Feeling The Heavens

Feeling the Heavens

This story is part of an ongoing series of editorials in which HMML curators and catalogers examine how specific themes appear across HMML’s digital collections. Dr. Catherine Walsh looks at The Celestial in this story from Special Collections.

In summer of 1917, the New York-based artist Rockwell Kent made a bold decision. Accompanied by his 9-year-old son, Rockwell III (Rocky), the artist boarded a train to Vancouver, British Columbia. From there, they took a series of boats ever northward, finally arriving at remote Fox Island, in Resurrection Bay, Alaska, where they would live in a cabin of a trapper they befriended, Olson, for the next several months.

While there, Kent painted and drew, producing the artworks that helped make his career when they were exhibited at the Knoedler Galleries in New York in March of 1919. He also kept a journal, “added to from day to day,” and wrote letters to friends, which together served as the basis for his 1920 publication, Wilderness: A Journal of Quiet Adventure.

Wilderness includes much of what one might expect when two city-dwellers suddenly find themselves in the untempered hardships of an Alaskan winter: lists of the limited necessities they were able to pack, tirades against the harsh weather, and descriptions of the hard work required to caulk the cabin, provide firewood, and hold out against the cold and storms that loomed and threatened.

However, Kent was never shy about moving beyond the practical to embrace the philosophical aspects of existence. While he worked, he thought. In the evenings, he read Robinson Crusoe and Nietzsche, and he looked up at the night sky.

Kent never wrote about the scientific wonders of astronomy (a field that his son, Rocky, would later explore before devoting himself to physics). Instead, the night sky was an opportunity for contemplation, a vast field representing the majesty of nature and God...but an impersonal one, dwarfing human concerns and forcing the individual to confront himself.

In Wilderness, Kent references the night sky frequently, and indeed it must have seemed omnipresent during the short winter nights in Alaska, with none of the illumination of the city to interrupt the stars’ force. In the text, the stars receive a special report, their very presence so forceful as to merit a news bulletin on Wednesday, October 9:

“Midnight Bulletin: the stars are out, brilliant in a cloudless sky!” (Wilderness, p. 53)

The skies embrace the artist:

“Ah, how the cold, clean wind from the wide spaces then swept my soul, and how close about my head the dome of heaven and the stars!” (p. 183)

And the stars stand witness to his most private thoughts:

“It is close to midnight. I have one secret resolution to make for the new year and, that I may make it as earnestly and as truly as possible, the stars and the black sky shall be my witness. And so with the year nineteen hundred and eighteen I end this page” (p. 149)

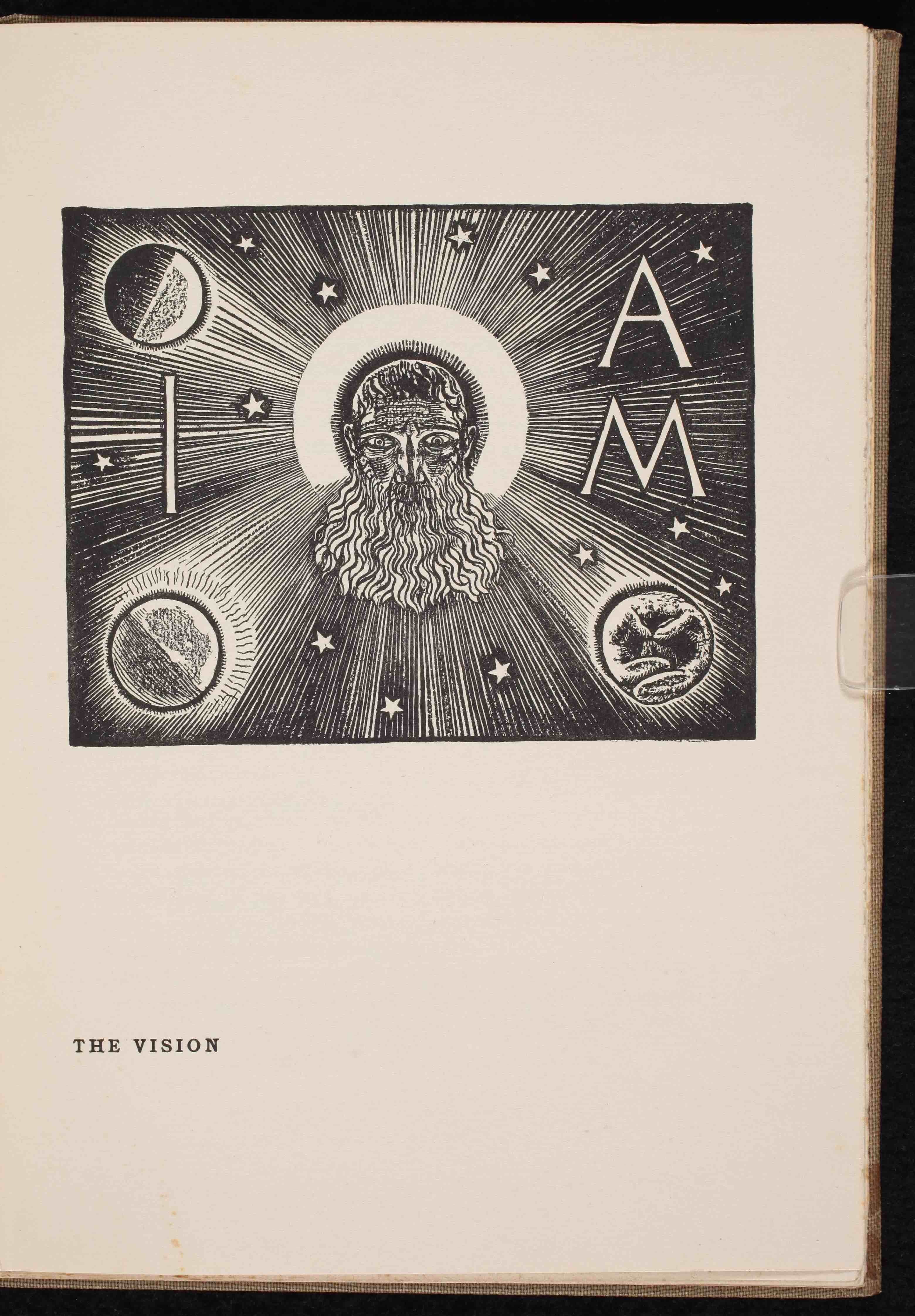

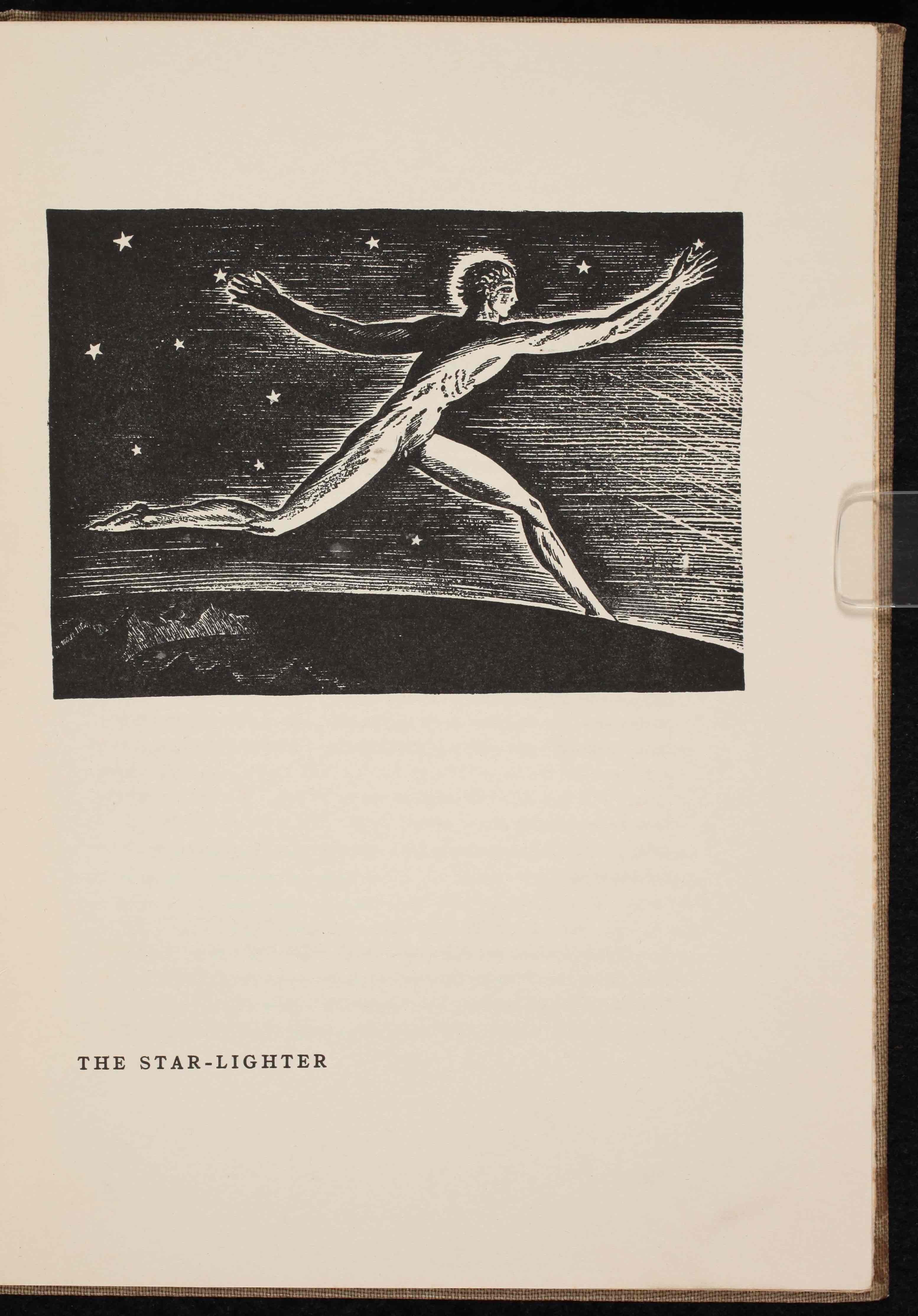

In the images for the 1920 publication, the night sky assumes an even greater presence. Kent’s images are not conventional illustrations; they are not explicitly related to the text on the accompanying pages. Instead, they present an additional entry point into the thoughts and experiences of the artist during his Alaska journey, and it is clear that the night sky is a character in its own right—one with ambivalent meaning.

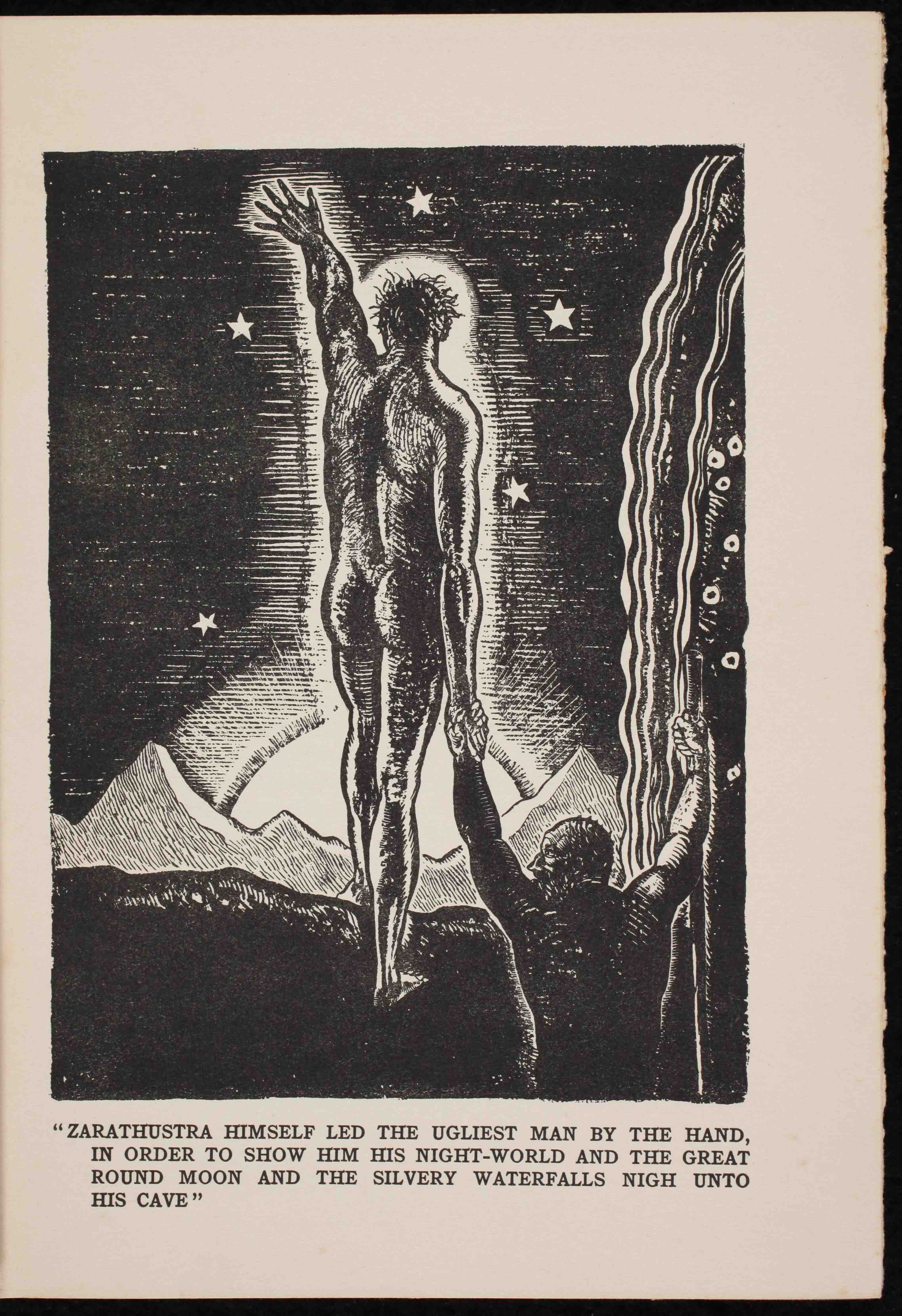

The first full-page image in the book illustrates not Rockwell’s own writing, but rather Friedrich Nietzsche’s Thus Spoke Zarathustra (1892). Here, the night sky is a revelation, a shining presence of promise that haloes the figure of Zarathustra as he leads the “ugliest man” out of darkness.

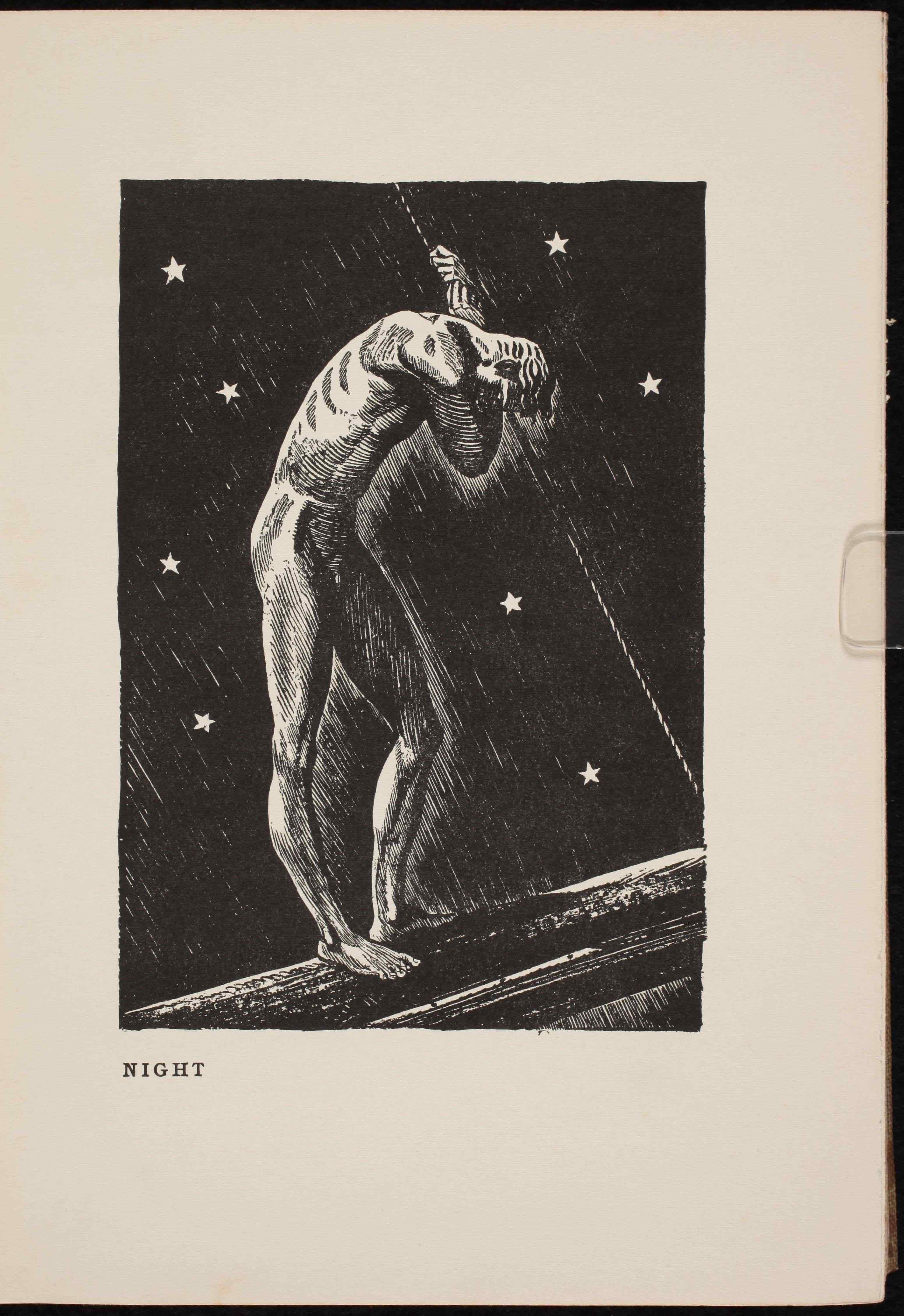

Yet, later, night is an oppressive presence, one that visibly weighs down the monumental figure at the center of the image.

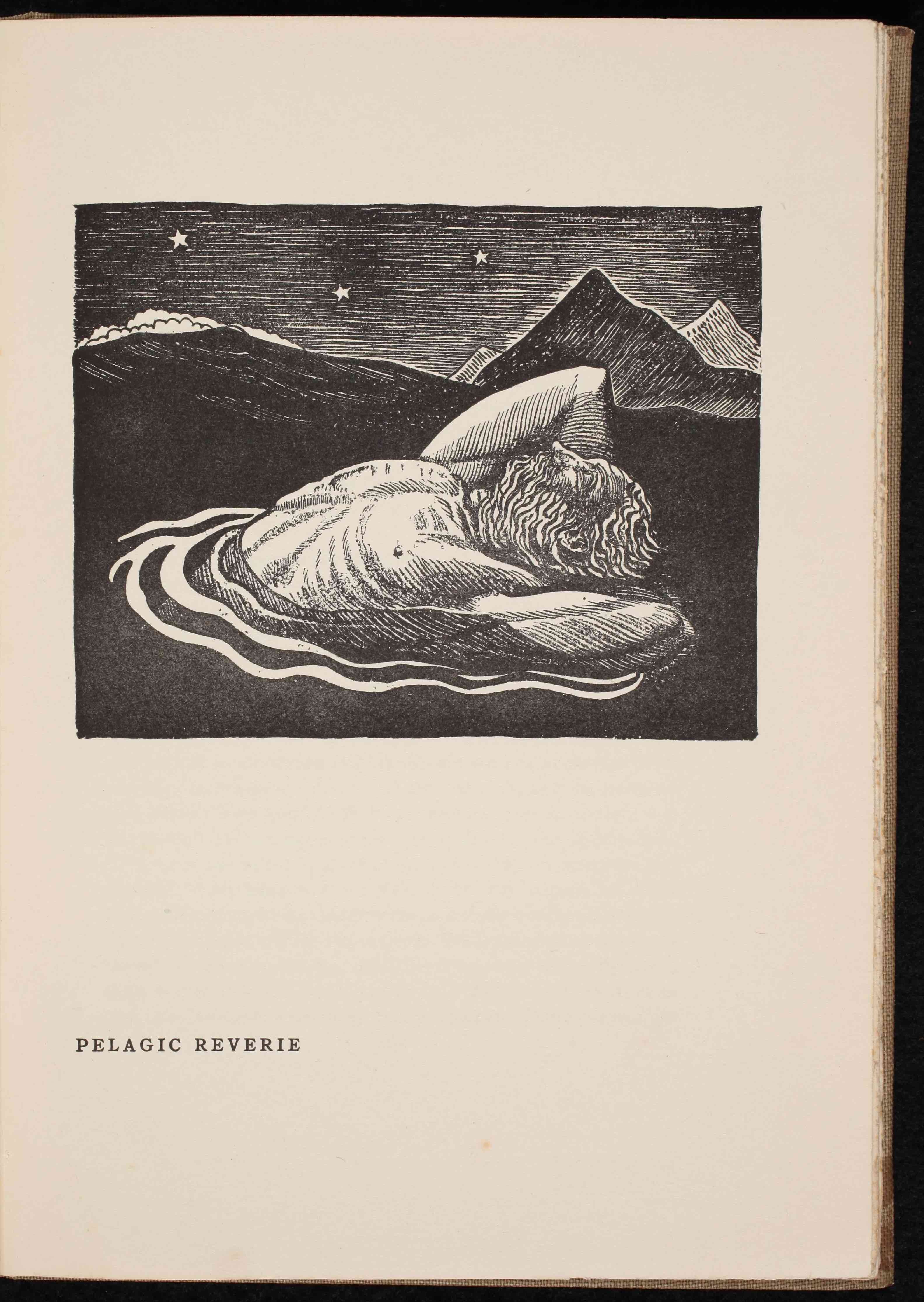

This alternating attitude towards the night sky appears again and again in Kent’s engravings for Wilderness. In Pelagic Reverie, a man with hands folded behind his head floats in a peaceful sea, gazing up towards the sky amidst swelling waves and climbing mountains that echo the curve of the man’s back. Here he is open to the sky, welcoming, and vulnerable, with eyes widely staring at the vision he beholds.

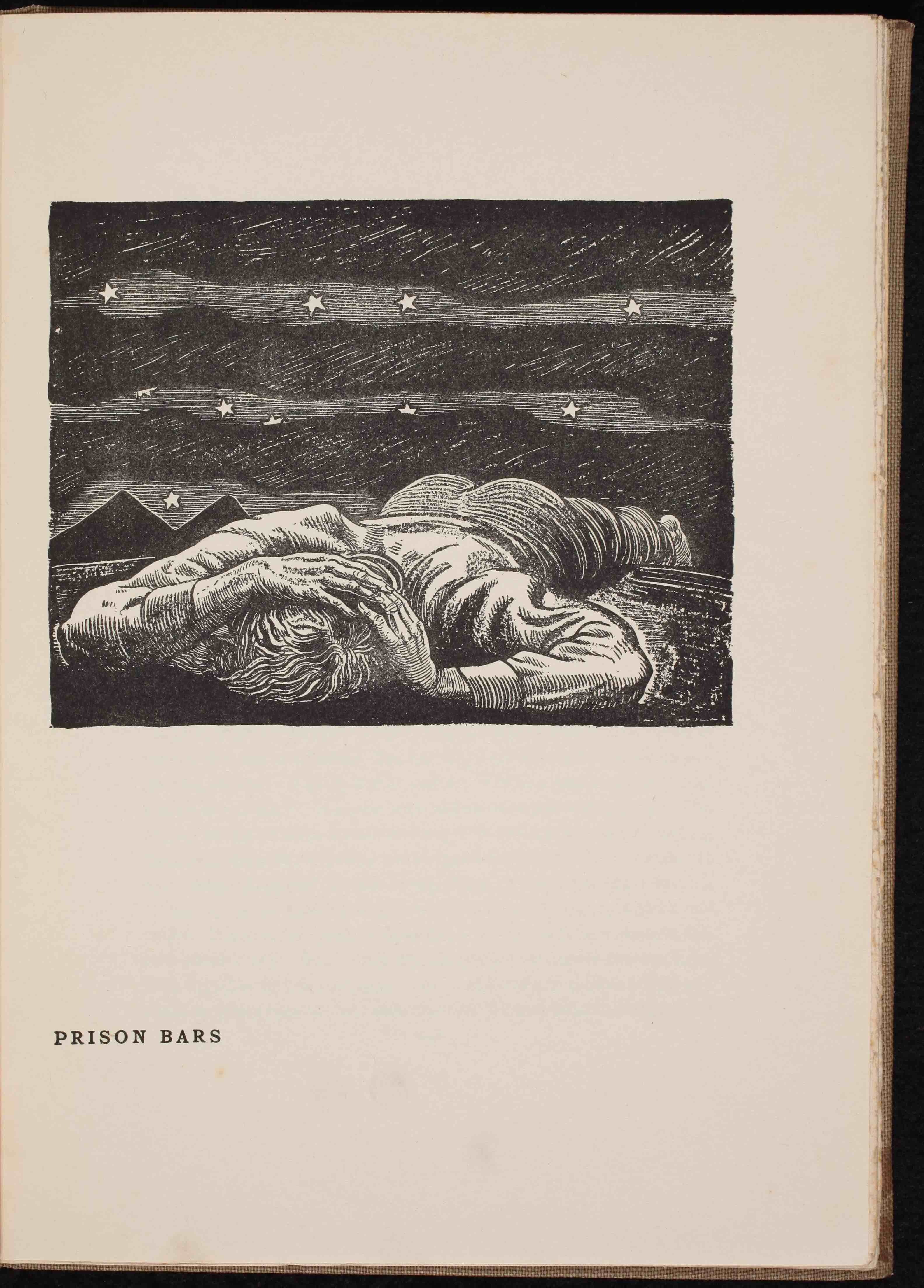

And yet mere pages later in Prison Bars, the night sky is once again a crushing force, with horizontal bands of stars appearing amidst clouds, their lines seeming to press down upon the prostrate figure below. This time, his crossed hands seem to protectively cradle his head, as if to ward off the visions he so eagerly welcomed in the previous image.

What is it about the night sky that can elicit such a dramatic and varied response?

The artist offers potential answers.

Kent reflected on his experiences in Alaska shortly before the end of his stay, writing about what the trip had meant to him and his son:

“It seems that we have both together by chance turned out of the beaten, crowded way and come to stand face to face with that infinite and unfathomable thing which is the wilderness; and here we have found OURSELVES—for the wilderness is nothing else. It is a kind of living mirror that gives back as its own all and only all that the imagination of a man brings to it. It is that which we believe it to be. So here we have stood, we two, and if we have not shuddered at the emptiness of the abyss and fled from its loneliness, it is because of the wealth of our own souls that filled the void with imagery, warmed it, and gave it speech and understanding. This vast, wild land we have made a child’s world and a man’s.” (p. 191–192)

Perhaps, in light of these words, one could interpret the night sky as a mirror that forces the viewer to confront himself. This might be a tranquilly contemplative experience, the “quiet adventure” described in the book’s subtitle. Alternatively, the self can be a frightening realm to explore, filled with loneliness and “the emptiness of the abyss.”

Kent’s engravings offer another, related possibility. In The Vision, the night sky houses a God-like haloed presence, surrounded by stars and proclaiming in aggressively large letters, “I AM.” Is this meant to be a vision present in the sky above, which might cause one to waver between marveling and cowering?

Kent’s reflections on his life in his autobiography, It’s Me O Lord (1955), published decades later, seem to support this interpretation. Here he contemplates God, analyzing his own thoughts and relationship with the notion.

“Often in writing, often in speech, I use the name of God. Yet it is neither as a ‘believer’ that I use it, nor in vain: God has become to me the symbol of the life force of our world and universe; a name for the immense unknown. Imponderable, yet immanent in man, in beasts and birds and bugs, in trees and flowers and toadstools, in the earth, sun, moon and stars. It—I choose the impersonal pronoun as alone consistent with my faith—It was to me a force as un-moral as such manifestations of itself as storms or earthquakes, and for that very reason greatly to be feared. It was as un-moral and impersonal and splendid as its sunset’s light on land and sea—and for that reason to be reverenced. I feared and reverenced God. In fear and reverence I painted. That mood forbids defining art as self-expression.” (p. 138)

If the night sky represents these two poles, fear and wonder, it is with wonder that Kent ends the text. The Star Lighter presents a hopeful, active vision, as an elongated and dynamic figure races across the surface of the earth, creating the stars.

Further Reading:

Constance Martin, Distant Shores: The Odyssey of Rockwell Kent (Chesterfield, MA: Chameleon Books, Inc., 2000).

Rockwell Kent, It’s Me O Lord: The Autobiography of Rockwell Kent (New York: Dodd, Mead & Company, 1955).

Rockwell Kent, Wilderness: A Journal of Quiet Adventure in Alaska (New York: G. P. Putnam's Sons, 1920).