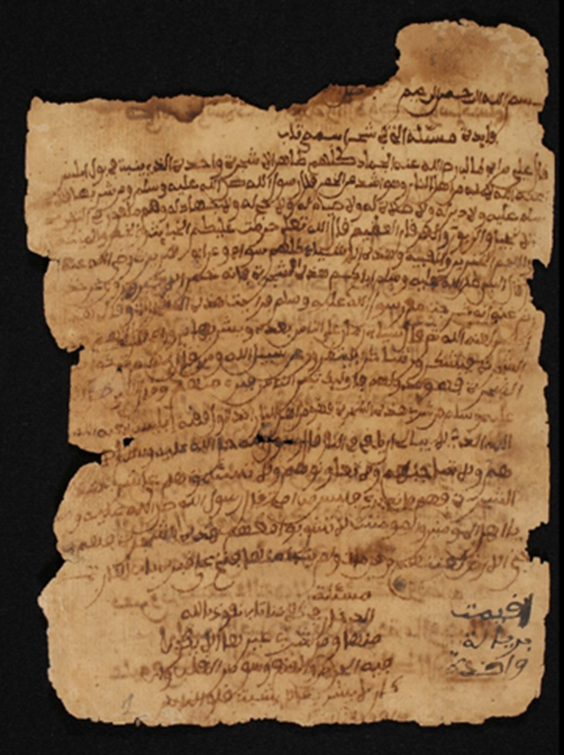

The second text, a poem praising tobacco, deserves to be translated here in full:

Greetings to the well-favored tree Its curative properties so clearly evident Its blessed name is tabaghā Known everywhere as tobacco Both its leaves and its stem Its every part is a remedy Taking it after dinner is beneficial And taking in the small hours healthful If you are looking for the best way Put some milk with it دواءه بظهر بالعناية مرحبا بالشجرة الميمونة هكذا كل بلادِنْطَبْغَا شجره مبارك يسمى تبغا وكل ما تولدت به دواء أوراقه وعرقه سواء وشربها قبيل الصبح ينفع وشربها بعد العشاء نافع فقرب الحليب بالإناء وإن أردت غاية الدواء (ELIT ESS 03799, page 14)

These two works capture the colorful views for and against the use of tobacco at a more popular level, as well as some information as to how tobacco was actually consumed—apparently with milk! And while the poem, in our opinion, has more literary merit, we certainly do not encourage anyone to follow its advice and take up the habit.