Ḫeruy Walda Śellāsē’s “history Of Ethiopia”

Ḫeruy Walda Śellāsē’s “History of Ethiopia”

This story is part of an ongoing series of editorials in which HMML curators and catalogers examine how specific themes appear across HMML’s digital collections. From the Eastern Christian collection, Ted Erho shares this story about Banned Books.

Printing reached Ethiopia rather late. In Europe, texts were occasionally printed in Ethiopic characters from the sixteenth century onwards, but it was not until the nineteenth century that printing presses seem to have been used within Ethiopia itself. Even then, they were the domain of foreigners, especially missionaries who produced religious books in native languages in order to further their activities. Only at the beginning of the twentieth century did indigenous Ethiopian printing arise.

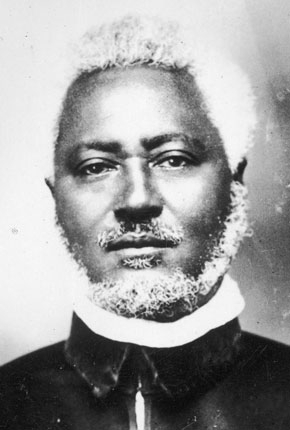

During its early days, perhaps no Ethiopian better understood the possibilities of this emergent technology, and utilized them more, than Ḫeruy Walda Śellāsē. One of the leading political figures of his era, he quickly rose through the governmental ranks, serving as acting mayor of Addis Ababa from 1919–1921 and ultimately as Foreign Minister of Ethiopia from 1931–1936.

Though best-known for his government service, Ḫeruy was also an important intellectual, and in this capacity began to leverage the new medium of printing to an unprecedented extent, publishing more than twenty books. In contrast to the prevailing trends of his day wherein the vast majority of printed texts were either editions of Ethiopian Orthodox Church works or government documents, Ḫeruy Walda Śellāsē published an unusually diverse range of literature—from fiction to travelogue to biography to history—writings often aimed at broader audiences.

Around 1928, Ḫeruy laid the groundwork for his most ambitious project by publishing a Prelude (ዋዜማ) to a larger text he was preparing: a History of Ethiopia. This would not be the first major historiographical work authored by an Ethiopian in Amharic (one of the most widespread modern Ethiopian languages), as writings like Aṣma Giyorgis Gabra Masiḥ’s Yagāllā tārik (History of the Gāllā) and Takla Iyasus Wāqğerā’s Goğğām Chronicle had appeared over the preceding decades. Nor would it be the first indigenous history of the nation, for Ge‘ez (Classical Ethiopic) chronicles could be found in libraries of a few churches and monasteries. By virtue of the fact that it would be printed rather than copied by hand, it would, however, be the first comparatively widely-accessible indigenous history of Ethiopia in a native vernacular. By the mid-1930s, all but the final few pages of the volume had been typeset and printer’s proofs had been prepared. Publication of Ḫeruy Walda Śellāsē’s History of Ethiopia was imminent.

Yet, by the mid-1930s, storm clouds had been gathering for some time. In 1922, Benito Mussolini had marched on Rome and seized control of the Italian government. After spending the next decade “pacifying” Libya by extreme means, fascist Italy turned its attention to the only African country that had entered the twentieth century as an independent nation—the site of Italy’s defeat forty years earlier—and attacked Ethiopia in October 1935. Another brutal campaign followed in East Africa.

As Italian troops entered Addis Ababa in May 1936, Ethiopian Emperor Ḫāyla Śellāsē fled to England accompanied by his family and a few trusted advisors, including Ḫeruy Walda Śellāsē. The invaders subsequently decreed that the History of Ethiopia, which had by then already begun to be printed, could not be published. Indeed, such a book opposed fascist and colonialist aims and ideals; the existence of a modern History of Ethiopia, written by an Ethiopian, was a threat to Italian hegemony over the region. The sheets that had already been printed were sold off to local merchants as wrapping paper.

Five years later, Ḫāyla Śellāsē re-entered Ethiopia as a combination of Ethiopian and Allied forces pushed the Italians from the country. Ḫeruy Walda Śellāsē, however, did not survive the exile, dying in England at the age of 60.

Yet, despite the attempts to eliminate it, Ḫeruy’s History of Ethiopia was not equally moribund. At least one partial set of printer’s sheets for the work survived, today housed at the Frobenius-Institut in Frankfurt, Germany. Another set might be at the Institute of Ethiopian Studies in Addis Ababa. And at least some printed pages seem to have been in the possession of another eminent Ethiopian civil servant and scholar, Marseʻē Ḫazan Walda Qirqos, in the mid-twentieth century.

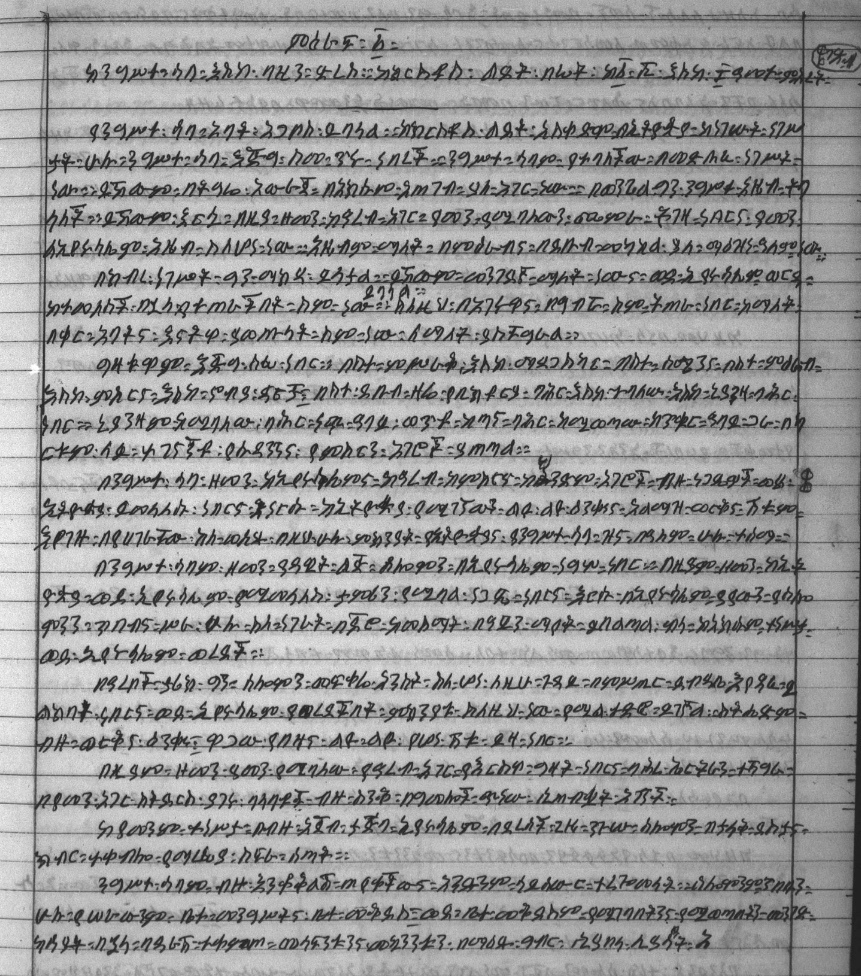

But these are not all. Recognizing the importance of Ḫeruy Walda Śellāsē’s History, various individuals began making copies of the text by hand, in accordance with longstanding Ethiopian practice—an unusual reversal for a document that had been set to become the first printed work of its kind.

At least three handwritten copies are known from the Ethiopian Manuscript Microfilm Library: one in the library of dağğāzmāč Kabbada Tasammā, completed in early 1948 (no. 5399); one partially copied by Marseʻē Ḫazan Walda Qirqos (no. 3651), and a photocopy of a third in the Institute of Ethiopian Studies (no. 1504). Through these labors a network of copies was slowly built up, not only allowing the History of Ethiopia to be read and used but ensuring that it would never again reach the precipice of extinction.

Seventy years after its original intended release, Ḫeruy Walda Śellāsē’s History of Ethiopia finally appeared in print via the efforts of one of his descendants, Śannāyt Takla-Māryām, who compiled and published an edition in 2006–2007.

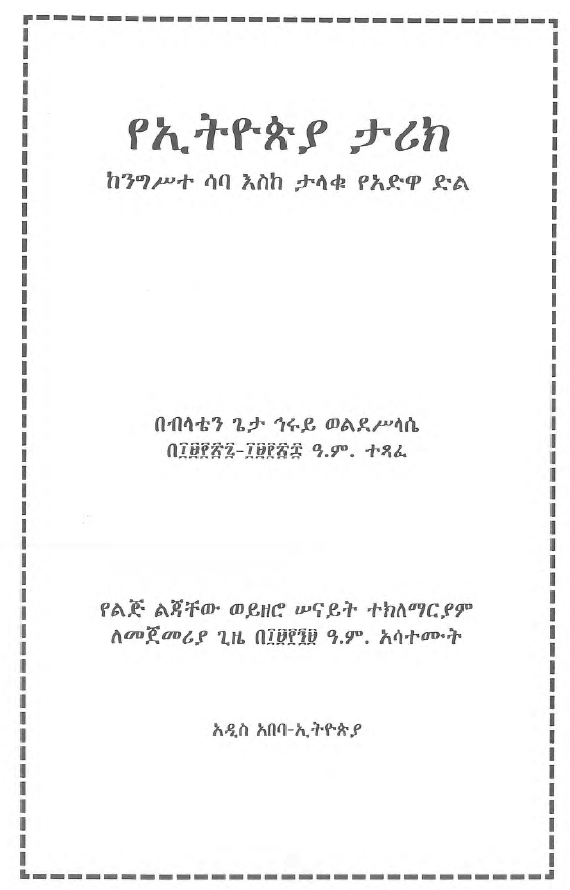

Precisely what Ḫeruy Walda Śellāsē intended his History to be called remains something of an enigma, with several different forms appearing over the years, including Tārika nagaśt (History of the kings) in the 1978 doctoral dissertation of prince Asfa-Wossen Asserate, wherein several chapters of the text were published for the first time. Nonetheless, it is the title of Śannāyt Takla-Māryām’s edition, Yaʼityopyā tārik (History of Ethiopia), that accords most closely with the earliest scholarly formulations. This is the title by which Ḫeruy Walda Śellāsē’s work was recently registered by HMML with the Library of Congress, creating another official record to help ensure that this groundbreaking piece of indigenous African historiography will neither be lost nor forgotten.