Like A Dog

Like a Dog

This story is part of an ongoing series of editorials in which HMML curators and catalogers examine how specific themes appear across HMML’s digital collections. From the Islamic collection, Dr. Josh Mugler has this story about Animals.

In Arabic literature, as with many cultures, dogs are viewed with some ambivalence. They are praised for their loyalty and usefulness yet are held at a distance due to their dirtiness and the potential danger of their teeth and claws. There are, however, favorable accounts of dogs, some of which reach heroic proportions.

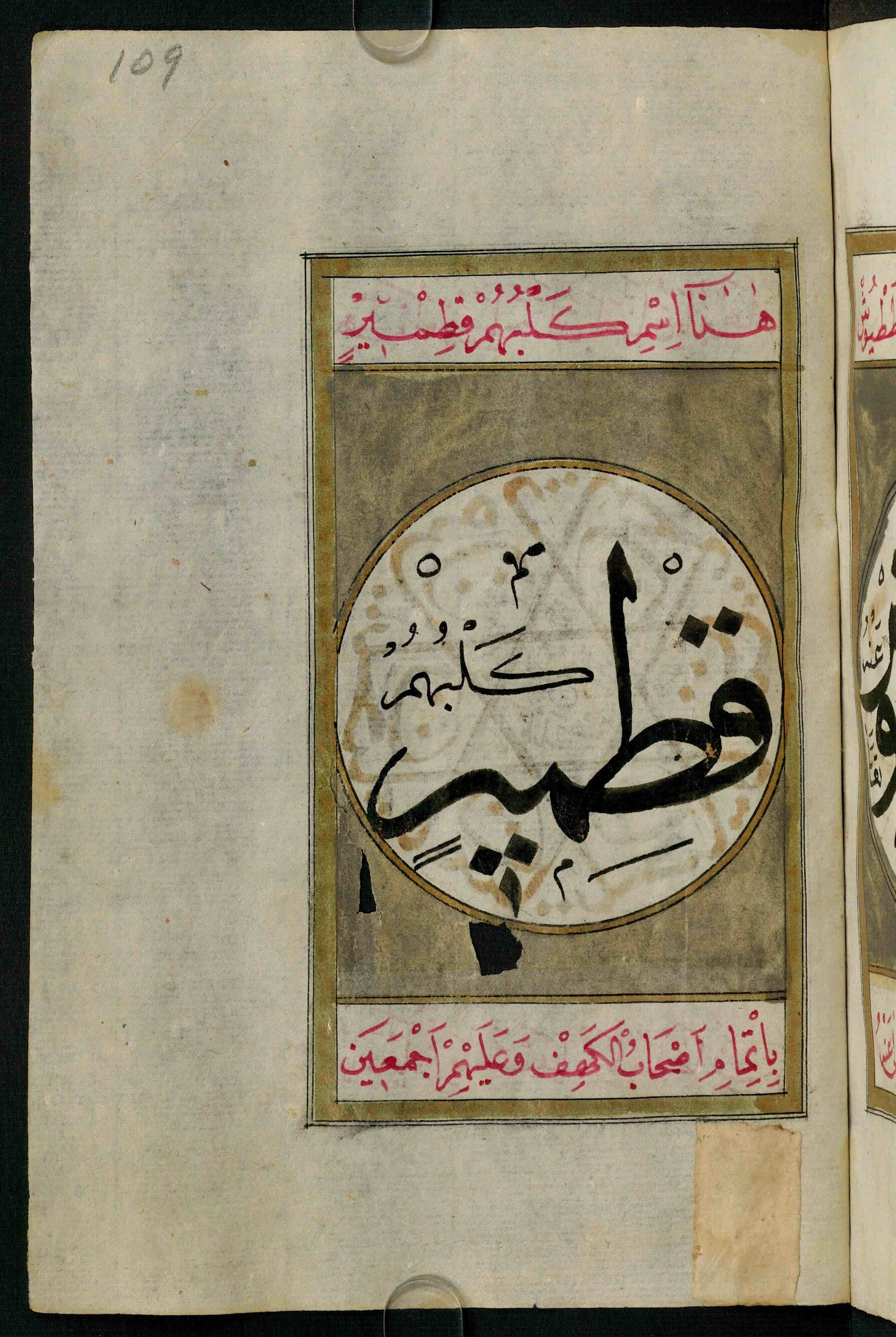

While some records of the Prophet Muḥammad’s sayings and deeds (hadith) counsel Muslims to avoid having dogs in their houses, other hadith teach that every living creature, including dogs, should be shown kindness. For example, one hadith tells the story of a sinner who was forgiven because of an act of kindness to a thirsty dog. The Qurʼan also mentions the story of the People of the Cave (ahl al-kahf), known in the Christian tradition as the Seven Sleepers of Ephesus, who were guarded by their dog as they miraculously slept in a cave for several centuries (al-Kahf 18:18, 22). This story was so fascinating to later Muslims that the dog, whose name was passed down as Qiṭmīr, was believed to have supernatural protective qualities and was invoked in prayer books, along with his human companions.

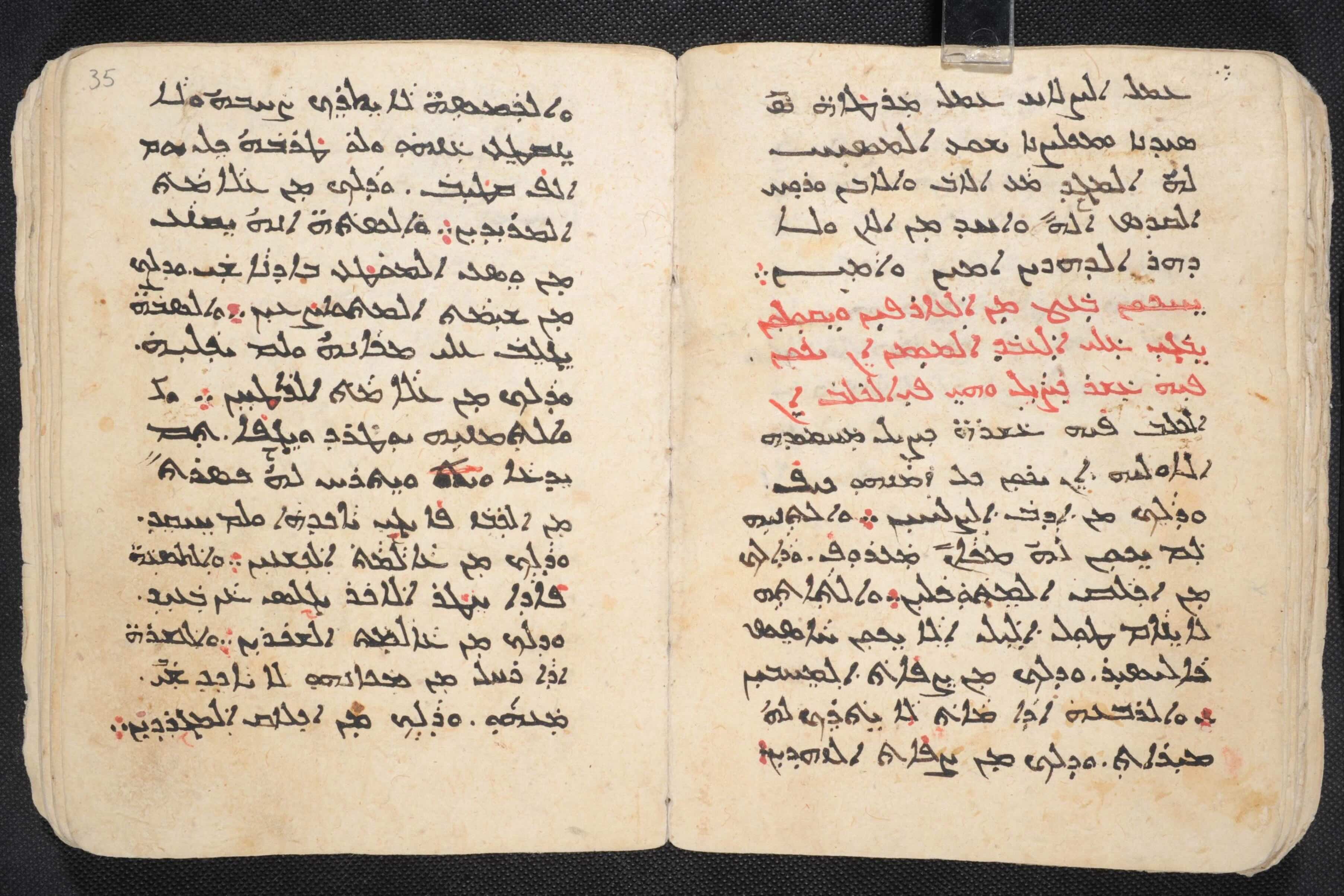

The characteristics of dogs have also served useful metaphorical and rhetorical roles in Arabic literature. The most famous Islamic text concerning dogs is Muḥammad ibn al-Marzubān’s (d. 921 CE) Faḍl al-kilāb ʻalá kathīr mimman labisa al-thiyāb, or “The superiority of dogs over many of those who wear clothes,” in which he laments the alleged moral decay of human society in 10th-century Baghdad (see USJ 2 00547). In a similar vein, an anonymous Christian author left us a short Arabic text describing 10 characteristics of dogs that are necessary for a faithful servant of God to imitate; this text is found in at least three manuscripts in HMML’s collections digitized in Mardin, Turkey.

From the earliest centuries of Arabic grammatical and lexicographical scholarship, a favorite exercise for scholars of the language has been to display the richness of Arabic vocabulary by collecting numerous terms that refer to a single concept or theme and unpacking the nuanced distinctions among them. Dogs were one of many such vocabulary fields and, just as in English (hound, pup, pooch, mutt, and so on), Arabic has numerous terms to refer to dogs and their various types. One lengthy treatise focuses entirely on defining these terms, written by Muḥammad ibn al-Khiyamī (1155–1245 CE). HMML has photographed one copy of this work (USJ 2 00242), which was copied in Damascus, Syria, in 1921 by the scribe Muḥammad Ṣādiq.

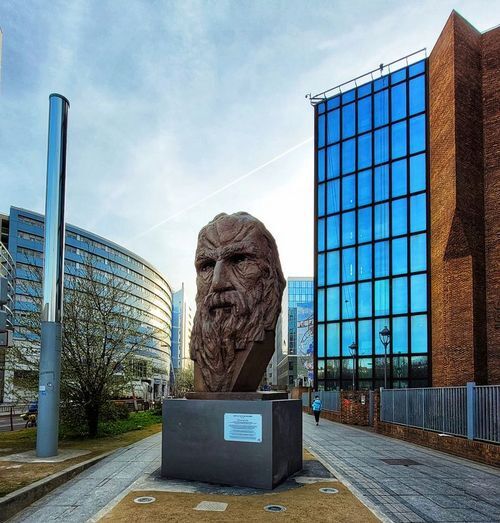

In fact, canine lexicography plays a major role in a famous anecdote from 11th-century Baghdad, involving the poet Abū al-ʻAlāʼ al-Maʻarrī (973–1057 CE). The poet was widely known as a vegan and animal lover, to the point of being rather misanthropic in his poetry. He had been blind since contracting a serious case of smallpox at a young age. According to legend, while attending a crowded social gathering, al-Maʻarrī tripped over the foot of another guest, who angrily turned and roared, “Who is this dog?” Not missing a beat and supremely confident in his mastery of the Arabic language, al-Maʻarrī responded, “The true dog is the one who does not know 70 names for ‘dog.’” This scholarly challenge has haunted lexicographers ever since, who have combed books of poetry and literature in an attempt to collect such a large number of relevant terms. Conveniently for pun-loving scholars of Arabic, the word maʻarrah is not only al-Maʻarrī’s hometown and the source of his name, but also a noun meaning “shame” or “disgrace,” and thus the poet’s challenge is known as maʻarrat al-Maʻarrī.

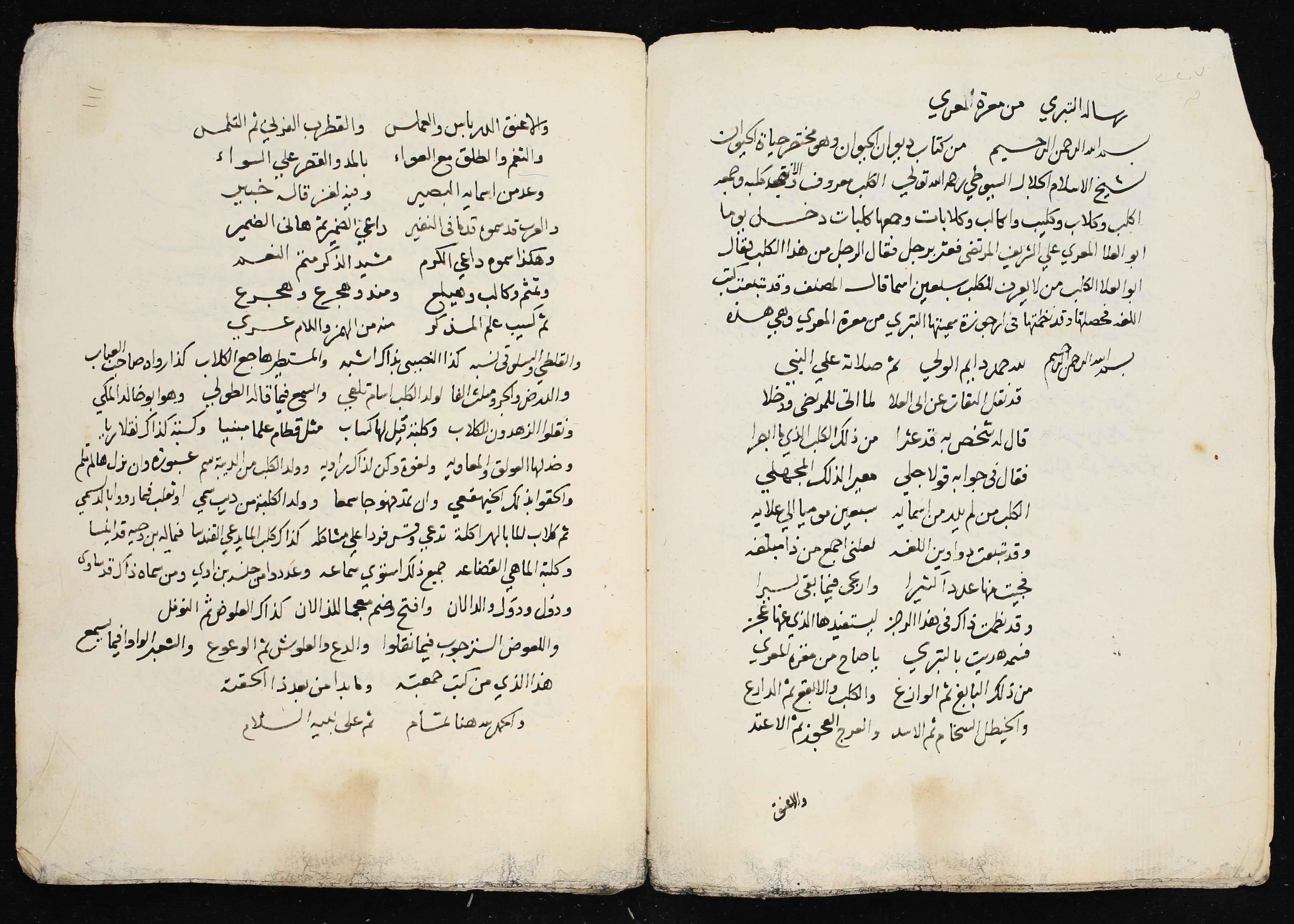

Although Ibn al-Khiyamī and others mention this anecdote, perhaps the most noteworthy attempt to pass al-Maʻarrī’s test was undertaken by Jalāl al-Dīn ʻAbd al-Raḥmān al-Suyūṭī (1445–1505 CE), an Egyptian scholar who wrote on almost every topic imaginable. The poem of al-Suyūṭī, in which he attempts to collect 70 Arabic names for dogs, is entitled al-Tabarrī min maʻarrat al-Maʻarrī, or “Clearing myself of the shame of al-Maʻarrī.” So far, the poem is found in one manuscript digitized by HMML, copied in 1586 CE and held at the Āl Budeiry library in Jerusalem: ABLJ 00752 045.

After describing the story of al-Maʻarrī’s confrontation, al-Suyūṭī lists the terms he has been able to identify, arranging them into poetic verse both as a further demonstration of skill and in order to make the text easier to memorize. Ultimately, even al-Suyūṭī falls several names short of al-Maʻarrī’s target, leaving us to wonder if anyone could truly meet the challenge. Perhaps this is yet another enigmatic way for al-Maʻarrī to remind tormented lexicographers of what Ibn al-Marzubān called the “superiority of dogs,” and the shortcomings of “those who wear clothes.”