Creating Cataloging Standards For Regional Names

Creating Cataloging Standards for Regional Names

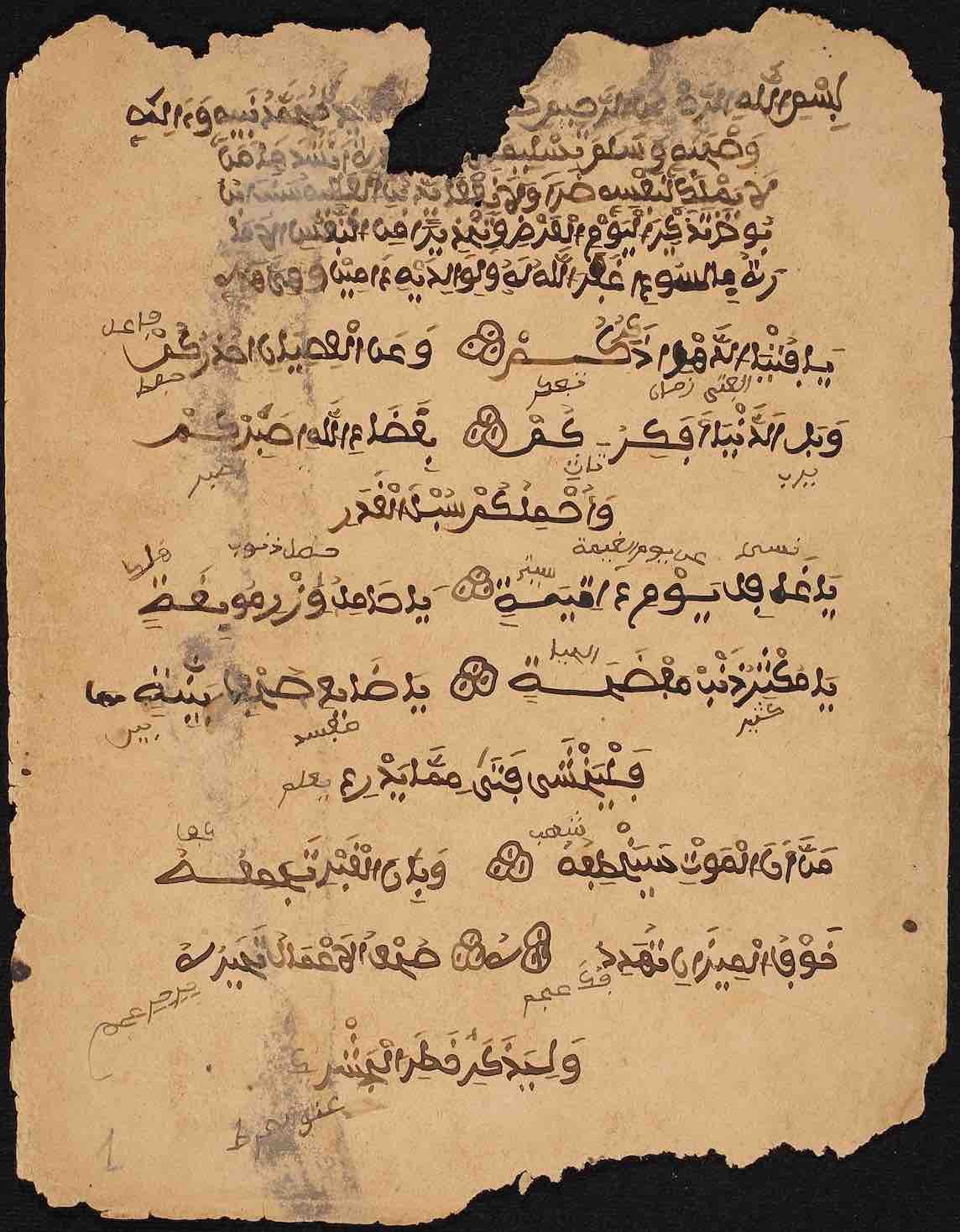

Timbuktu’s SAVAMA collections contain thousands of authors from various regions of the Muslim world. Most authors are ‘household names’ in the classical system of Islamic learning (established many hundreds of years ago) and as such are also found across HMML’s other Islamic collections. However, a significant minority of these authors are not known outside of West Africa or indeed outside of their local areas. Their names are usually not established in manuscript catalogs and as such, their contributions to world knowledge remain unknown.

At HMML we’re celebrating the addition of the first of these local scholars, Yeɗi Sanba Ɓooyi, to Reading Room. Yeɗi belonged to the Fulani people, one of West Africa’s many ethnic groups, which include Bambara, Hausa, Soninke, Songhai, Tuareg and many others.

Understanding a Name

In the form of Yeɗi Sanba Ɓooyi’s name we have something extraordinary: the three parts of the name all have a clear meaning in the Fulfulde language, the primary language of the Fulani people. Yeɗi means “gift,” Sanba is a term given to the second son and Ɓooyi means the child (a boy or a girl) who was born many years after marriage. The first name is that of the author himself, the second name is that of his father and the third that of his grandfather.

These three names demonstrate the diversity and great specificity of Fulani naming systems. In the absence of a tradition of 'family names' in Fulani culture, this patrilineal naming system served to precisely identify individuals, though before the 19th century it was common to use matrilineal names also. In contrast, the Arabic naming tradition requires “Ibn” (son of), of which there is no universally used equivalent in Fulani, to clearly show patrilineal descent.

Arabic names also require a nisbah (akin to a 'family name') after the patronymic. For this reason, Fulani authors are typically given the nisbah “al-Fulani” or the place in which they lived or were active (for example al-Tinbuktī or al-Māsinī) when, again, this was not necessary in Fulfulde naming traditions.

As Arabic speakers and devout Muslims, many Fulani authors adopted these Arabic naming traditions in parallel with how they were known in their native Fulfulde.

Standardizing a Name

To replicate this dual identity in our cataloging work we created two names for this author, one following the Arabic convention (Yedi ibn Sanba ibn Būḍ al-Fulānī يد بن الفقيه سنب بن بوض الفلاني) and the other following the naming and modern orthographic conventions for the Fulfulde language (Yeɗi Sanba Ɓooyi).

As part of a three-year grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH), HMML is now a contributor to both the Library of Congress (LC) and, through their submissions, the Virtual International Authority File (VIAF). Through this process, the names that HMML standardizes are now the international standard. Libraries and archives around the world can link material related to a person, such as “Fulānī, Yedi ibn Sanba ibn Būḍ,” by using this name.

This work serves to enrich international databases with authors from historically underrepresented groups, while preserving the way these individuals are known and would be searched for in their native cultures.