What Are The Animals Trying To Tell Us?

What Are The Animals Trying To Tell Us?

This story is part of an ongoing series of editorials in which HMML curators and catalogers examine how specific themes appear across HMML’s digital collections. From the Islamic collection, Dr. Ali Diakite and Dr. Paul Naylor have this story about Animals.

In historical Timbuktu—as in any part of the pre-modern world—animals were ubiquitous. Even today, the sounds of camels, donkeys, goats, dogs, roosters, and songbirds can be heard alongside the more modern cacophony of Mali’s urban life. In reviewing HMML’s collections of manuscripts digitized in Timbuktu, it is clear that many sought to rationalize and make meaning from these animal sounds.

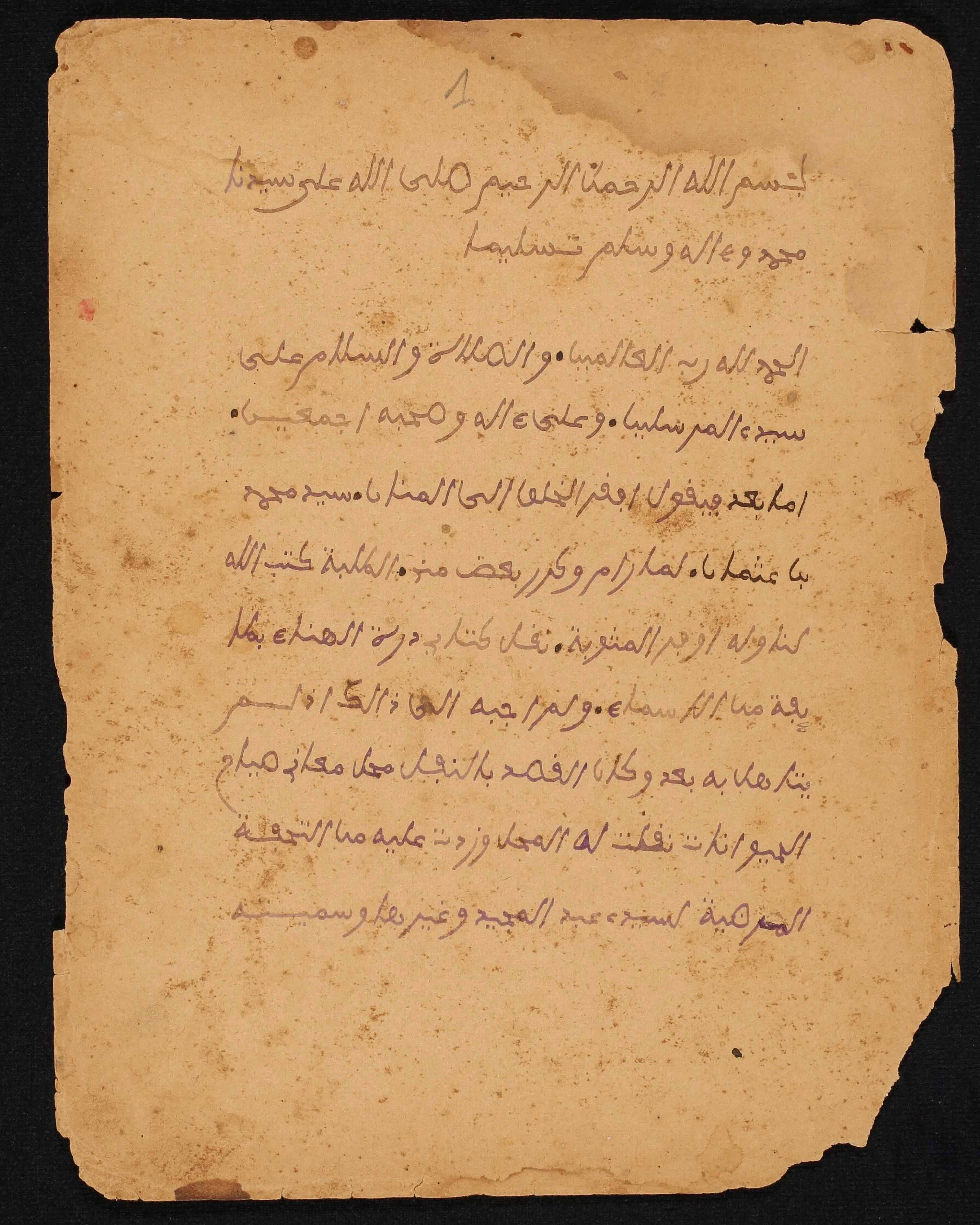

Muḥammad ibn ʻUthmān authored treatises and poems on semantics, vocabulary, and pedagogy throughout the 1920s and 1930s. One of his compositions, al-Tibyān fī maʻānī ṣiyāḥ al-ḥayawān, is dedicated to “translating” the sounds of various animals, abridged from a longer treatise of his on the subject. He begins it like this:

“Among the essential knowledge that the Blessed and Almighty God bestowed upon our master Muhammad, prayers and peace be upon him, was knowledge in the languages of all the creatures, the totality of animate and inanimate things, no matter how high or low, whether spiritual or base. And how could it not be, for he—prayers and peace be upon him—is the Messenger for all creation.”

With this in mind, Muḥammad ibn ʻUthmān lists various animals and what their cries are trying to tell us. Here is a selection of excerpts from the text:

“The fox: Oh apportioner of blessings, make me satisfied with what you have apportioned me!”

“The rooster: Remember God, Oh ignorant ones!”

“The vulture: Son of Adam, live as you prefer but indeed you are dead!”

“The sparrow: Oh Knower of Secrets, Remover of Tragedies, give me the crop of whoever fails to obey You!”

“The sandgrouse: He who stays quiet is saved.”

These “translations” of animal sounds into human speech are linked to observations of each animal’s characteristics. Sparrows are an agricultural pest, vultures eat carrion, and sandgrouse make little noise. But the animals’ cries are also meant to prompt feelings of piety. Someone rudely awakened by the crowing of a rooster should not curse the bird, but instead recall God. And someone who loses his animals to a fox should thank God for the other things that they have.

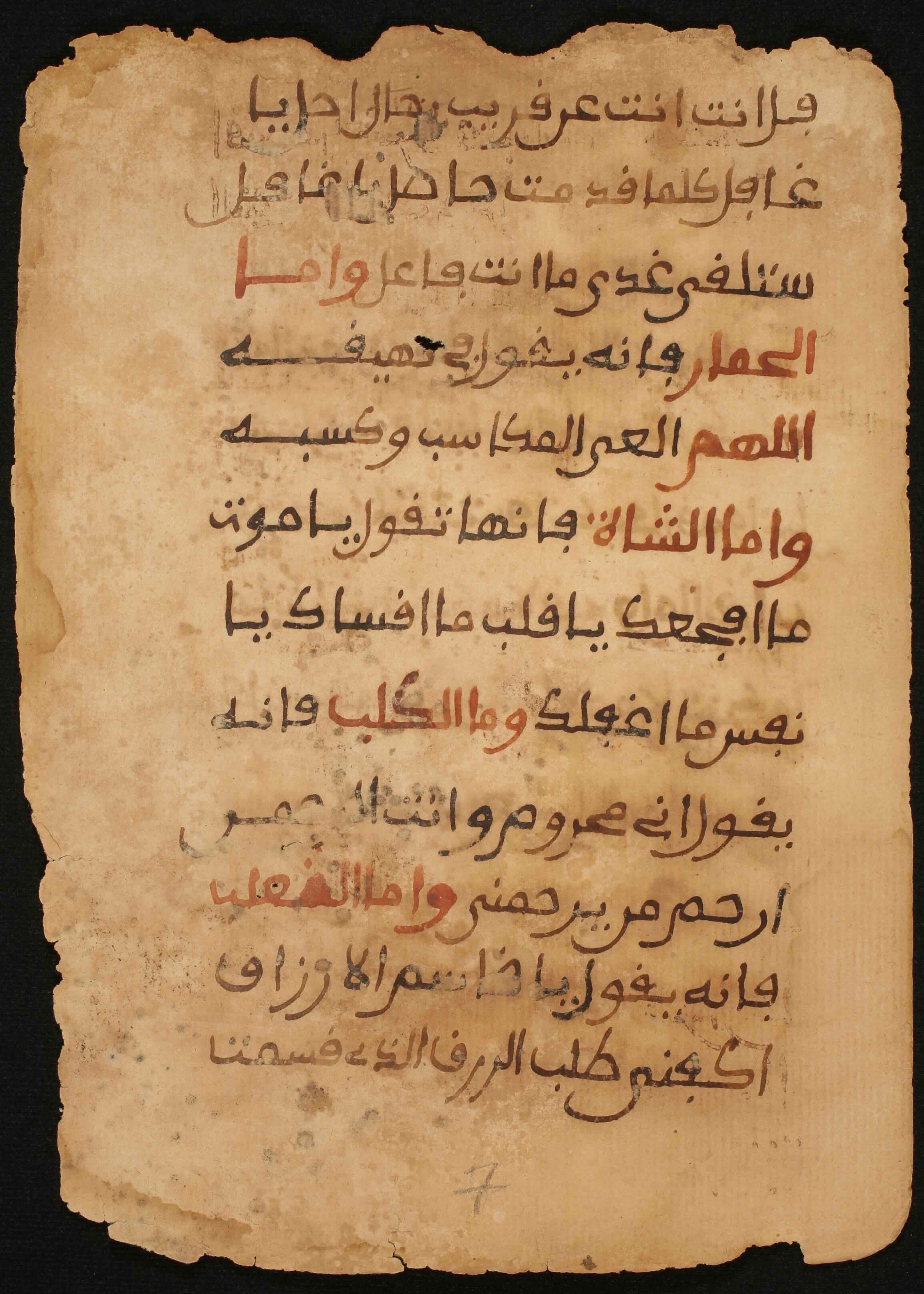

The cries of animals also feature in a story from the “Exploits of Ali” genre, which we mentioned in a previous Editorial. In this story, the Jews of Khaybar (in present-day Saudi Arabia) ask Ali, the Prophet’s cousin and son-in-law, a series of seemingly impossible questions:

“Tell us what the horse says with its neighing, what the camel says with its bellowing, what the cow says with its lowing, what the donkey says with its braying, what the sheep says with its bleating, what the dog says with its barking, what the fox says with its howling, what the eagle says with its crying, what the crow says with its cawing, what the kite says with its screeching, and what the dove says with its cooing; about the fire and what it says with its burning, the wind and what it says with its blowing, the water and what it says with its roaring, the frog and what it says with its ribbiting, the hoopoe bird and what it says with its calling, the chicken and what it says with its clucking, the hedgehog and what it says with its snuffling, the sparrow and what it says with its chirping, the nightingale and what it says with its singing, and the turkey and what it says with its gobbling.”

Strangely, Ali’s answers mirror exactly those reported by Muḥammad ibn ʻUthmān, suggesting that there was wide agreement about what these animals were saying!

The extent to which these ideas were present in popular culture is clear from an account of the 1755 Lisbon earthquake by an otherwise unknown author, Aḥmad ibn Bindād al-Māsinī (his account of the earthquake was also featured in a previous Editorial). While al-Māsinī mentions the terrifying sounds and shaking of the earthquake itself, most of his account involves the reactions of animals and what, in his opinion, their sounds meant:

“And the creatures of the sea emerged from their depths, stuttering ‘God be Praised,’ ‘Glory to God Most High.’ The flies buzzed in the corners of the houses, crashing into each other, glorifying God, venerating God, and confirming the oneness of God. The hornets and crickets sang in the houses and outside, glorifying God and venerating God, while the beasts ran in all directions, trembling and raising their heads to the sky, glorifying God, venerating God, and confirming the oneness of God, as we witnessed with our own eyes. Meanwhile the birds were unable to fly and began to tremble due to them glorifying God, venerating God, and confirming the oneness of God.”

Perhaps the author is influenced by the general Muslim belief, outlined in the Qur’an, that all creatures are engaged in glorifying God:

“The seven heavens, the earth, and all those in them glorify Him. There is not a single thing that does not glorify His praises—but you cannot comprehend their glorification. He is indeed Most Forbearing, All-Forgiving.”

(Sūrat al-Isrāʼ, Verse 44)

Then this would be, naturally, how al-Māsinī interpreted the behaviors that he saw following the earthquake.

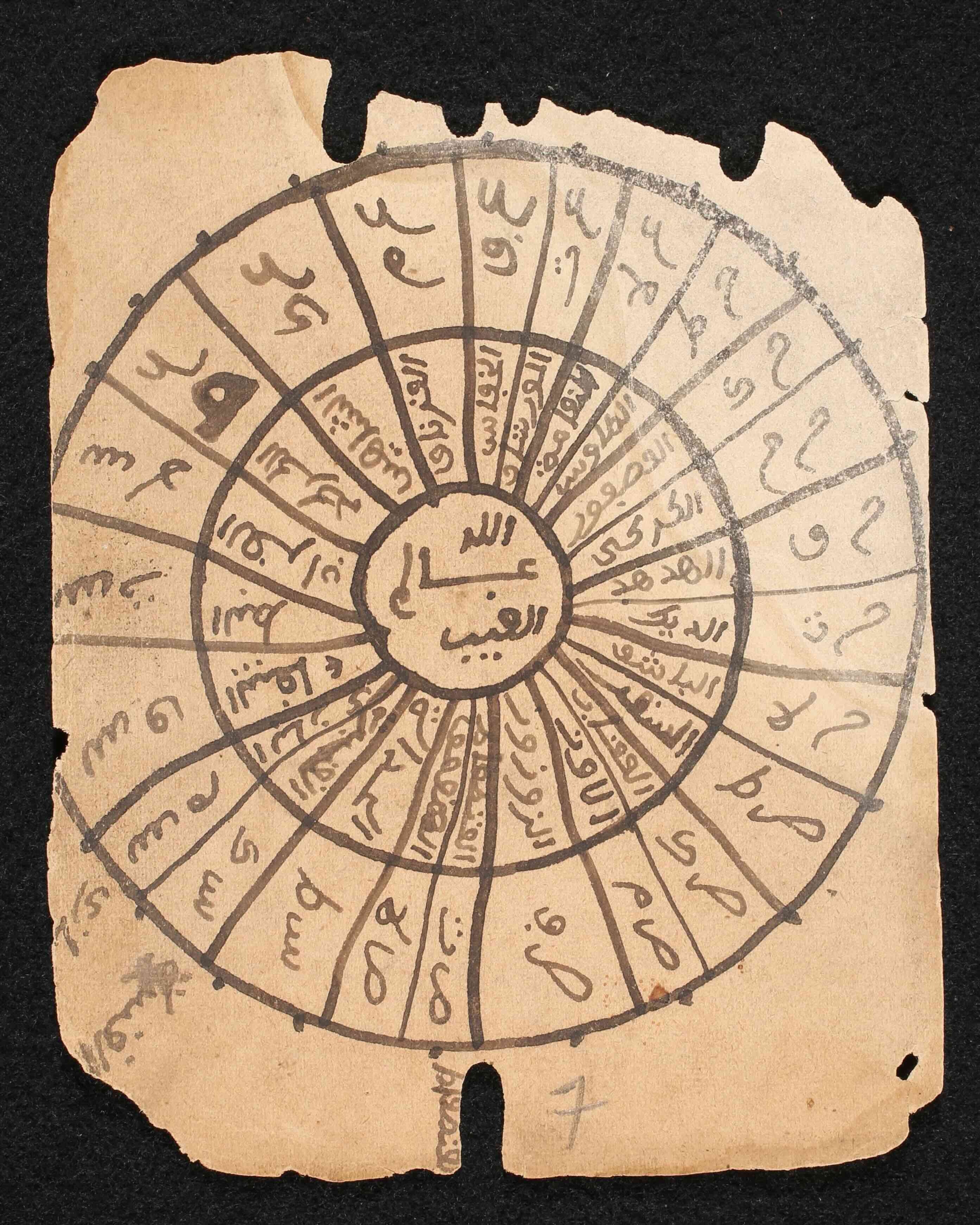

We also find various texts in which animals’ cries herald future events. The Mamma Haidara Library contains multiple copies of a treatise on divination using the howl of a wolf. For example, “if the wolf howls five times it means that there will be much rainfall and the crops will do well,” whereas “if the wolf howls six times it means that the wealth of the country will disappear and homes will be consumed by strife” (SAV BMH 35822). Another manuscript, ELIT AQB 01575, contains a more complex treatise on divination that is divided into chapters using the names of a wide variety of birds.

Due to desertification and a changing climate, species loss has been more rapid in the Sahel region of Africa than in other parts of the world. Far from viewing animals only as a source of food and labor, these works remind us of how popular beliefs about animals impacted the intellectual life of the scholar and, in fact, elevated the animal to an important repository of beneficial knowledge. Most people in the Sahel still live in close proximity to animals, and their daily life is punctuated and enriched by animals’ sounds and observations. Let us hope that the messages they have for us continue to be heard.