Reversal Of Fates: Access Through Photographs Can Be A Counterbalance

Reversal of Fates: Access Through Photographs can be a Counterbalance

Cultural losses continue to beset communities around the world, especially in areas subject to armed conflict. The loss can manifest in multiple ways: destruction and damage, dispossession, the displacement of individuals, and other forms. But while the trauma these wider events inflict upon communities remains permanently scarring, sometimes aspects of the long-term impact upon a community’s treasured manuscripts can be mitigated.

Before the War

At the time of the 2003 Iraq invasion, the Chaldean Patriarchate of Baghdad, fearing the possible destruction of its manuscript collection, buried the archive in order to protect it. Often this action has been a recourse for communities under threat, including among Jews during the Holocaust and Armenians during the Armenian genocide.

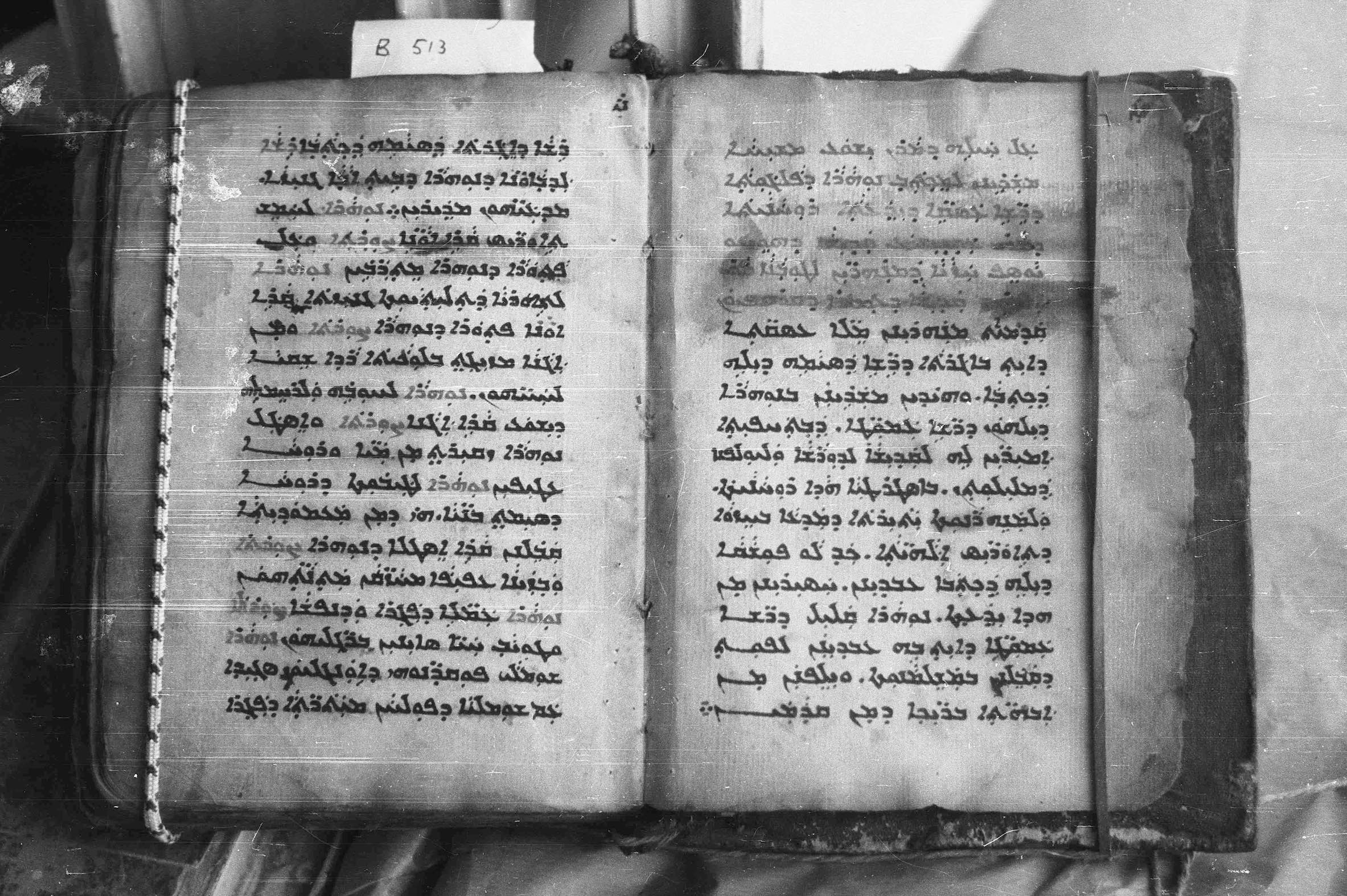

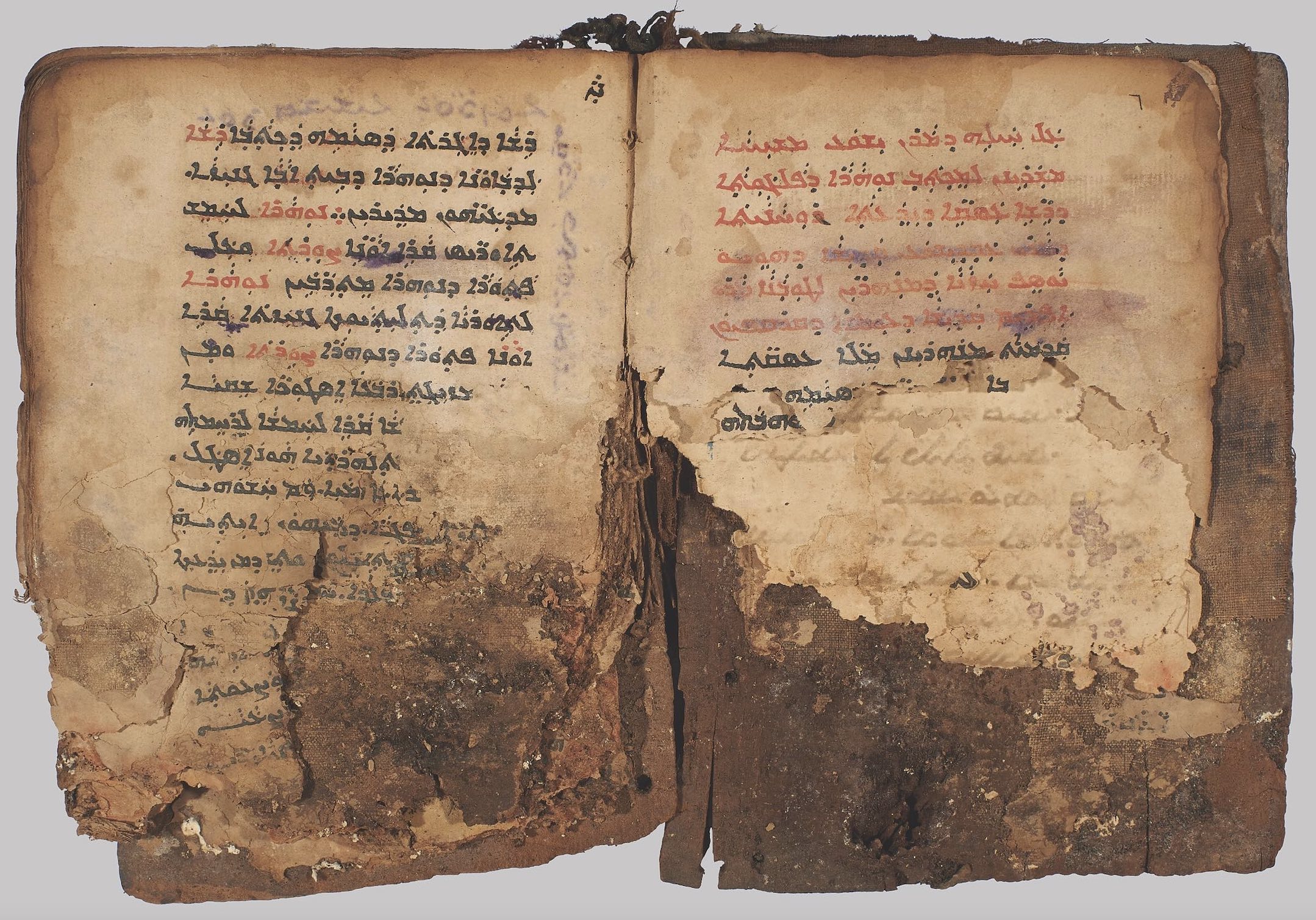

In Iraq, most of the collection survived. However, flooding from the Tigris River damaged some volumes to varying degrees. One of the most affected was a seventeenth-century codex (CPB 00463): the bottom half of its pages disintegrated in the ground. While multispectral imaging can be helpful in recovering text on waterlogged pages, the complete loss of the bottom sections renders such technology of no help.

The manuscript was digitized by the Centre Numérique des Manuscrits Orientaux (CNMO) in collaboration with HMML in 2016. Despite its sad condition at that time, its text paradoxically remains fully readable—in another form.

Estonian scholar Arthur Vööbus—who in 1940, and again in 1944, fled his homeland due to the Soviet Union’s occupation—is responsible for our continued access to these pages. After being imprisoned by the Nazis, he emigrated to Chicago and spent the second half of his life teaching and studying manuscripts. During the third quarter of the twentieth century, Vööbus photographed codex CPB 00463 and hundreds of other Syriac books throughout the Middle East, creating a valuable photographic archive now included among HMML’s collections. Although the current physical state of the book cannot be reversed, through these earlier images created by Vööbus, the ravages of time can be undone.

Record of Ownership

Images of manuscripts also help document the provenance of items that are taken from their rightful owners during war or under other circumstances. The images are evidence of histories, invaluable in situations where legally uncontestable ownership records do not exist or can be easily eradicated.

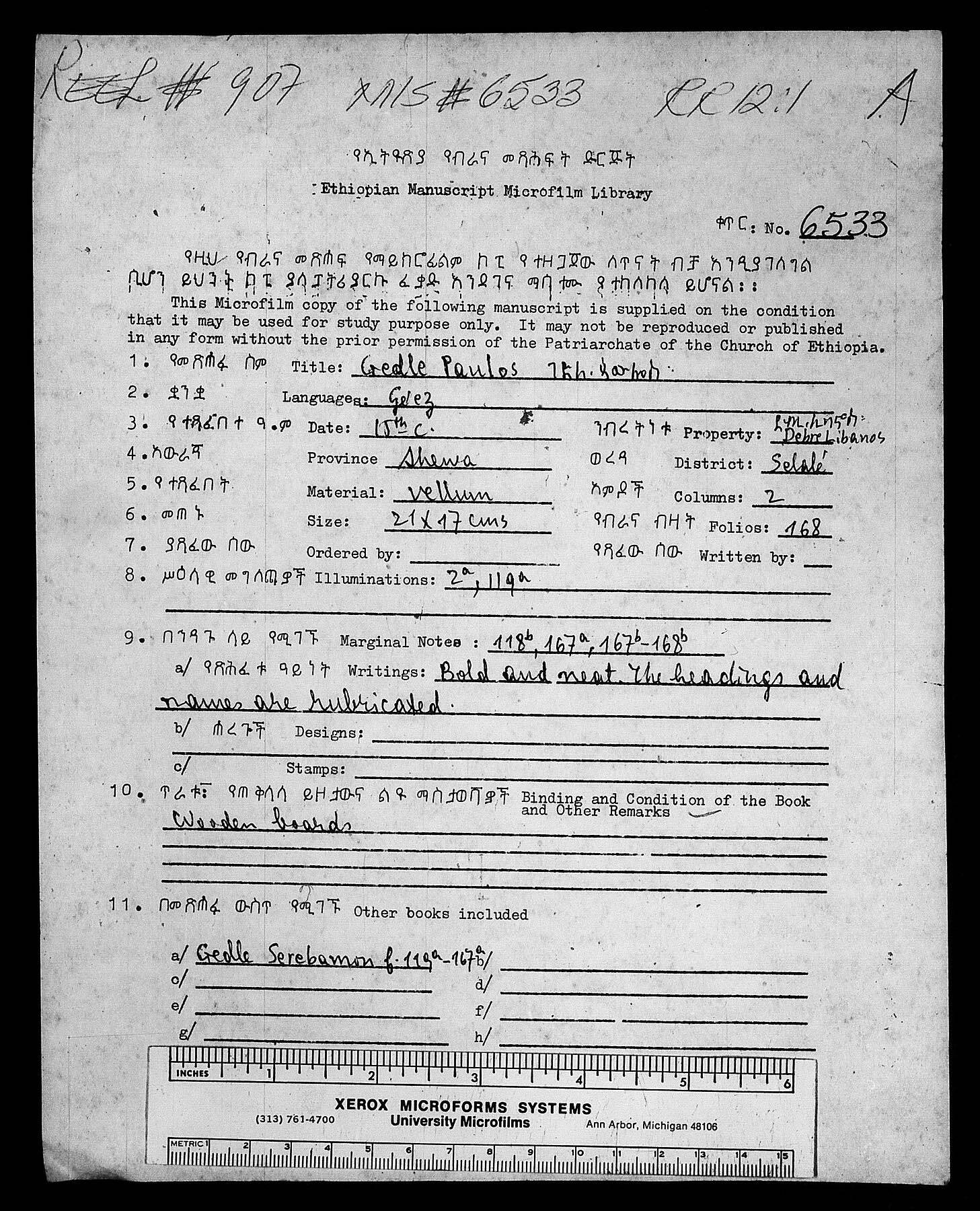

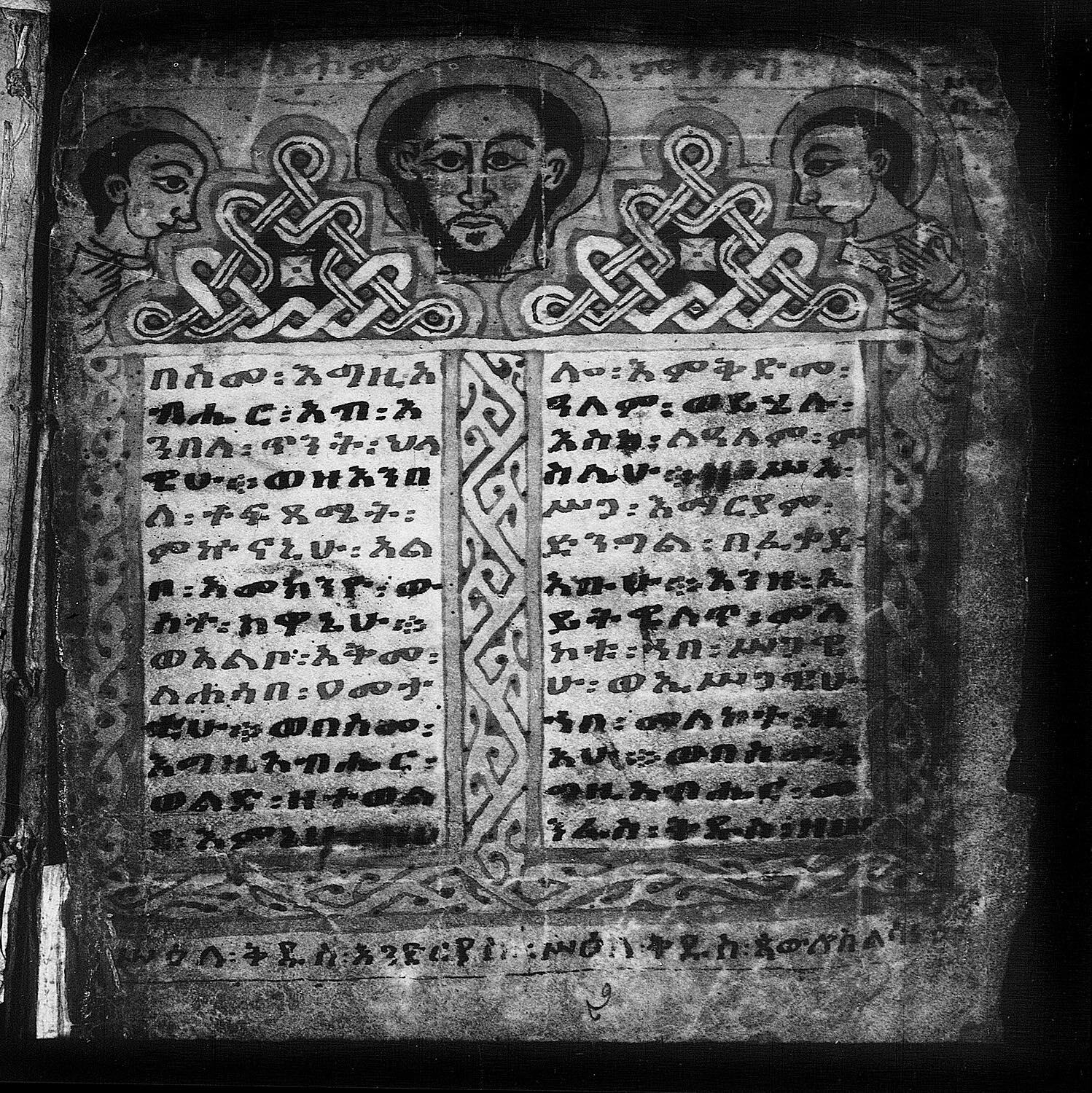

For example, while the Ethiopian Manuscript Microfilm Library (EMML) is the largest and most important repository for scholarly access to texts in Geʻez, it also records the ecclesiastical owners of individual items, an aspect for which it has only started to become more utilized.

A few years ago, the return of EMML 6533 to Dabra Libānos Monastery by Howard University was occasioned by the available public record of ownership created through the manuscript being microfilmed in Ethiopia in 1978. As is clear from the university’s simultaneous retention of dozens of other Ethiopic manuscripts donated alongside the repatriated volume, it was not a broader institutional policy that prompted the return of this cultural item to Ethiopia; it was the availability of its public record.

The images—attesting to the manuscript’s place in time—resulted in the monks’ dispossession being temporary, not permanent. This is unlikely to be the only such case, as HMML has identified a growing number of manuscripts that were microfilmed by the EMML in Ethiopia and are now held in Western collections.

As an EMML partner, HMML continues to inform pertinent stakeholders about such items. Ongoing digitization and cataloging work not only serves the interests of scholars and manuscript communities—it also creates crucial, publicly-accessible provenance records that provide an increasingly robust bulwark against manuscript theft and trafficking.

Access from Afar

Conflicts breed displacement. Sometimes this takes the form of physical possessions being moved from one place to another, but more often it results in people fleeing for their safety. Occasionally they can return to their former homes, but when circumstances do not permit this, people can become disjoined from major parts of their identities.

For many communities, such displacement has included loss of access to works of religious and cultural importance that stayed behind.

In some cases, handwritten books remain one of the closest links to a never-forgotten homeland, as they were for the late Professor Getatchew Haile, curator of the Ethiopia Study Center at HMML. Getatchew was fortunate that he could continue to read and remain connected to Ethiopian manuscripts in Minnesota, despite being unable to return to Ethiopia. And the world was fortunate that Getatchew made the EMML collection widely accessible, through cataloging thousands of manuscripts and promoting access in innumerable ways.

History can be lost through destruction, but history can also be made through a commitment to preserving and ensuring widespread public access to global handwritten heritage.

This story originally appeared in the Winter 2022 issue of HMML Magazine.