Treatises Of Consolation: Muslim Scholars Comfort Themselves And Others Who Have Lost Children

Treatises of Consolation: Muslim Scholars Comfort Themselves and Others Who Have Lost Children

This story is part of an ongoing series of editorials in which HMML curators and catalogers examine how specific themes appear across HMML’s digital collections. Examining the theme of “Death & Mourning,” Dr. Josh Mugler shares this story from the Islamic collection.

The Black Death pandemic of the 14th century dramatically reshaped many cultures. Islamic responses to the plague included scholarly treatises such as Ibn Ḥajar al-ʻAsqalānī’s Badhl al-māʻūn fī faḍl al-ṭāʻūn (An Offering of Kindness on the Virtue of the Plague, now published in a 2023 English translation, Merits of the Plague), a text discussed by Dr. Celeste Gianni as part of an editorial on medicine.

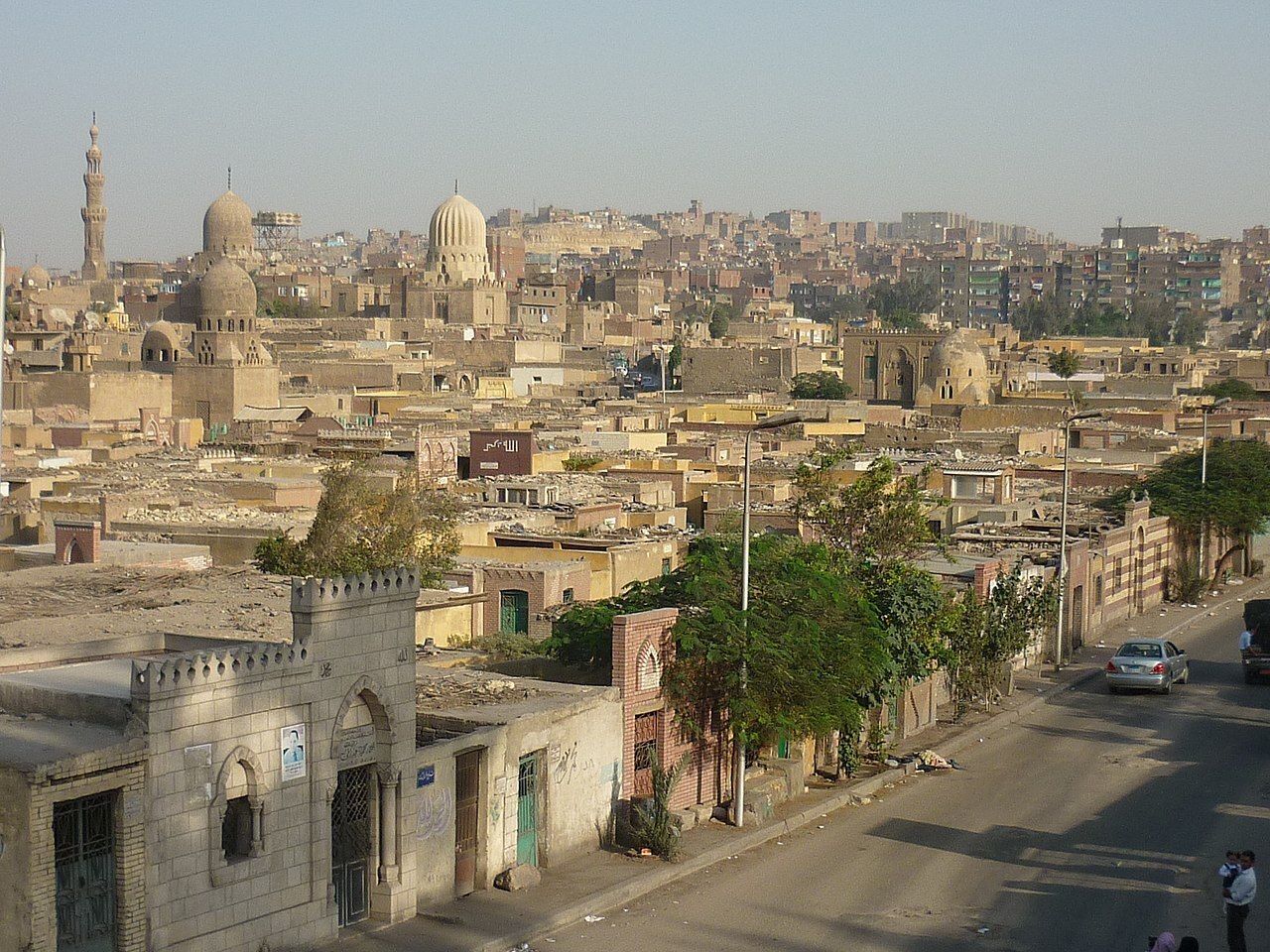

Ibn Ḥajar was an Egyptian polymath scholar and theologian who lived from 1372 to 1449 CE. He lost three daughters to the Black Death. In Badhl al-māʻūn, Ibn Ḥajar mentions that the plagues of the era often killed children in disproportionate numbers, contributing to a death rate that was likely already high. Numerous scholars began to discuss this tragic reality from a theological perspective, writing treatises of consolation for bereaved parents.

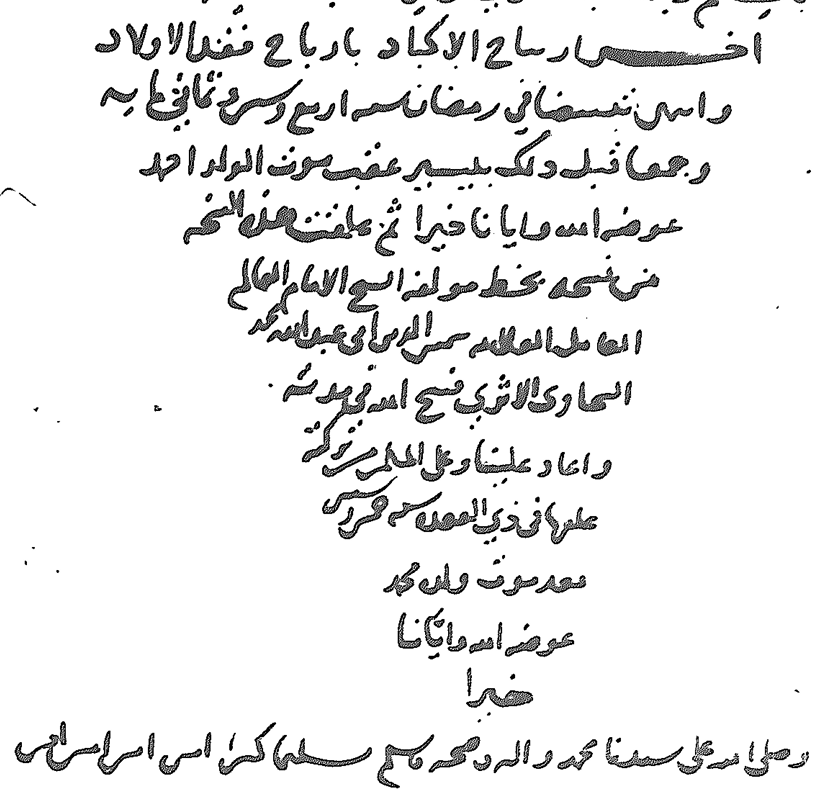

One of Ibn Ḥajar’s most prominent students in Cairo was Muḥammad al-Sakhāwī (1427/1428–1497 CE), who composed the lengthiest and most detailed Islamic consolation treatise identified to date: Irtiyāḥ al-akbād bi-arbāḥ faqd al-awlād (Respite for Livers in the Profits from the Loss of Children, written from a cultural perspective that sees the liver as one of the bodily seats of emotion). A copy held by the Khalidi Library in Jerusalem was digitized by HMML in 2015 (manuscript AKDI 01964 1095).

Like Badhl al-māʻūn, this text commends the religious virtue of steadfastly enduring tragedy with patience, arguing that such a Stoic approach to life shows trust in divine providence and brings reward in the afterlife. But al-Sakhāwī leaves no doubt that the loss of a child is a powerfully traumatic emotional experience for those left behind. He encourages his readers to console bereaved fathers and mothers, and he argues that there is nothing sinful about weeping over a dead child, citing reports of instances in which the Prophet also wept. At the same time, he attempts to channel parental grief into religiously acceptable forms and cautions against some potentially excessive forms of emotional expression.

Al-Sakhāwī’s is, so far, the earliest Islamic treatise of consolation preserved in HMML’s collections. He is followed by a younger Egyptian contemporary, ʻAbd al-Raḥmān al-Suyūṭī (1445–1505 CE), whose prolific scholarly output includes two texts on the topic—one is a short collection of hadith and the other is a more literary exploration. Another short consolation treatise is attributed to the Anatolian author Birgivî Mehmet (d. 1573 CE), and a later text comes from an 18th-century scholar named Muṣṭafá al-Rankūsī.

Many of these texts address personal experiences from the lives of their authors. Birgivî notes that he wrote his treatise as a way to cope with the death of his son, Muḥammad. A note in al-Sakhāwī’s Irtiyāḥ al-akbād mentions that the text was written after the death of al-Sakhāwī’s son, Aḥmad, and that the careful examination of all aspects of this topic was an important project for the great scholar as he worked through his own grief. Al-Sakhāwī was writing for himself almost as much as he was writing for others. In 1461 CE, a year after he completed the text, the manuscript was copied by an unnamed scribe as he dealt with the loss of his own son, Muḥammad. This copy is preserved at the Chester Beatty Library in Dublin.

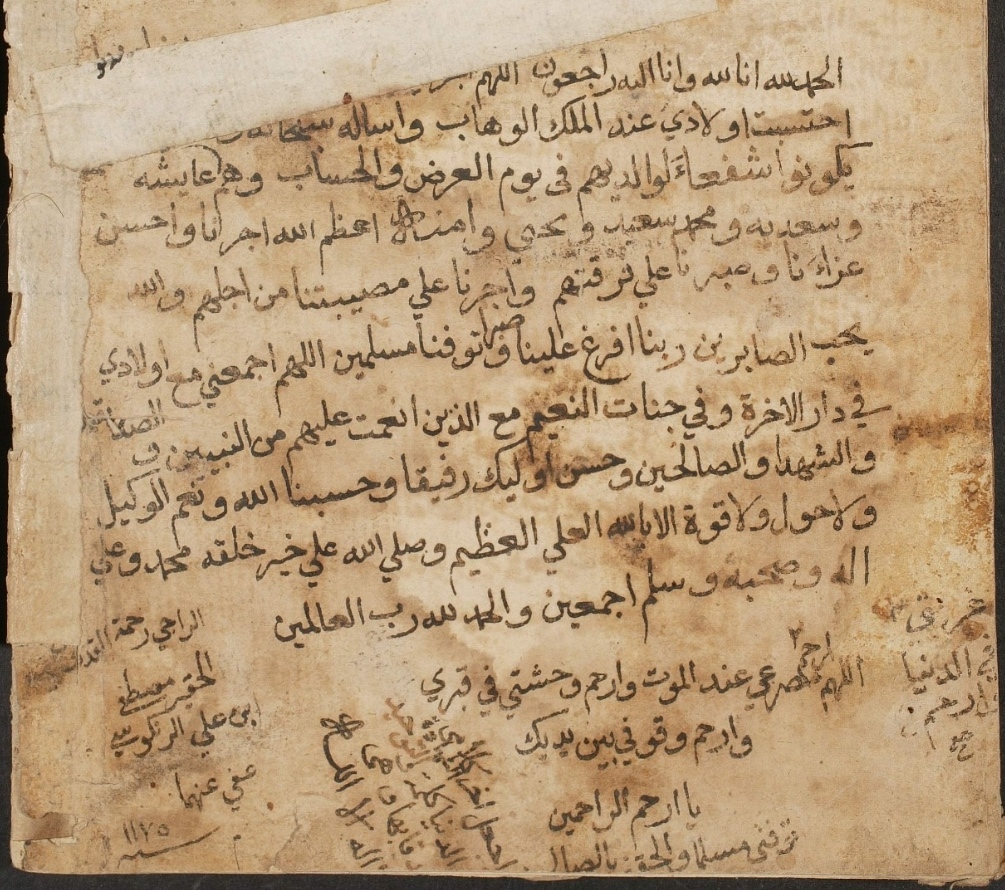

Muṣṭafá al-Rankūsī is completely unknown outside of manuscript GAMS 01240, held at the Fondation Georges et Mathilde Salem in Aleppo, Syria. This autograph manuscript, copied by the author himself, is dated 1761 CE. It includes his own composition on the death of children, and one of the two texts by al-Suyūṭī. On the final page of the manuscript, al-Rankūsī writes a personal prayer asking for patience for himself and eternal reward for his departed children, listing three daughters and two sons by name: ʻĀʼishah, Saʻdīyah, Muḥammad Saʻīd, Yaḥyá, and Āminah. He implores, “O God, unite me with my children in the abode of the afterlife and in gardens of bliss.” We know precious little about al-Rankūsī, but in his manuscript he gave us an intimate window into his personal grief.

Further Reading:

Avner Gilʻadi, “‘The child was small...not so the grief for him’: Sources, Structure, and Content of al-Sakhawi's Consolation Treatise for Bereaved Parents,” Poetics Today 14, no. 2 (summer 1993): 367-386.