Rebirth, Reform, And Revision

Rebirth, Reform, and Revision

Reading the Bible during the Reformation — Part 1

Understanding and relating the stories of the Bible have been vitally important to Christians for nearly two millennia. Each society and generation has found new ways to approach these dual missions, however. Five hundred years ago, Martin Luther initiated a series of changes for Western Christianity that both offered a radical departure from the received modes of interaction with the Bible and complemented broader changes in the intellectual and spiritual approaches to living in accord with Biblical teaching. The two parts of this exhibit offer a brief overview of Biblical study and reception during the 15th to the 17th centuries, encompassing the received traditions for Bible study from the later Middle Ages, the tumultuous years of the 16th-century Reformation, and new modes for understanding the Bible in the Protestant and Roman Catholic communities. Our story proceeds roughly chronologically, starting in Part I with Bible manuscripts and fragments from the 14th and 15th centuries, and then continues with the advent of printing (including a leaf from the Gutenberg Bible). Part II begins with Martin Luther’s challenge to the authority of the Catholic Church and his goal of presenting the Bible in the language of the common folk. Then we turn to vernacular treatments of the Bible across Europe, the search for the purest form of the text and the early transmission of the Bible in English. Finally, we see examples of the flourishing Biblical art in 16th- and 17th-century woodcuts and engravings. The scope of this exhibit is limited to the change in Biblical scholarship and reading during this period. With that in mind, we must acknowledge that a large part of the story of the Reformation had to be omitted—especially its impact on European (and worldwide) society in political, social, educational, and economic terms. The collections at Saint John’s University contain many contemporaneous resources for the study of the Reformation, however those resources fell outside of the boundaries of the current exhibition, which features works from HMML's rare books and manuscripts collections.

Centuries of Handwriting

In their earliest form, the Bible stories were passed on orally from one generation or community to another. This form of transmission eventually gave way to handwriting, first on papyrus, then parchment (animal skins), and then paper. For several centuries the only way to make a new Bible was to copy it from another volume. However, just as oral versions can be subject to faulty memories or poetic elaboration, handwritten texts can also change over time and from one copier to the next. It was also impossible to compare two different Bibles that were located hundreds of miles apart to check for accuracy. The process of copying was not entirely arbitrary, however, as sacred texts like the Bible were usually corrected after they were copied in order to assure higher accuracy. Modern scholars of the Bible strive for greater accuracy by consulting all pertinent early manuscripts, the most famous of which include the Codex Sinaiticus and the Codex Vaticanus B (both 4th century).

He Composed much of the New Testament

Saint Paul

This woodcarving of Saint Paul comes from the southern Netherlands and dates from the early 15th century. He holds a book in one arm as a symbol of his role as an important author from the Bible; although much of his right hand is missing, it probably once held a sword. Completed in the International Gothic style (ca. 1360-1430), the statue is from a series of apostles in a wooden retable.

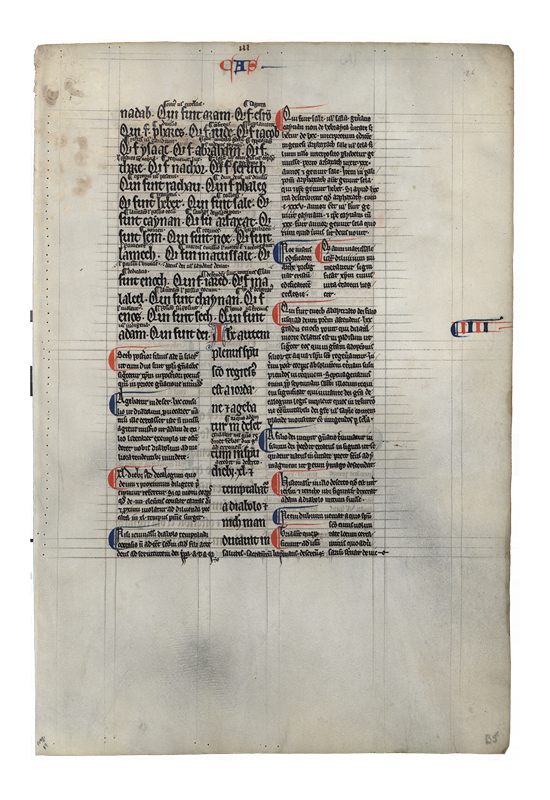

Reading the Written

Leaf from a 13th-century Glossed Bible

This leaf was cut out of a Latin Bible, copied in Paris about 1220-1230. The text is from the genealogy of Jesus in the Gospel of Luke. The elaborate layout uses a hierarchy of scripts to separate the Gospel text (largest script) and the surrounding and interlinear glosses (smaller scripts). Such compiled glosses became very common as a source for Biblical interpretation in the later Middle Ages. The first printed edition of the most common gloss appeared in 1480.

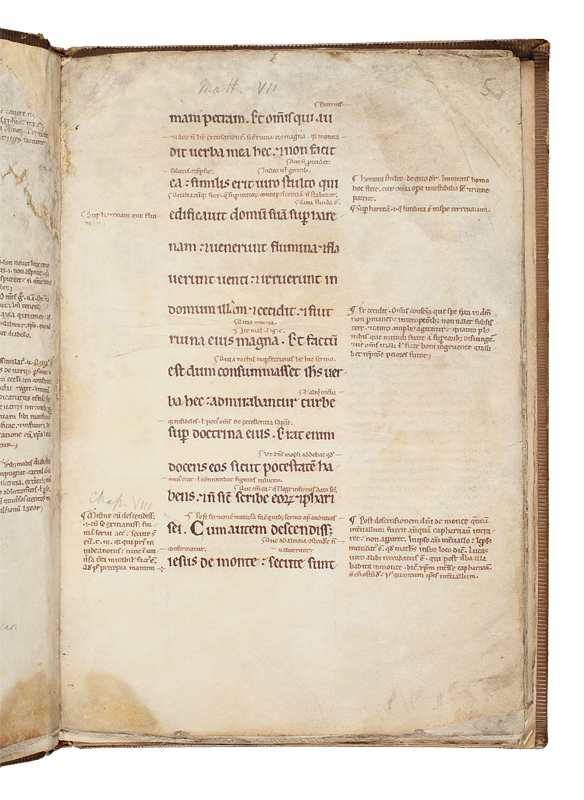

Remnants of the Gospel

Glossed New Testament (13th century)

Like the previous, glossed Bible, this beautiful fragment uses a hierarchy of scripts to separate Biblical text from commentary. The largest lettering in the middle column contains text from the Gospel of Matthew, chapter 7—including the parable of the wise man who builds his house on stone. The smaller text in the side margins contains commentary on this passage, along with tiny interlinear explanations. A modern hand has added the chapter numbers for quick reference, e.g., “Matt. VII.”

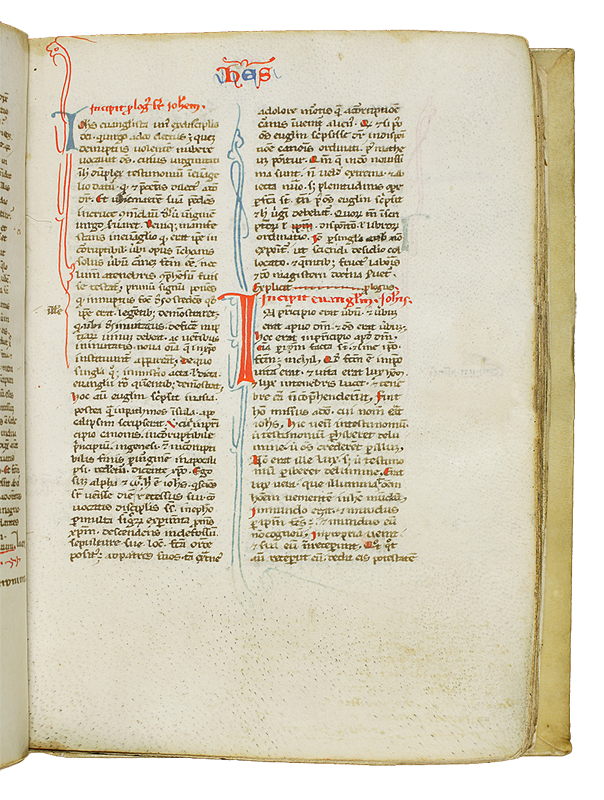

Small but Powerful

The New Testament in Latin (ca. 1300)

This entirely portable manuscript was probably prepared for a traveller, perhaps a mendicant preacher. Even though the handwriting is among the smallest one is likely to encounter, it is nevertheless relatively legible. There are even corrections in the margins to repair the copyist’s mistakes. There are neither page numbers nor verse numbers, while the primary guideposts for the reader are red and blue initials, some of which are quite elaborate.

The Bible in Everyday Life

The Mabon Book of Hours (15th century)

One of the more common ways for Bible texts to be “consumed” in the later Middle Ages was through prayer with a Book of Hours. Intended for the use of the laity, these highly ornamented prayer books include selections from the four Gospels as well as Psalms for prayers at different times of the day. Other standard parts of these books are a calendar, litany of saints and the office for the dead. Here we see the evangelist John (with his distinctive eagle) on the island of Patmos.

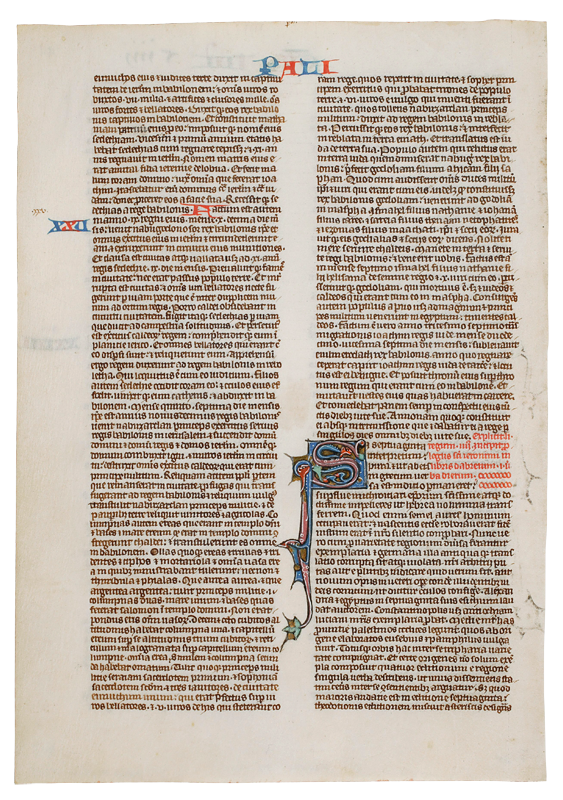

Not all were Glossed!

Leaf from a Latin Bible (mid-13th century)

As with most Biblical manuscripts, the codex from which this leaf has been removed did not include extensive glosses. The elaborate initial “S” in the second column marks the opening of Jerome’s preface to the first book of Chronicles—“Pali” in the heading is short for “Parali” or the first half of the word Paralipomena. The roman numeral XXV (25) in the left margin notes the start of the final chapter of 2 Kings. Initials, ink colors and marginalia were basic elements in medieval manuscripts for orienting readers.

Early Printing, Humanism, and Commentaries

Disruptive Technologies: Printing Comes to Europe

Today we are frequently confronted with technologies that seem to turn our world upside down overnight. Such changes were not so instantaneous in the 15th century, but Johann Gutenberg (ca. 1400-1468) made a lasting and deep mark on European culture with his radical new way to make books using movable type with a new kind of ink. His most important printed book was a large Bible that was finished about 1455. Within a few years, the new technology of printing had spread across Germany and into many other European countries. During the century after Gutenberg’s discovery, the design of the book changed radically, at first assuming the guise of the manuscripts it was replacing, but then developing special characteristics of its own: a title page with author, publisher and other information, folio or page numbers, and consistent use of colophons, catch words, signatures, etc. Between 1450 and the start of the 16th century, the book that was printed most frequently was the Bible, especially in Latin but also in other languages. It, too, underwent the same evolution as other printed books.

A New Beginning

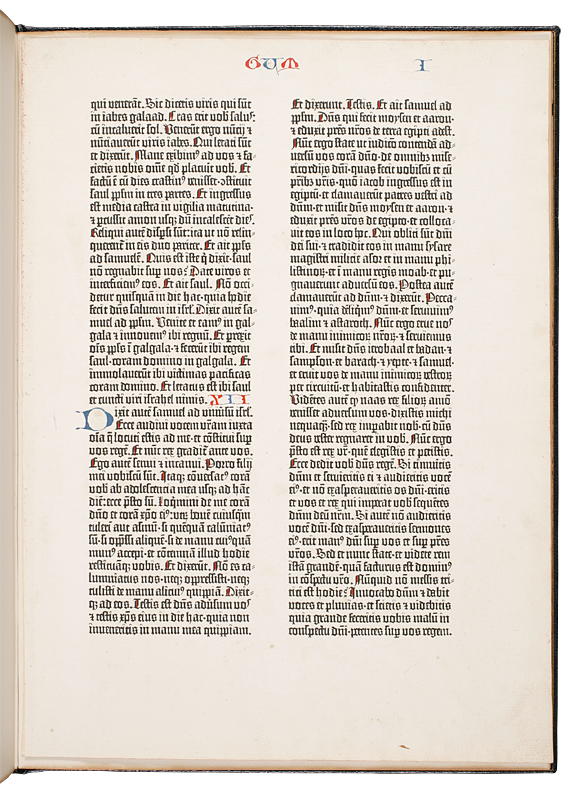

Leaf from the Gutenberg Bible (ca. 1450-1455)

Johannes Gutenberg (ca. 1400-1468) was a blacksmith and goldsmith in Mainz, Germany. He combined his background knowledge with other technology of his day, resulting in the first printing with movable type in the West. He was not in business for very long, but managed to print one true masterpiece—the 42-line Latin Bible printed between 1450 and 1455. For the first time it was possible to make multiple, nearly identical copies, which also reduced the cost for readers. His book still strongly resembles a manuscript, however.

Communal Prayers for Benedictines

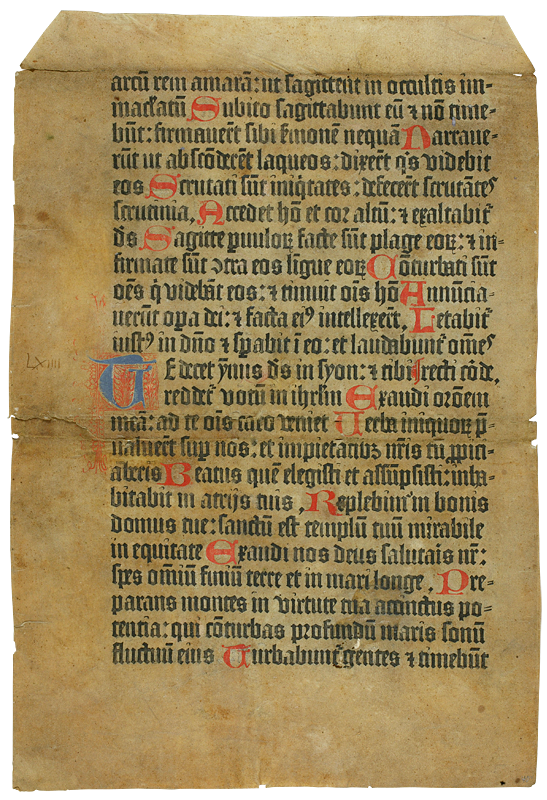

Leaf from the Benedictine Psalter (1459)

The Psalms have always played a central role in the prayer life of the Benedictines. For over fifteen centuries the monks have prayed and sung these powerful Biblical witnesses to God’s presence in human lives. As part of a 15th-century reform movement, a monastery in Mainz, Germany, commissioned the printing of a Psalter (collection of Psalms) from the successors to Johann Gutenberg’s printshop. This large leaf, printed on vellum, was later recycled in a book binding.

A 15th-century Scholarly Edition

Latin Bible with the Glossa Ordinaria (1480)

As with the glossed Bibles in the first case, this volume has differently sized typeface between the gloss and the original text. These massive Bibles—this copy probably had four volumes originally—could only be purchased by larger libraries (e.g. monastic, diocesan, or university) and did not circulate. Evidence from this volume point to use in a “chained” library, where the books would be attached to the desk with a metal chain. This type of publication supported the study of the received teachings on the Bible.

A Pocket Edition … for a Large Pocket

Octavo Latin Bible (1491)

This thick volume is from the first printed Bible edition to appear in an octavo format. While the word itself is not a size designation, a book in “octavo” format is usually smaller than one that is quarto or folio—the formats in which all previous printed Bibles had appeared. The small size (and exceedingly small print) makes this more of a personal copy than an institutional one. The cover is made of durable pigskin leather over wooden boards.

German Bibles Before Luther

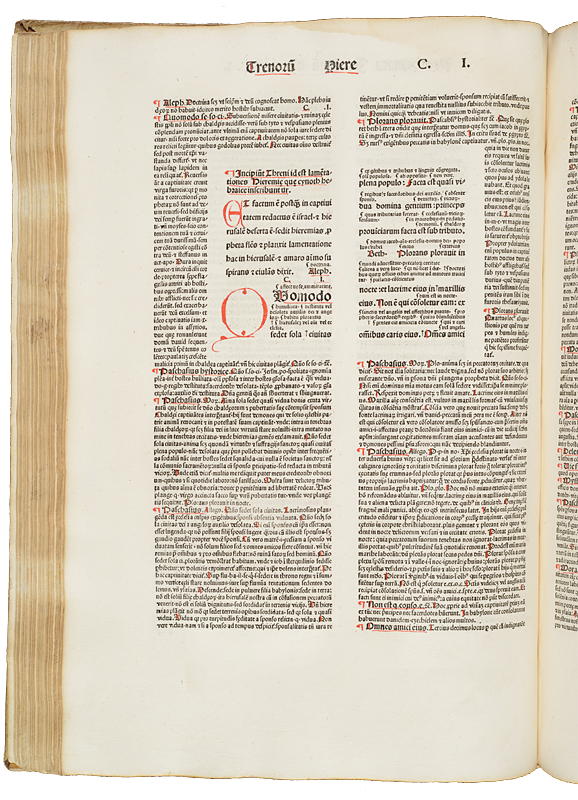

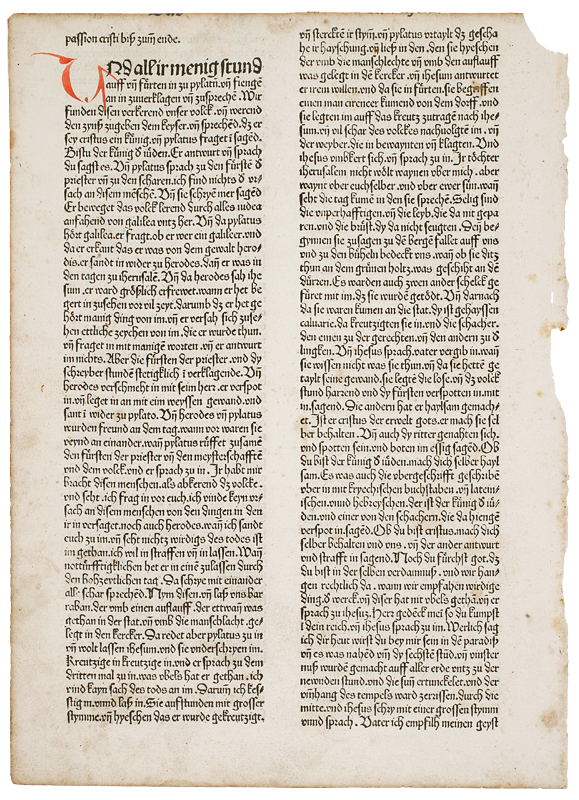

Leaves from the 1483 and 1485 German Bibles

Printed Bibles appear in German several times during the incunabula period (ca. 1455-1500). The first German edition was published by Johann Mentelin (ca. 1410-1478) in Strasbourg in 1466 and was reprinted thirteen times by various publishers. The text of these editions was based on the Latin Vulgate and presented word-for-word translations. Luther’s later innovations included the use of colloquial German and translation directly out of the source languages: Greek for the New Testament and Hebrew for the Old Testament.

Ad fontes – A Renewed Interest in Greek and Hebrew for Biblical Studies

Along with printing, the 15th century also saw the rise of the Renaissance in art and music, as well as Humanism in the scholarly world. The Humanists were a highly educated network of scholars across Europe who looked back for stylistic models in classical Antiquity, both in its culture and in writing or script. The study of the early Latin and Greek languages and literatures (e.g. Juvenal, Ovid, Terence, et al.) led also to a renewed interest in Hebrew and Biblical literature. The “Prince of the Humanists” was Desiderius Erasmus of Rotterdam (1466-1536) who maintained his own network of scholarly friends across Europe, including Thomas More in England and Johann Froben in Basel. The Reformers were especially indebted to Erasmus’ edition of the Greek New Testament for their own study, translation and preaching. While Erasmus often used his studies to challenge the Catholic Church, he remained a loyal member of it—seeking above all to improve the Catholic Church by following a “middle way” during the first decades of the Reformation.

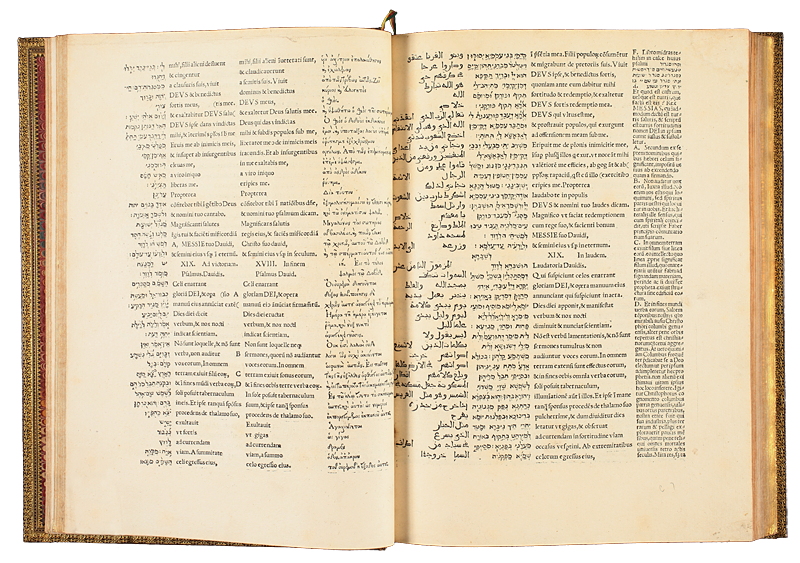

The First of a New Age in Biblical Studies

The Genoa Psalter (1516)

Edited by Agostino Giustiniani, the Genoa Psalter was the first of the polyglot (or multilingual) editions of Biblical texts, coming out the same year as Erasmus’ Greek/Latin New Testament. Giustiniani reproduces the Psalms in five languages: Hebrew, the Latin Vulgate, the Greek Septuagint, Chaldee (Biblical Aramaic), and Arabic. The Hebrew and Chaldee versions are accompanied by literal translations into Latin. Polyglot versions became one of the new tools for scholars to interpret the Bible and to refine the most accurate version of the text.

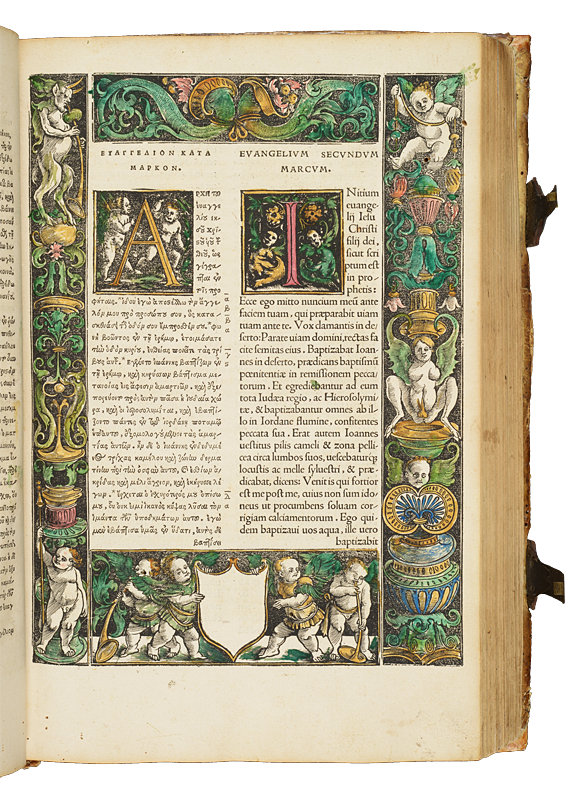

A Bestseller of its Time?

Erasmus’ Edition of the New Testament in Greek and Latin

While the Complutensian New Testament in Greek was printed already in 1514, the first published Greek New Testament was that of the famous humanist, Desiderius Erasmus (1466-1536) in 1516. Due to his haste in preparation, several errors were soon noted in the edition and a second edition appeared in 1519, correcting several of these errors. As this was a convenient size and relatively easy to obtain, it became the standard Greek version for much of the 16th century.

A Mother with Her Baby

Virgin Mary with the Child Jesus (Spain, 13th century)

While this Virgin and Child shows influence of French Gothic models (especially in the appearance in a standing position), the basic aesthetic of the piece is traditional Romanesque. Thus, this is a transitional piece pointing to the blossoming of Gothic art that would come soon.

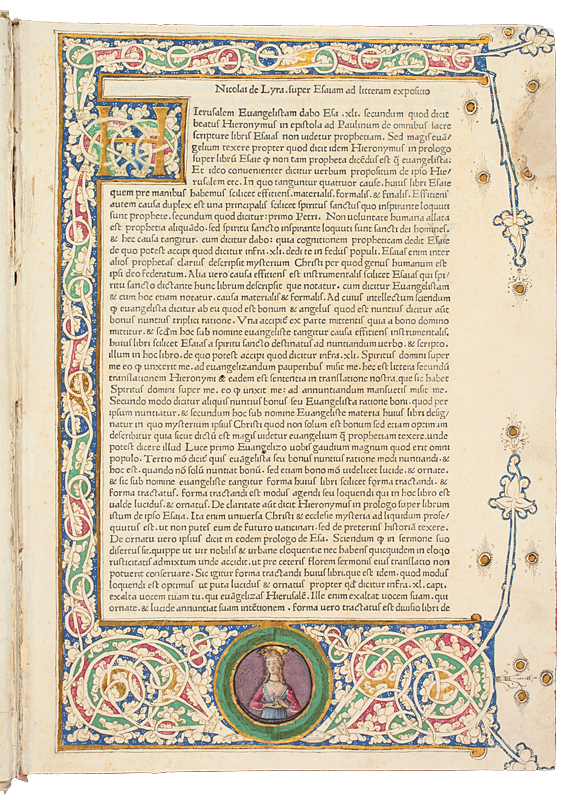

Looking Like a Humanist Manuscript

The Postilla of Nicholas of Lyra (printed 1471)

Nicholas of Lyra’s massive commentary on the Bible, the Postillae was first published in five volumes in 1471 by two German printers living in Rome. His approach to the text foreshadowed later development of textual criticism and a return to the source languages, especially Hebrew. Even Martin Luther was heavily influenced by Nicholas’ writings, praising his predecessor in the Tischreden (table talks).

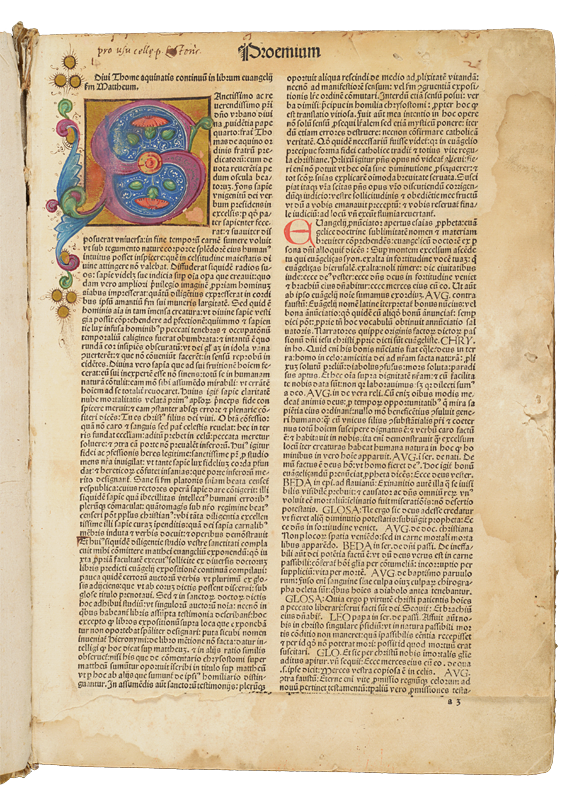

A “Golden Chain” of References

The Catena aurea of Thomas Aquinas (printed in 1486)

Composed of excerpts from previous commentators, the Golden Chain of Thomas Aquinas (1225-1274) is the most famous example of the literary genre called the “catena” or “chain.” It is by no means the only such chain in existence. This compilation makes use of works by Eusebius, Bede, Augustine, Cyril, Basil, Ambrose, and several other patristic authors. Although the popularity of this work faded somewhat during the course of the early Reformation, it continued to be published into the 19th and early 20th centuries.

Curator(s)

Dr. Matthew Z. Heintzelman

Credits

Special thanks for their contributions to Tim Ternes, who installed the original exhibition in 2017; Katherine Goertz, who helped locate and identify materials from the Arca Artium Art Collection; David Calabro, who provided an improved romanization for the title of the Syriac New Testament; Wayne Torborg and Mary Hoppe, who provided the digital photos throughout the exhibition; and to John Meyerhofer, who prepared the online version.

Bibliography

Rebirth, Reform, and Revision

Late Medieval and Early Modern Sources on the Bible in Special Collections at HMML/Saint John’s University: a selection

I. Bible Manuscripts

Mabon Book of Hours, 15th century. SJU Ms. 1, Saint John’s Rare Books. https://w3id.org/vhmml/readingRoom/view/510541

Latin New Testament, ca. 1300. SJU Ms. 12, Saint John’s Rare Books. https://w3id.org/vhmml/readingRoom/view/510560

Gospel of Luke, fragment, 13th century. Ms. Frag. 19, HMML Special Collections. https://w3id.org/vhmml/readingRoom/view/519099

Latin Bible, fragment. Arca Fragment 26 (AAP1306), Arca Artium Rare Book Collection. https://w3id.org/vhmml/readingRoom/view/534362

Gospel of Matthew, fragment. HMML Ms. 2, HMML Special Collections. https://w3id.org/vhmml/readingRoom/view/510576

II. Printed Bibles in Exhibition

Bibles, Polyglot (by date)

Psalterium, Hebraeum, Graecum. Arabicum, & Chaldaecum: cum tribus Latinis interpretatonibus & glossis. [Genoa]: Petrus Paulus Porrus, for Nicolaus Justinianus Paulus, 1516. Arca Artium Rare Book Collection. https://w3id.org/vhmml/readingRoom/view/511689

Nouum Testamentum omne multo quàm antehac diligentius ab Erasmo Roterodamo recognitum. Basel: Johann Froben, 1519. Arca Artium Rare Book Collection.

Basil Hall. The great polyglot Bibles: including a leaf from the Complutensian of Acalá, 1514-17. San Francisco: Book Club of California, 1966. Arca Artium Rare Book Collection.

Biblia Sacra Hebraice, Chaldaice, Graece, & Latine: Philippi II. Reg. Cathol. pietate, et studio ad Sacrosanctae Ecclesiae usum. Antwerp: Christopher Plantin, 1569-1572. Arca Artium Rare Book Collection.

Biblia sacra polyglotta: complectentia textus originales, Hebraicum, cum Pentateucho Samaritano, Chaldaicum, Græcum. Versionumque antiquarum, Samaritanæ, Græcæ LXXII Interp., Chaldaicæ, Syriacæ, Arabicæ, Æthiopicæ, Persicæ, Vulg. Lat. quicquid comparari poterat. London: Thomas Roycroft, 1657. Saint John’s Rare Books.

Bibles, Arabic

Al- Inǵīl al-muqaddas li-rabbinā Jasūʻ al-Masīḥ ... Mattā wa-Marqus wa-Lūqā wa-Jūḥannā; Evangelium Sanctum Domini nostri Iesu Christi, conscriptum a quatuor evangelistis sanctis. Rome: Typographia Medicea, 1590/1591. Saint John’s Rare Books. https://w3id.org/vhmml/readingRoom/view/510574

Bibles, English (by date)

Allen Paul Wikgren. A leaf from the first edition of the first complete Bible in English, the Coverdale Bible, 1535. San Francisco: Book Club of California, 1974. Arca Artium Rare Book Collection.

Here begynneth the Pystles and Gospels of euery Sonday and holy daye in the yere. [Rouen : N. le Roux], 1538. Bound with the Primer in English and Latin (1538). Arca Artium Rare Book Collection.

The Byble that is to say all the holy Scripture: in whych are contayned the Olde and New Testamente, fragment. London: S. Mierdman for John Daye and William Seres, 1549. Arca Artium Art Collection.

The Nevv Testament of Iesvs Christ: translated faithfvlly into English, out of the authentical Latin, according to the best corrected copies of the same … Reims: Jean de Foigny, 1582. Arca Artium Rare Book Collection.

Thomas Sternhold. The whole booke of Psalmes. London: John Daye, 1584. Saint John’s Rare Books.

The Holie Bible faithfully translated into English, out of the authentical Latin, Diligently conferred with the Hebrew, Greeke, and other editions in divers languages. Douai: Laurence Kellam, 1609-1610. Arca Artium Rare Book Collection.

Thomas Sternhold, et al. The Whole Booke of Psalmes. London: Robert Young, 1633. Bound with the Book of Common Prayer; A Briefe Concordance or Table to the Bible of the Last Translation; and: The Way to True Happinesse … (all dated 1633). HMML Special Collections.

The Holy Bible : Contayning the Old and New Testaments, newly translated out of ye originall tongues, and with ye former translations diligently compared and revised. London (?): John Field, 1657. https://w3id.org/vhmml/readingRoom/view/534330

The Holy Bible, Containing the Bookes of the Old & New Testament. Cambridge: John Field, 1660. Arca Artium Rare Book Collection.

The Holy Bible, containing the Old Testament and the New, newly translated out of the original tongues, and with the former translations diligently compared and revised. London: Henry Hills and John Field, 1660. Saint John’s Rare Books. https://w3id.org/vhmml/readingRoom/view/519072

Bibles, French (by date)

Le premier volume de la Bible en francois ; Le second volume de la Bible en francoys. Paris: [Pierre II Regnault], 1544-1546. Arca Artium Rare Book Collection.

La Bible, qui est toute la Saincte Escriture du Vieil & du Nouueau Testament: Autrement l’anciene & la nouuelle alliance. Geneva, 1588. Saint John’s Rare Books.

Les Pseaumes de David mis en rime françoise. Sedan: Jean Jannon, 1623. Arca Artium Rare Book Collection.

Bibles, German (by date)

[Bible in German], fragment. Nuremberg: Anton Koberger, 1483. Arca Artium Art Collection.

[Bible in German], fragment. Strasbourg: Johann Grüninger, 1485. Arca Artium Art Collection.

Bibell, Alle Bücher alts und news Testaments, translated by Johann Dietenberger. Cologne: Gerwin Calenius and the heirs of Johan Quentel, 1572. Saint John’s Rare Books. https://w3id.org/vhmml/readingRoom/view/519069

Biblia, das ist, Die gantze heilige Schrifft deutsch, translated by Martin Luther. Wittenberg: August Boreck, 1626. Arca Artium Rare Book Collection.

Bibles, Greek (by date)

Hē kainē diathēkē. Paris: Simon de Colines, 1534]. Arca Artium Rare Book Collection.

Tēs Kainēs Diathēkēs hapanta; Nouum Testamentum: ex Bibliotheca Regia. Paris: Robert Estienne, 1546. Arca Artium Rare Book Collection.

Tēs Kainēs Diathēkēs hapanta. Euangelion kata Matthaion. Kata Markon. Kata Loukan. Kata Iōannēn. Praxeis tōn Apostolōn.; Nouum Iesu Christi D.N. Testamentum. Paris: Robert Estienne, 1550. Arca Artium Rare Book Collection.

Bibles, Italian

Il Nuovo ed eterno Testamento di Giesu Christo. Lyons: Jean de Tournes and Guillaume Gazeau, 1556. Arca Artium Rare Book Collection.

Bibles, Latin (by date)

A. Edward Newton. A Noble Fragment: Being a Leaf of the Gutenberg Bible, 1450-1455. New York: Gabriel Wells, 1921. College of Saint Benedict Rare Books.

Psalterium Benedictinum, fragment Mainz: Johann Fust and Peter Schoeffer, 1459. Arca Artium Art Collection.

Biblia Latina [with the Glossa Ordinaria]. Strasbourg: Adolph Rusch for Anton Koberger, 1481. Arca Artium Rare Book Collection.

Biblia Integra. Basel: Johann Froben, 1491. Arca Artium Rare Book Collection.

Biblia cum concordantijs Veteris et Noui Testamenti et sacrorum canonum: summa cum diligentia reuisa correcta et emendata. Venice: Lucantonio Giunta, [15 October 1519]. Saint John’s Rare Books.

In hoc libello contenta Psalterium Dauidicum cum aliquot canticis ecclesiasticis, litanie, hymni ecclesiastici. Paris: C. Chevallon, 1536. Arca Artium Rare Book Collection. https://w3id.org/vhmml/readingRoom/view/534504

Biblia Sacra vtrivsqve Testamenti, et Vetvs qvidem post omnes omnivm hactenus aeditiones : opera D. Sebast. Mvnsteri euulgatum, & ad Hebraicam ueritatem quoad fieri potuit redditum. Zurich: Christoph Froschauer, 1539. Saint John’s Rare Books.

Biblia Sacra ad optima quaeque veteris, ut vocant, tralationis exemplaria summa diligentia, parique fide castigata. Lyons: Jean de Tournes, 1558. Arca Artium Rare Book Collection.

Biblia Sacra Vvlgatae editionis. Rome: Ex typographia Vaticana, 1598. Arca Artium Rare Book Collection.

Bibles, Slavonic

Biblīa sirēch knigy vetkhago i novago zavĕta po i͡azykū slovenskū. Ostroh (Ukraine): Ivan Fyodorov, 1581. Arca Artium Rare Book Collection. https://w3id.org/vhmml/readingRoom/view/520945

Bibles, Syriac

Ktābā d-ʼEwangeliyon qadíšā d-Māran w-ʼAlāhan Yešúʻ Mšíḥā: Liber sacrosancti evangelii de Iesv Christo Domino & Deo nostro. Vienna: Michael Cymermannus, 1555. Arca Artium Rare Book Collection. https://w3id.org/vhmml/readingRoom/view/520958

III. Other Printed Works in this Exhibition

Théodore de Bèze. Les vrais povrtraits des hommes illvstres en piete et doctrine. [Geneva]: Jean de Laon, 1581. Arca Artium Rare Book Collection. https://w3id.org/vhmml/readingRoom/view/520948

Jean Calvin. Commentarii in Isaiam prophetam. Geneva: Jean Crispin, 1559. Saint John’s Rare Books.

Johann Ludwig Lindhammer. Der von dem H. Evangelisten Luca beschriebenen Apostel-Geschichte ausführliche Erklärung und Anwendung. Halle: Waisenhaus, 1725. Saint John’s Rare Books.

Martin Luther. Colloquia, oder Tischreden Doctor Martini Lutheri. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Schmid and Sigmund Feyerabend, 1569. Saint John’s Rare Books.

Martin Luther. Tomus primus [-quartus et idem ultimus] omnium operum. Jena: Christian Rödinger, 1556-1570. Saint John’s Rare Books.

Mordecai Nathan. Sefer ya’ir nativ : Concordantiarum Hebraicarum capita. Basel: Heinrich Petri, 1556. Saint John’s Rare Books.

Nicholas of Lyra. Postillae perpetuae in Vetus et Novus Testamentum, vol. 3 Rome: Conrad Sweynheim and Arnold Pannartz, 1470. Arca Artium Rare Book Collection.

Ordnung des Herren Nachtmal: so man die Messz nennet, sampt der Tauff vnd Insegung der Ee. [Strasbourg: Johannes Schwan], 1525. Saint John’s Rare Books. https://w3id.org/vhmml/readingRoom/view/520756

Claude Paradin and Bernard Salomon. Quadrins historiques de la Bible. Lyons: Jean de Tournes, 1553. Arca Artium Rare Book Collection. https://w3id.org/vhmml/readingRoom/view/534297

Thomas Aquinas. Diui Thome Aquinatis continuum in librum ewangelij secundum Mattheum. Venice: Andreas de Asula and Thomas de Alexandria, 1486. Saint John’s Rare Books.

Thomas Aquinas. Catena aurea. Rome: Conrad Sweynheim and Arnold Pannartz, 1470. Fragment. Arca Artium Rare Book Collection.