Monuments To The Dead

Monuments to the Dead

This story is part of an ongoing series of editorials in which HMML curators and catalogers examine how specific themes appear across HMML’s digital collections. Examining the theme of “Death & Mourning,” Katherine Goertz shares this story from HMML’s Art & Photographs collection.

Grief, loss, and death itself were very much part of 17th- and 18th-century European art. Themes of daily life were popular among the image-hungry audience, and what is more universal to every life than death?

Engravings memorializing recently deceased celebrities were widely available at the print dealer’s shop or stall. Images depicting funeral ceremonies and monuments for the notable dead were also easily found, in works such as an engraving depicting the funeral of Emperor Ferdinand II (AAP0912). Other genres, like memento mori (remember you will die), prompted viewers to consider their own mortality. Such images relied on a visual language of symbols and allegories, readily understood by audiences of the time: obelisks, stopped clocks and run-out hourglasses, willow trees and wilted roses, and veiled mourning women.

Design for a Memorial

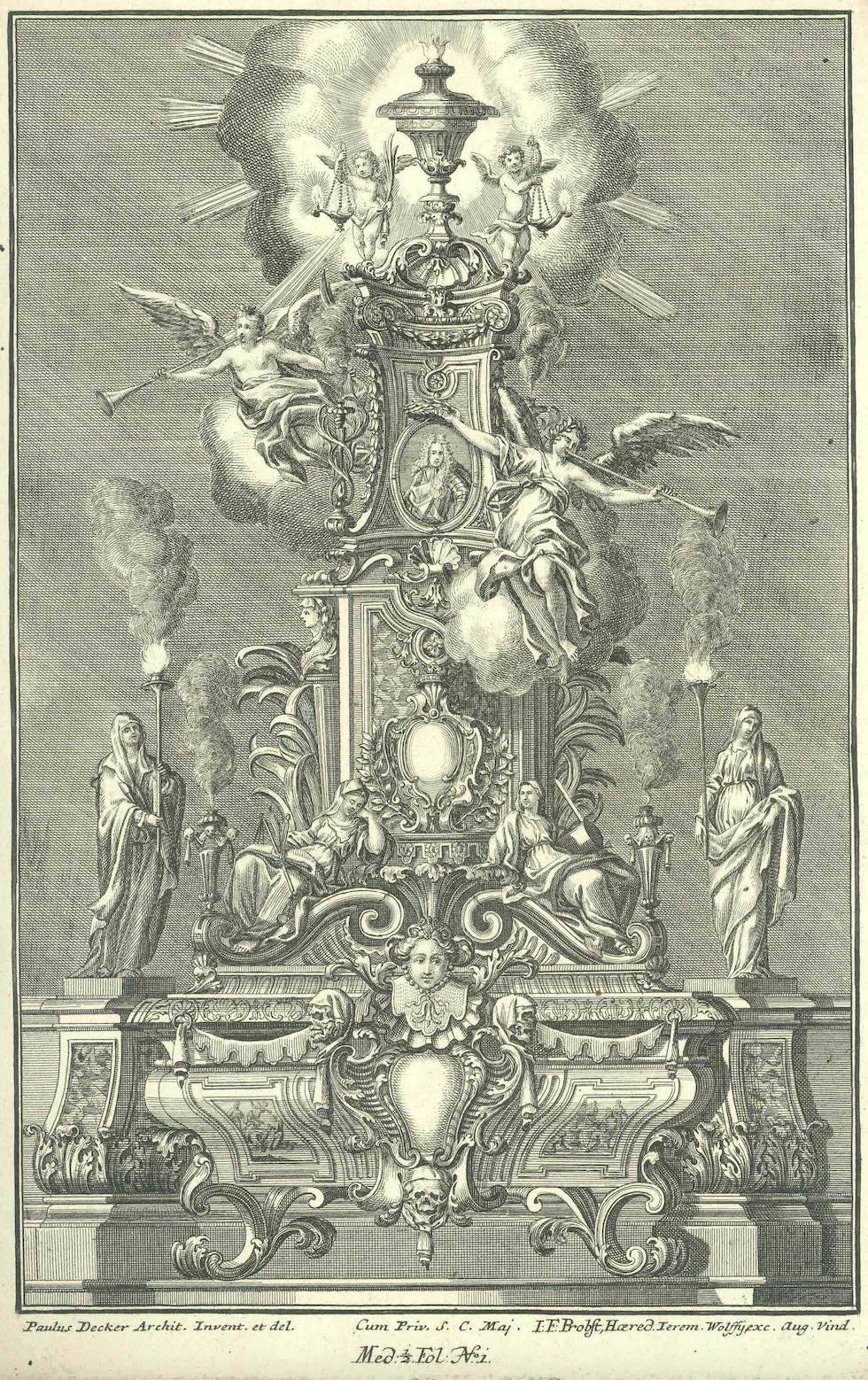

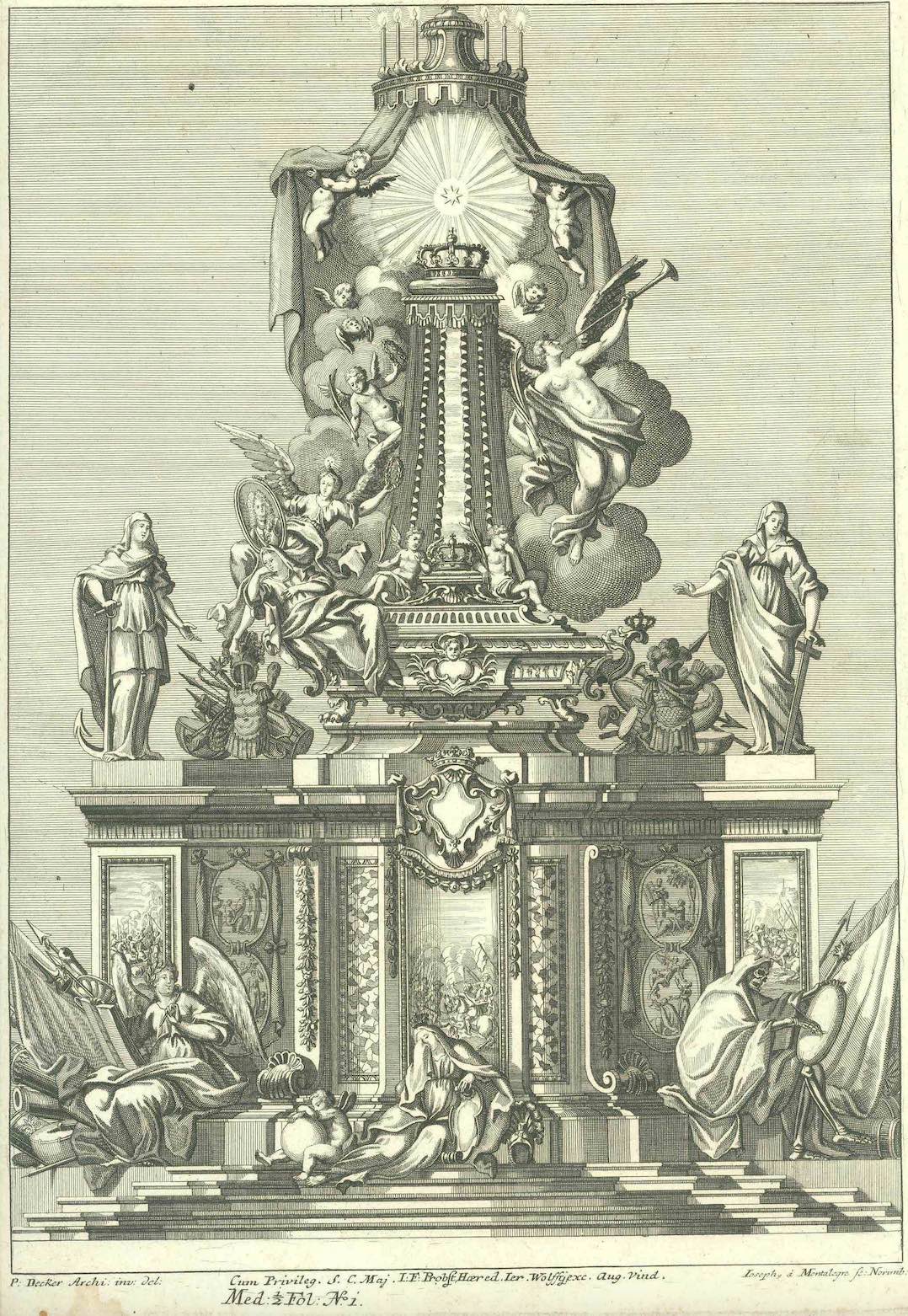

Two engravings designed by the German court architect Paul Decker in the early 18th century (AAP3313 and AAP3314) use an obelisk as the central design element for a memorial monument. Baroque and highly ornamental, the details and flourishes covering the obelisks depict the deceased as men of renown. A representation of Fame, proclaiming the deeds of great people, blasts a long trumpet. Laurel wreaths and torches, symbols of accomplishment, appear throughout.

These celebrations of life are mirrored by symbols of death. Design for a memorial with a casket (AAP3313) depicts extinguished torches among the lit: like the lives of humankind, a torch’s fire is doomed to burn out. In Design for a memorial with Death and the Recorder of Deeds (AAP3314), a veiled mourner sits at the foot of the obelisk, her hand held to her face in grief. Death itself appears in both prints. In the first, Death is a skull, decorating swags on smoking torches and on the casket at the foot of the obelisk. In the second, Death is shown as a full skeletal figure; the frame Death contemplates encircles a blank interior, denoting a life that has ceased.

In neither engraving is the deceased—seen in the small oval portraits attended to by winged figures—the centerpiece of the composition. Decker is known for his fanciful designs for buildings and spaces never meant to be built. Like Decker’s designs for imaginary palaces, these obelisks are theoretical. The portraits under which Decker’s veiled women mourn are not of real men. Instead, Decker’s two engravings dwell on the company and aesthetics of grief. The subject toward whom that grief would normally be directed is unimportant.

Design for the Memorialized

It was much more common, in the artwork of the time, to mourn for an actual person. In 1734, the Dutch engraver Jacobus van der Schley memorialized his teacher, the great French-born Amsterdam printmaker Bernard Picart, in Memorial portrait for Bernard Picart (AAP0474). In the engraving, a distraught putto gestures toward Picart’s face as his compatriot comforts him, a laurel wreath held in his hand. To the right, a winged figure, likely the Recorder of Deeds, also turns away in mourning. Her book is shut on Picart’s life; it would be open if he were still living. Picart’s own engraving work lies at her feet and his engraving tools are scattered nearby, left behind by the artist.

Despite these allegorical references, Picart’s portrait is the clear focus of the memorial. Unlike the Decker engravings, which use mourning as a pretext to exhibit exuberant architecture and ornament, van der Schley’s depiction of his teacher is a personal image of grief.

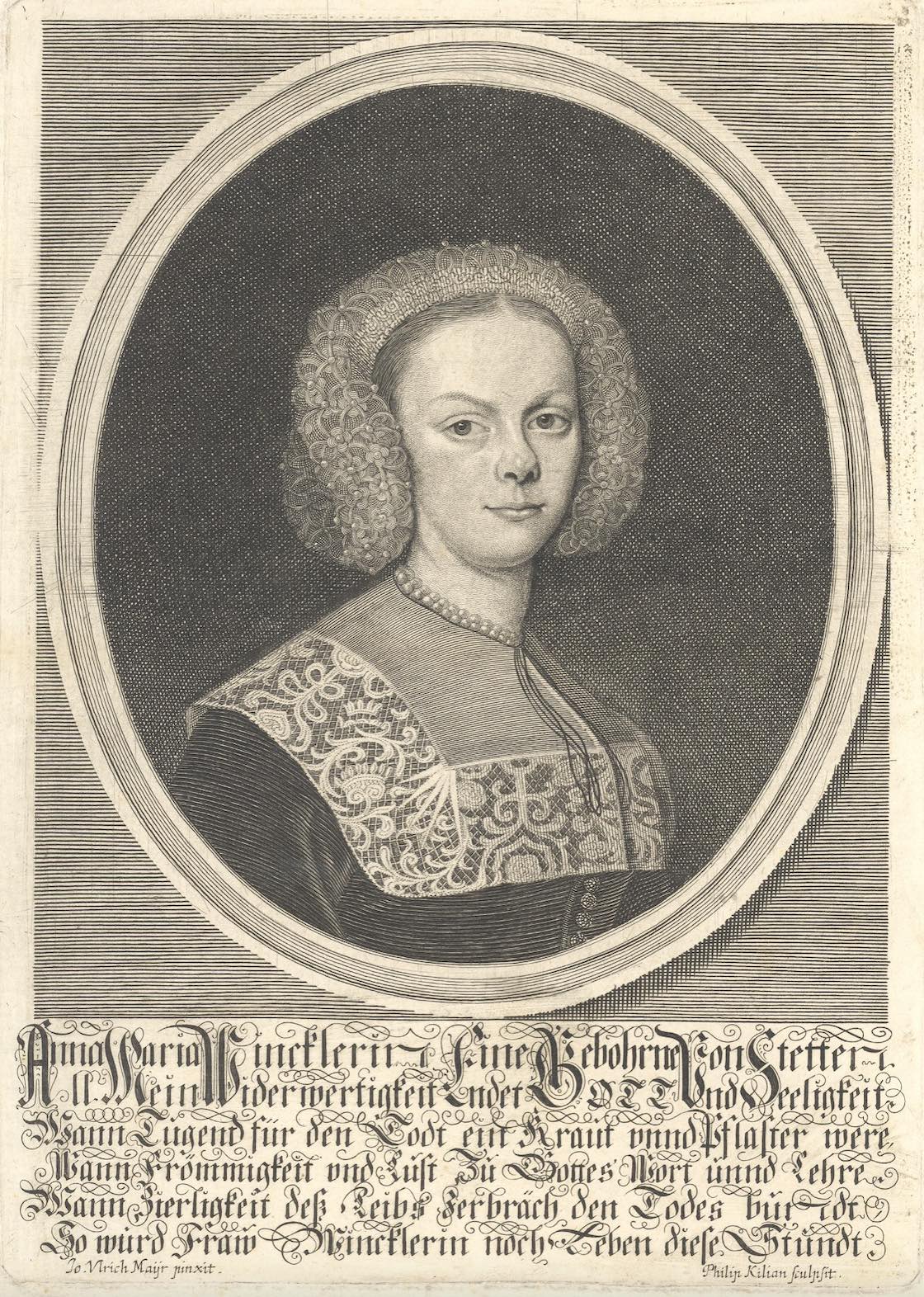

Personal grief, translated into a popular image, is the subject of another engraving in HMML’s Art & Photographs collection, made some sixty years earlier. Around 1668, a portrait of Anna Maria Winckler was painted in Augsburg, Germany, by the German Baroque artist Johann Ulrich Mayr. In the portrait, Anna Maria wears a flat collar of lawn and bobbin lace over a dark dress, appropriately fine clothes for the wife of a Handelsherr (powerful merchant). Covering her hair is a crocheted lace snood, dotted with little pearls. Her eyes look straight out of the frame at the viewer, with a little smile on thin lips. Soon after Mayr painted her, Anna Maria died at the age of 29.

Mayr’s portrait, along with his portrait of Anna Maria’s husband Benedikt, was copied as an engraving and offered on the Augsburg print market. Though Anna Maria’s portrait had become posthumous, engraver Philipp Kilian added no traditional symbols of mourning to the image—no death’s heads, skeletons, or veiled figures, nor extinguished torches or angelic putti. To a literate audience, however, the engraving would still have been instantly understood as a memorial to Anna Maria. A poem appearing below her calm face, probably composed by her husband, makes Anna’s death (and the grief of the writer) clear.

“Anna Maria Winckler, born Von Stetten

God and salvation put an end to all my adversities,

If virtue would be an herb and dressing for death

If piety and joy in God’s word and teaching would also be,

If physical charm could break the bonds of death

Then Frau Winckler would still live.”