Migration, Digitization, And Preservation A Case Study Of A Somali Manuscript

Migration, Digitization, and Preservation - A Case Study of a Somali Manuscript

Heritage

The Nigerian literary giant Chinua Achebe once observed, “Well, it is not true that my history is only in my heart; it is indeed there, but it is also in that dusty road in my town, and in every villager, living and dead, who has ever walked on it. It is in my country too, in my continent and, yes, in the world. That dusty little road is my link to all the other destinations.”

For me, the question has always been tied to my ancestral heritage: who do I come from? How did they live? What did they care about? What shaped their world and how can their lives inform my own?

As part of my clan-family’s scholarly responsibilities, it was our ancestral duty to interpret sacred law, adjudicate, and settle disputes. Some of the ancestral titles in my family include “Aw,” “Ma’allim,” “Shaykh,” titles which reflect their role in Somali society. The most famous scholar in my lineage is Shaykh Muḥammad Muʾmin al-Laylkasī, the eponymous progenitor of my subclan. He left as an inheritance to his descendants a series of manuscripts that contained his living will and his commentaries on various classical Islamic texts.

Migration

On the eve of the Somali Civil War, tensions ran high in my ancestral home of Galdogob as different factions fought for control of the buffer city and the larger region. The then head of the Muḥammad Muʾmin clan (my clan family) left the country first for Kenya, then to the Emirates, all the while carrying a set of ancestral manuscripts in tow. There, his knowledge of Islam earned him the patronage of a local notable; he told the notable of his ordeal and, for the first time in history, the familial manuscripts were photographed and cataloged, kept in a private collection.

Eventually the notable passed away and his patronage ended. The most important manuscript was poorly kept, and entire folios fell into disarray as it was neglected. In the early 2000s, my uncle, the noted linguist and oral historian Abdi Mohamud Suleiman, was living in the Emirates and made every attempt to preserve the manuscript. What we have of the manuscript today is due to these efforts and diligence to preserve this heritage.

Preservation

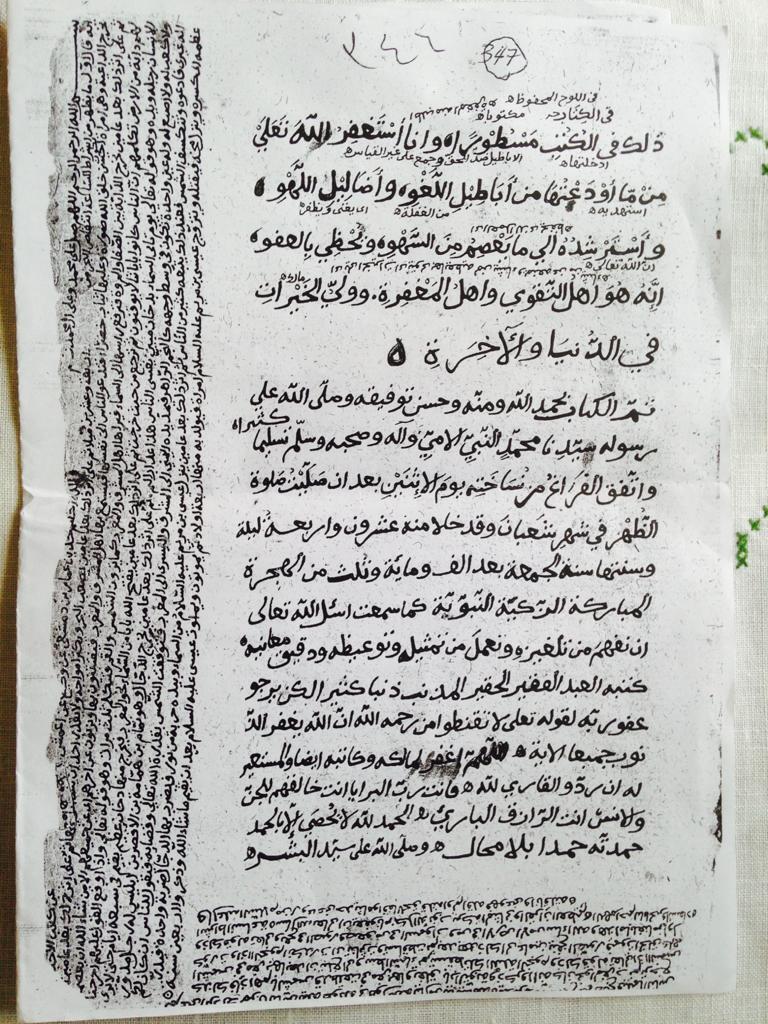

I first became aware of this manuscript in 2011 at a family meeting discussing which family should now take hold of what remained of it. I completely forgot about it for nearly a decade. In October 2020, my uncle, Abdi Mohamud Suleiman, reached out and asked if I would be willing to help and analyze and assess the contents of the manuscript, and naturally I jumped at the opportunity. In January 2021, I began my fellowship at HMML, and my training in database management and manuscript analysis aided me greatly in making sense of this ancient document. In February 2021, I began experimenting with AI image enhancement software and the manuscript began to reveal its secrets in earnest.

The Manuscript

Our research shows that what we have of the manuscript is a rich, language-based commentary on parts of the Maqāmāt (Assemblies) of al-Ḥarīrī. The manuscript also contains his literary feat al-Risālah al-Sīnīyah (The Treatise of Letter Sīn), a text in which every word has the Arabic letter sīn in it.

The towering figure of al-Qāsim ibn ʻAlī al-Ḥarīrī (1054–1122), the inimitable Basran master of prose, looms large in the world of Islamicate belles-lettres nearly a millennium after his death. Over the course of Islamicate intellectual history, many commentaries have been written on al-Ḥarīrī’s work, and Somali scholars were no exception to the trend. In the commentary found in the manuscript, the scholar al-Laylkasī shows an excellent command of the principles of grammar as well as morphology, commenting on the origins of rare words and providing etymologies where necessary. His is an exercise in simplification, making the words of the master al-Harīrī accessible to even a novice reader.

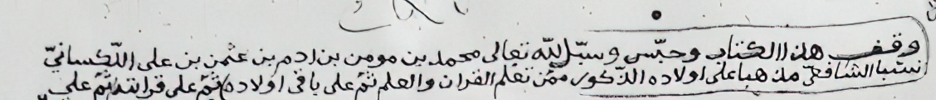

Two areas of significance in this manuscript are the waqf (endowment notice) and the colophon, which act as identifiers for the manuscript, highlighting its authorship, chronology, and intellectual significance.

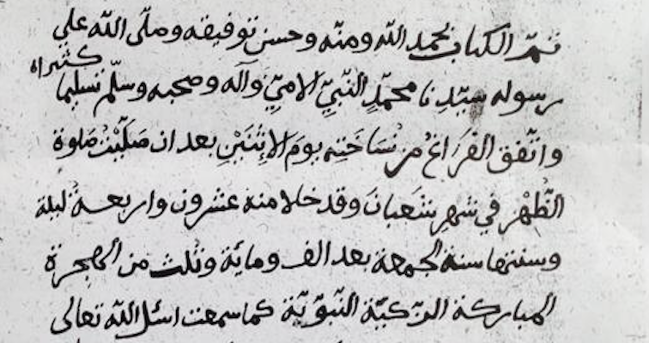

The waqf:

“This book is endowed by Muḥammad ibn Muʾmin ibn Ādam ibn ʿUthmān ibn Ali al-Laylkasī al-Shāfiʿī, to my male descendants who learn the Qur’an and then to the rest… of the family and the scholars of the Muslim Ummah.”

This highlights the hereditary nature of this scholarly endeavor. The desire to preserve and maintain the tradition was paramount to the clan’s shaykh, Muḥammad Muʾmin, and is an observable trend in other scholarly Somali clan-families.

An excerpt from the colophon:

“…completed on Monday, 24th of Shaʻbān after Duhur (noon prayer), 1103 AH/May 12, 1692.”

The colophon in this manuscript does three things:

- It establishes a concrete chronology to a previously “semi-mythical” progenitor.

- It provides a genealogical starting point that will help to corroborate other contours and accounts of the life of this scholar and his descendants, many of whom were active in the propagation of Islam across Somalia.

- It makes the author of the manuscript’s positionality clear via his alqāb (agnomen, cognomen) Muḥammad ibn Muʾmin ibn Ādam ibn ʿUthmān ibn ʻAlī al-Laylkasī al-Shāfiʿī, revealing that central to his identity was both his standing as a member of the Laylkase but also his membership in the Shafiʽi school of law. The interplay between these two identities could well reveal a wealth of previously understudied scholarship.

I believe that as we continue to preserve and research the Islamic manuscripts and material heritage of Somalia, we will tap into an oft-neglected subset of the field of Islamic Studies, one that certainly deserves its day in the sun.