Monastic Sisters On Their Deathbed: A Time To Remember

Monastic Sisters on Their Deathbed: A Time to Remember

This story is part of an ongoing series of editorials in which HMML curators and catalogers examine how specific themes appear across HMML’s digital collections. Examining the theme of “Death & Mourning,” Dr. Vevian Zaki shares this story from the Eastern Christian collection.

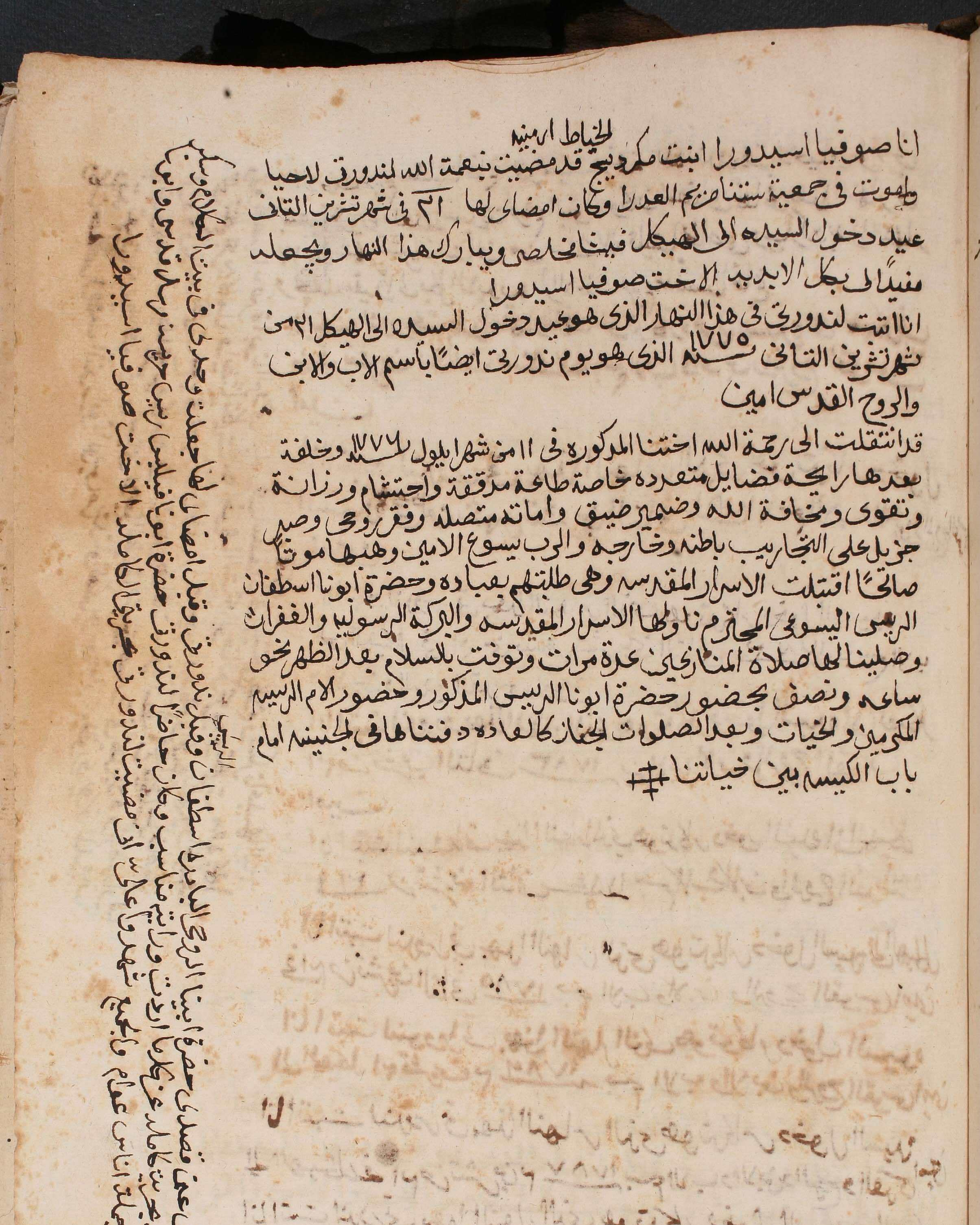

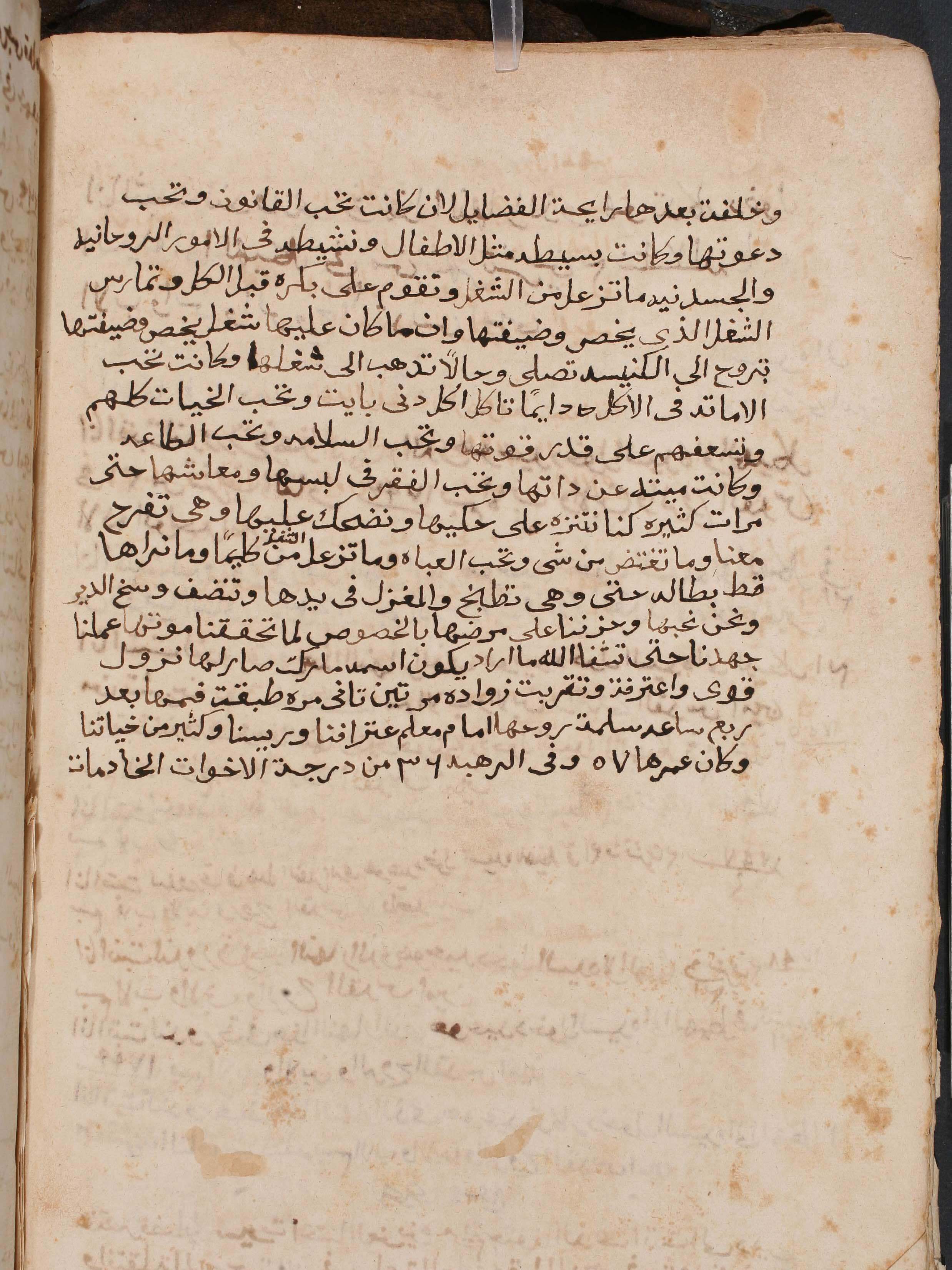

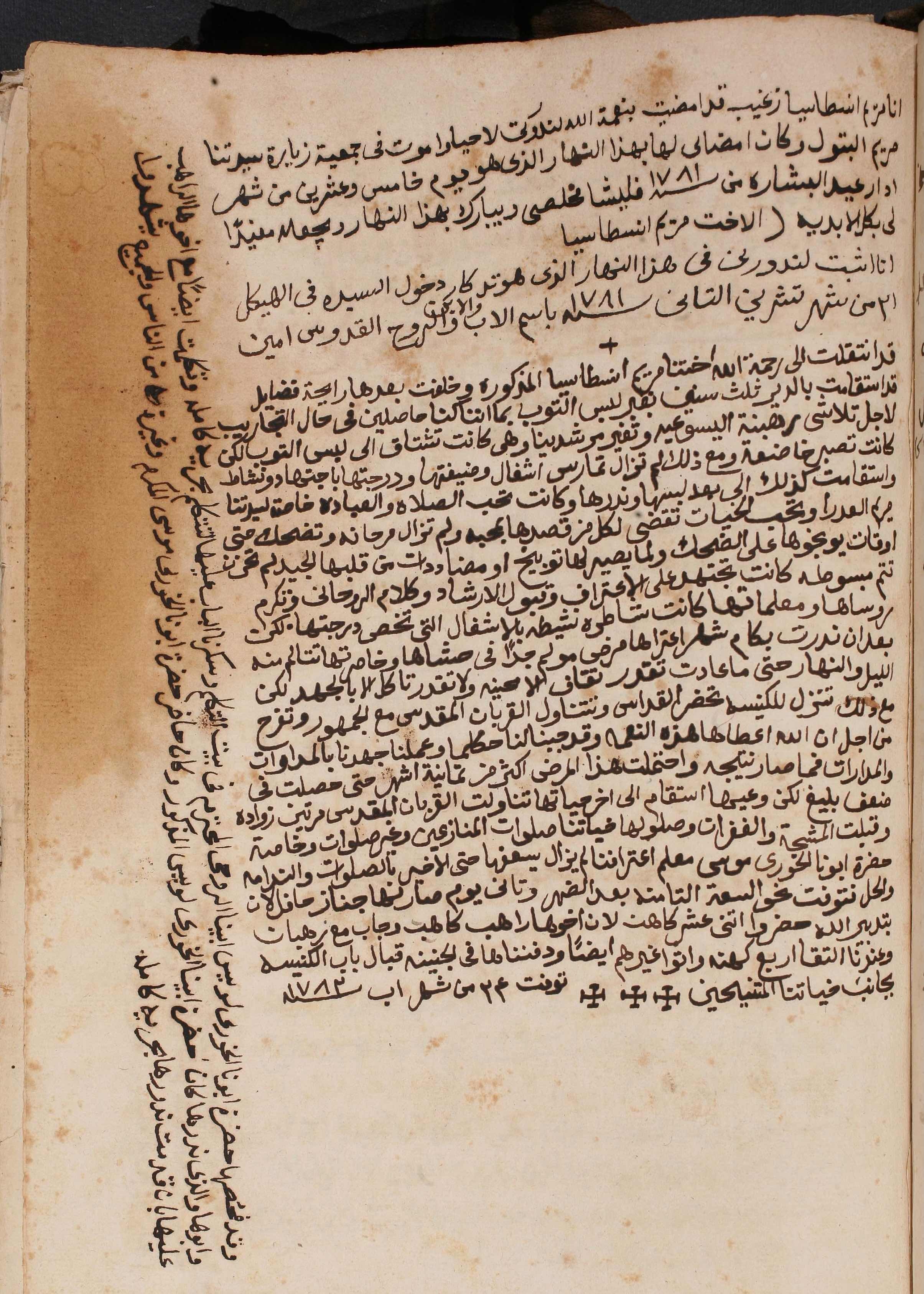

The book of vows contained in one manuscript (LMMO 00232) holds little of aesthetic appeal. It is written in a modest naskh script, by more than one hand, in a very dialectical 19th-century Arabic language. No illuminations or decorations are found in it. On the contrary, it is copied in a pragmatic way; when there is not enough space for writing, the text continues into the margins.

It does, however, include a treasure trove of information about the sisters of the Catholic monastery Dayr Ziyārat al-ʻAdhrāʼ. Starting with the monastery’s establishment by the Order of the Visitation of Holy Mary in ʻAynṭūrah, Lebanon, in the late 18th century, the book’s writing continues into the 1860s CE. For each sister of the monastery, the book records the vows that she took when she joined the Order, a confirmation of her taking these vows out of her free will, and an annual renewal of her vows for as many years as she lives. For some sisters, a tribute has been written posthumously that provides some information about her life and virtues and, most importantly for our story, about her death. Elsewhere I have given an example of a sister from the same book, discussing how her virtues and ministry were celebrated. In this story, I focus on how the book deals with the sisters in their final moments and after death.

A close reading of the biographies reveals that these women took great care to describe the last moments of their sisters’ lives. Information about the sister and her life before joining the Order, including her family, is documented whenever known. This information is better known for some sisters than others. However, for all of them, their last moments on their deathbed are well recorded, providing specific pieces of information about each sister. This includes the exact time of her death, not only in days, months, and years, but also in hours, and sometimes even minutes. Sister Mary Genova, for instance, passed away fifteen minutes after her last communion (folio 52v). Sister Martha Claudia is documented as passing away two and a half hours after noon (fol. 81r), while Sister Helena Margareta passed away three hours after midnight (fol. 16v).

The book of vows also consistently informs the reader of types and durations of ailments, such as for Sister Helena Antonia, who had a fever for eight days before her death in 1779 CE (fol. 59v), and Mary Francesca, who fell and had to crawl to church for one and half years before her death. The detailed descriptions also usually include the names of people who attended these last moments, the last rites administered for the sister, and whether or not she had time to confess and to receive the sacraments. Sister Sophia Isadora, for example, passed away in the presence of Father Stephan the Jesuit, the abbess, and many of the sisters (fol. 97r). She had the chance to receive the holy communion, the Apostolic benediction, and forgiveness. They administered the last rites several times for her, and she was buried in the garden of the monastery.

The description is usually combined with an acknowledgement of the virtues of the deceased sister, such as her spiritualism, the roles she performed in the monastery, and her patience during her sickness. These points were individually repeated for each sister as a kind of formality. However, for some sisters there was a clear personal touch: glimpses and hints here and there to show special connections, ties, and feelings for specific sisters. Some of these allude to the status of a sister among the community.

Take, for example, what was written about Sister Mary Genova. The detailed description of her death, which should have contained a report as witnessed for every other sister, could not help but reveal the emotions that were involved in the farewell:

“…We loved her, and we were sad when she was ill, in particular when we ascertained that she was dying. We did our best efforts to assist her recovery, but what God wills will be, may His name be blessed. [Her health] had strongly declined. She confessed and took communion twice. After the second time she closed her mouth, and fifteen minutes afterwards, she gave up her soul [to God] in the presence of our confessor, our abbess, and many of our sisters…”

Personalities and emotional connections are revealed in other insightful notes. Of Sister Mary Melanie, who died at the age of 60, they wrote, “She acted like a child. Even our [spiritual] guides used to call her ‘a child’” (fol. 32r). The community showed their care for Sister Sophia Catherine: “Because of her old age and disability, we were concerned about her lest she dies without receiving communion and the extreme unction” (fol. 55r).

A further aspect revealed in recording the deaths of these sisters is the prestige that some of them enjoyed, an aspect which prevailed in their death. For instance, the funeral of Sister Louisa Clara, one of the founders of the monastery and the cousin of the Metropolitan Mīkhāʼīl Khāzin, was attended by 25 priests (fol. 10r). Her nephews, monks, and various lay people also attended, as she was dignified among them. There is similar documentation for Sister Mary Anastasia, who died suddenly in 1783 CE. She had a large funeral attended by 16 priests, for her brother was a monk and brought 12 priests with him (fol. 101r).

Emotions such as love, fear, and care, in addition to social status, spontaneously emerged during the course of writing these death notices. While these were meant to be in memory of one deceased sister, they in fact endure as a testament to a whole community.