Rebirth, Reform, And Revision

Rebirth, Reform, and Revision

Reading the Bible during the Reformation — Part 2

In Part I of Rebirth, Reform, and Revision, we introduced late medieval approaches to reading the Bible and the received tradition for understanding Biblical history. As we saw, the innovation of printing in the 15th century at first continued many of these approaches, but at the same time, printing supported the development of new modes of reading the Bible. Starting with Martin Luther’s call for reform, we now turn to the further advance of new approaches to reading, translating, and studying the Bible in the 16th and 17th centuries. Translations into many European vernacular languages appeared, alongside massive polyglot editions with the Biblical text in various early transmissions of the text. Even in England, where translating the Bible into English was long banned, new translations appeared, and by 1540 English had become the “authorized” language for the Bible. Even the Catholic Church supported the resurgence of Biblical studies through reform of the Latin (Vulgate) version, translation into English (Douay and Rheims editions), and the production of Biblical texts in Syriac and Arabic. Finally, we witness the efforts to promote understanding of the Bible through printed imagery in woodcut illustrations and engravings.

Martin Luther (1483–1546)

Born in Eisleben, Saxony, in 1483, Martin Luther was destined for the legal profession, a practical vocation for the son of an ambitious businessman. Instead, Luther underwent a terrifying experience that prompted him to dedicate his life to God. He joined the Augustinian order and studied theology, receiving the Doctor of Theology in 1512, whereupon he was received into the faculty at the University of Wittenberg. While it is not possible here to delineate his entire career, his work 500 years ago set into motion the developments we trace in this exhibit and forever changed the way Christians approach and study the Bible.

A Theological Ignition Point

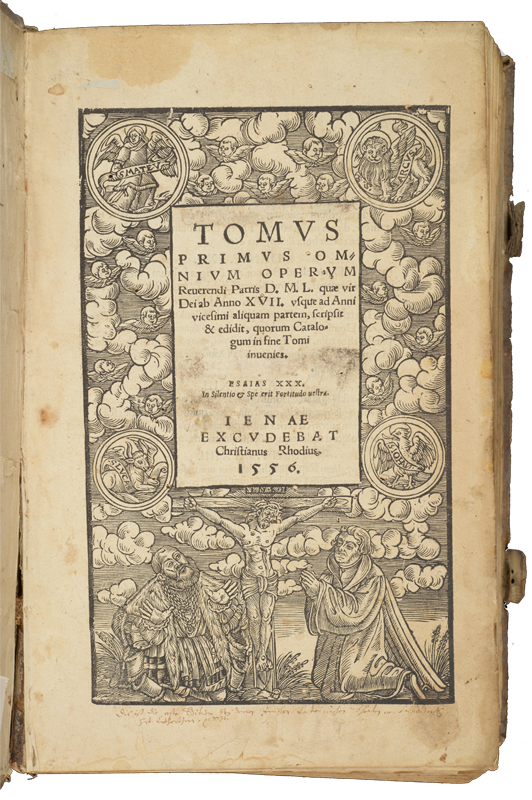

Luther’s Disputatio pro declaratione virtutis indulgentiarum (the “95 Theses”)

On October 31, 1517, a theology professor at the recently-founded University of Wittenberg called for an academic disputation on the Catholic Church’s practice of selling indulgences. Martin Luther’s 95 Theses were quickly embraced by many disaffected Catholics throughout Germany. Over the next few years, these were reprinted, translated into the vernacular, and widely disseminated—even beyond the German-speaking world. The earliest copy in the Saint John’s collections dates from 1556, a decade after Luther’s death.

Becoming a Part of the Story

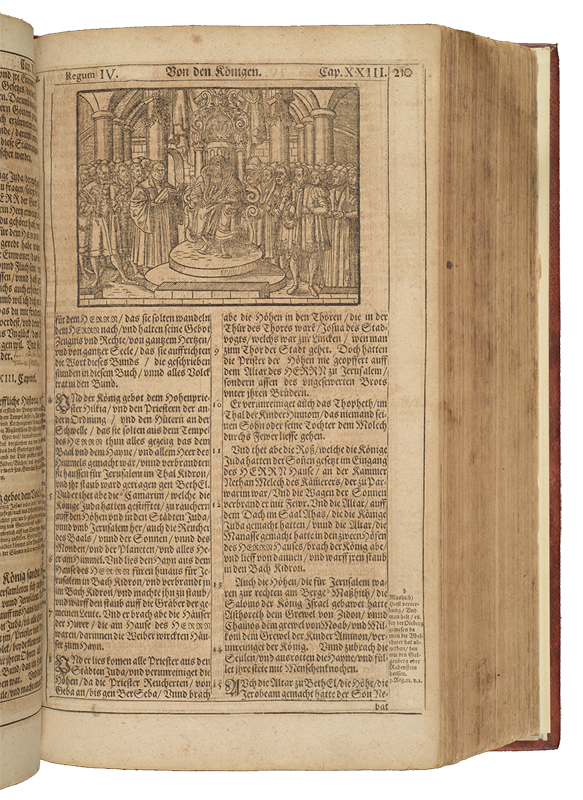

Luther Reading to a Political Leader (the Elector Frederick the Wise?)

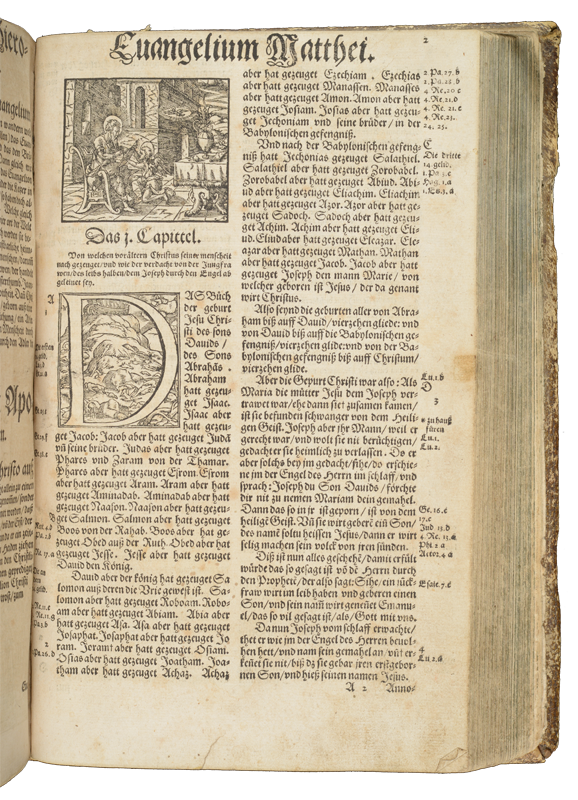

While hiding from imperial authorities in 1521-1522, Luther used Erasmus’ Latin-Greek edition to translate the New Testament into colloquial German and published this translation in late 1522. While his complete translation appeared in 1534, the earliest edition in the Saint John’s collections is much later, from 1626. The many woodcuts with contemporary representations make this an especially interesting version. At the end of 2 Kings we find Martin Luther reading to a political figure—possibly his protector, the Electoral Prince Frederick the Wise.

The Vernacular Bible in Everyday Life

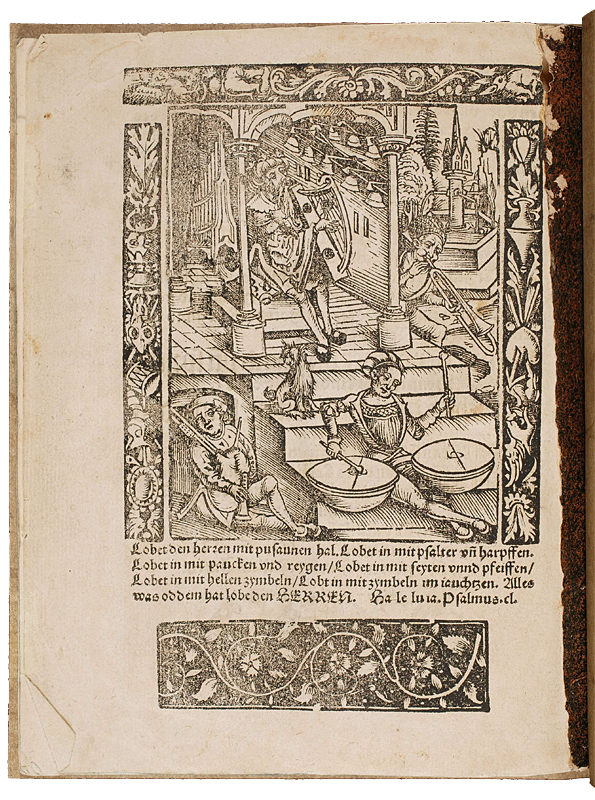

A Reforming Pamphlet with Hymns from Strasbourg

Luther’s attacks on indulgences and on other practices of the Catholic Church came in an historical context of church reforms going back over a century, and it found immediate resonance across the German-speaking areas. Already in 1525, Martin Bucer (1491-1551) was introducing liturgical reforms in Strasbourg. This pamphlet outlines changes in the Mass, baptism and the consecration of marriage. It closes with a depiction of King David with his musicians and the admonition from Psalm 150 that all that has breath should praise the Lord.

Building a Community of Biblical Study

Luther’s Teachings at Table

After Luther’s death in 1546, his followers collected their notes from the frequent discussions around his table. These were published as colloquia or “table-talks” and were arranged by subject area. The first chapter of the 1569 edition is on “God’s Word, or the Holy Scripture,” in which Luther describes the Bible as a large forest in which there are all manner of trees, from which one could pick many kinds of fruit—consolation, teaching, instruction, admonition, warning, etc. Luther’s use of such simple, earthy descriptions became one of his trademarks.

A Multitude of Languages

Across Europe the 16th century produced a blossoming of translation activity, with the Bible being printed in most European languages, including English, French, German, Italian, Spanish, Dutch, Slavonic, etc. At the same time, intense study of the sources was underway to find the most accurate copies and to work toward the purest form of the text. The Reformers turned away from the received translations of the Middle Ages—often based on Latin or mixed with non-Biblical materials—and endeavored to work from the earliest languages of the Bible, primarily Greek, Hebrew and Aramaic. Catholics responded with their own translations into several languages

Printed In the Language of the People, but in a Different Country

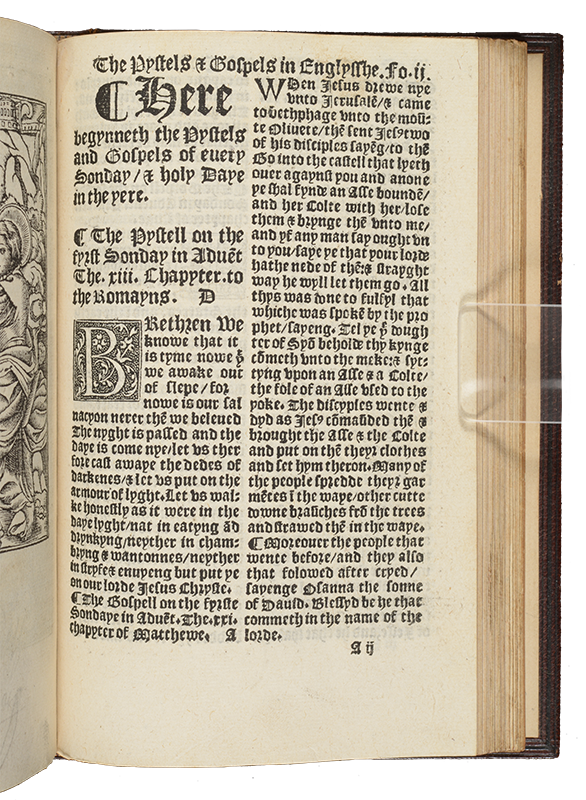

Early English Translations from the New Testament

When Henry VIII became king of England, the translation of the Bible into English was still forbidden and punishable by death. Translators like John Wycliffe and William Tyndale paid for their Bible translations with their lives. Yet in the mid 1530s, Henry reversed course and banned Latin Bibles and only allowed Bibles in English. Analagous to a Book of Hours, this Primer offers selections from the Gospels and Psalms for private devotion, while the latter part of the book offers readings from the Epistles and Gospels arranged according to the liturgical year.

The Scholar Printers

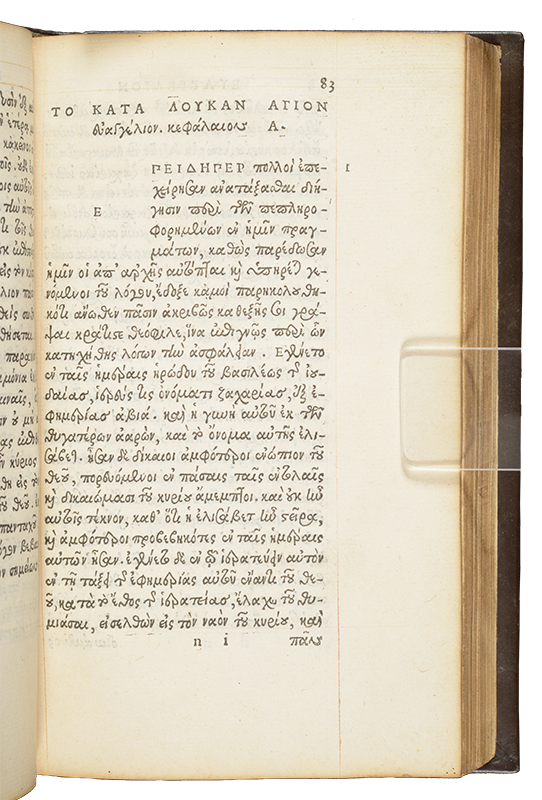

A 1534 New Testament in Greek

In the early 16th century, printers and publishers across Europe dedicated their work to providing the most accurate editions possible. Many scholar printers lived in Paris—including the Estienne family and Simon de Colines (1480-1546). This was the first, albeit flawed, Greek edition printed in France. Later, Robert Estienne published Greek New Testaments that set the standard for many decades. Sadly, the actual printer of this edition, Antoine Augerau (1485-1534), was condemned as a heretic and executed a few days after its publication.

In Print for the First Time

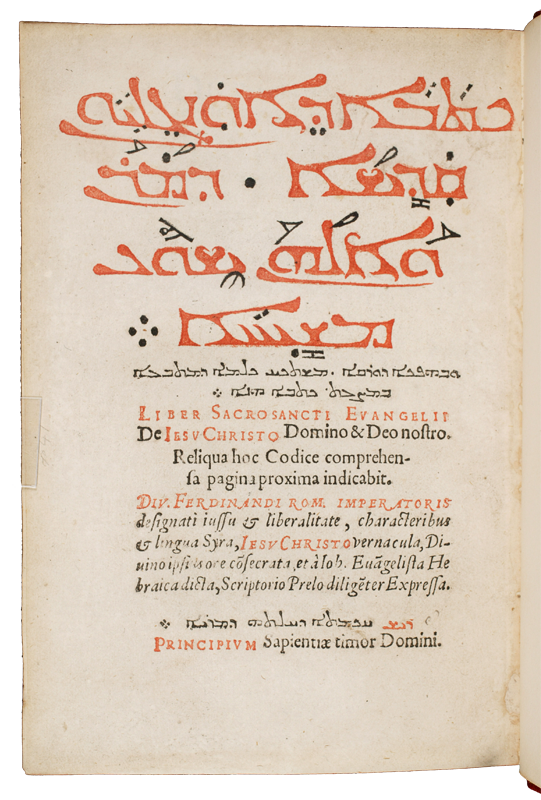

The New Testament in Syriac

At the same time that the Protestants were expanding their European influence through vernacular Bibles, the Catholics were also looking to expand their own influence. A golden opportunity arose when the Syriac Patriarch sent his envoy, Moses of Mardin, to Rome in the 1550s. One result of this contact from the East was the publication in 1555 of the first edition of the New Testament in Syriac—sponsored by the German Emperor, Ferdinand I. It was intended for use by those Eastern Christian communities that were in communion with Rome.

The Work of a Former Benedictine

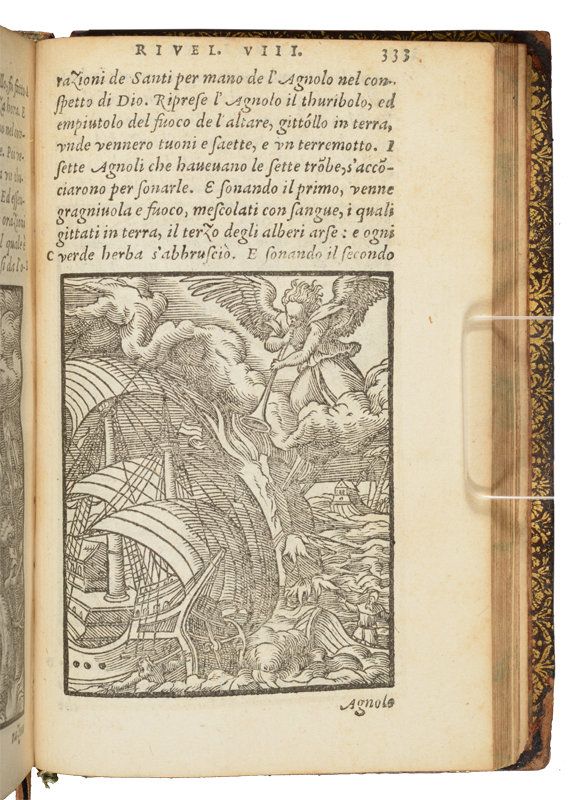

The New Testament in Italian

Jean Calvin’s followers in Geneva took Luther’s popularization of the Bible to heart, publishing new vernacular editions, including French, English, Spanish, and Italian. The translator of this edition was a former Benedictine from Monte Cassino, Massimo Teofilo (1509-1587?), who converted to Protestantism. Teofilo’s translation was later combined with a different translator’s version of the Old Testament to form the first complete Italian Bible edition in 1562.

The First Book in the Saint John’s Collections

German Catholic Bible (1572)

In 1534, a German Dominican named Johann Dietenberger, published a complete Bible in German translation for Catholics. His work is less a translation than a compilation and revision of different versions, including those of Martin Luther and Leo Juda (from the Swiss Reformed Church). While Dietenberger’s version gained some support in the 16th and 17th centuries, it fell out of favor over time and was superseded by other Catholic versions. This copy from 1572 was recorded in 1875 as the first book in the Saint John’s Abbey Library.

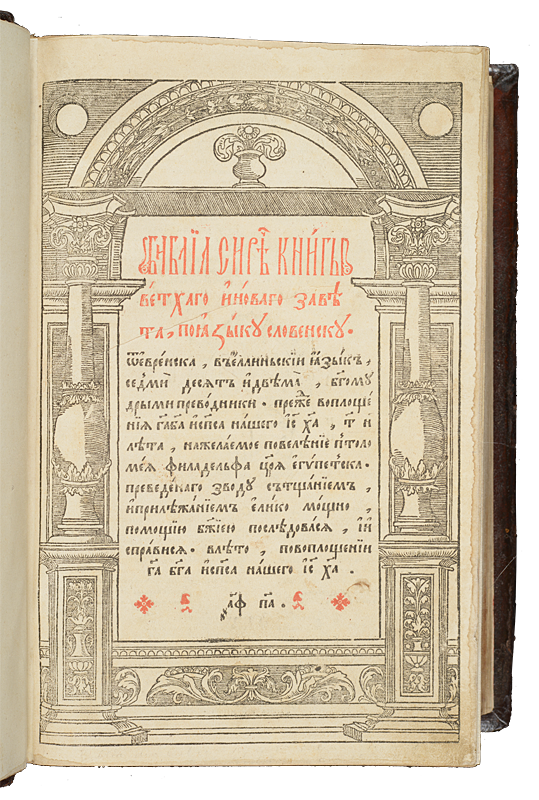

The First Complete Bible Printed in Slavonic

Ostrog Bible (1581)

While Slavonic translations of the Bible extend back to the 9th century, the earliest passages were printed in the 1490s and the early 16th century—primarily from the Psalms and Gospels. Prince Konstanty Wasyl Ostrogski (1526-1608) sponsored the publication of this first complete translation (based on the Gennadius version) as a means to support the Orthodox faith against inroads from Catholicism and to promote Ukrainian culture. Of the 1500 to 2000 copies printed, only about 300 are believed to be extant today.

Geneva as a Center for Biblical Research

Dissatisfaction with the Roman Church was deep in Switzerland, where Luther’s defiance quickly inflamed existing anger, producing a more extreme approach to reform, in particular through Huldrych Zwingli (1484-1531) and his followers. The leading city of French Switzerland, Geneva, was slow to embrace the Reformation at first, even expelling John Calvin in 1538, only to call him back a few years later. Under Calvin’s leadership, Geneva became a center for Biblical studies with connections across Europe. His presence and the relative freedom for intellectual curiosity in Geneva attracted other Biblical scholars, such as Théodore de Bèze and Robert Estienne (“Stephanus”), whose innovative work transformed our approach to the Bible. While still in Paris, Estienne published the first critical edition of the Greek New Testament (1550), and shortly after arriving in Geneva as a refugee he published the first Greek New Testament to use verse numbers (1551)—both practices that are still vital to Biblical studies today.

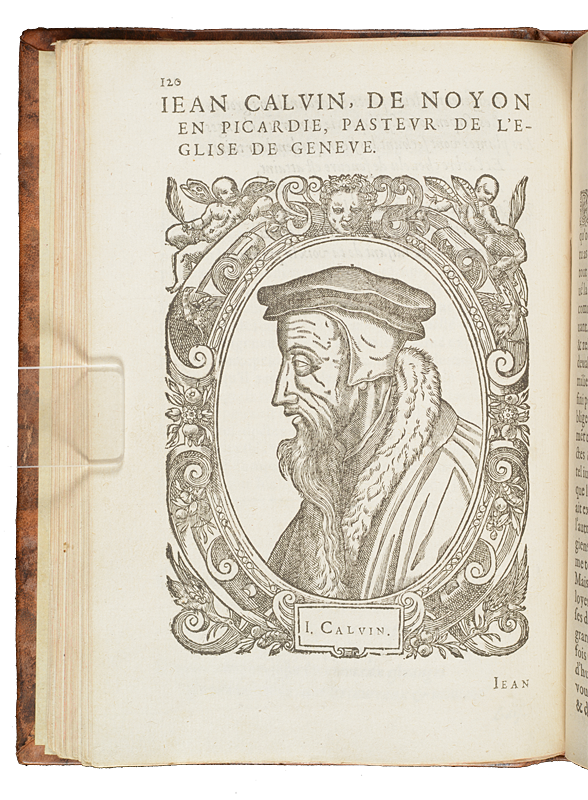

Leaders of the Reformation from the Geneva Perspective

True Portraits of the Great Reformers (1581)

By the 1580s, several reform movements across Europe were becoming established and were developing a sense of their own history. This book’s editor, Théodore de Bèze, was a Biblical scholar and close adherent of Jean Calvin, the leader of the reform movement in Geneva, Switzerland. He likely knew personally many of the Reformers depicted. Under Calvin’s and Bèze’s guidance, Geneva became a center for Biblical translation and scholarship, producing translations and editions in several European languages.

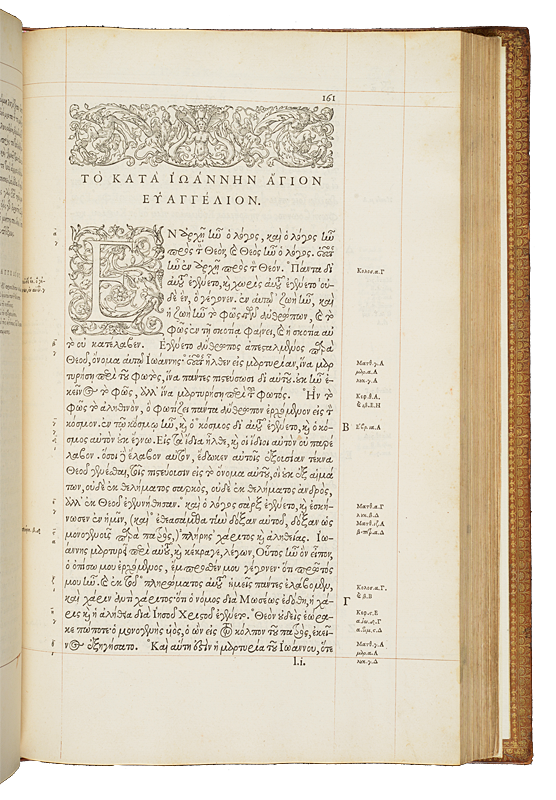

The First Critical Edition in Greek – A Royal Edition

Robert Estienne’s Third Edition of the New Testament (1550)

Robert Estienne (or Stephanus; 1503-1559) was the leading scholar printer in Paris in the 1540s, whose Greek New Testament editions (with type designed by Claude Garamond) set the standard for his time. The third edition (called the Editio Regia, 1550) was the first Greek Bible to have a critical apparatus, with references to 15 sources showing variants in the transmission. Opposition to this edition forced Estienne to flee Paris and re-settle in Geneva, where he produced one more Greek edition—with verse numbers added.

Catholic Response: Translations and Condemnations

Even as it opposed this new generation of Reformers, the Catholic Church was also promoting translation of the Bible into the vernacular. Catholic Bibles were published in the 16th century, for example, in English, French, and German. The Catholics often produced texts quite similar to those produced by the Reformers, even though they usually asserted Jerome’s Latin Vulgate as their source.

The Catholic world was also supporting the study of the source texts through projects like the Complutensian Polyglot Bible (published in Madrid, Spain, 1514-1517) and the Antwerp or Plantin Polyglot Bible (published in 1569-1573), which was prepared for Philip II, the Catholic king of Spain. The Vatican also sought new relations with Eastern Christian churches, which led to translations into non-European languages. Finally, in the late 16th century the Catholic Church undertook the revision of the received Latin Vulgate text, which became the standard Latin text for Catholics for the next four centuries.

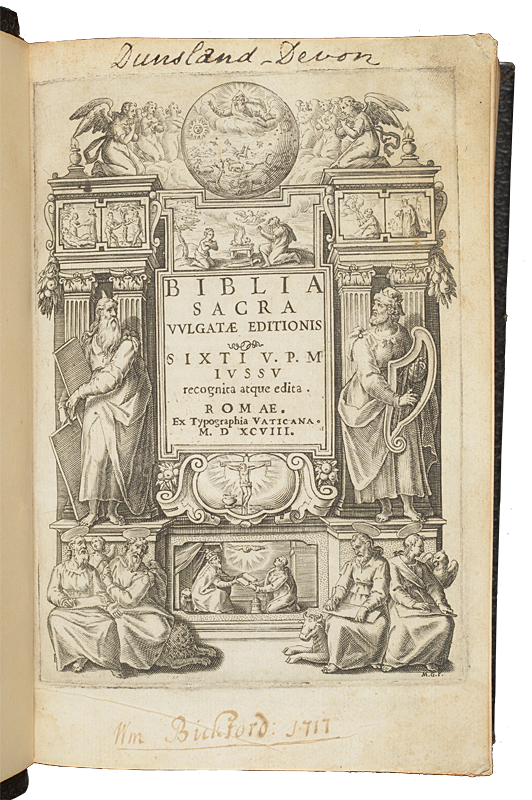

Revising the Vulgate

Sixto-Clementine Bible (1598)

A frequent charge by reformers against Catholic Bibles was the faulty transmission of Jerome’s Vulgate (Latin) version. Indeed, although the Vulgate Bible had been published frequently since Gutenberg, there was still no definitive edition by the middle of the 16th century. The Catholic Church response was to correct and revise the Vulgate, resulting in this edition prepared under popes Sixtus V (1585-1590) and Clement VIII (1592-1605). This was to become the official Latin Bible for Catholics until the late 20th century.

Reaching Out to New Communities

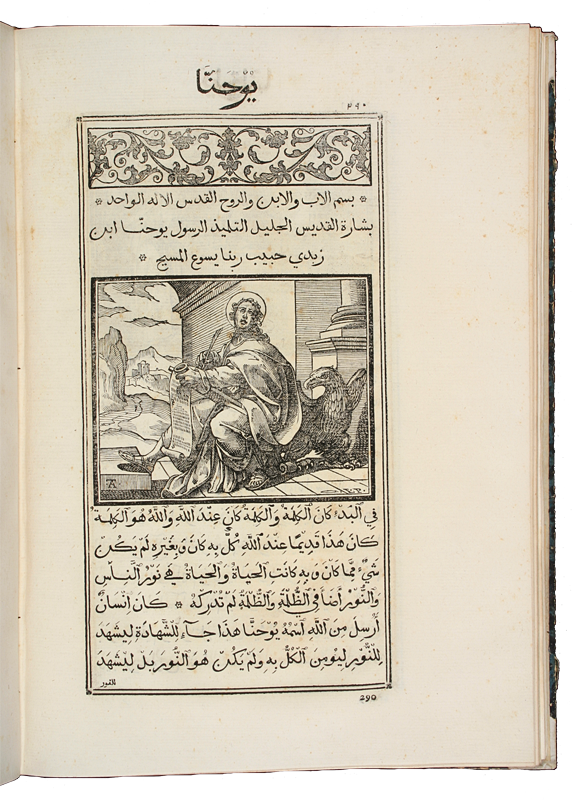

The Arabic Gospels (1591)

The 16th century not only witnessed the division of Western European Christianity, it also saw the opening up of relations with Christian communities in the Middle East, Africa, and South Asia. Already in 1513, a German produced the first printed Ethiopic Psalter in Rome and in 1555 the first complete New Testament in Syriac was published in Vienna. The Medici Press produced two versions of the Gospels in Arabic, featuring woodcuts by Antonio Tempesta (1555-1630) and type designed by Robert Granjon (1513-1589).

Polyglot Bibles

In the 15th century there was a great move toward studying materials in their original languages and not through Latin translations. Interest in the Biblical languages rose sharply, with renewed studies of Greek and Hebrew, as well as other Semitic languages. Polyglot (or “multilingual”) Bibles reproduce the text in multiple languages across parallel columns for easy comparison of different textual transmissions. Already in 1516, the first printed polyglot edition of the Psalms was published in Genoa, Italy, and was soon followed by Erasmus’ Greek New Testament.

Today Erasmus’ edition is criticized for errors introduced by the rush to get published before the Complutensian Bible. This new approach to studying the text, which brings together different avenues of Biblical transmission to establish variants, reached its logical climax a century and a half later in the London Polyglot, which parallels more languages (including Arabic, Persian and Ethiopic) than any of the others

The Bible in Multiple Tongues

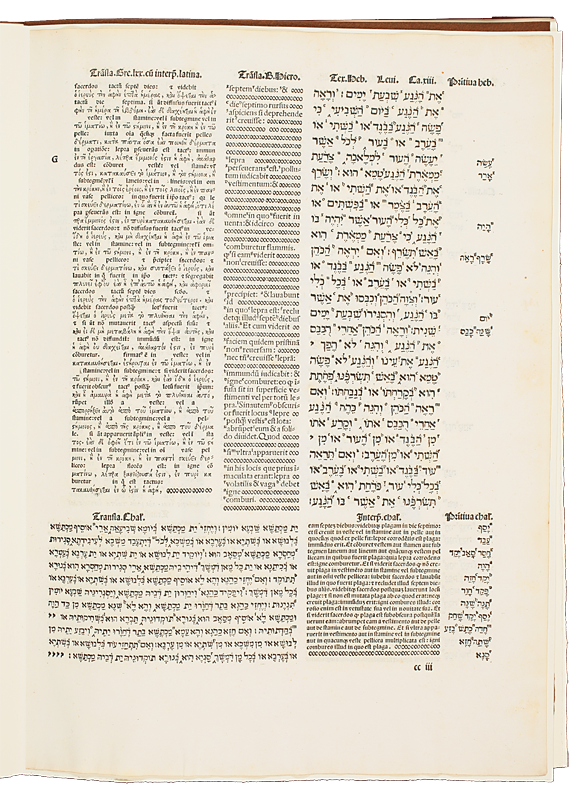

A Leaf from the Complutensian Bible (1516-1517)

Interest in the earliest languages of the Bible had grown substantially along with the 15th-century rise of Humanism. The drive to return to the early sources of Jewish and Christian history coincided with the rebirth of interest in ancient cultures in general. The six-volume Complutensian Bible, edited and published at the University of Madrid, was the first attempt to create a comprehensive polyglot (or multilingual) Bible. The Greek is reproduced with an interlinear Latin translation, while the Hebrew is referenced to the Latin with superscript letters.

The Most Beautiful Polyglot Bible

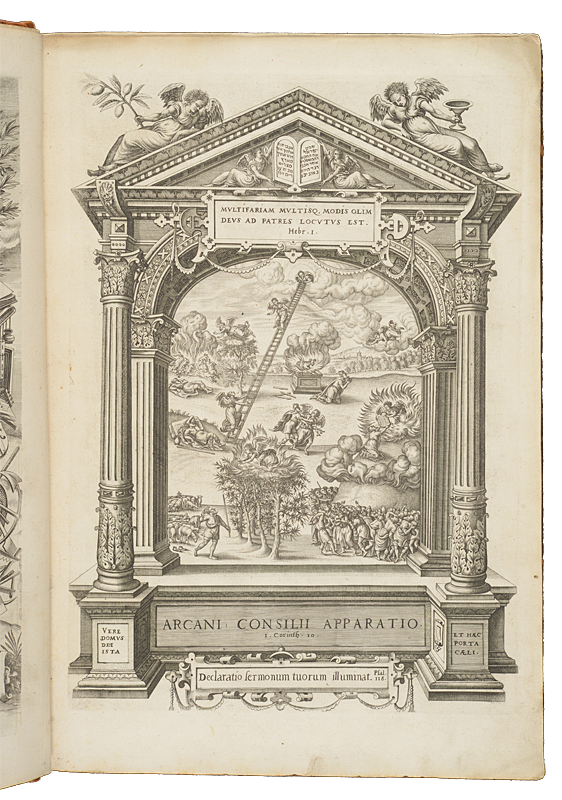

The Plantin or Antwerp Polyglot (1569-1572)

The second major polyglot Bible was printed in Antwerp by Christopher Plantin (ca. 1520-1589), the most important Belgian printer of the late 16th century. Overseen by Benito Arias Montano (1527-1598), the text was reproduced in Greek, Hebrew and Aramaic (with Latin translations) for the Old Testament and in Greek and Syriac (with Latin translations) for the New Testament. The eight-volume edition was dedicated to Philip II of Spain, and is considered one of the most beautiful books ever printed.

More Languages Than You Can (Probably) Read

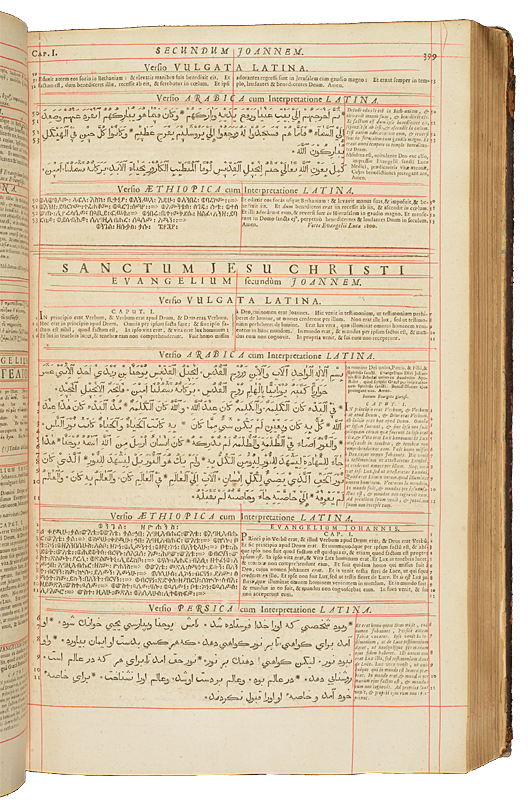

The London Polyglot (1657)

The six-volume Biblia Sacra Polyglotta (commonly called the London or Walton Polyglot) is the last of the larger full-Bible polyglot editions. It was produced in London from 1654 to 1657 by Thomas Roycroft and edited by Brian Walton. The New Testament text includes (on facing pages and with matching Latin translations) Greek, Syriac, Arabic, Persian, and Ethiopic. The Old Testament has Hebrew and Samaritan in place of the Syriac and Ethiopic.

Early English Translations of the Bible

Partial translations of the Bible into English date back to the early Middle Ages, including one into Anglo-Saxon by the Venerable Bede. Early modern translation into English begins in the late 14th century with John Wycliffe (executed in 1384) and his followers. Along with Jan Hus (ca. 1369-1415), Wycliffe is often included as a direct predecessor to the 16th-century Reformers.

Under the influence of Luther and Erasmus, William Tyndale (ca. 1494-1536) translated the New Testament from Greek and Hebrew into English. The English ban on Bible translation forced him to hide on the continent, as well as publish in secret. After Tyndale’s arrest (May 1535), Miles Coverdale added his own translations (chiefly from German and Latin) to publish the first full English Bible (1535). Tyndale’s work appeared again in the “Matthew’s Bible” (1537), which was succeeded by the “Great Bible” (1540), the Geneva Bible (1560), the Douai-Rheims Bible (1582/1609-1610), and finally by the King James Bible (1611).

The First Complete Bible in English

The Coverdale Bible (1535)

On May 21, 1535, the leading English Bible translator, William Tyndale (1494-1536), was arrested by imperial authorities in Antwerp (modern-day Belgium). Also living there was another Englishman, Miles Coverdale (1488-1569), who drew upon Tyndale’s translations, as well as Latin and German sources, to translate and publish the first full Bible translation into English. As it was still illegal to publish an English Bible in England, it appeared without city or publisher name. Today it is generally held that the Coverdale Bible was published in Antwerp.

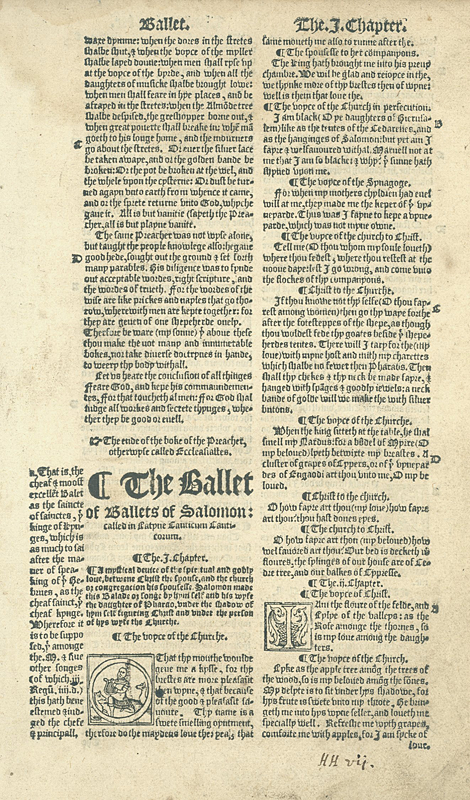

Not “Ballet” but Ballad!

Opening to the Song of Songs from a Reprint of the Matthew Bible (1549)

Two years after Coverdale’s first Bible appeared, another translation attributed to “Thomas Matthew” was published by Tyndale’s friend, John Rogers (1505-1555). This version combined the translations of Tyndale, Coverdale and some of Rogers’ own work. There is disagreement about the pseudonym “Matthew,” which has been taken to refer to either Rogers himself or to William Tyndale, who was still considered dangerous in England. Ultimately, both Tyndale and Rogers were martyred for their “dangerous” translations.

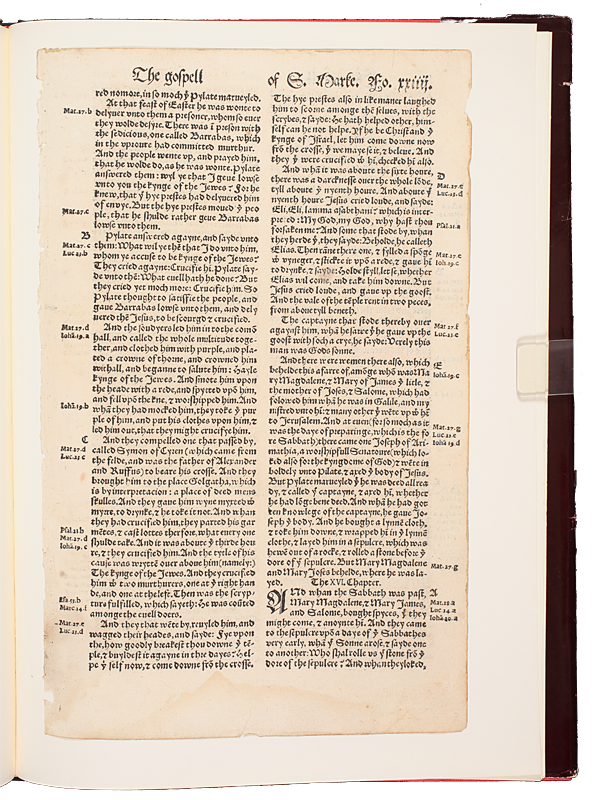

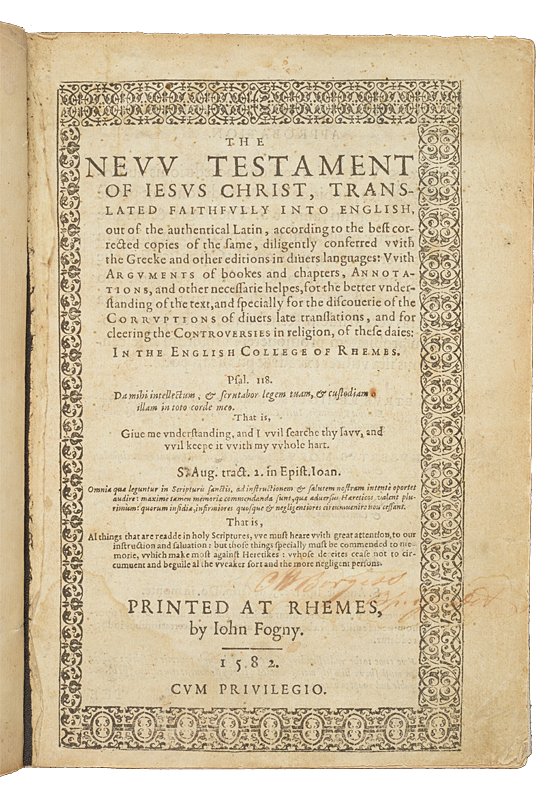

The Catholic Response

The Rheims New Testament (1582) and Douay Old Testament (1609-1610)

After Elizabeth I ascended to the English throne (1558), a Catholic English college was founded by William Allen (1532-1594) at the recently established University of Doway (also Douai or Douay, modern-day France). One important product of this refugee community was the translation of the New Testament (1582) and the Old Testament (1609-1610). This is the first English Bible translation intended specifically for Roman Catholics and was outlawed in England for over a century.

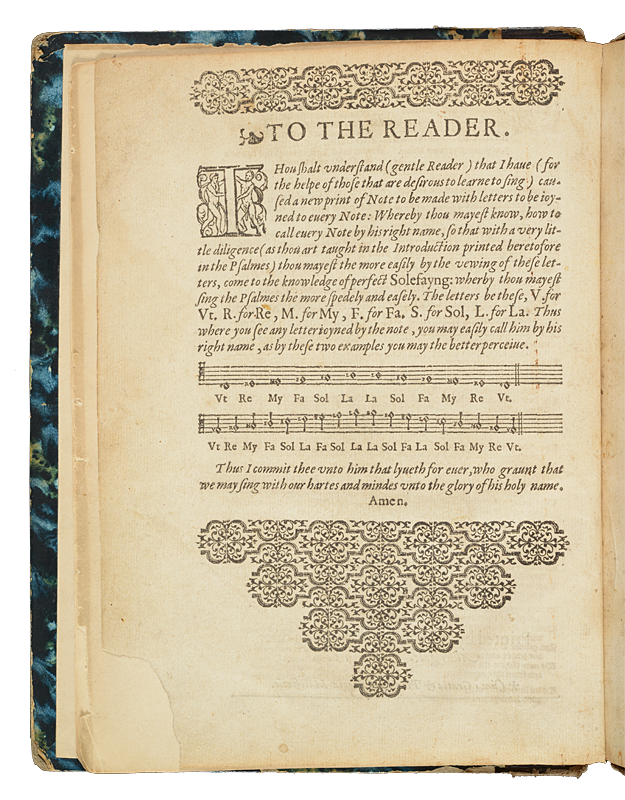

Psalms for Everyday

Sternhold’s Metrical Version of the Psalms (1584)

Thomas Sternhold (1500-1549) and John Hopkins (died 1570) were the principal authors of this Psalm collection in versified English, which became a standard part of worship life in early modern England—often being bound with copies of the Book of Common Prayer and the Geneva English Bible. While these translations did not originate in Geneva, they were greatly edited there and gained greatest circulation in this edited version. The addition of music points to the liturgical and worship use of these Psalms.

The Definitive Version for Many

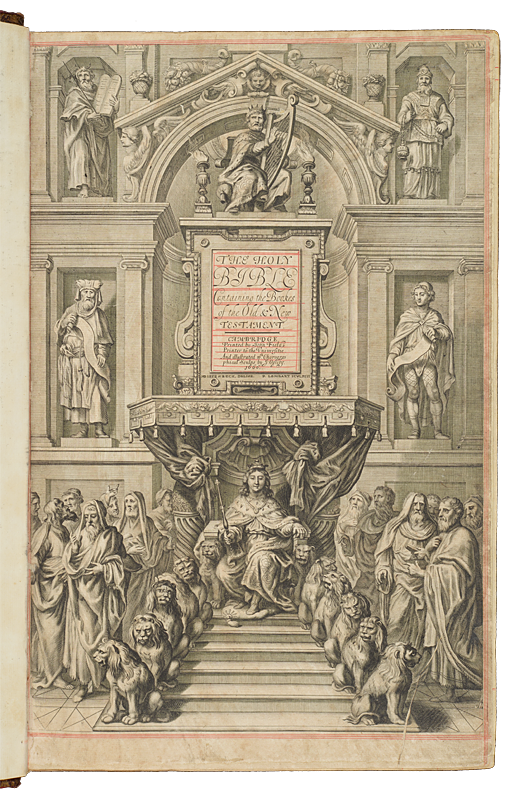

The King James Bible (1611)

This was the third English translation to be approved by English Church authorities, after the Great Bible (1539) and the Bishops’ Bible (1568). Saint John’s has several leaves from the earliest editions of this Bible (between 1611 and 1634), but the typography of these editions is so similar that precise identification is quite difficult. The earliest complete copies at Saint John’s date from 1657 and 1660; while this one is extra-large, some of the others are small, pocket-size editions.

Supporting the Study of the Bible

Already in the earliest days of the Christian Church, there was a need to explain Biblical texts and create commentaries on them. Some of the earliest commentators on the Bible, such as Augustine or Gregory, were studied throughout the Middle Ages, and over time, several of their works were compiled into larger glosses or commentaries like the Glossa Ordinaria and the Catena Aurea (Thomas Aquinas).

The Reformation ushered in a whole new set of commentaries and other secondary resources, especially with new readings based on the original languages. While many popular medieval authors continued to be printed in the 16th century (e.g. Denys the Carthusian, Rupert von Deutz), their works began to fade from view as newer collections of commentaries, concordances, sermons, etc. were authored by both Protestants and Catholics. Several of the leading Reformers, such as Luther, Calvin and Melanchthon, made major contributions to Biblical studies through their commentaries.

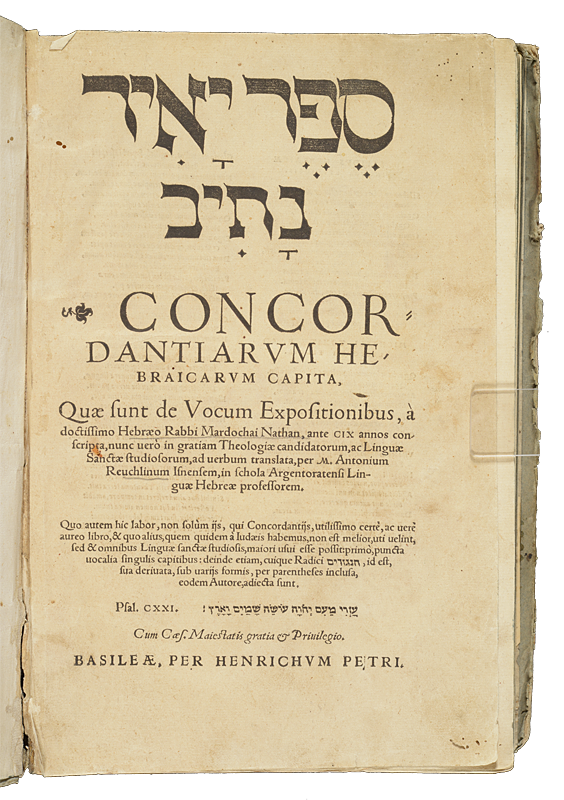

Hebrew Concordance and Lexicon

The Sefer ya’ir nativ (1556)

Isaac Nathan ben Kalonymus (14th-15th century), also known as Mordecai Nathan, compiled his Hebrew Biblical concordance in the 1430s and 1440s. Later Christian Hebraicists, like Anton Reuchlin (active 1554-1589) added Latin translations. First published in Venice in 1523, this edition comes out of areas sympathetic to the Geneva Reformation. Anton Reuchlin’s uncle, Johann Reuchlin (1455-1522) was the most famous German Christian Hebraicist in the early 16th century and even defended Hebrew books against confiscation and destruction.

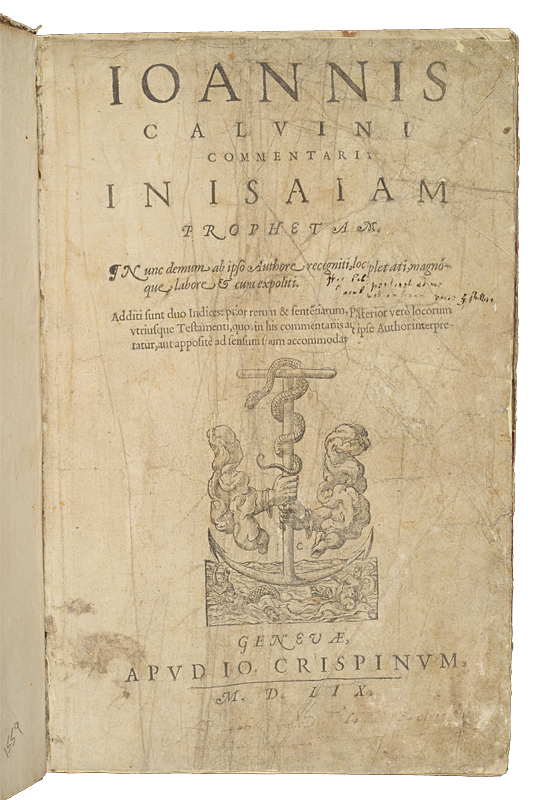

Reformed Perspectives on the Bible

Calvin’s Commentary on Isaiah (1559)

Jean Calvin was not only the leader of the Geneva branch of the Reformation, but he was himself a Biblical scholar and commentator. He wrote commentaries on parts of both the New and Old Testaments, including the Epistles, the Pentateuch, Psalms, Joshua, and Isaiah. Many of these grew out of his lectures on the Bible. He prefaced the first edition of the Isaiah commentary (1551) with a letter to King Edward VI of England, and added a letter to Queen Elizabeth I in this edition, which is also dedicated to Edward VI.

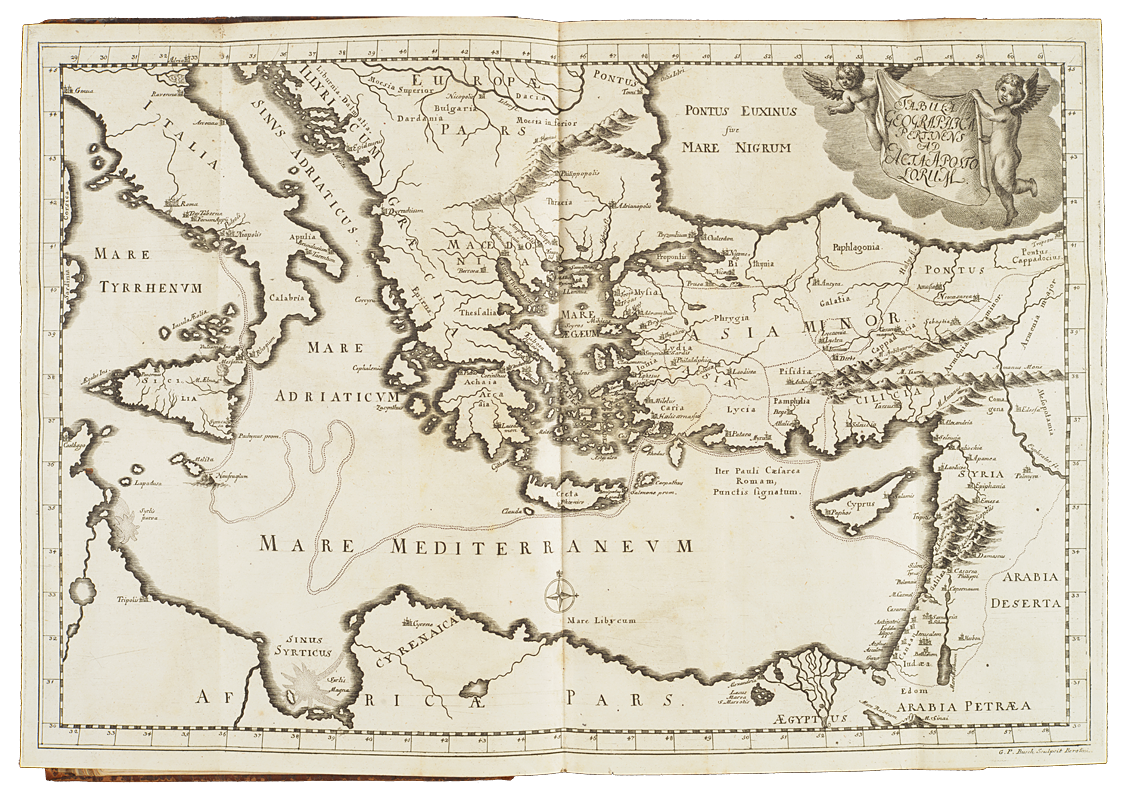

A Truly Comprehensive Explanation

Lindhammer’s Commentary on the Acts of the Apostles (1725)

This giant volume is dedicated entirely to the understanding of one book of the New Testament—the Acts of the Apostles. The author dedicated this to Carl Hildebrand von Canstein (1667-1719), who had published his own nine-volume harmony of the Gospels, and who had founded the Cansteinische Bibelanstalt (Halle, Germany) which is the oldest Bible society in the world. The Society’s immediate goal was to produce inexpensive Bible editions to promote its availability to all.

A Collection of Several Patristic Authorities

Leaf from the 1470 Catena aurea (Thomas Aquinas)

The medieval compilation called the Catena aurea provides a commentary on the Gospels, using brief selections from Augustine, Eusebius, Gregory and other patristic writers. A full volume of the Catena Aurea (in a later printing) is on display earlier in this exhibit.

Depicting the Bible in Woodcuts and Engravings

Popular reception of the Bible during the Reformation was heavily influenced by the visual depictions of Biblical stories and characters. The closest of these artistic treatments to the printed book were woodcut illustrations (chiefly in the 15th and 16th centuries) and intaglio prints (later 16th and 17th centuries). Such illustrations were perfect for including within the Bibles and other devotional works. As we saw earlier in the King James’ Bible (1660), some plates even have captions in multiple languages that make it possible to market them in several different countries and linguistic regions.

Some plates stand by themselves, such as a series depicting the Lord’s Prayer (AAP1483-AAP1490) and another that provides Biblical examples for the Beatitudes (AAP1085-AAP1091).

Such visual arts were both widely circulated and much utilized by all sides in the religious and political conflicts of the 16th and 17th centuries. Many images had great satirical effect, like the famous woodcut in Luther’s September Bible (1522) showing the papal tiara on the Whore of Babylon in the Book of Revelation. The agility of the printing industry in responding to the needs of the time firmly established its cultural importance.

The Bible in Visual Form

The Beatitudes – Engravings (ca. 1585)

This collection depicting the Beatitudes was published about 1585 in the Low Countries. The art of engraving, and in particular engravings of Biblical scenes, flourished in northern Europe in the late 16th and into the 17th centuries. The actual depictions use scenes from the Bible to portray the message of each Beatitude.

- Blessed are the poor in spirit, theirs is the kingdom of heaven (Job learns of the disasters that have befallen him)

- Blessed are those who weep, for they shall be consoled: Woman washing Jesus’ feet with her hair and tears

- Blessed are the meek, for they shall inerit the earth: Miriam and Aaron approach Moses and Zipporah

- Blessed are the merciful, for they shall obtain mercy: Tobit and corporal works of mercy

- Blessed are the pure of heart, for they shall see God: Annunciation with Mary and Gabriel

- Blessed are the peacemakers, they shall be called children of God: Abigail placates David’s wrath

- Blessed are they who are persecuted for justice, theirs is the kingdom of heaven: Stoning of Saint Stephen

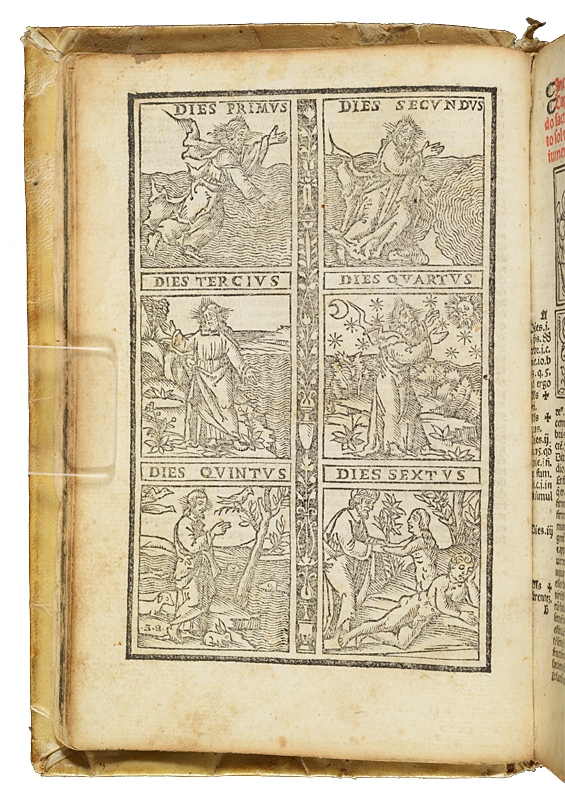

Six out of Seven Days of Creation

Latin Bible Published by Lucantonio Giunta (1519)

Lucantonio Giunta (1457-1538) was one of the most successful printer/publishers of his day, with business and family connections across Europe, and this is the first Bible printed under his auspices. At the opening of the Book of Genesis, the first six days of Creation are represented in a full-page woodcut. Saint John’s also has a folio Latin Bible (1513) with a very similar woodcut as the opening to the text. Unlike many later Bibles (both Catholic and Protestant), this one has no illustrations for the Book of Revelation.

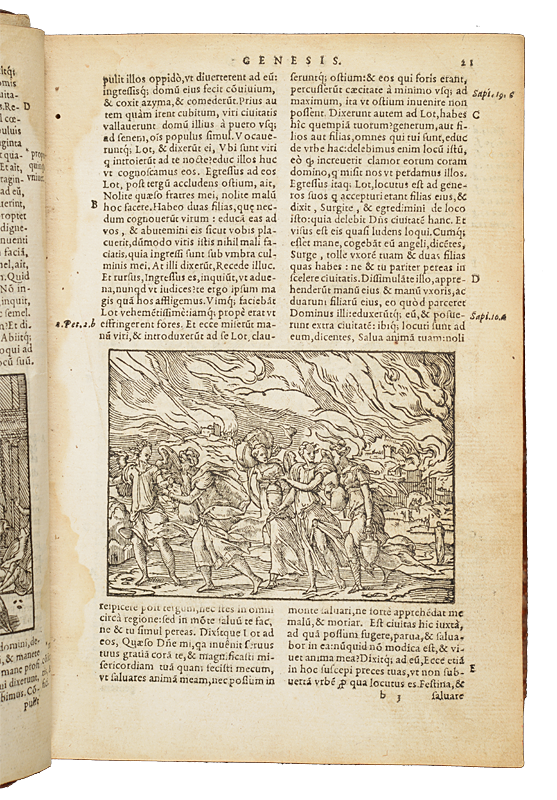

A Latin Bible from a Protestant Stronghold

Lyons Bible with Woodcuts by Bernard Salomon (le “petit Bernard”)

Lyons, in southern France close to Geneva, became a leading center for printing during the 16th century. Famous printers like Jean de Tournes, Sebastian Gryphius, and Guillaume Roville printed all manner of books in multiple languages. Starting in the 1550s, Jean de Tournes and his family published several editions of the Latin Bible (based on Robert Estienne’s editions) with woodcut illustrations by Bernard Salomon, noteworthy especially for the great detail packed into a very small space.

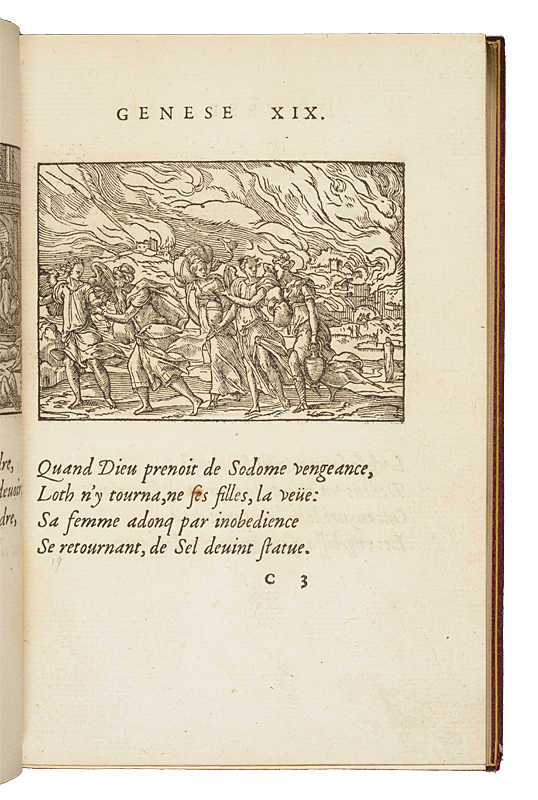

Preparing for New Bibles

Woodcut Bible Illustrations by Bernard Salomon (1553)

These woodcuts, finely printed in 1553, were later used in a full-text Bible from Lyons (also in this case) as well as at least one other edition from 1569 in the Saint John’s collections. Compare the quality of the impression between this copy and the 1558 Lyons Bible.

Curator(s)

Dr. Matthew Z. Heintzelman

Credits

Special thanks for their contributions to Tim Ternes, who installed the original exhibition in 2017; Katherine Goertz, who helped locate and identify materials from the Arca Artium Art Collection; David Calabro, who provided an improved romanization for the title of the Syriac New Testament; Wayne Torborg and Mary Hoppe, who provided the digital photos throughout the exhibition; and to John Meyerhofer, who prepared the online version.

Bibliography

Rebirth, Reform, and Revision

Late Medieval and Early Modern Sources on the Bible in Special Collections at HMML/Saint John’s University: a selection

I. Bible Manuscripts

Mabon Book of Hours, 15th century. SJU Ms. 1, Saint John’s Rare Books. https://w3id.org/vhmml/readingRoom/view/510541

Latin New Testament, ca. 1300. SJU Ms. 12, Saint John’s Rare Books. https://w3id.org/vhmml/readingRoom/view/510560

Gospel of Luke, fragment, 13th century. Ms. Frag. 19, HMML Special Collections. https://w3id.org/vhmml/readingRoom/view/519099

Latin Bible, fragment. Arca Fragment 26 (aap1306), Arca Artium Rare Book Collection. https://w3id.org/vhmml/readingRoom/view/534362

Gospel of Matthew, fragment. HMML Ms. 2, HMML Special Collections. https://w3id.org/vhmml/readingRoom/view/510576

II. Printed Bibles in Exhibition

Bibles, Polyglot (by date)

Psalterium, Hebraeum, Graecum. Arabicum, & Chaldaecum: cum tribus Latinis interpretatonibus & glossis. [Genoa]: Petrus Paulus Porrus, for Nicolaus Justinianus Paulus, 1516. Arca Artium Rare Book Collection. https://w3id.org/vhmml/readingRoom/view/511689

Nouum Testamentum omne multo quàm antehac diligentius ab Erasmo Roterodamo recognitum. Basel: Johann Froben, 1519. Arca Artium Rare Book Collection.

Basil Hall. The great polyglot Bibles: including a leaf from the Complutensian of Acalá, 1514-17. San Francisco: Book Club of California, 1966. Arca Artium Rare Book Collection.

Biblia Sacra Hebraice, Chaldaice, Graece, & Latine: Philippi II. Reg. Cathol. pietate, et studio ad Sacrosanctae Ecclesiae usum. Antwerp: Christopher Plantin, 1569-1572. Arca Artium Rare Book Collection.

Biblia sacra polyglotta: complectentia textus originales, Hebraicum, cum Pentateucho Samaritano, Chaldaicum, Græcum. Versionumque antiquarum, Samaritanæ, Græcæ LXXII Interp., Chaldaicæ, Syriacæ, Arabicæ, Æthiopicæ, Persicæ, Vulg. Lat. quicquid comparari poterat. London: Thomas Roycroft, 1657. Saint John’s Rare Books.

Bibles, Arabic

Al- Inǵīl al-muqaddas li-rabbinā Jasūʻ al-Masīḥ ... Mattā wa-Marqus wa-Lūqā wa-Jūḥannā; Evangelium Sanctum Domini nostri Iesu Christi, conscriptum a quatuor evangelistis sanctis. Rome: Typographia Medicea, 1590/1591. Saint John’s Rare Books. https://w3id.org/vhmml/readingRoom/view/510574

Bibles, English (by date)

Allen Paul Wikgren. A leaf from the first edition of the first complete Bible in English, the Coverdale Bible, 1535. San Francisco: Book Club of California, 1974. Arca Artium Rare Book Collection.

Here begynneth the Pystles and Gospels of euery Sonday and holy daye in the yere. [Rouen : N. le Roux], 1538. Bound with the Primer in English and Latin (1538). Arca Artium Rare Book Collection.

The Byble that is to say all the holy Scripture: in whych are contayned the Olde and New Testamente, fragment. London: S. Mierdman for John Daye and William Seres, 1549. Arca Artium Art Collection.

The Nevv Testament of Iesvs Christ: translated faithfvlly into English, out of the authentical Latin, according to the best corrected copies of the same … Reims: Jean de Foigny, 1582. Arca Artium Rare Book Collection.

Thomas Sternhold. The whole booke of Psalmes. London: John Daye, 1584. Saint John’s Rare Books.

The Holie Bible faithfully translated into English, out of the authentical Latin, Diligently conferred with the Hebrew, Greeke, and other editions in divers languages. Douai: Laurence Kellam, 1609-1610. Arca Artium Rare Book Collection.

Thomas Sternhold, et al. The Whole Booke of Psalmes. London: Robert Young, 1633. Bound with the Book of Common Prayer; A Briefe Concordance or Table to the Bible of the Last Translation; and: The Way to True Happinesse … (all dated 1633). HMML Special Collections.

The Holy Bible : Contayning the Old and New Testaments, newly translated out of ye originall tongues, and with ye former translations diligently compared and revised. London (?): John Field, 1657. https://w3id.org/vhmml/readingRoom/view/534330

The Holy Bible, Containing the Bookes of the Old & New Testament. Cambridge: John Field, 1660. Arca Artium Rare Book Collection.

The Holy Bible, containing the Old Testament and the New, newly translated out of the original tongues, and with the former translations diligently compared and revised. London: Henry Hills and John Field, 1660. Saint John’s Rare Books. https://w3id.org/vhmml/readingRoom/view/519072

Bibles, French (by date)

Le premier volume de la Bible en francois ; Le second volume de la Bible en francoys. Paris: [Pierre II Regnault], 1544-1546. Arca Artium Rare Book Collection.

La Bible, qui est toute la Saincte Escriture du Vieil & du Nouueau Testament: Autrement l’anciene & la nouuelle alliance. Geneva, 1588. Saint John’s Rare Books.

Les Pseaumes de David mis en rime françoise. Sedan: Jean Jannon, 1623. Arca Artium Rare Book Collection.

Bibles, German (by date)

[Bible in German], fragment. Nuremberg: Anton Koberger, 1483. Arca Artium Art Collection.

[Bible in German], fragment. Strasbourg: Johann Grüninger, 1485. Arca Artium Art Collection.

Bibell, Alle Bücher alts und news Testaments, translated by Johann Dietenberger. Cologne: Gerwin Calenius and the heirs of Johan Quentel, 1572. Saint John’s Rare Books. https://w3id.org/vhmml/readingRoom/view/519069

Biblia, das ist, Die gantze heilige Schrifft deutsch, translated by Martin Luther. Wittenberg: August Boreck, 1626. Arca Artium Rare Book Collection.

Bibles, Greek (by date)

Hē kainē diathēkē. Paris: Simon de Colines, 1534]. Arca Artium Rare Book Collection.

Tēs Kainēs Diathēkēs hapanta; Nouum Testamentum: ex Bibliotheca Regia. Paris: Robert Estienne, 1546. Arca Artium Rare Book Collection.

Tēs Kainēs Diathēkēs hapanta. Euangelion kata Matthaion. Kata Markon. Kata Loukan. Kata Iōannēn. Praxeis tōn Apostolōn.; Nouum Iesu Christi D.N. Testamentum. Paris: Robert Estienne, 1550. Arca Artium Rare Book Collection.

Bibles, Italian

Il Nuovo ed eterno Testamento di Giesu Christo. Lyons: Jean de Tournes and Guillaume Gazeau, 1556. Arca Artium Rare Book Collection.

Bibles, Latin (by date)

A. Edward Newton. A Noble Fragment: Being a Leaf of the Gutenberg Bible, 1450-1455. New York: Gabriel Wells, 1921. College of Saint Benedict Rare Books.

Psalterium Benedictinum, fragment Mainz: Johann Fust and Peter Schoeffer, 1459. Arca Artium Art Collection.

Biblia Latina [with the Glossa Ordinaria]. Strasbourg: Adolph Rusch for Anton Koberger, 1481. Arca Artium Rare Book Collection.

Biblia Integra. Basel: Johann Froben, 1491. Arca Artium Rare Book Collection.

Biblia cum concordantijs Veteris et Noui Testamenti et sacrorum canonum: summa cum diligentia reuisa correcta et emendata. Venice: Lucantonio Giunta, [15 October 1519]. Saint John’s Rare Books.

In hoc libello contenta Psalterium Dauidicum cum aliquot canticis ecclesiasticis, litanie, hymni ecclesiastici. Paris: C. Chevallon, 1536. Arca Artium Rare Book Collection. https://w3id.org/vhmml/readingRoom/view/534504

Biblia Sacra vtrivsqve Testamenti, et Vetvs qvidem post omnes omnivm hactenus aeditiones : opera D. Sebast. Mvnsteri euulgatum, & ad Hebraicam ueritatem quoad fieri potuit redditum. Zurich: Christoph Froschauer, 1539. Saint John’s Rare Books.

Biblia Sacra ad optima quaeque veteris, ut vocant, tralationis exemplaria summa diligentia, parique fide castigata. Lyons: Jean de Tournes, 1558. Arca Artium Rare Book Collection.

Biblia Sacra Vvlgatae editionis. Rome: Ex typographia Vaticana, 1598. Arca Artium Rare Book Collection.

Bibles, Slavonic

Biblīa sirēch knigy vetkhago i novago zavĕta po i͡azykū slovenskū. Ostroh (Ukraine): Ivan Fyodorov, 1581. Arca Artium Rare Book Collection. https://w3id.org/vhmml/readingRoom/view/520945

Bibles, Syriac

Ktābā d-ʼEwangeliyon qadíšā d-Māran w-ʼAlāhan Yešúʻ Mšíḥā: Liber sacrosancti evangelii de Iesv Christo Domino & Deo nostro. Vienna: Michael Cymermannus, 1555. Arca Artium Rare Book Collection. https://w3id.org/vhmml/readingRoom/view/520958

III. Other Printed Works in this Exhibition

Théodore de Bèze. Les vrais povrtraits des hommes illvstres en piete et doctrine. [Geneva]: Jean de Laon, 1581. Arca Artium Rare Book Collection. https://w3id.org/vhmml/readingRoom/view/520948

Jean Calvin. Commentarii in Isaiam prophetam. Geneva: Jean Crispin, 1559. Saint John’s Rare Books.

Johann Ludwig Lindhammer. Der von dem H. Evangelisten Luca beschriebenen Apostel-Geschichte ausführliche Erklärung und Anwendung. Halle: Waisenhaus, 1725. Saint John’s Rare Books.

Martin Luther. Colloquia, oder Tischreden Doctor Martini Lutheri. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Schmid and Sigmund Feyerabend, 1569. Saint John’s Rare Books.

Martin Luther. Tomus primus [-quartus et idem ultimus] omnium operum. Jena: Christian Rödinger, 1556-1570. Saint John’s Rare Books.

Mordecai Nathan. Sefer ya’ir nativ : Concordantiarum Hebraicarum capita. Basel: Heinrich Petri, 1556. Saint John’s Rare Books.

Nicholas of Lyra. Postillae perpetuae in Vetus et Novus Testamentum, vol. 3 Rome: Conrad Sweynheim and Arnold Pannartz, 1470. Arca Artium Rare Book Collection.

Ordnung des Herren Nachtmal: so man die Messz nennet, sampt der Tauff vnd Insegung der Ee. [Strasbourg: Johannes Schwan], 1525. Saint John’s Rare Books. https://w3id.org/vhmml/readingRoom/view/520756

Claude Paradin and Bernard Salomon. Quadrins historiques de la Bible. Lyons: Jean de Tournes, 1553. Arca Artium Rare Book Collection. https://w3id.org/vhmml/readingRoom/view/534297

Thomas Aquinas. Diui Thome Aquinatis continuum in librum ewangelij secundum Mattheum. Venice: Andreas de Asula and Thomas de Alexandria, 1486. Saint John’s Rare Books.

Thomas Aquinas. Catena aurea. Rome: Conrad Sweynheim and Arnold Pannartz, 1470. Fragment. Arca Artium Rare Book Collection.