A Man For All Seasonings

A Man for All Seasonings

This story is part of an ongoing series of editorials in which HMML curators and catalogers examine how specific themes appear across HMML’s digital collections. From the Western European collection, Dr. Josh Mugler shares a story about Food.

It was the late 14th century, and Shīrāz was the city of poets. Ḥāfiẓ, then an old man, wrote lyric poetry that would continue to captivate his readers for centuries to come and is still found on most bookshelves in modern Iran. A century earlier, Saʻdī had reshaped Persian literature in both poetry and prose; his Gulistān is still considered by many to be the greatest prose work in the language’s history. Even satirical and vulgar poetry, mocking the seriousness of these literary giants and their society, had been perfected by ʻUbayd Zākānī, whose Mūsh va gurbah spins the tale of a tyrannical cat whose regime is overthrown by an army of mice.

It is understandable, then, that a young local poet named Busḥāq, working his day job as a cotton carder, thought that the possibilities of literature had largely been exhausted by authors of prodigious talent, all but impossible to equal. He quotes a Persian verse:

“Whatever verse I may utter, others have uttered it all, and have penetrated all its domain and territory.”

(This and following translations from Edward G. Browne, A History of Persian Literature under Tartar Dominion, pages 344-351).

Busḥāq refers to some of his illustrious predecessors, such as Saʻdī (whose works “by general accord, are like luscious honey to the palate of the congenial”) and Ḥāfiẓ (whose poetry is “a wine fraught with no headache and a beverage delicious to the taste”). Was there any piece of the literary pie left for Busḥāq? These appetizing descriptions hint at the solution that the young poet would discover.

As with so many authors across the centuries, Busḥāq was inspired by his beloved. He described her as a woman “whose eyes are like almonds, whose lips are like sugar, whose chin is like an orange, whose breasts are like pomegranates, whose mouth is like a pistachio-nut.” One year on ʻĪd al-Fiṭr (the holiday for the breaking of the Ramaḍān fast), his beloved expressed that she was not very hungry, in spite of the preceding month of daytime fasting. Busḥāq, inspired by earlier authors who had written aphrodisiac literature for patrons dealing with impotence and the loss of sexual appetite, decided to write literature that would stimulate his partner’s culinary appetite. So was born the author’s text Kanz al-ishtihāʼ, or Treasure of appetite.

By devoting his work to the literature of food, Busḥāq discovered a range of topics that were seldom mentioned in earlier Persian poetry, and he explored them to the full. Although he was inspired by the humorous writings of ʻUbayd Zākānī, his work has little of Zākānī’s satirical edge and instead remains within the lighthearted realm of parody. The surviving poetry collection (dīvān) of Busḥāq consists almost entirely of parodies of the work of great Persian poets, rewritten with a focus on food. For example, a mystical poem of Niʻmat Allāh Valī, Busḥāq’s contemporary, reads:

“We are the pearl of the shoreless Ocean; sometimes we are the Wave and sometimes the Sea;

We came into the world for this purpose, that we might show God to His creatures.”

In Busḥāq’s parodic revision, the couplet now says:

“We are the dough-strings of the bowl of Wisdom; sometimes we are the dough and sometimes the pie-crust;

We came into the kitchen for this purpose, that we might show the fried meat to the pastry.”

Little is known about the life of Busḥāq. As a poet, he is known by several names, including Busḥāq (short for Abū Isḥāq), Ḥallāj (meaning cotton-carder, in reference to his profession), and Shīrāzī, after his birthplace. He is often called Busḥāq-i Aṭʻimah—“Busḥāq of the meals”—or simply Aṭʻimah, because of the content of his poetry. Busḥāq died in Shīrāz in the 1420s, but likely spent time in Iṣfahān as well. His poetry preserves invaluable information regarding medieval Iranian cuisine and kitchen terminology, much of which has yet to be found anywhere else. His style was imitated by several later and contemporary authors, most notably Maḥmūd Niẓām Qārī, who wrote similar parodies but focused on clothing instead of food.

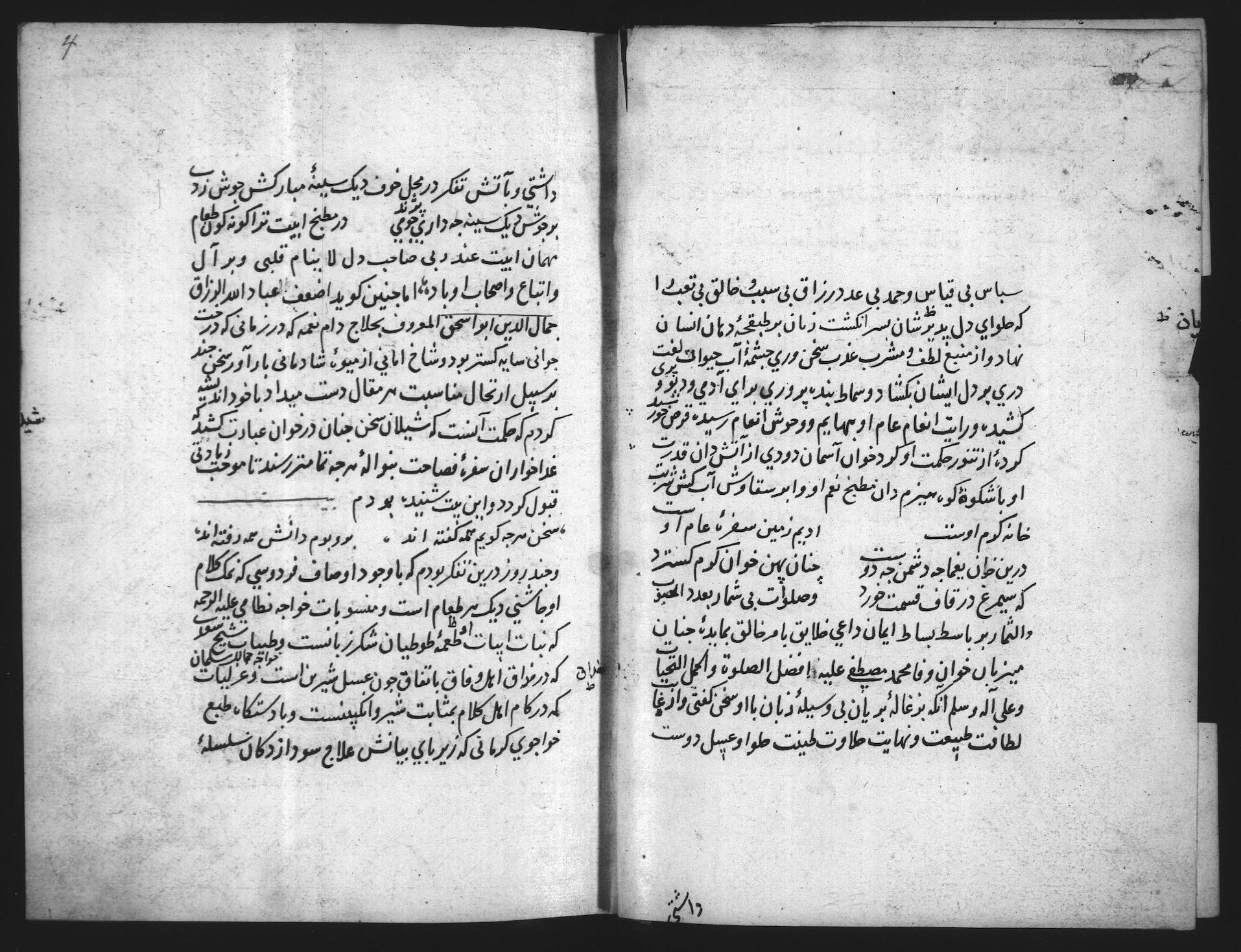

HMML’s microfilms of manuscripts at the Austrian National Library include two copies of Busḥāq’s work: microfilms 22723 (Cod. Mixt. 58) and 22759 (Cod. Mixt. 83). Microfilm 22759 also preserves Cod. Mixt. 84, an imitation of Busḥāq’s work written in Ottoman Turkish by Kerîmî, a 15th-century poet from Bursa.

These manuscripts unite the culinary history of late medieval Iran and the early Ottoman Empire in one great banquet. As Busḥāq puts it, he and his successors have “cooked a meal garnished with verbal artifices and rhetorical devices, and baked in the oven of reflection with the dough of deliberation a loaf which rivalled the orb of the sun in its conquest of the world.”