A Decade In Mali

A Decade in Mali

It began with a dinner in 2013. A HMML board member found himself seated next to Deborah Stolk, then a program director with the Prince Claus Fund (PCF) in Amsterdam. He told Deborah about HMML, and she mentioned that PCF had helped fund the evacuation of manuscripts from Timbuktu.

We had all read about the occupation of Timbuktu by a coalition of armed groups in April 2012 and had seen photos of burning manuscripts. After the retaking of the city by French paratroopers in January 2013, it emerged that almost all of Timbuktu’s libraries had been relocated to Bamako, Mali’s capital, in advance of the occupation. As a result, relatively few manuscripts were found and destroyed.

I had a trip to Ethiopia in the works and arranged to meet Deborah at Schiphol Airport in Amsterdam on my way home. She showed me photos of the 1,400 metal boxes—containing manuscripts from more than 30 family libraries—being transported by boat and truck to Bamako. I shared photos from HMML’s recent projects and suggested that we might be able to help with digitization and online access. The result was an email introduction to Dr. Abdel Kader Haidara, a member of a prominent Timbuktu family and organizer of the rescue operation.

By August 2013, I was in Bamako with Walid Mourad (longtime HMML field director) to meet Dr. Haidara and his team at SAVAMA-DCI (Sauvegarde et Valorisation des Manuscrits et Défense de la Culture Islamique), a Malian NGO and cooperative of private library owners in Timbuktu, founded by Dr. Haidara in 1996.

Most of the evacuated manuscripts were still in metal boxes, stashed in apartments throughout Bamako. The move of the manuscripts from the desert climate of Timbuktu to the humidity of the capital posed a conservation challenge, compounded by the boxes being tightly packed without air circulation. Several international partners were helping with the rental of storage locations and the new SAVAMA-DCI headquarters, as well as with conservation and inventory of the contents of the boxes, but no one yet had come forward to support digitization. That would be HMML’s contribution.

At the start of 2014, two HMML digitization studios were up and running in Bamako, and during the next few years the project grew to six studios, thanks in part to forward-thinking grants from Arcadia Fund in 2011 and 2015. The Juma Al-Majid Center for Culture and Heritage in Dubai, United Arab Emirates, contributed six more studios, managed by HMML after their first year of operation. As other partners fell away, Hamburg University emerged as the lead for conservation and inventories, with funding from the Gerda Henkel Stiftung and the German Foreign Ministry. In total, more than 292,000 manuscripts would be digitized in HMML’s Bamako studios.

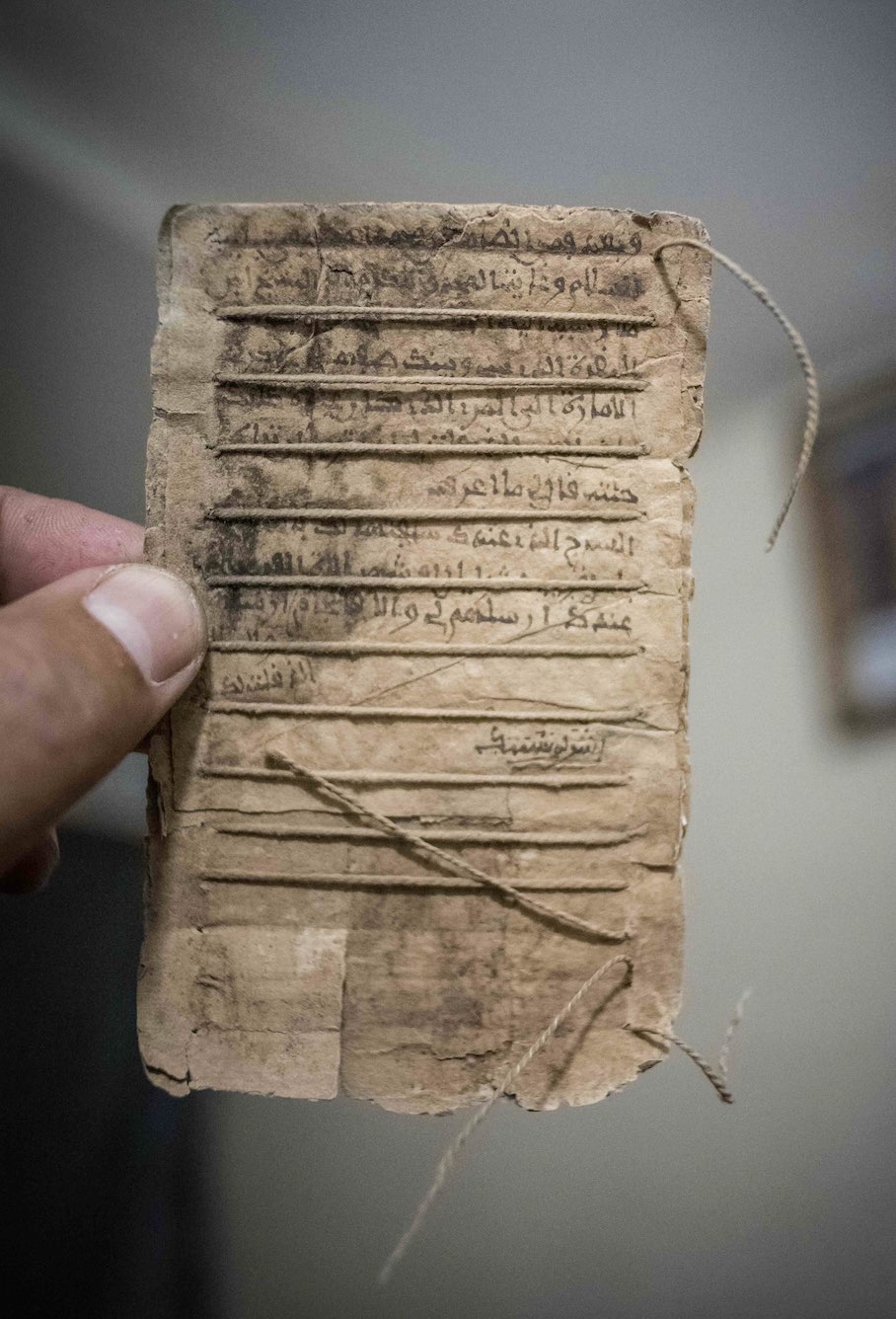

Soon we learned that in Timbuktu some manuscripts had survived—safely hidden at the three major mosques—and HMML began a partnership with Sophie Sarin, a Swedish resident of Mali. She had recently met with families whose manuscripts remained in Timbuktu. They agreed to a digitization project, funded initially by the British Library’s Endangered Archives Programme (EAP) then carried forward by HMML. Our three-year project in occupied Timbuktu, beset by logistical challenges, resulted in an additional 7,279 manuscripts digitized.

And then there was Djenné. The industrious Sarin had helped establish a community-based manuscript center next to the Great Mosque to provide a safe home for private collections. I had visited the site in 2013 and observed their digitization efforts, then funded by the EAP. When that grant ended in 2019, HMML kept the work going, photographing 2,567 manuscripts from more than 200 repositories.

HMML’s digitization work in Mali is now complete, resulting in an estimated 4.25 million unique image files representing 302,000 manuscripts. Our work of cataloging these manuscripts for online access is underway and will continue for years.

Taken together, the projects in Bamako, Timbuktu, and Djenné were HMML’s largest-ever investment in manuscript photography. The launch of HMML’s online Reading Room (vhmml.org) in 2015 was well positioned to receive the massive flow of images. Today, 130,000 manuscripts can be viewed in Reading Room—nearly 25,000 of these from Mali alone.

Over the course of a decade, the projects in Mali transformed HMML’s collections from primarily European and Eastern Christian manuscripts to include the largest single online source of digitized Islamic manuscripts in the world. These materials, in turn, have supported new research, partnerships, and tools. Users of international databases—receiving catalog information from HMML Authority File—are benefiting from the identification of authors and texts from groups historically underrepresented in such systems. HMML is now digitizing Islamic collections in Mauritania, India, and Pakistan, in part thanks to our success in Mali. And around the world, people are connecting for the first time to images that give a dynamic view into the handwritten heritage of West Africa.

A version of this story originally appeared in the Summer 2024 issue of HMML Magazine.