Instructions For Burial: The Last Will And Testament Of Ephrem The Syrian

Instructions for Burial: The Last Will and Testament of Ephrem the Syrian

This story is part of an ongoing series of editorials in which HMML curators and catalogers examine how specific themes appear across HMML’s digital collections. Examining the theme of “Death & Mourning,” Dr. James Walters shares this story from the Eastern Christian collection.

“I, Ephrem, am dying.”

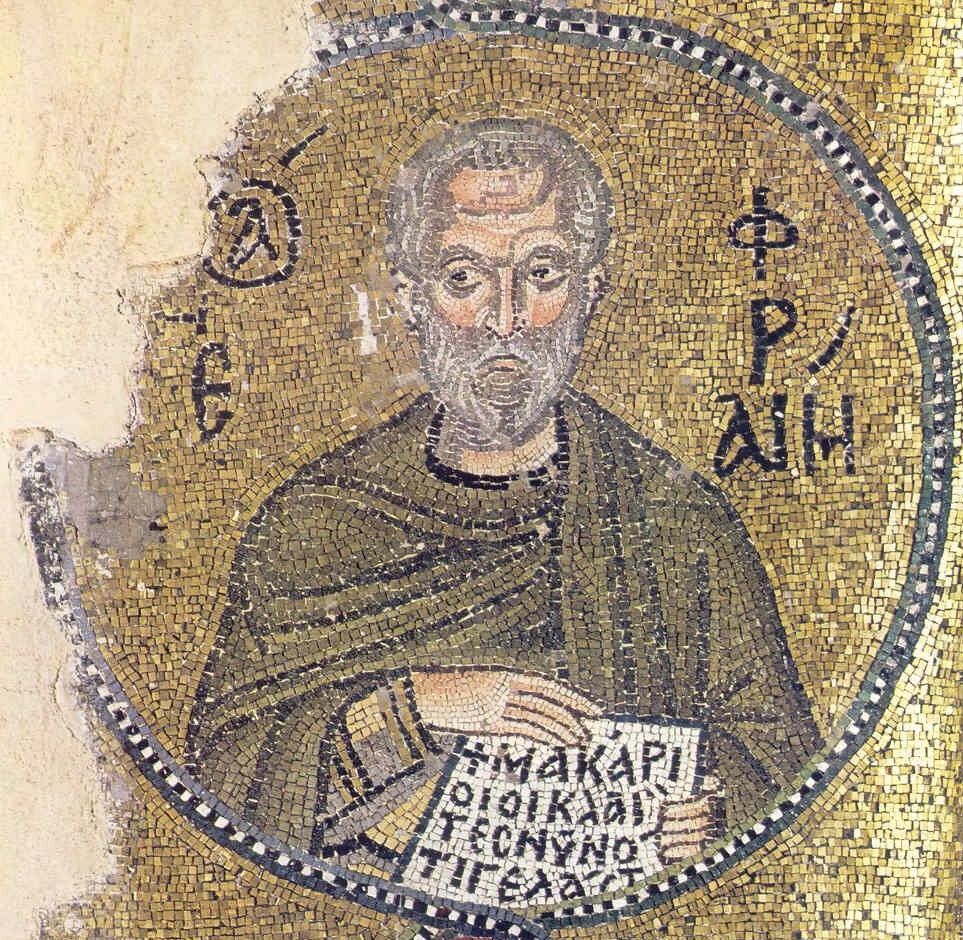

So begins a short Syriac poem attributed to the 4th-century author Ephrem the Syrian. Ephrem is perhaps the most widely known of all Syriac authors; his works (some genuine, some misattributed, and some spurious) have been translated into dozens of languages from late antiquity to the present.

Ephrem lived most of his life in the city of Nisibis (modern day Nusaybin, Turkey), but when that city was captured by the Persian king Shapur II in 363 CE, he—along with all the inhabitants of Nisibis—was forced to leave. He spent the final decade of his life in the nearby city of Edessa (modern day Şanlıurfa, Turkey).

Ephrem’s impact on the Syriac tradition is enormous, and his legacy pervades all aspects of Syriac literature and liturgy. He is most famous for composing madrashe, a Syriac term that is often translated simply as “hymns,” but which might better be translated as “teaching songs.” Indeed, Ephrem’s madrashe are like hymns insofar as they are metrical and poetic, but in terms of content they are often much more like dense theological treatises. Many of Ephrem’s madrashe are arranged in thematic “cycles” based on content, such as the madrashe on paradise, the madrashe on faith, and the madrashe on the nativity.

There is evidence from later Syriac authors that at least some of Ephrem’s teaching songs were performed in liturgical settings, likely by choirs of women. Even though the liturgical performance of these teaching songs ceased over time, there are many quotations of Ephrem’s works that found their way into the Syriac liturgies. Ephrem’s signature metrical style—paired lines of 7:7 meter—even persisted in Syriac literature, as later authors wrote new works “in the meter of Ephrem.”

Given the significance of Ephrem as a luminary in the early Syriac tradition, it is no wonder that later authors might have pondered what type of advice Ephrem might have provided at the end of his life. This type of speculation led at least one author to write an exhortation attributed to Ephrem, presumably while he was dying.

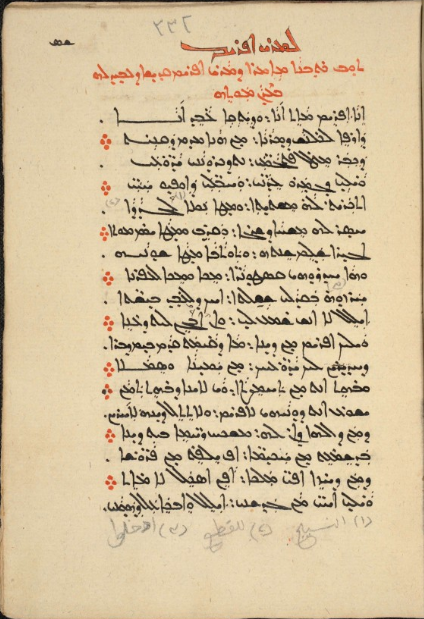

The Syriac title of the work is “A discourse of St. Ephrem which was made by him at the moment of his death.” But the work has also become more broadly known by the title Testament of Ephrem. (Note: regular readers of HMML stories may remember that the Testament of Ephrem was partially the subject of a story from our Fragments series.) The Testament of Ephrem is found in a number of manuscripts in HMML Reading Room, testifying to the popularity of the text.

So, what did this later author imagine that Ephrem would say to his followers? The text begins with Ephrem’s awareness of his impending death with a short series of poetic metaphors:

“The thread is cut short and therefore the web is nearly woven

The oil of the lamp is lacking, and the day of death has approached and arrived

The hired laborer has completed his season and the foreigner has come to his departure”

Then, somewhat surprisingly, a large portion of the author’s text is occupied with Ephrem providing instructions for his funeral. Seemingly aware of his own popularity, he begs his followers not to give him any special treatment after death:

“Do not place me with the martyrs, for I am a sinner and deficient

And because of my deficiencies I am afraid to be brought near their bones

For if straw approaches fire, it will burn and consume it

It is not that I despise their company, but because of my guilt I fear it”

Rather, with the humility becoming of a saint, he requests a simple burial and chastises anyone who would bury him otherwise:

“Anyone who places with me a cloak, may he be sent out into outer darkness

Anyone who places with me a vessel, may he burn in the fiery Gehenna

Bury me in my tunic and my cloak, for decoration is not fitting for the despised

Praise does not benefit the dead, for I am as sinner as I have said”

Later, this theme continues:

“Do not place sweet perfumes with me, for this honor is not befitting me

Neither incense nor perfume, for their scents do not benefit me

Make sweet scents in the holy place, and accompany me with prayers

Give incense to God, and over me speak the Psalms

Rather than the scent of incense, make supplication and pray for me”

The Ephrem depicted in the text even acknowledges that though he will be buried in Edessa, this is not his home, and he requests to be buried with other exiles:

“Do not place me in a box, for your decorations are not useful for me

I have a promise with my God, that I should be enshrouded with the foreigners

For I am a foreigner, like them, so place me with them, my brothers”

Many other topics are addressed, but these instructions for Ephrem’s funeral are interesting in a number of ways. First, through the admonitions of what not to do, the text likely provides some historical details about the ways that bodies were prepared for burial and how funerals were conducted in Edessa. Second, it provides a window into the ways that later audiences imagined their saints and what they valued. The insistence upon a simple burial without any special treatment is precisely the kind of pious humility one would expect of a holy person in late antiquity. And, as a final interesting note, while the text was certainly fabricated long after Ephrem’s death, it is possible that the real Ephrem in fact received no special burial, as there is no known site for his grave.