Mediterranean Travel

Mediterranean Travel: People, Places, Encounters

People, Places, Encounters

Mediterranean Travel: People, Places, Encounters explores themes of travel in the medieval and early modern Mediterranean. The exhibition begins with a look at maritime travel and technology, then turns to aspects of Christian and Islamic pilgrimage. Warfare and diplomacy are treated as topics of travel, given the movement of military forces and diplomats, as well as the exchange of letters and information. The exhibition includes travelers's reflections and records of their journeys, such as the legendary travels of Alexander the Great and Marco Polo that captured the minds of readers.

Mediterranean Geography

Apollonius Rhodius. L'Argonautica di Apollonio Rodio tradotta, ed illustrata. Translated by Cardinal Lodovico Flangini.

Rome: Venanzio Monaldini and Paolo Giunchi, 1791-1794.

Poetic descriptions of the voyages of ancient heroes offered listeners and readers mnemonic devices to learn about the geography of the Mediterranean.

Homer's Odyssey created the classical model for narrating epic journeys that allowed the audience to mentally map the Mediterranean through the hero's travels while they listened to the poem. Apollonius Rhodius' Argonautica (3rd century BCE), the story of Jason and the Argonauts, continued Homer's tradition of mapping travels through heroic action. The poem provided an introduction to Mediterranean places and peoples, whether fantastic and real. Cardinal Lodovico Flangini's translation includes an engraved map of the Argonauts' journey, allowing the reader to chart the text against a physical map emblematic of the emerging discipline of early modern historical criticism.

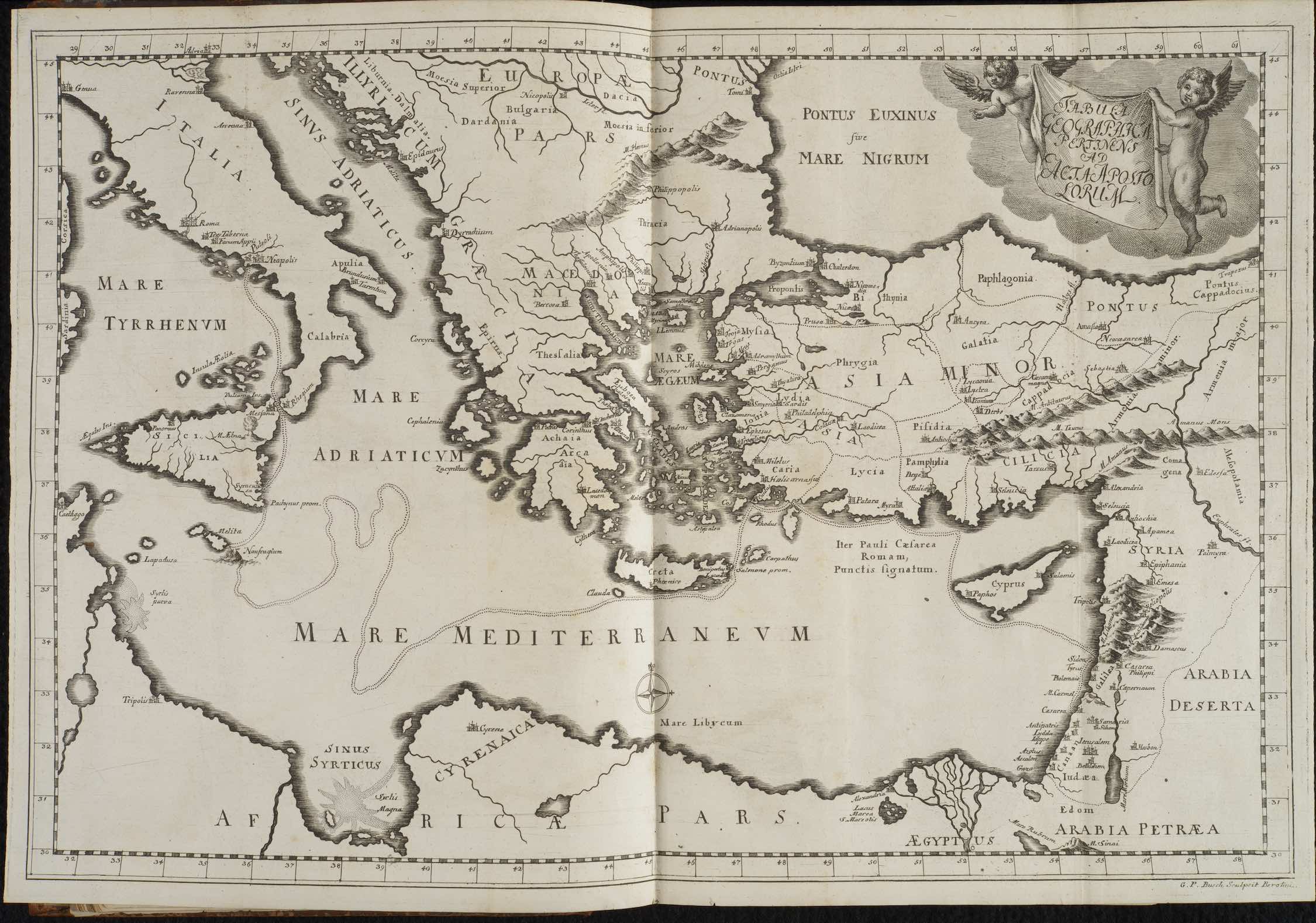

Johann Ludwig Lindhammer. Der von dem h. Evangelisten Luca beschriebenen Apostelgeschichte ausführliche Erklärung und Anwendung.

Halle: Waisenhaus, 1725.

The Apostles' travels in the Mediterranean followed similar paths as ancient heroes since both depended on the natural harbors and cities to facilitate travel over long distances.

Commentaries on the Acts of the Apostles gathered greater interest in the 18th-century. The narrative quality of the text provided opportunities for scholars to place Christianity in a historical context to counter Enlightenment attacks the faith's historicity. Using the new methods of historical criticism, scholars such as Lindhammer mapped the Apostle Paul's journey just as scholars of Rome and Greece mapped Homer, Vergil, and Apollonius Rhodius. As a result, early modern intellectuals began to see the Mediterranean as a place that inherently cultivated long-standing traditions rather than experiencing rapid change due to its geography.

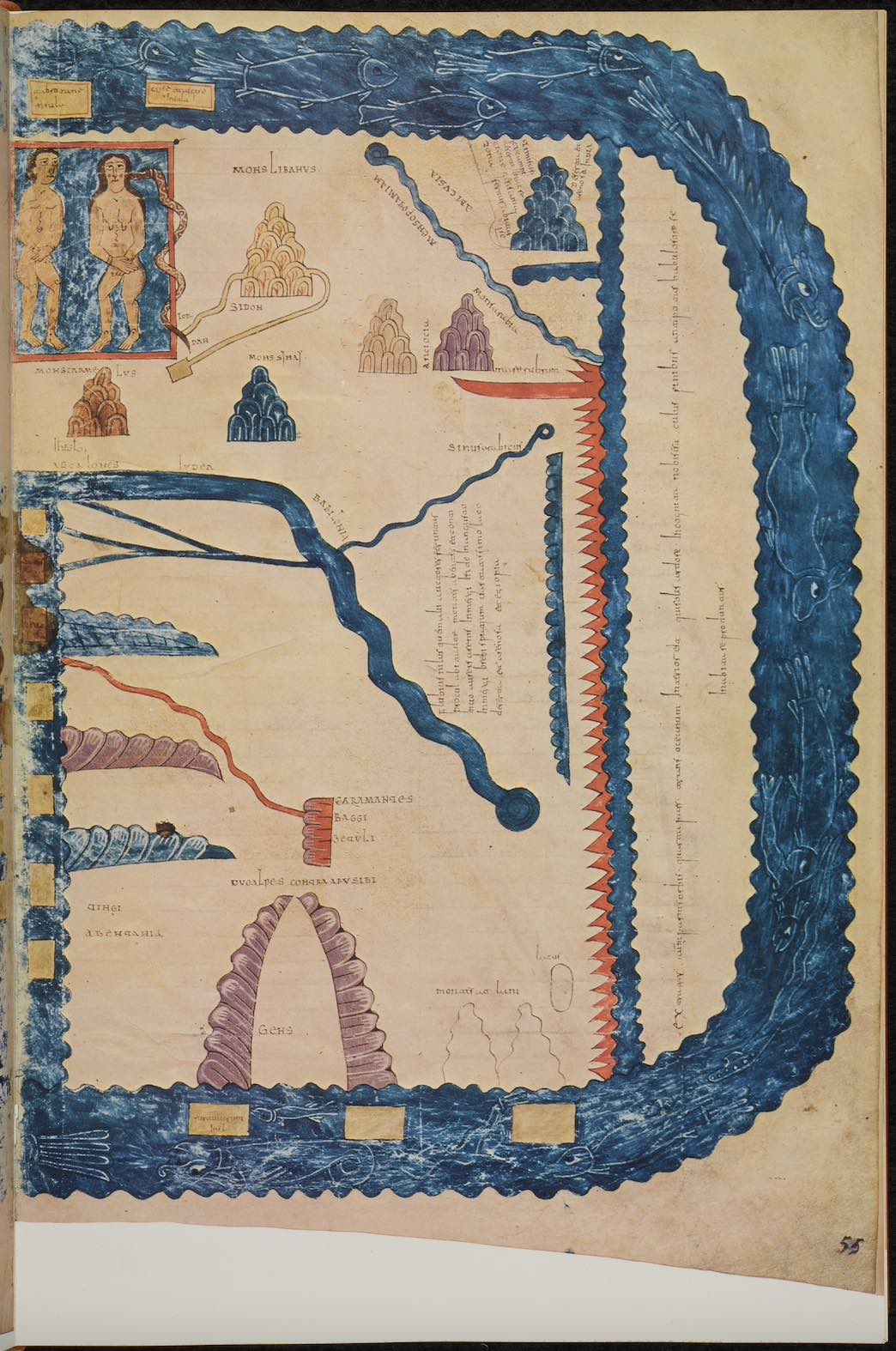

Beatus of Liébana. Commentarium in Apocalipsin libri duodecim.

Spain, 976 CE

Medieval maps served as conduits for Greek and Roman geography to the early modern world, while reimagining the Mediterranean Sea according to their reading of the Bible.

Early medieval writers, such as Beatus of Liébana, used non-classical sources to study Mediterranean geography in addition to the works of Ptolemy and Strabo. The Bible and patristic writers like Orosius, Isidore of Seville and Eusebius included geographic information framed within the framework of God's creation and time. This combination allowed Beatus of Liébana's 8th-century Commentary on the Apocalypse to reconceptualiz the Mediterranean as both a physical place to travel and a spiritual geography mapping God's providence through the journeys of the Apostles and conversion of the Roman Empire to Christianity.

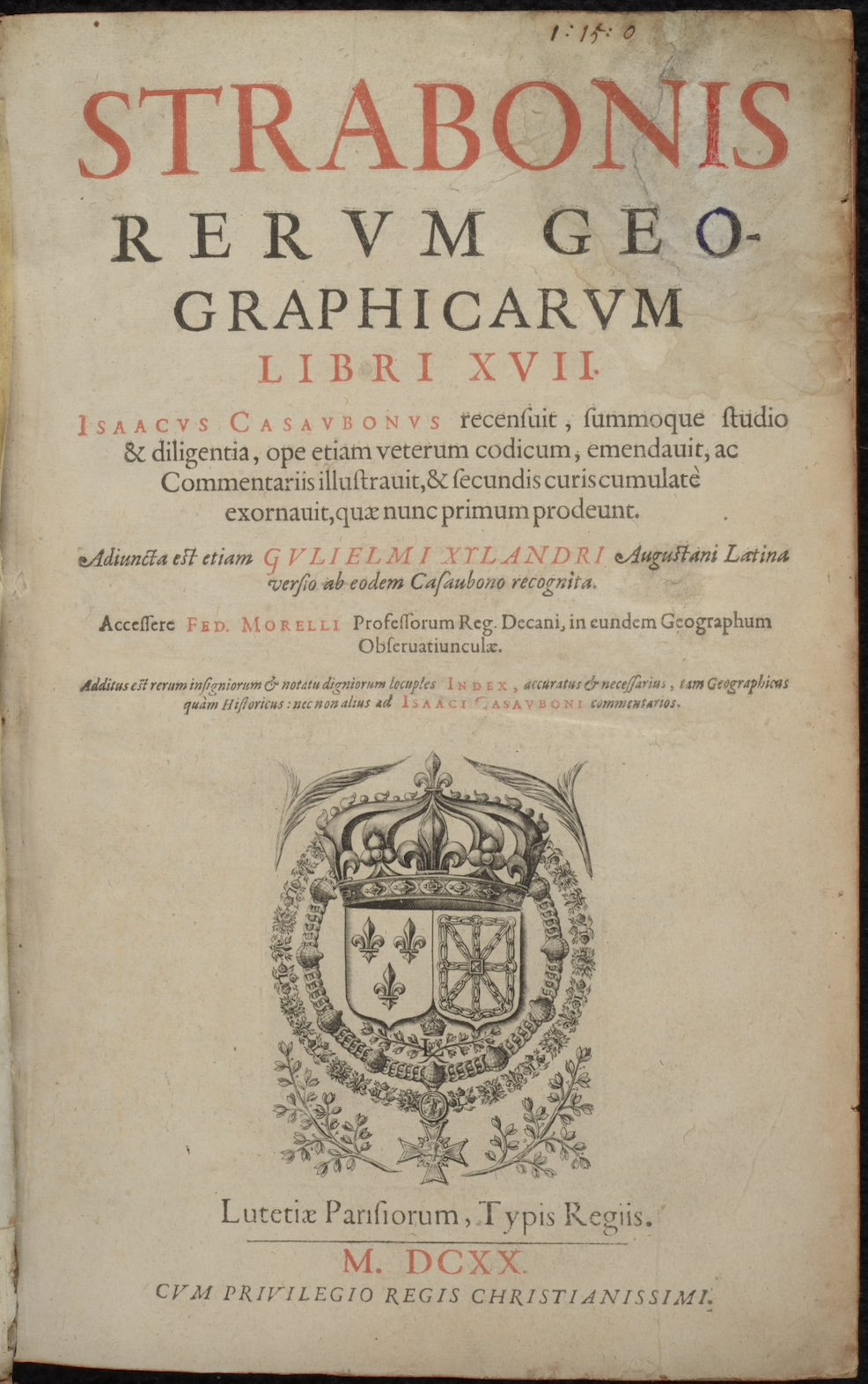

Strabo. Strabonis rerum geographicarum libri XVII.

Paris: Typis Regiis, 1620.

The Greek and Roman tradition of combining history and geography preserved the geographic knowledge of the ancient Mediterranean into the early modern era.

Strabo's Geographica became the standard encyclopedia of geographic knowledge of the classical world and would remain the foundation for studying geography through the early 16th century. Composed in 17 books between 20 BCE and 23 CE, Strabo described the nature of geography as a subject that included both political geography and physical geography drawing on the vast corpus of Greek and Roman writers. Strabo detailed the known geography of the world in his day centered on the Mediterranean and connected regions; a study facilitated by the unification of the Mediterranean Sea under the Roman Emperor Augustus Caesar.

War and Embassies

Naval Actions of the Order of the Knights of Malta.

Malta or France, 18th century

Threats to trade and the danger of raiding created international alliances to patrol the Mediterranean, as dominance of shipping lanes secured spheres of influence and wealth.

The Algerian vessel called Half Moon captured in the waters of Alicante by the Order of Malta's vessel Santa Caterina, which was commanded by Fra' Adrien de Langon under the orders of Lieutenant General Jean-François de Chevestre-Cintray, 12 April 1713. Though based in Malta, the Order of Malta's navy patrolled the Mediterranean to stop piracy and carry out military actions against the Ottoman Turks. The Knights' port of Valletta served as a neutral harbor to European Christian powers that supported the Order's defense of Christendom against the Turks.

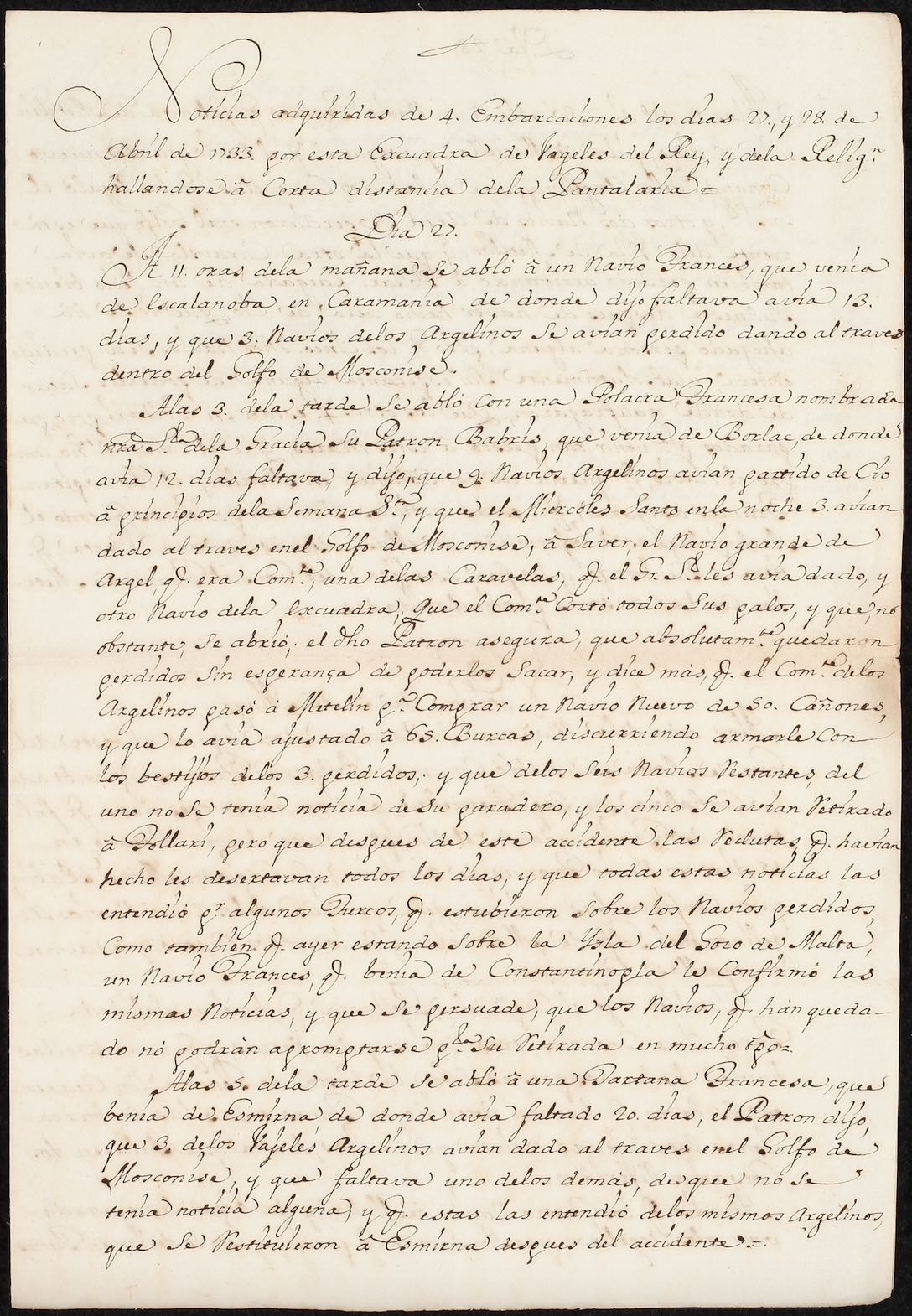

Noticias adquiridas de 4. embarcaciones los dias 27., y 28. de Abril de 1733.

Mediterranean Sea, 1733 April 27-28

Seizing ports and strategic locations in the Mediterranean, like Oran in Algeria, provided Western European and the Ottomans with bases to control trade and extend influence.

Dispatch describing the naval actions of the Spanish royal squadron commanded by Blas de Lezo y Olavarrieta alongside ships from the Order of the Knights of Malta off the coast of Tunisia in April 1733. The joint operation was undertaken to protect the Spanish controlled presidio of Oran from a rumored attack by an Ottoman fleet. Coordinating with the Knights of Malta, Lezo y Olavarrieta records how the squadron stopped several trading vessels between Tunisia and Malta to enquire about the Ottoman's fleet before taking safe harbor in Valletta.

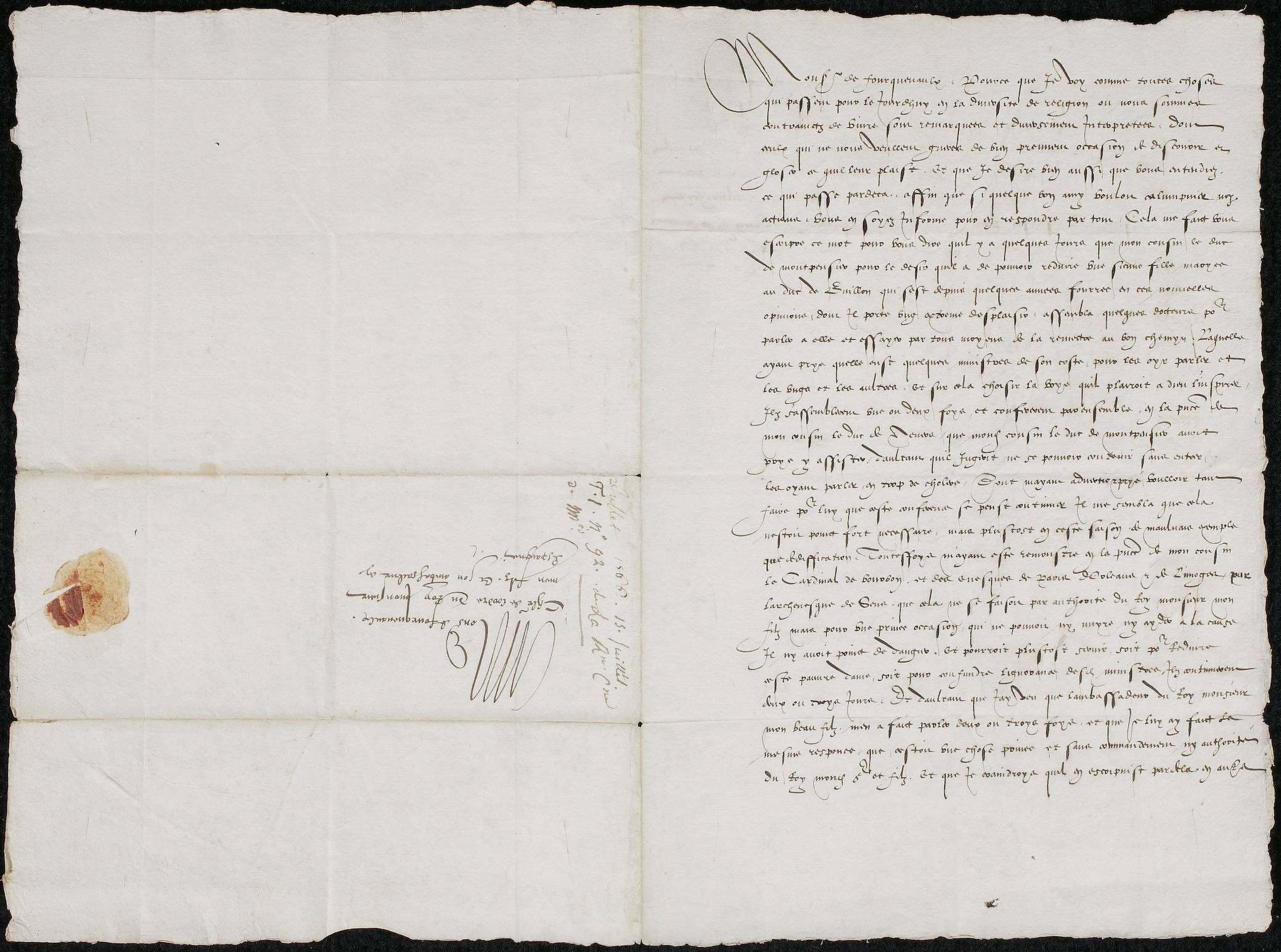

Letter from Catherine de Medici to M. de Fourquevaux, Ambassador to the Spanish Court.

Paris, 1566 July 15

Ambassadors provided kingdoms with the ability to maintain contact with their allies and rivals, creating an extension of the kingdom into foreign realms.

Ambassadors offered monarchs the ability to maintain contact in foreign lands with their home country without risking travel to conduct diplomacy. Permanent embassies shortened the distance between nations, allowing negotiations to take place in a more regular manner. They also served as conduits of information to the court. Catherine de Medici's letter sought intelligence from Monsieur de Fourquevaux concerning those in the Spanish court who criticized the French king's attitude towards Huguenots during the French Wars of Religion, while also discussing the need to frustrate the prospective marriage between the daughter of the Duke of Monpensier (a Catholic) to the Duke of Bouillon (a Huguenot).

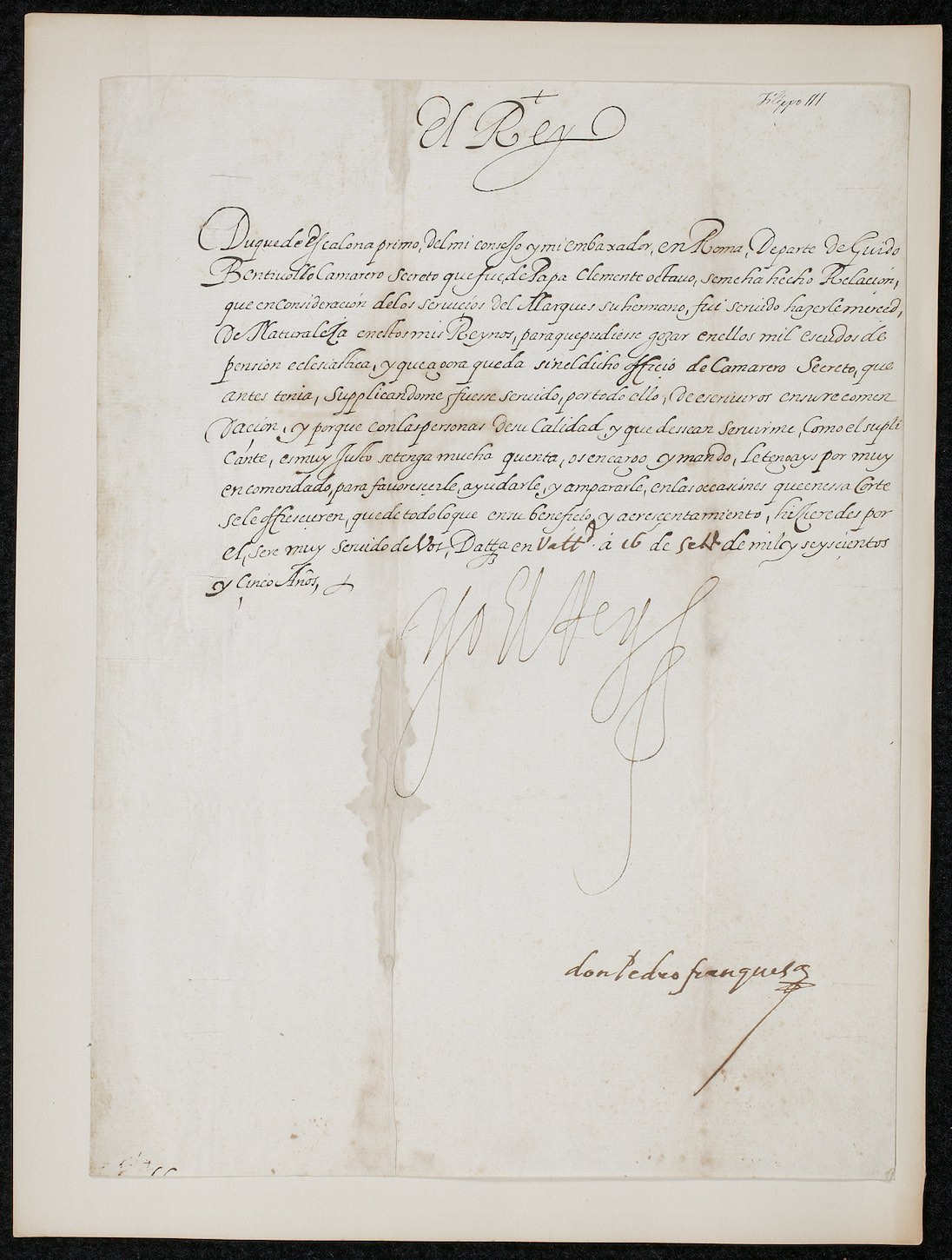

Letter of Phillip III, King of Spain, to Juan Gaspar Fernández Pacheco, Duque de Escalona and Ambassador to Rome.

Valladolid, 1605 September 16

Solidifying alliances during times of war often involved the creation of political networks tied to the crown.

King Phillip III grants Spanish nationality and a pension of one thousand escudos to the future Cardinal Guido Bentivoglio d'Aragona, member of the secret chamber of Pope Clement VIII. Philip III granted Bentivoglio the merced for his service on behalf of Guido's brother Ippolito Bentivoglio d'Aragona, Marchese di Gualteri, who supported the Spanish favorite Duke Cesare d'Este of Modena against the papacy over the rights of the Duchy of Ferrera after the death of Duke Alfonso II d'Este in 1597.

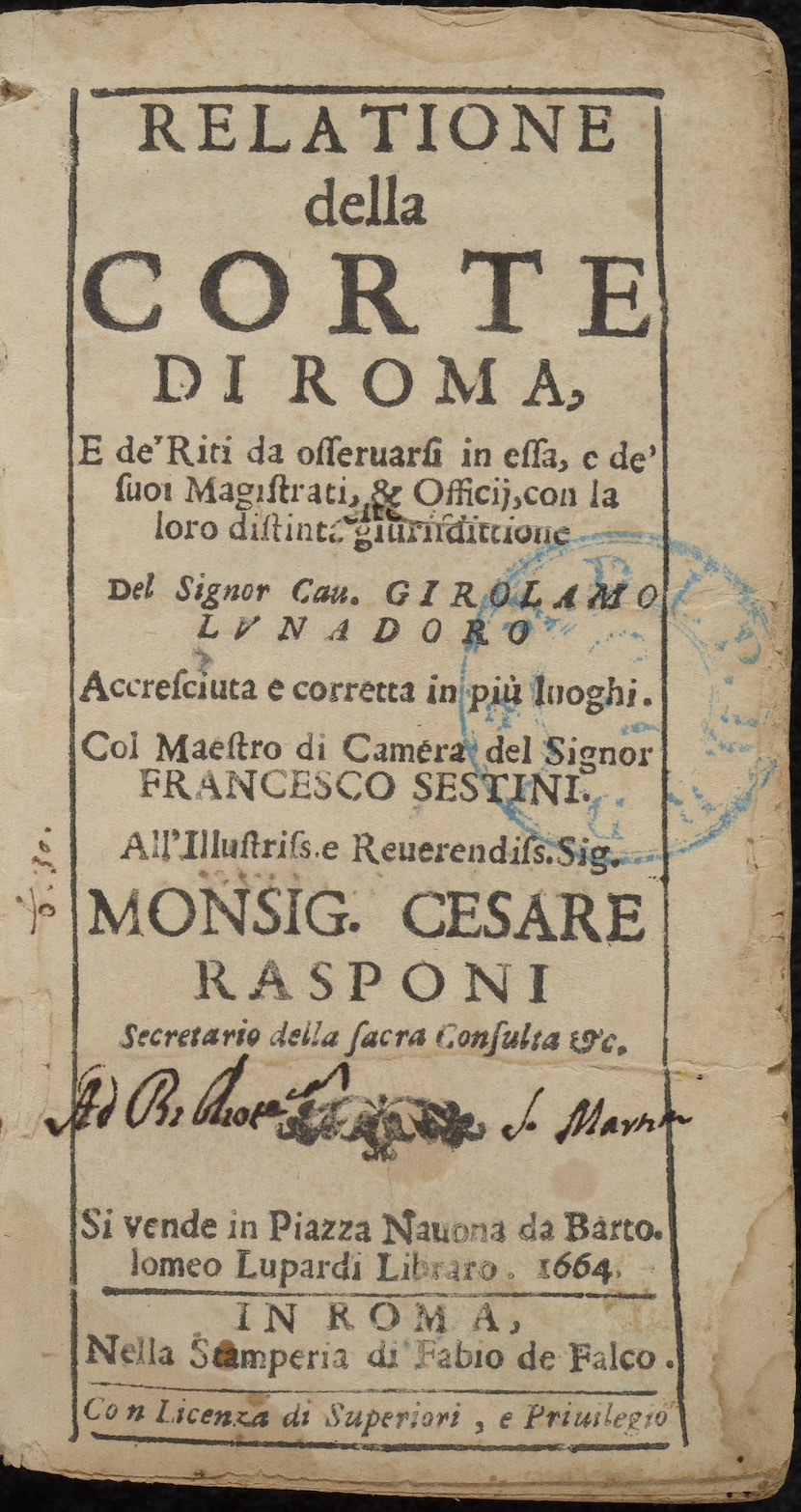

Girolamo Lunadoro. Relatione della corte di Roma, e de' riti da osseruarsi in essa, e de' suoi magistrati, & officii, con la loro distinta giurisdittione. Revised and corrected by Francesco Sestini.

Rome: Fabio de Falco, 1664.

Manuals describing the function of courts and their corresponding offices and officials provided invaluable information for a foreign emissary engaging in diplomacy.

Navigating foreign courts proved essential for the success of emissaries traveling to seek favor or conduct business in foreign courts. To improve success, early modern writers like Girolamo Lunadoro composed manuals detailing the operation of the distinct bodies of the papal curia to navigate the complex bureaucracy of Rome. By the 18th century, printers produced almanacs of past and current officials to facilitate the composition of letters and legal documents between parties, such as the lists of officials found in the annual royal publication Guía del estado eclesiástico seglar y regular.

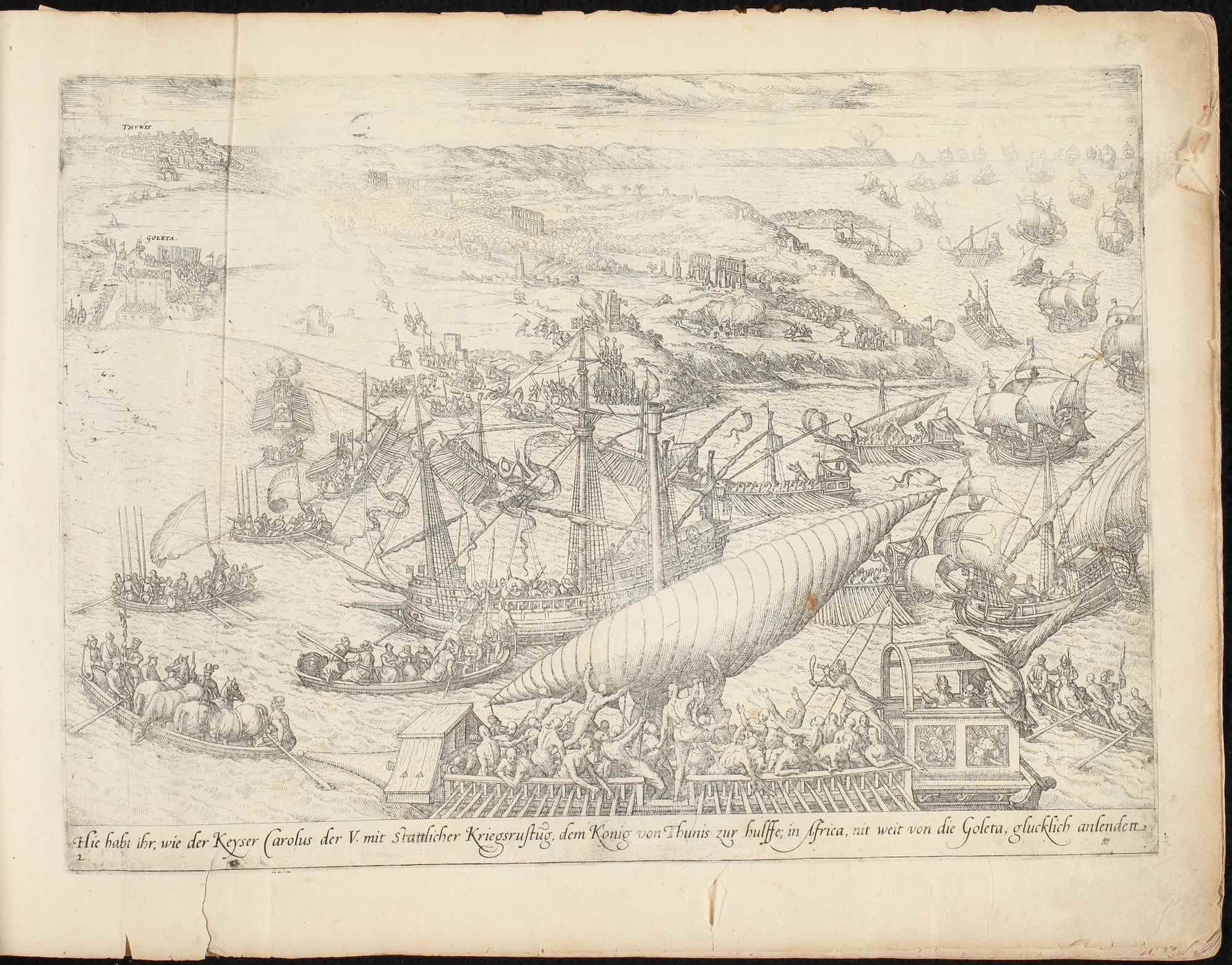

Kurtze Erzeichniss wie Keyser Carolus der V. in Africa dem Konig von Thunis, so von dem Barbarossen vertrieben, mit Kriegsrustung zur Hulffe komt, vnd was sich zugedragn, kont ihr in diese folgende Figurn fein ordentlich nach ein ander sehen … geschach im Iar nach Christi Gebuertt M.D.XXXV.

Cologne (?): Frans Hogenberg, 1570s-1580s (?)

Large scale invasions in the 16th century brought tens of thousands of Europeans into contact with North African peoples. Africans captured in war were often sold into slavery and transported to Europe or the Americas.

Emperor Charles V's invasion of Tunisia in 1535 responded to the increasing threat of Ottoman pirates in the central Mediterranean, who raided Christian littoral communities and threatened the European trading networks. The invasion combined Spanish, Italian, Maltese, and Austrian forces against Turkish and North African naval and land forces. The internationalization of war for the control of the Mediterranean increased the movements of peoples, whether through naval and land forces, or the resulting slave trade and migrations the accompanied such conflicts.

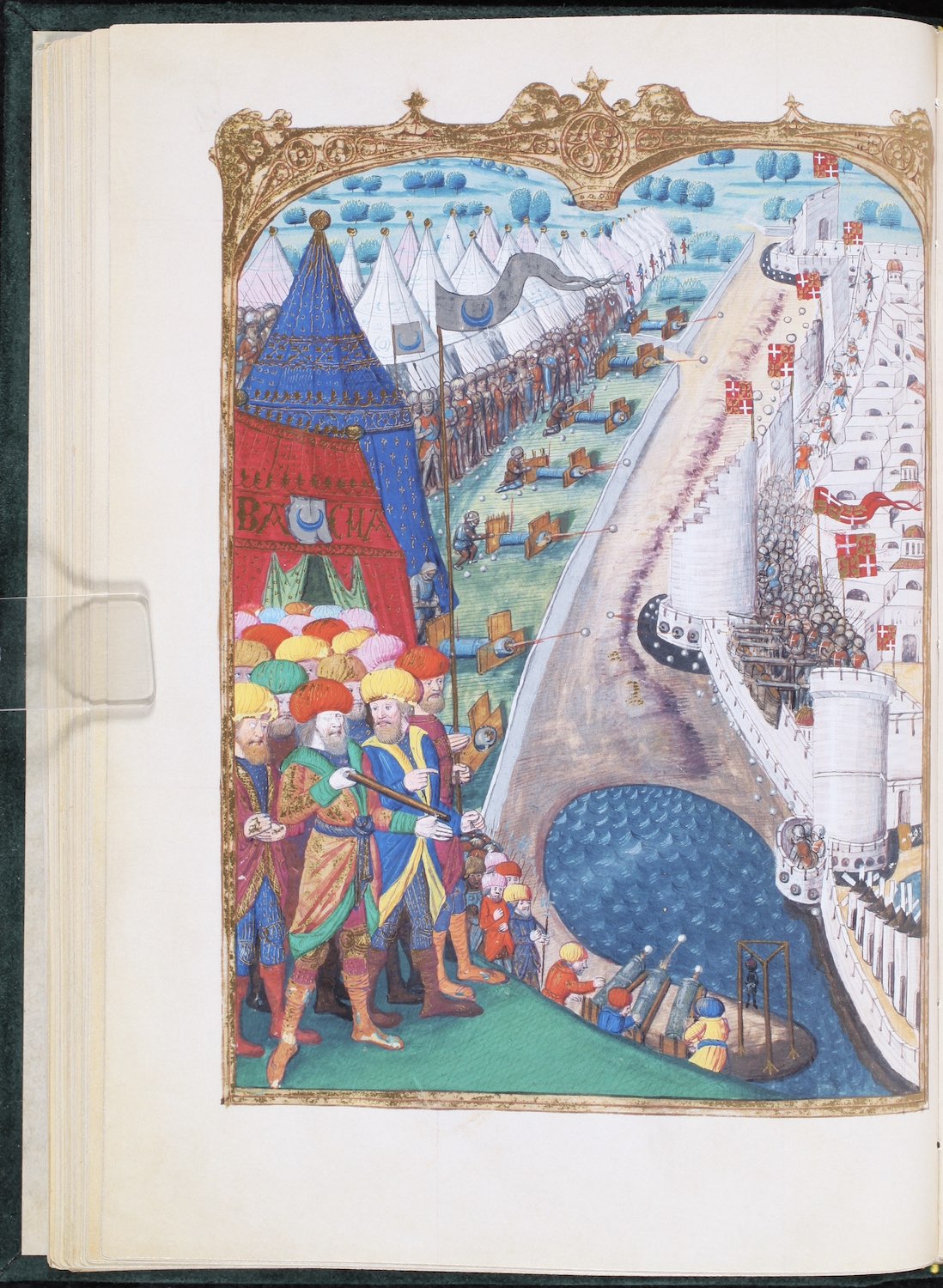

Guillaume Caoursin. Obsidionis Rhodiae urbis descriptio.

France, 1481-1500

Struggles over the Mediterranean brought diverse peoples into conflict, often with the result of exchanging science, technology, and tactics.

Mehmed II besieged Rhodes in 1480 to remove the military outpost controlled by the Order of Saint John of Jerusalem (later also known as the Order of Malta) that threatened sea trade and communication routes between Ottoman territories in Turkey and Egypt. Rhodes was also one of the last remaining Christian military outposts in the Eastern Mediterranean, inhibiting Ottoman expansion to the West. Though adversaries, the Knights of the Order of Saint John and the Ottomans employed similar technologies developed from shared contacts and trading partners in the Mediterranean, showing that the Mediterranean encounter centered on conflict often involved the exchange of science and technology.

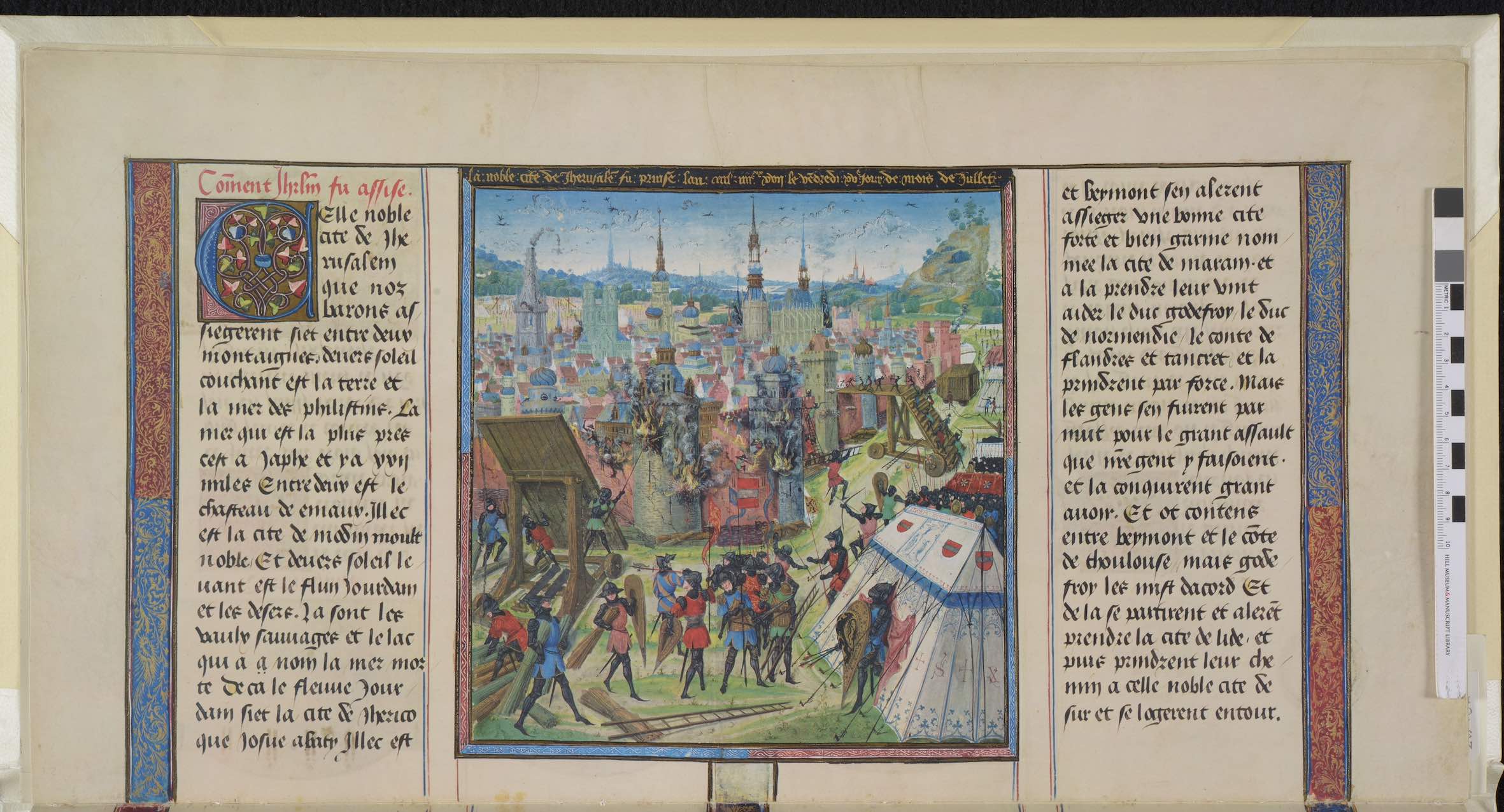

Chroniques de Jérusalem abrégées.

Flanders, 15th century

The First Crusade remained a popular subject among readers of Latin Europe, who reimagined the military conflict and encounters with Muslims within the milieu of their own times.

Bishop William of Tyre's 12th-century history of the Crusading Kingdoms known as the Historia rerum in partibus transmarinis gestarum was unique among crusading narratives since William had grown up in Jerusalem rather than arriving as part of a crusade originating in Europe. Although his narrative history retained the crusading conceit of the conquest of Jerusalem in 1099, he also presented the military encounters between Muslims and Christians less as a result of divine will, and more often within the context of political rivalries. The 15th-century abridged and highly illuminated French version produced in the court of Duke Philip III of Burgundy lost William's nuanced understanding of the Crusade, and instead portrayed the conflict within the context of chivalry and combat found in the late medieval court.

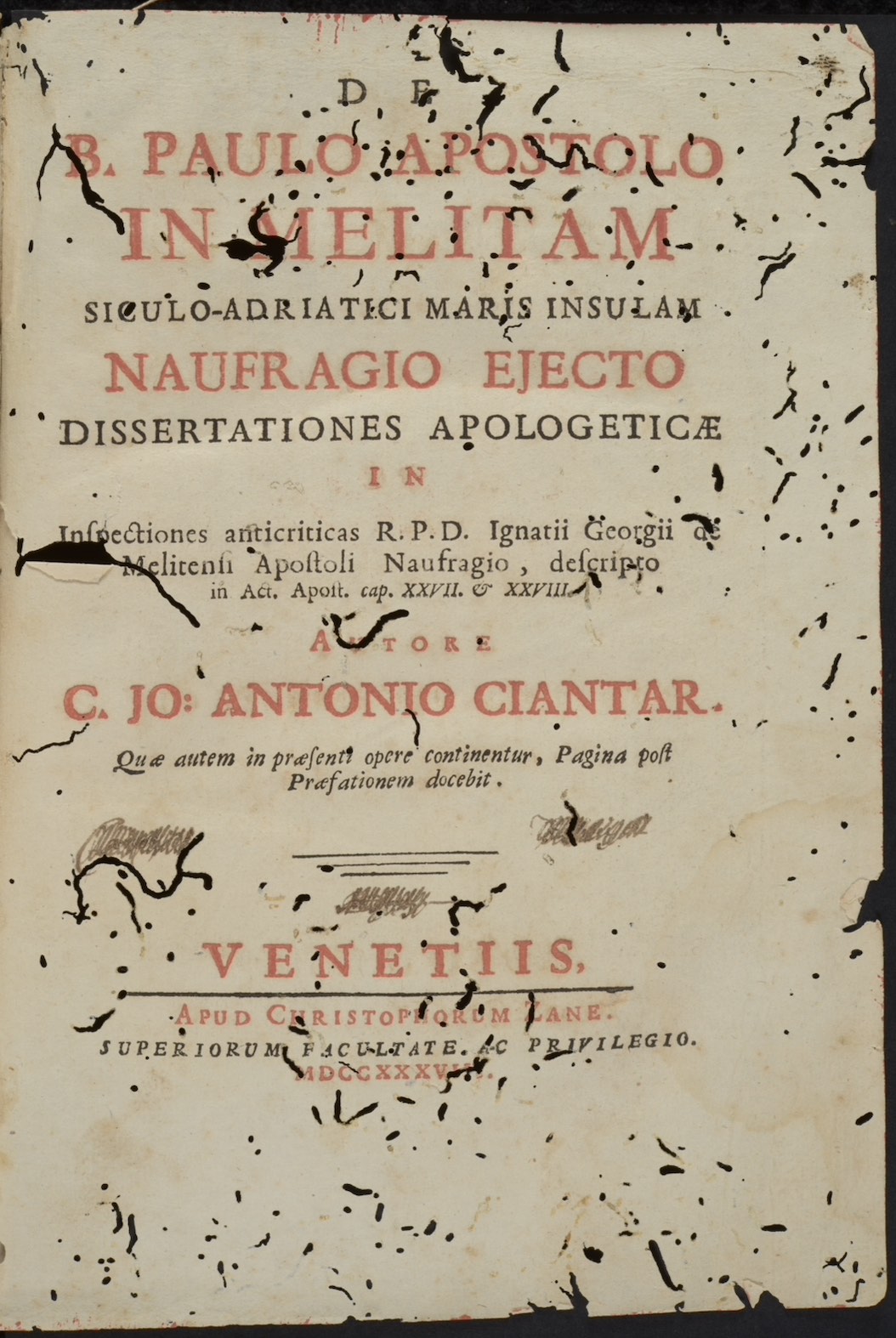

Pilgrimage

Giovanni Antonio Ciantar. De B. Paulo Apostolo in Melitam siculo-adriatici maris insulam naufragio ejecto dissertationes apologeticae in inspectiones anticriticas r.p.d. Ignatii Georgii de Melitensi Apostoli naufragio, descripto in Act. Apost. cap. XXVII. & XXVIII.

Venice: Cristophorum Zane, 1738.

Defending the authenticity of a pilgrimage site helped secure local communities that depended on the economy of pilgrimage, as well as the donations that could flow to support the shrine.

Giovanni Antonio Ciantar defended Malta as the location of Paul's shipwreck as described in Acts 28.1 against Ignjat Đurđević, who argued that Paul landed on the island Mljet in the Adriatic Sea. Ciantar's point-by-point rebuttal to support of Malta as the place of Paul's landing and subsequent miracles performed by the saint. Ciantar also remarked on the sale of shark's teeth as pilgrimage souvenirs. Maltese jewelers employed shark's teeth as relics to sell to pilgrims, stating that they were the tongues of serpents turned to stone by the apostle. These glossopetrae (tongue stones) were thought to have magical qualities, and as a result became a lucrative jewelry item sold to pilgrims and sailors coming to the island.

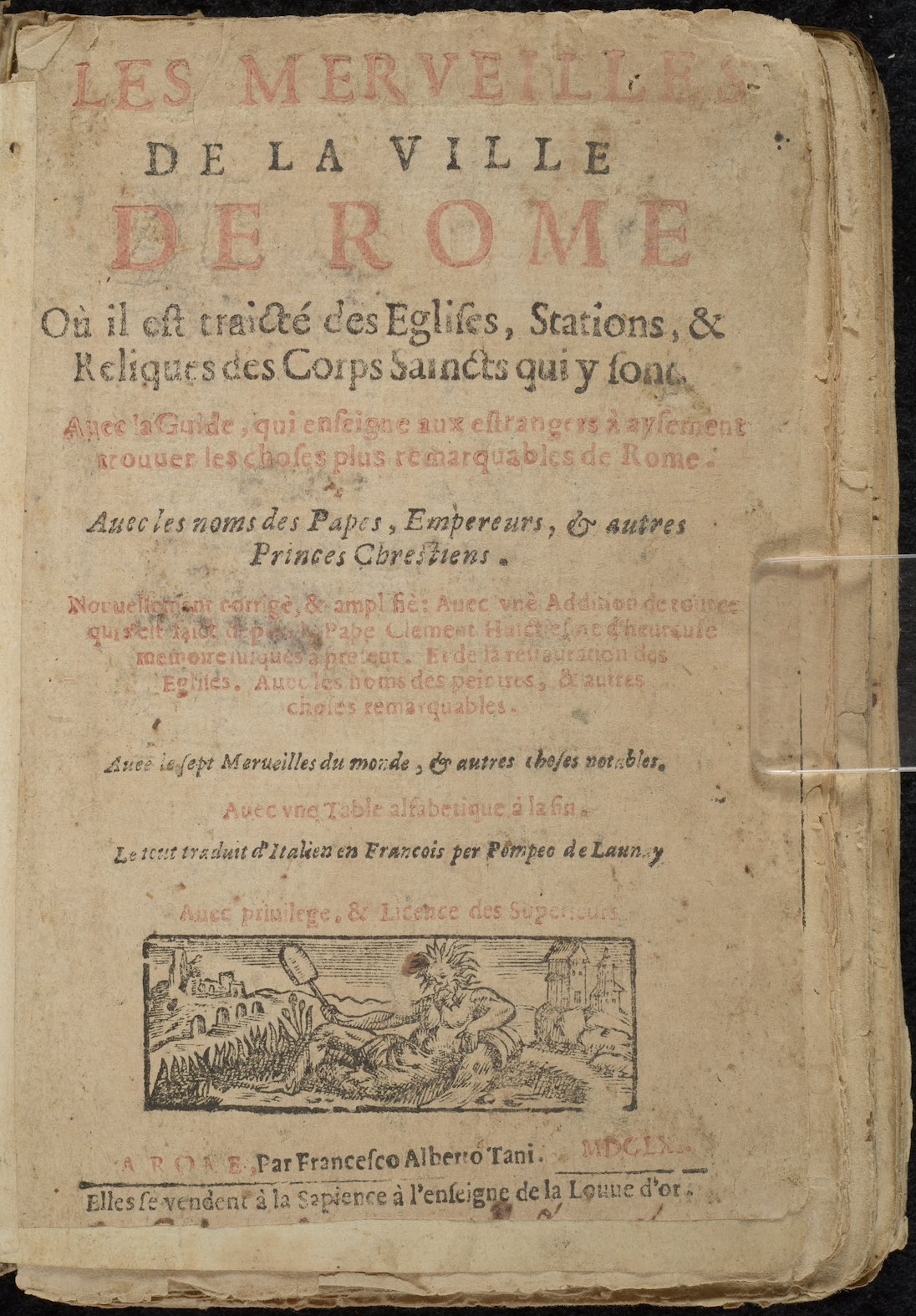

Girolamo Francini and Andrea Palladio. Les merveilles de la ville de Rome: où il est traicté des eglises, stations, & reliques des corps saincts qui y sont : auec la guide, qui enseigne aux estrangers à aysement trouuer les choses plus remarquables de Rome : auec les noms des papes, empereurs, & autres princes Chrestiens.

Rome: Francesco Alberto Tani, 1661.

Medieval pilgrims to Rome, much like those to Jerusalem, left behind a rich tradition for early modern writers and printers to develop detailed pilgrimage guides to understand the city.

The 12th-century Mirabilia urbis Romae or Wonders of the City of Rome described the seven major churches of Rome, remarking on relics particular to certain churches as well as the Roman ruins that dominated the city. What began as a medieval guide to the city developed into a genre of pilgrimage guidebook. Early modern writers built on the medieval tradition of illustrated manuscripts of the Mirabilia urbis Romae by incorporating woodcuts to illustrate the text, as seen in the edition by Girolamo Francini and Andrea Palladio. Translated into French, Francini's and Palladio's edition also used recent studies of Rome to augment the original text to differentiate their publication from other guidebooks printed in the city.

Fioravante Martinelli. Roma ricercata nel suo sito, con tutte le curiosità, che in esso si ritrovano tanto antiche, come moderne.

Rome: Michelangelo Barbiellini, 1769.

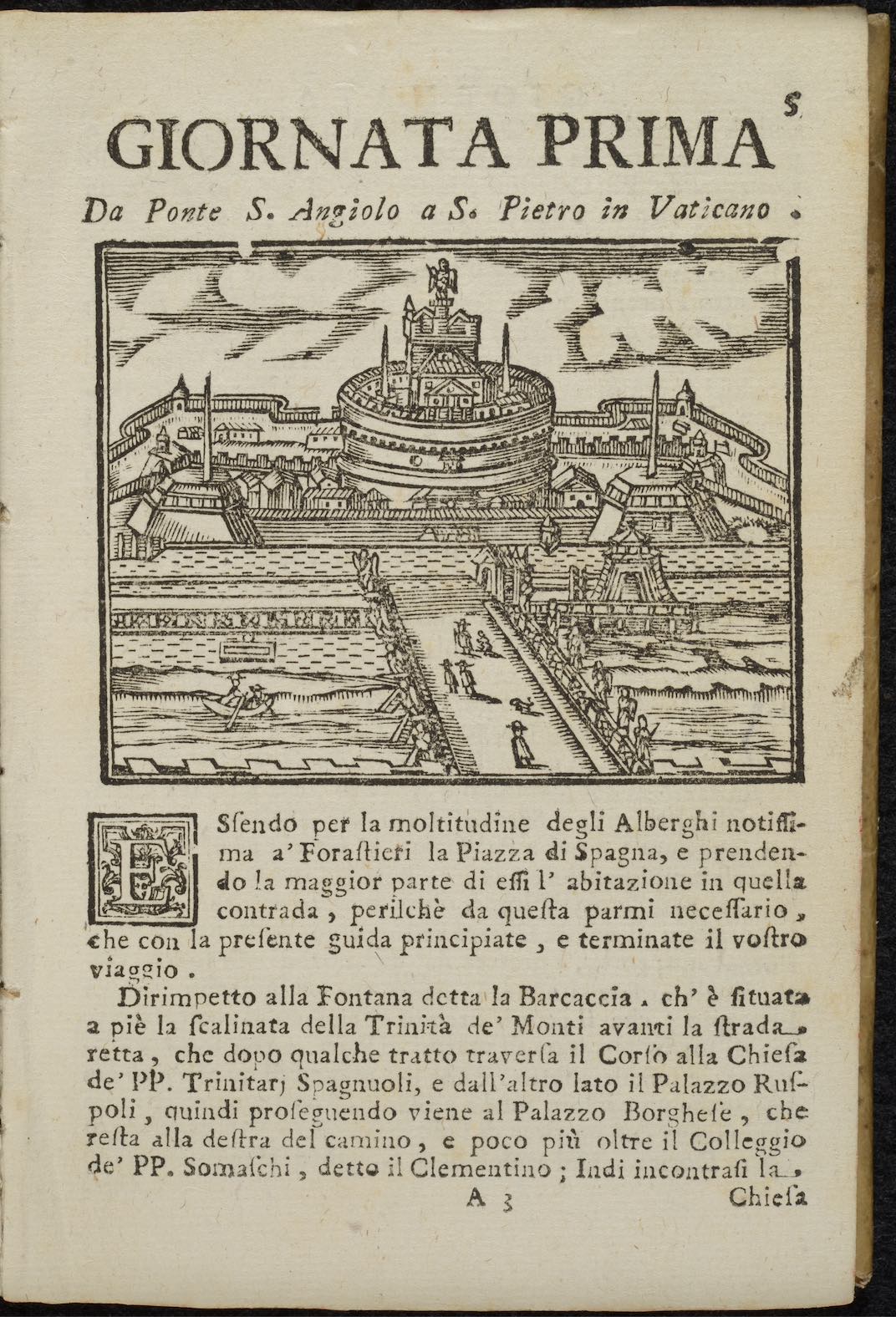

Early modern pilgrims to Rome found a multitude of guidebooks to aid the travel, including those that provided a structured visit over a series of days based on the principal churches of the city.

Fioravante Martinelli's Roma ricercata nel suo sito, first published in 1650, provided early modern pilgrims to Rome with a day-to-day guide that foreshadowed modern guidebooks designed to balance the numerous sites to visit in Rome with those who could only afford to stay for a few days. Though structured around visiting the major churches, Martinelli's book offered insights into the smaller things one should notice when visiting churches, such as particular relics in monastic communities. The success of Martinelli's guidebook led to its adoption by foreign emissaries traveling to Rome, who purchased the book alongside Girolamo Lunadoro's Relatione della corte di Roma; the standard guide to understanding the bureaucracy of the papal curia.

Giacomo Lauro. Roma vetus et noua : aedificia eius praecipua suisquaeque locis.

Rome: Andrea Frei, 1625.

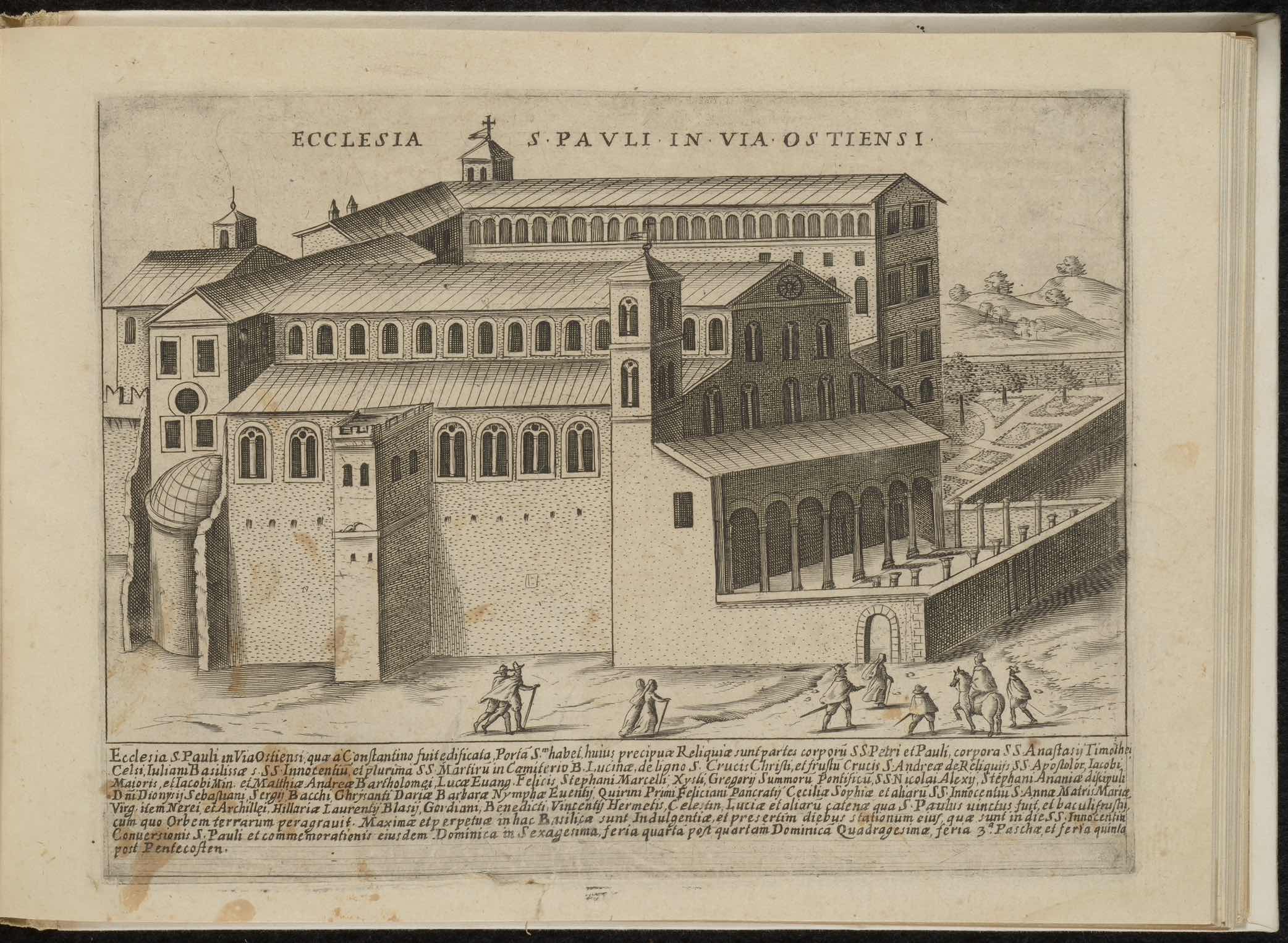

Printers, writers, and engravers took advantage of the many nationalities that travelled to pilgrimage sites to increase profit and promote the city as an attraction.

Giacomo Lauro' Roma vetus et noua, also entitled Antiquae Urbis Splendor, combined images of ancient Rome and the churches of Rome created during his prolific career as an engraver. The book saw several different editions due to the flexibility of binding the engravings according to theme to raise or lower the price. The 1625 edition stands out for its trilingual translation of the Latin text into German, Italian, and French on the verso of each page. The edition coincided with a large influx of pilgrims into the city during the Jubilee year and demonstrates how printers and booksellers tailored their publications to the market conditions they encountered.

Viaggio da Venetia al S. Sepolcro, et al Monte Sinai: co'l dissegno delle città, castelli, ville, chiese, monasterij, isole, porti, & fiumi, che sin la si ritrouano : et vna breue regola di quanto si deue osseruare nel detto viaggio e quello, che si pagha da luoco à luoco si di datij, come d'altre cose.

Venice: Domenico Louisa, 1690.

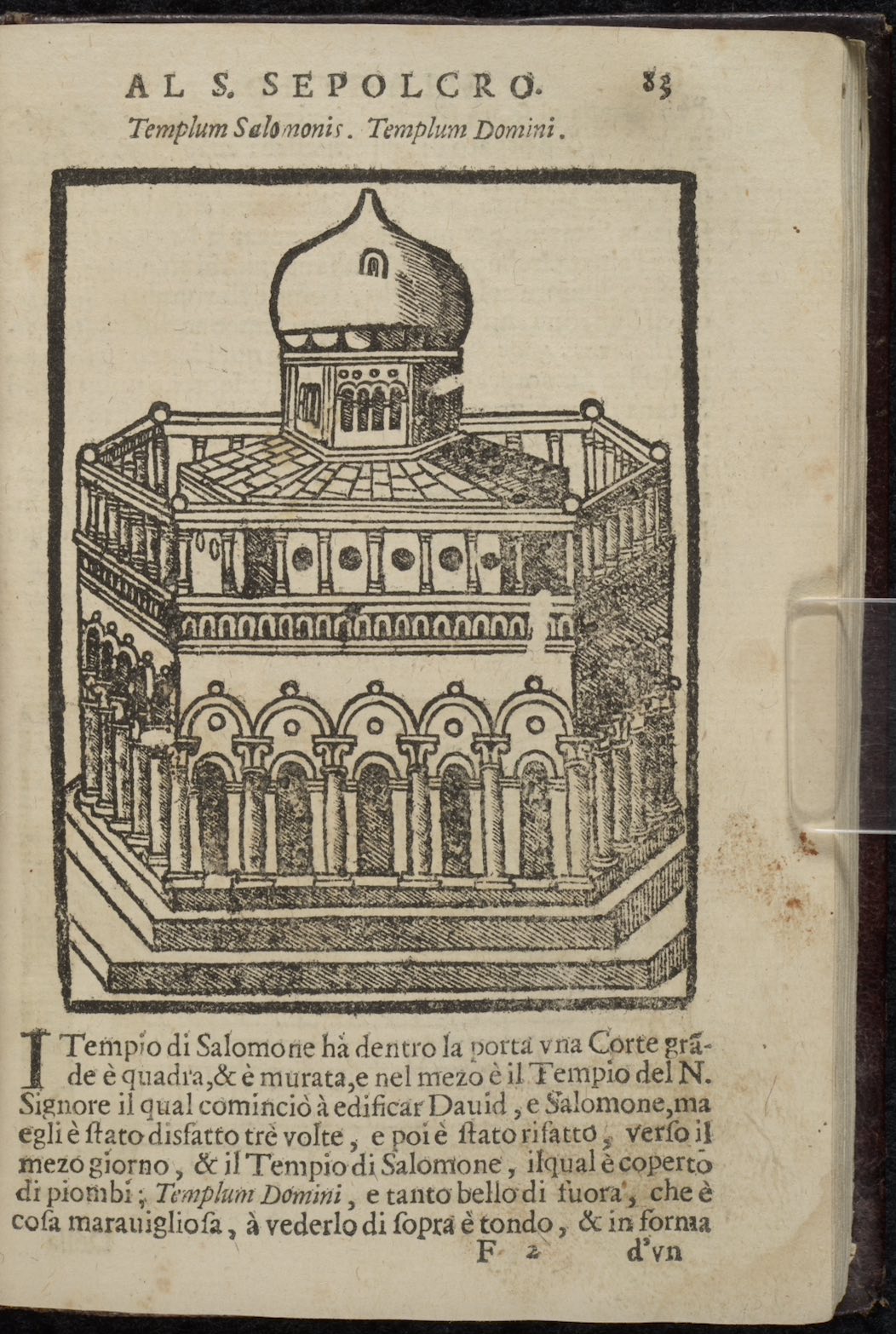

Medieval writers provided early modern pilgrims with accessible texts that mixed practical advice with legendary stories and local lore that created highly imagined encounters in the Holy Land.

The anonymous 15th-century Viaggio da Venetia al S. Sepolcro, first published in 1518 by Niccolò detto Zopino, was the most popular guidebook to the Holy Land in Italian, seeing over 60 editions by 1800. The medieval vernacular guidebooks broke with earlier traditional Latin travel accounts that emphasized text over image by providing a personalized guidebook with a highly illustrated text. It reflected the growing interest in providing visual images to support the text, even imaginary stories, so that readers and pilgrims could prepare for their journey. The emergence of the printing press and use of the woodcut allowed pilgrims to carry a personal guide with them in the small format book.

Jacques Florent Goujon. Histoire et voyage de la Terre-Sainte: où tout ce qu'il y a de plus remarquable dans les Saints lieux, est tres-exactement descrit.

Lyon: Pierre Compagnon and Robert Taillandier, 1670.

Early modern guidebooks became increasingly complex in text and image, as readers' expectations changed and writers spent more time in the Holy Land.

The Franciscan Jacques Florent Goujon spent two years in Palestine and another year and a half in Egypt and Syria working in the Franciscan Custody of the Holy Land. Goujon argued that his long stay in the Holy Land gave his guidebook an authority lacking in other books. He guidebook was organized into 33 different visits that a pilgrim could make, corresponding to the 33 years of Jesus' earthly life. Each visit is broken down into a day excursion, and included history, advice, devotional guides, maps and architectural diagrams that allowed the pilgrim to engage in pious pilgrimage as well as historical investigation.

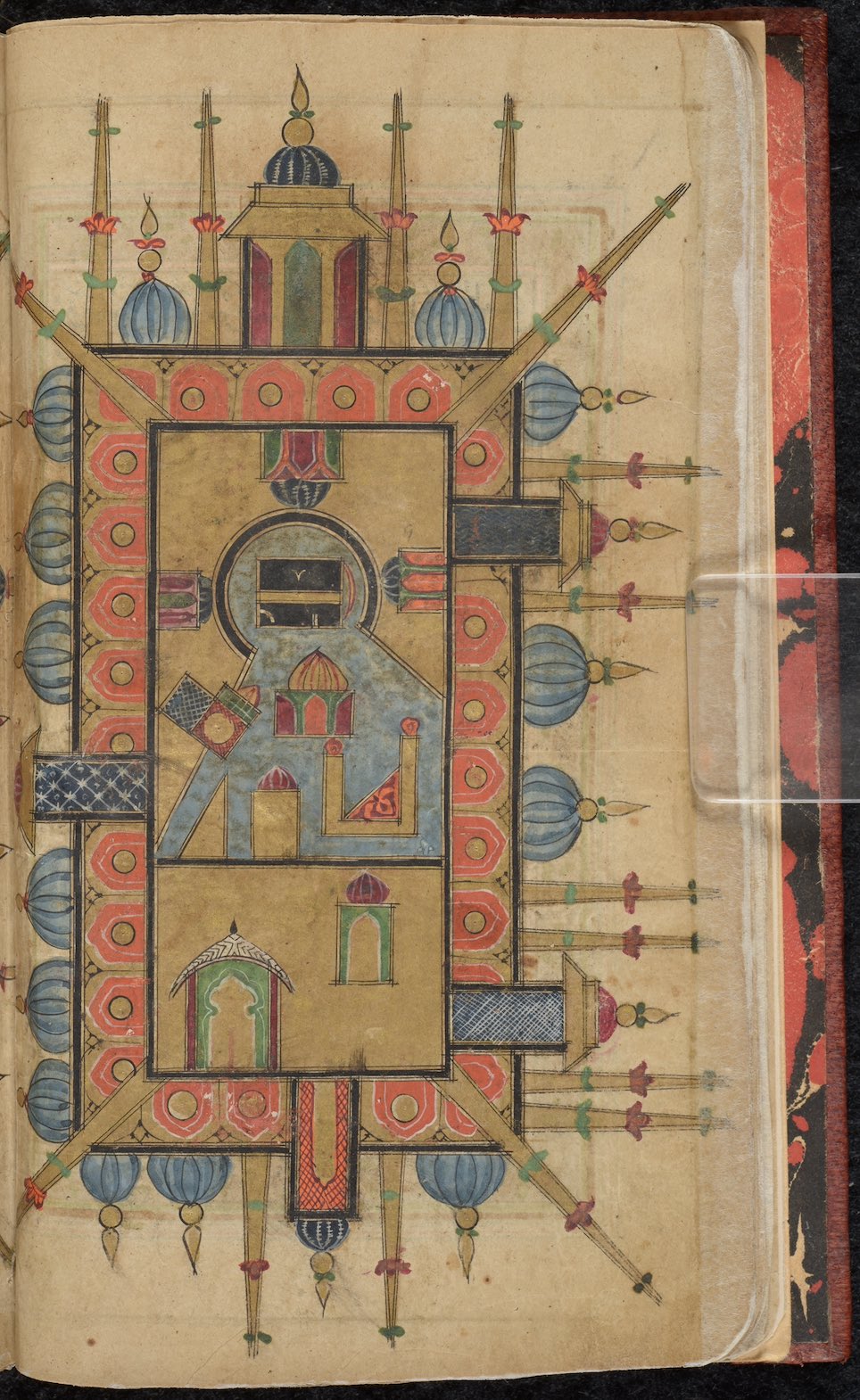

Muḥammad ibn Sulaymān al-Jazūlī. Dalā’il al-khayrāt

Kashmir, 18th century

Islamic books of prayers for the prophet Muhammad at times included illustrations of Mecca and Mdina, providing a “virtual” pilgrimage for those who had yet to make the Hajj.

This manuscript copy of Dalā’il al-khayrāt (“Tokens of blessings”) by Muḥammad ibn Sulaymān al-Jazūlī (d. 1465) was produced in northern India, an area that saw an increase in highly decorative manuscript production during the Mughal Empire. The illuminated illustration depicts two cities sacred to Islam: Mecca (right) and Medina (left). The black square with gold band shown in the center of Mecca represents the Ka‘bah, the ultimate destination of the Muslim pilgrimage, the Hajj.

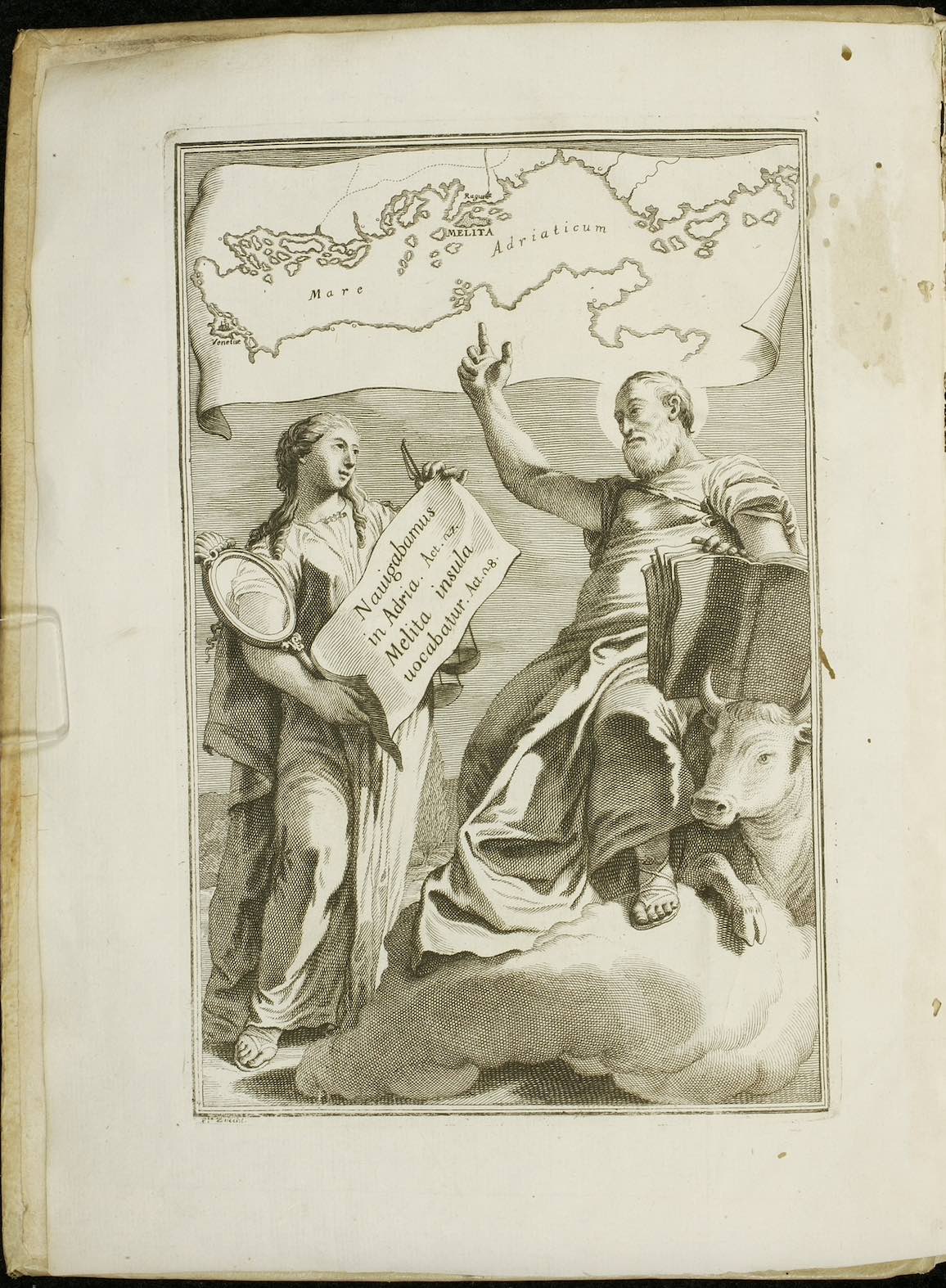

Ignjat Đurđević. D. Paulus Apostolus in Mari, Quod Nunc Venetus Sinus Dicitur, Naufragus, et Melitae Dalmatensis insulae post Naufragium Hospes sive, de genuino significatu duorum locorum in Actibus Apostolicis. Cap. XXVII. 27. Navigantibus nobis in Adria Cap. XXVIII. 1. Tunc cognovimus, quia Melita insula vocabatur. Inspectiones Anticriticae.

Venice: Cristophorum Zane, 1730.

The profit derived from pilgrimage, both spiritual in the form of penance and material via the money spent by pilgrims, offered ample opportunity to challenge the authenticity of a shrine.

The Benedictine scholar Ignjat Đurđević from Ragusa (Dubrovnik) argued that Saint Paul landed on the island Mljet in the Adriatic Sea, rather than the traditional location on the island of Malta. Both islands went by the Latin name “Melita”. The engraving here shows Saint Luke pointing to the island “Melita” off the coast of Croatia in the Adriatic Sea, an argument based on his interpretation of Acts 27.27 (navigantibus nobis in Adria), where Paul sailed before being shipwrecked on the island of “Melita” in Acts 28.1. Contesting Malta as the location of Paul's shipwreck threatened Malta as a pilgrimage center, as well as the endangering the spiritual rewards of those who had previously peregrinated to the island for the remission of sins.

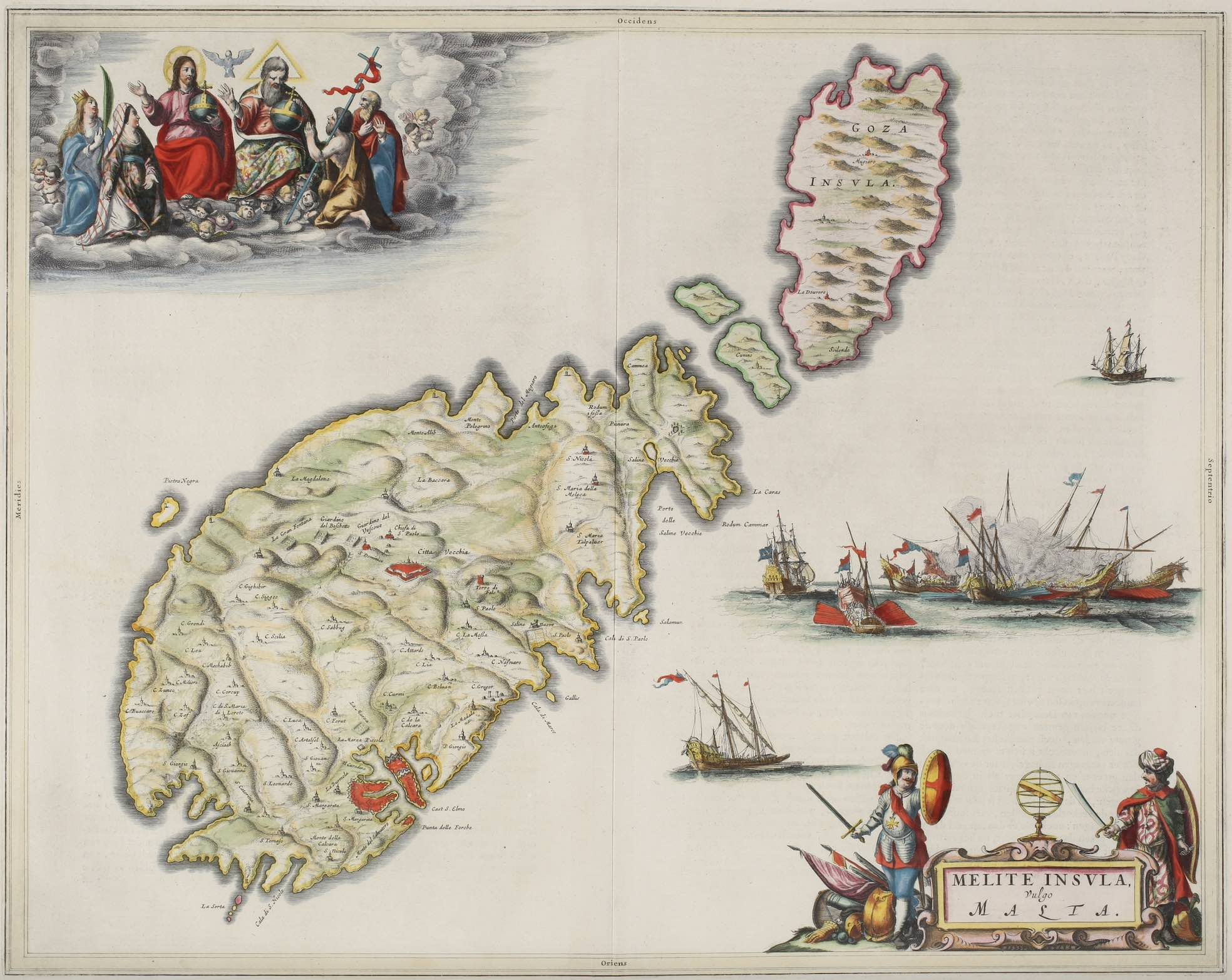

J. Blaeus grooten atlas, oft, Werelt-beschryving, in welcke 't aertryck, de zee, en hemel, wordt vertoont en beschreven

Amsterdam: Joan Blaeu, 1665.

Large scale atlases created a means by which wealthy merchants, pilgrims and voyagers could understand the topography, urbanization and the political context of a land prior to travel.

Hand-colored engraving entitled, “Melite Insvla, vulgo Malta” contains martial scenes of the fleet of the Order of Malta and an illustrated Knight and Turk in lower right corner. The illustrations show the political authority over the island and the Knights' role in the defense of Christianity; the illustration of the Trinity in upper left corner symbolizes the divine providence and Catholic faith associated with the defense of the island, especially after the defeat of the Ottoman Turks in Great Siege of 1565.

Technology and Navigation

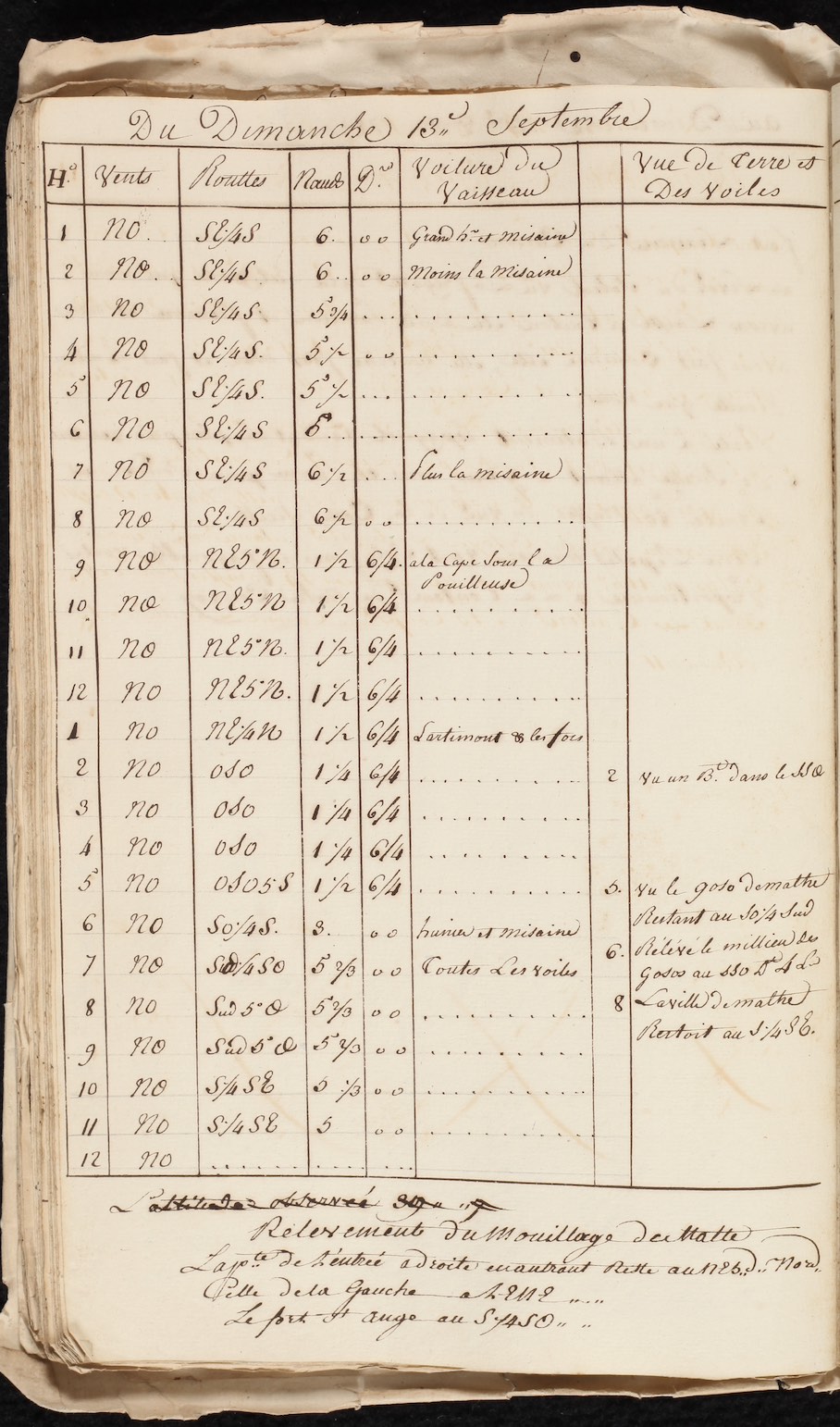

Journal dela Compagne dela fregatte L'Iris.

Mediterranean Sea, 1789 July 13 - 1790 May 12

Captains required substantial scientific and technical knowledge to navigate their vessels as seen here in the daily and hourly log of time, wind, and bearings.

The frigate L'Iris was commanded by Hercule de Ligondès-Rochefort, a knight of Malta, who also served in the French navy. The voyage began on 13 July 1789, when King Louis XVI ordered L'Iris to sail to Algeria to settle disputes between France and the Bey of Algiers over French and Algerian corsair activity. Chevalier Ligondès' lieutenant, Thomas de la Bastide de Beauregard, recorded the ship's log, including bearing, wind, fathoms, and ship sightings. Distance here is expressed in nautical miles, made by taking the square root of the observer's height in feet above sea level multiplied by 1.17. Where the observer stood on the ship, whether on the quarterdeck or forecastle, determined the calculation of the bearing based on the elevation of the deck.

![Ephraim Chambers. <em>Cyclopaedia, or, An universal dictionary of arts and sciences: containing an explication of the terms, and an account of the things signified thereby, in the several arts, both liberal and mechanical, and the several sciences, human and divine. 2 volumes</em>.<br>London: Printed for D. Midwinter, A. Bettesworth and C. Hitch ... [and 14 others], 1738.](../../../assets/img/exhibitions/mediterranean-travel-people-places-encounters/4_2_Chambers_volume_2_AE_5_C4_v_2_1738_02.jpg)

Ephraim Chambers. Cyclopaedia, or, An universal dictionary of arts and sciences: containing an explication of the terms, and an account of the things signified thereby, in the several arts, both liberal and mechanical, and the several sciences, human and divine. 2 volumes.

London: Printed for D. Midwinter, A. Bettesworth and C. Hitch ... [and 14 others], 1738.

A mariners' technical vocabulary provided a lexicon privy to those who shared the unique world of the sea as a way of life.

The increasing complexity of ship design in the 17th and 18th century coincided with the early modern interest in universal knowledge as the key to unfolding the mysteries of the world through rational study. Chamber's Cyclopaedia entry “Ship” included a detailed illustrated engraving of a 74-gun ship of the line third rate, the backbone of the French, and later British navy, in the Mediterranean. While demonstrating the technical prowess of British ship builders, the technical drawing of the ship broke down the complex terminology privy to sailors, making the knowledge accessible to all readers interested in the sea.

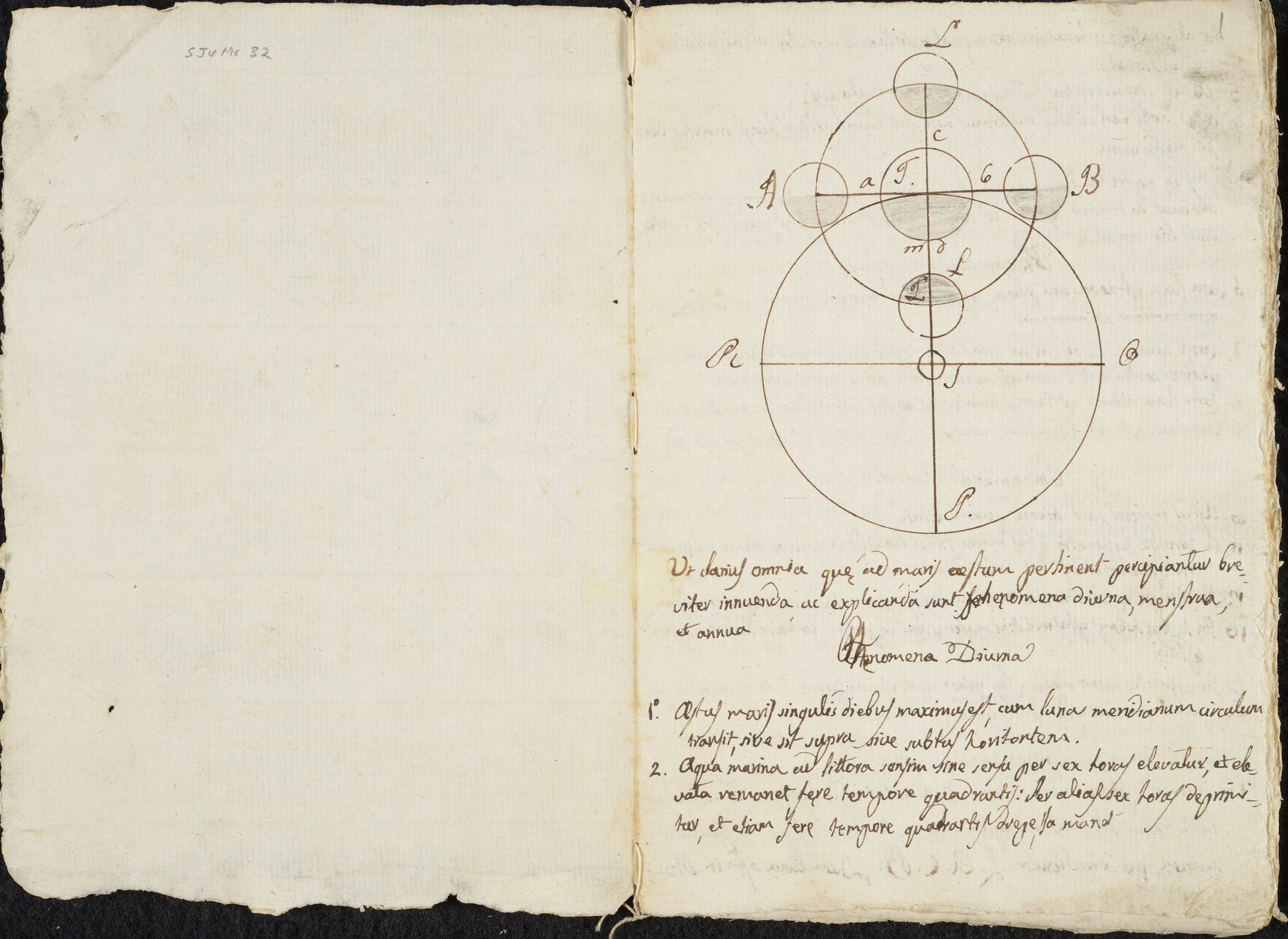

Miscellany on astronomy.

Italy, 18th century

Knowledge of tides and their relationship with the moon was essential for any captain wanting to leave or make port.

The abandonment of the geocentric Ptolemaic system and the development of optics led to a revolution in astronomy in early modern Europe. The new heliocentric system helped mariners increase their accuracy when creating star charts for navigation. Essential seafaring questions such as the calculation of tides became far more accurate, as seen in this manuscript where one can learn how to calculate the yearly, monthly, and daily cycle of tides to gauge when one could leave and arrive in shallow harbors.

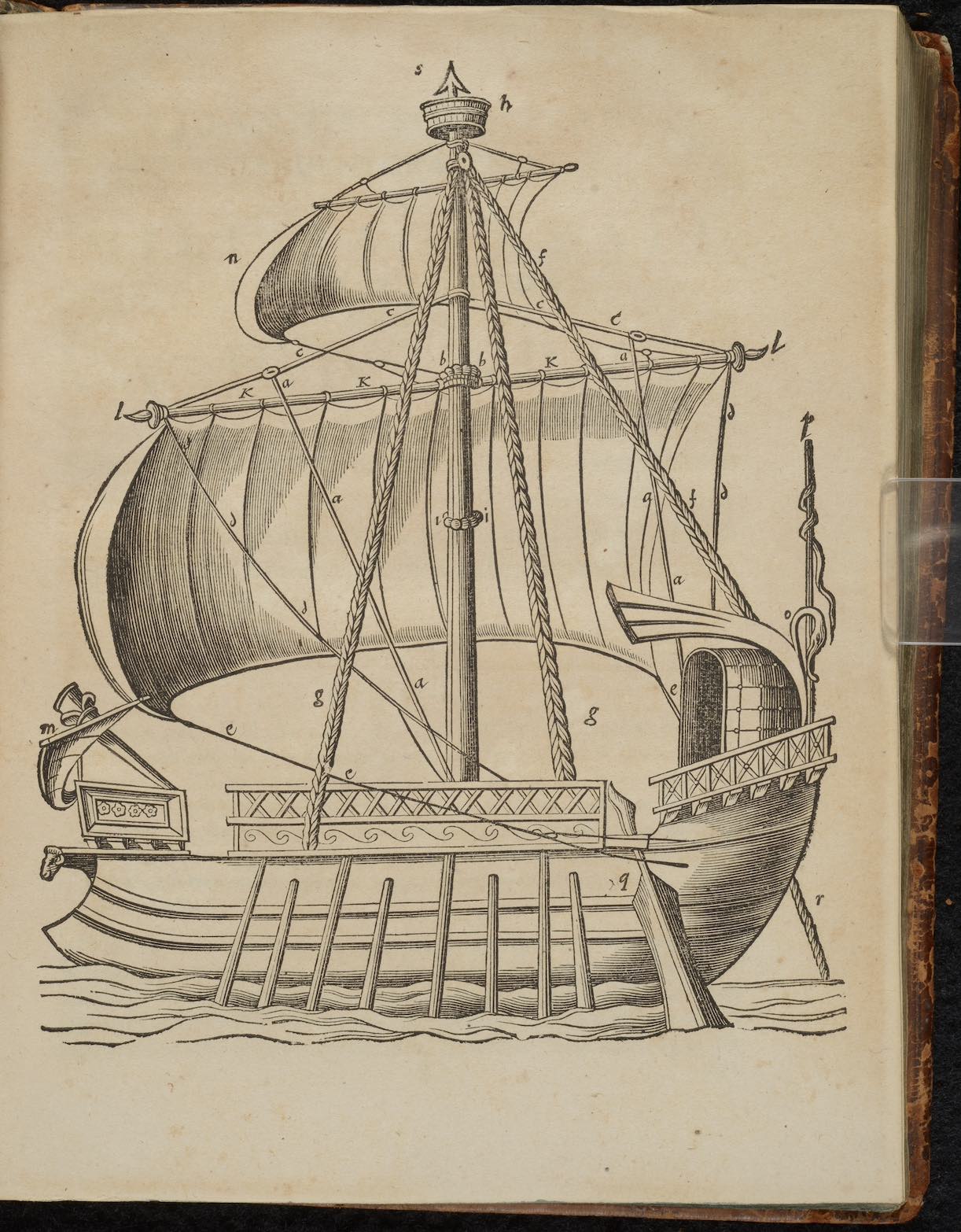

Johannes Scheffer. Joannis Schefferi Argentoratensis, De militia navali veterum libri quatuor: ad historiam graecam latinamque vtiles.

Uppsala: Jan Jansson, 1654.

The Mediterranean galley saw nearly 3000 years of military and trading history, only being replaced in the 18th century with the arrival of the frigate and ships of the line.

The ancient galley survived as a trade and military vessel through the 18th century due to its ability to move without wind and maneuver quickly using manned oars. With later refinements such as the inclusion of the lateen sail, castles and cannon, the galley retained a privileged place among pirates and pirate hunters, as slower caravels, cogs, brigantines and even galleons and carracks could be hunted from island hideouts by skilled captains seeking unsuspecting scores.

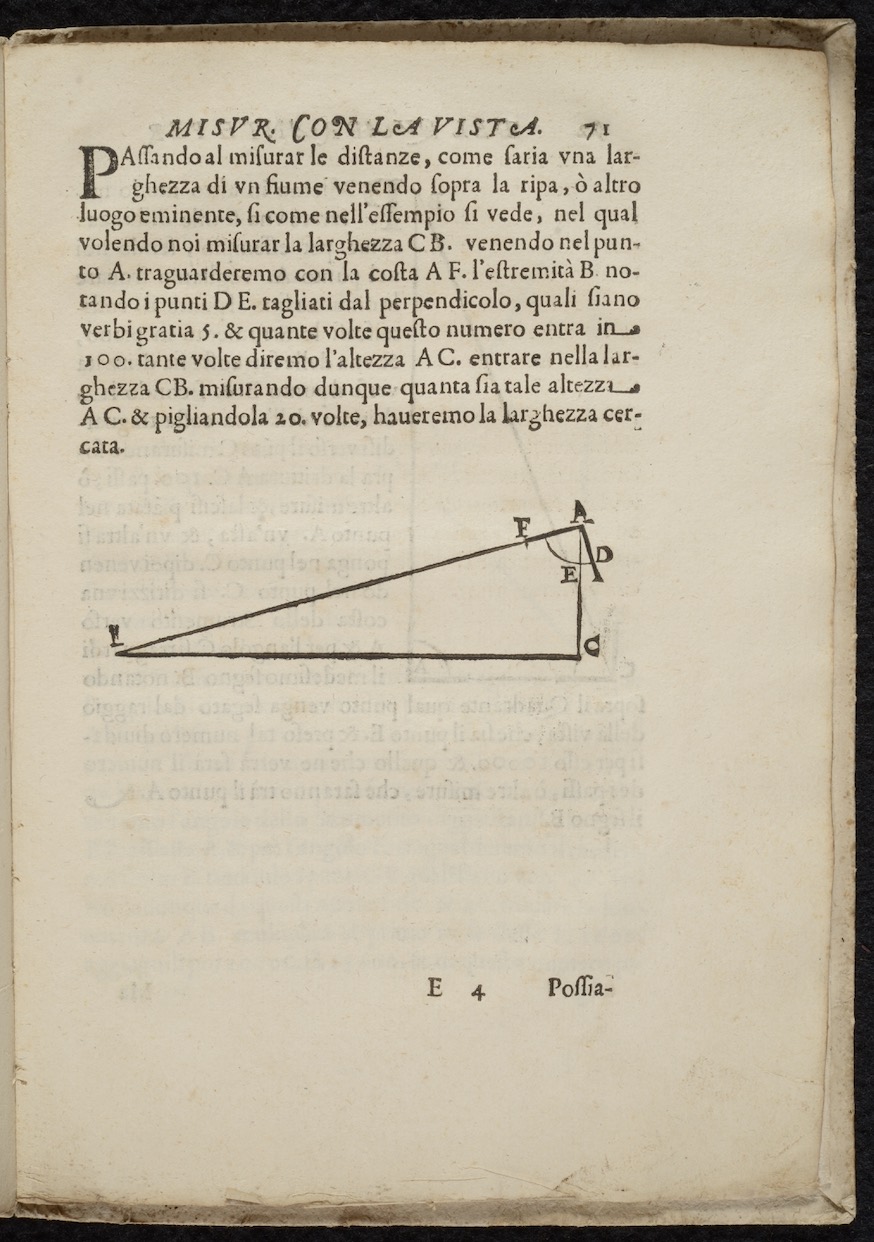

Galileo Galilei. Le operazione del compasso geometrico, et militare.

Padua: Paolo Frambotto, 1649.

Navigating a vessel involved complex geometric calculations, from the elevation of canons on warships, to measuring distances and calculating the weight and volume of objects in cargo.

Renaissance scientists recognized the need to develop an instrument suitable for performing complicated geometric calculations as a result of advances in artillery and navigation. Galileo's compass used proportional lines on the metallic legs of the compass combined with scales on the quadrant to facilitate calculations that involved square roots, volumes and surveying territory. Calculations were needed to compute the trajectory of cannon when attacking larger or smaller vessels on the sea as well as land fortifications. Properly calculating the weight and volume of cargo could save lives by avoiding the risk of capsizing, while it also could increase profit through the accurate measurements of goods in the hold.

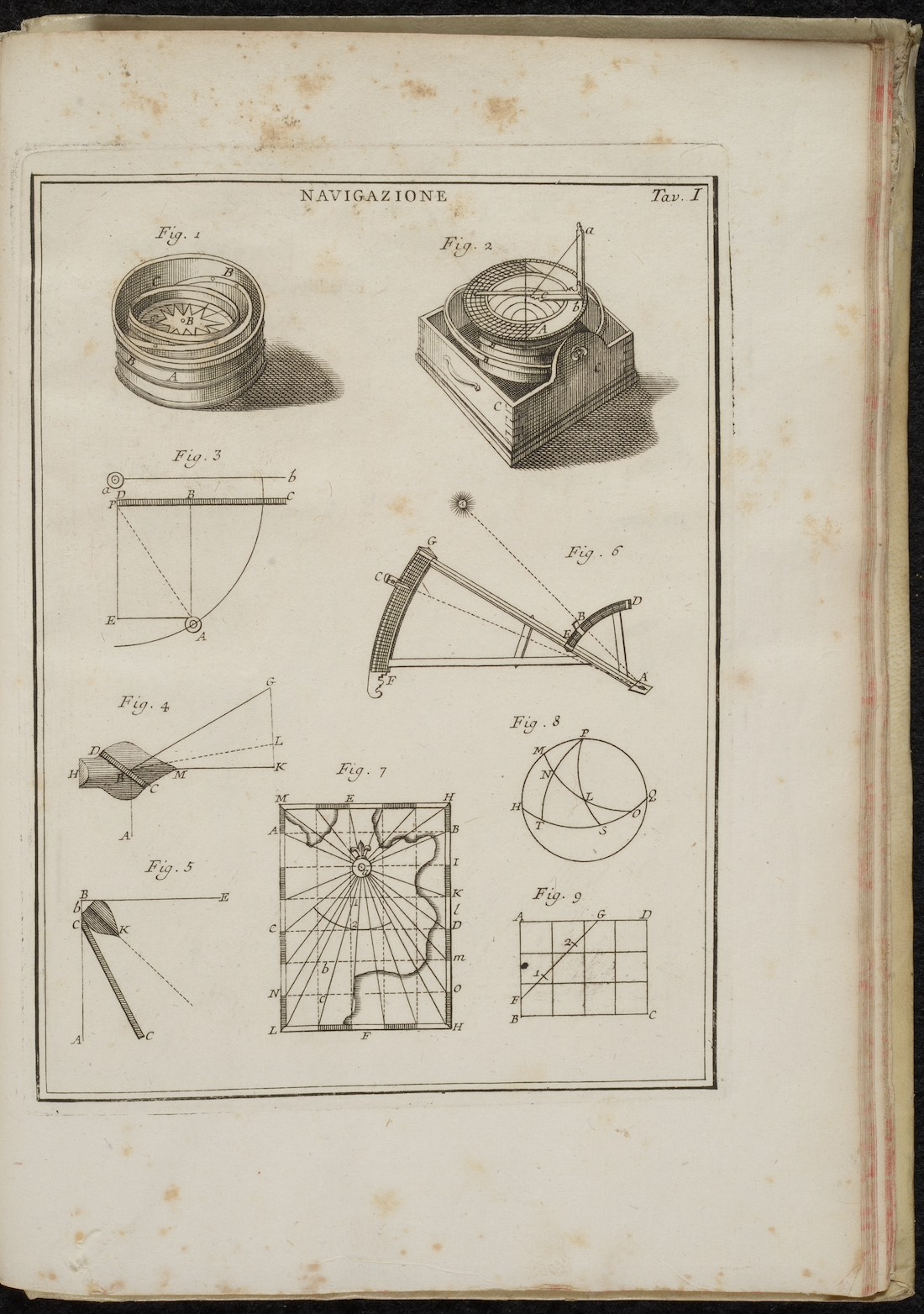

Ephraim Chambers. Dizionario universale delle arti e delle scienze, che contiene la spiegazione de' termini, e la descrizion delle cose significate per essi, nelle arti liberali e meccaniche, e nelle scienze umane e divine. 9 volumes.

Venice: Giambatista Pasquali, 1748-1749.

Determining course, speed and measuring depth increased the Mediterranean captain's ability to outmaneuver danger and arrive safely in port.

The science and tools of navigation improved dramatically in the early modern Mediterranean. Coupled with advances in astronomy, tools such as the 16th-century backstaff (fig. 6) to measure the sun's altitude, when combined with the medieval mariner's astrolabe, allowed for more accurate charting of latitude. Likewise, the ancient Chinese and improved medieval Mediterranean magnetic compass (fig. 1) was later mounted and used with quadrants and sextants in the 18th century to accurately determine the bearing of ships (hence bearing compass) when travelling across open seas and away from landmarks (fig. 2).

Travel and Trade

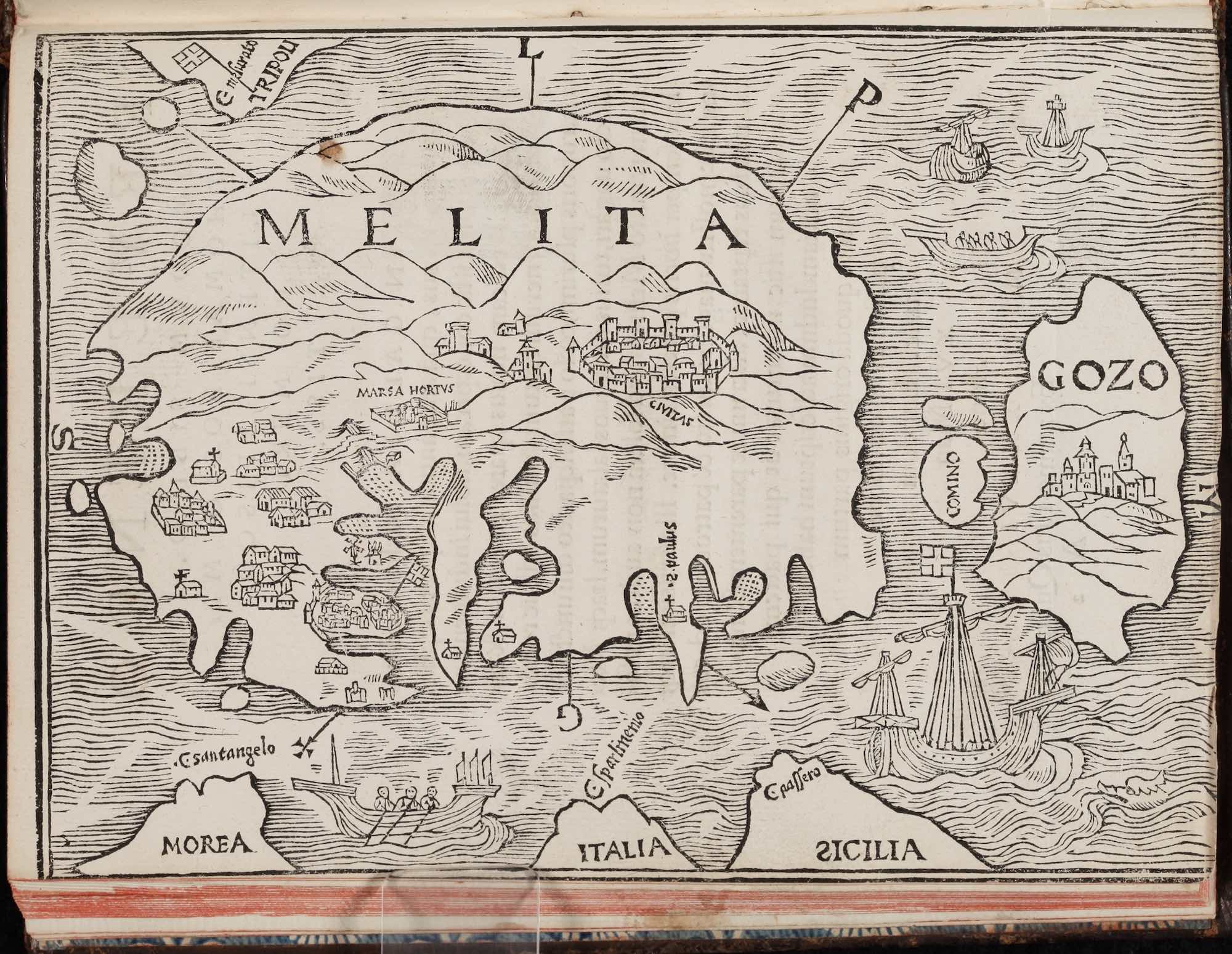

Jean Quintin, Insulae Melitae descriptio: ex commentarijs rerum quotidianorum F. Ioan. Quintini Hedui ad Sophum.

Lyon: Sebastian Gryphius, 1536.

Mediterranean travel narratives often saw much wider circulation than their original publication since their content was copied into works by authors who could not travel to remote islands.

Jean Quintin, a chaplain and knight of the Order of the Knights of Malta, wrote the record of his visit to the Maltese archipelago after the Order took control of the islands in 1530. His detailed discussion of the towns, landscape and sites of Malta became the standard description of the island used by later writers when composing atlases or other geographic works. Quintin's description of Malta, including the first printed map of the island, became the principal source for historians describing the 1565 Great Siege of Malta who had never traveled to the island, giving the text a much wider circulation than the original publication.

![<em>Beschreibung und Contrafactur der vornembster Stätt der Welt [Civitates orbis terrarum]</em>.<br>Cologne?: Georg Braun and Frans Hogenberg, 1574-1600.](../../../assets/img/exhibitions/mediterranean-travel-people-places-encounters/5_2_HMML_00301_IMG_001.jpg)

Beschreibung und Contrafactur der vornembster Stätt der Welt [Civitates orbis terrarum].

Cologne?: Georg Braun and Frans Hogenberg, 1574-1600.

Mapmakers and engravers attempted to provide current representations of cities to create a market for their works among merchants and travelers, even when relying on past models.

Braun and Hogenberg's map “Malta”, which depicts the Grand Harbor and Valletta, is based on Hieronymus Cock's depiction of the 1565 Great Siege of Malta published in Antwerp on 24 October 1565, which in turn was based on Mario Cartaro's map of the Great Siege published in Rome on 20 June 1565. Braun and Hogenberg removed all imagery of the Great Siege, including the Turkish encampments, fleet and battle scenes. Instead, the printers added the fortified walls of the new city of Valletta founded one year after the Great Siege by Grand Master Jean de la Vallette. The map included Baldasarre Lanci's design of Valletta from 1562, which was ultimately rejected by the Order of Malta in favor of a design by Francesco Laparelli da Cortona.

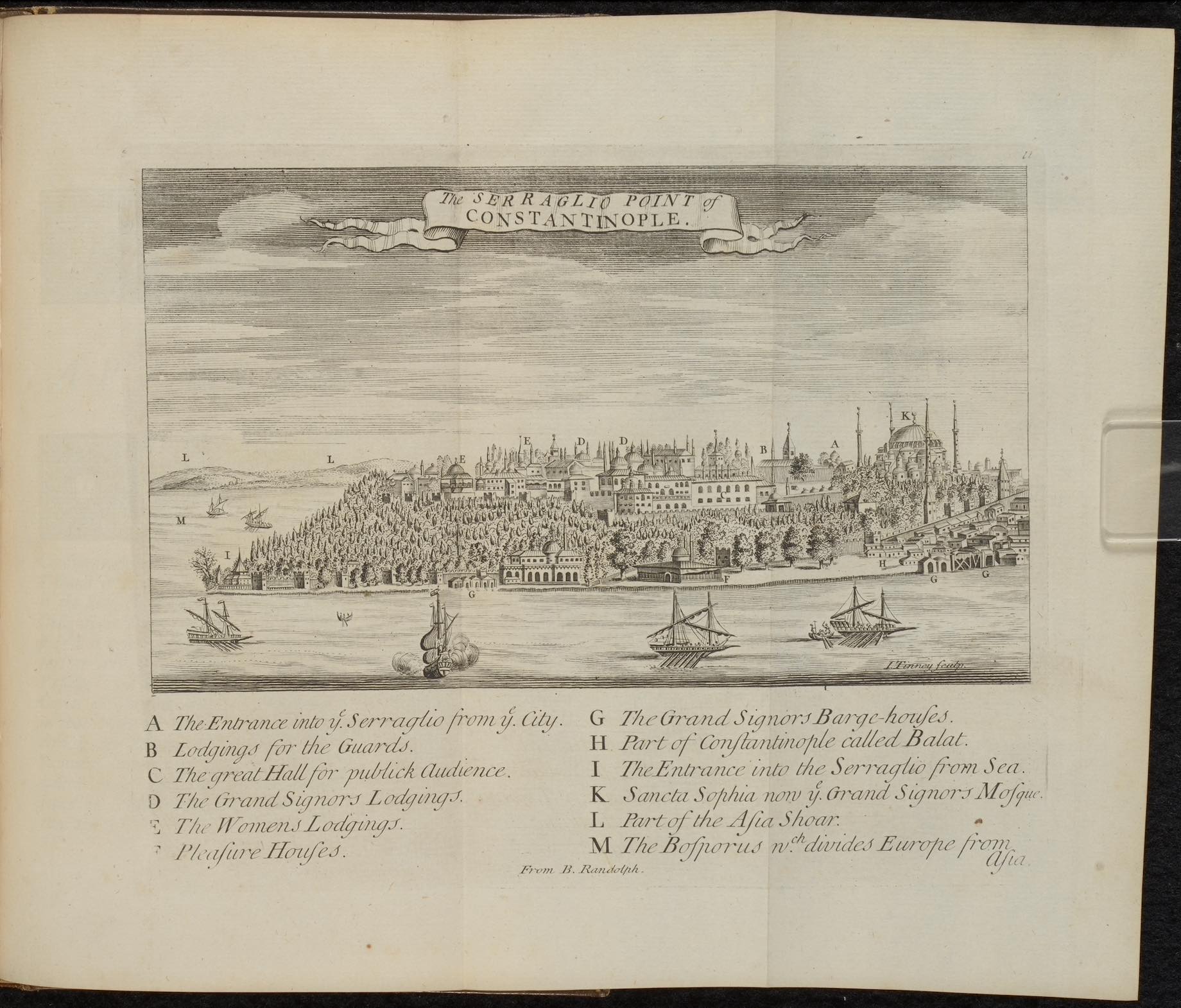

Pierre Gilles. The antiquities of Constantinople. With a description of its situation, the conveniencies of its port, its publick buildings, the statuary, sculpture, architecture, and other curiosities of that city. With cuts explaining the chief of them. In four books. Translated by John Ball. Engravings by John Tinney.

London: Printed for the benefit of the translator, 1729.

Reading classic travel narratives provided young European gentleman with knowledge before undertaking their classical studies in the Mediterranean as part of their grand tour.

John Balls' translation of the sixteenth-century De Topographia Constantinopoleos et de illius antiquitatibus libri IV by Pierre Gilles, showed the continuing importance of older travel narratives as sources for historical information and reference material for travelers. Gilles, who was sent to Constantinople in 1544 by King Frances I of France completed lengthy descriptions of Constantinople and surrounding areas, often copying material from Greek authors such as Dionysius of Byzantium. Gilles' detailed architectural descriptions proved important for 18th-century English gentleman, who used the work to prepare for their grand tour; a journey to the Mediterranean undertaken to cultivate the mind and exorcise the vigor of adolescence.

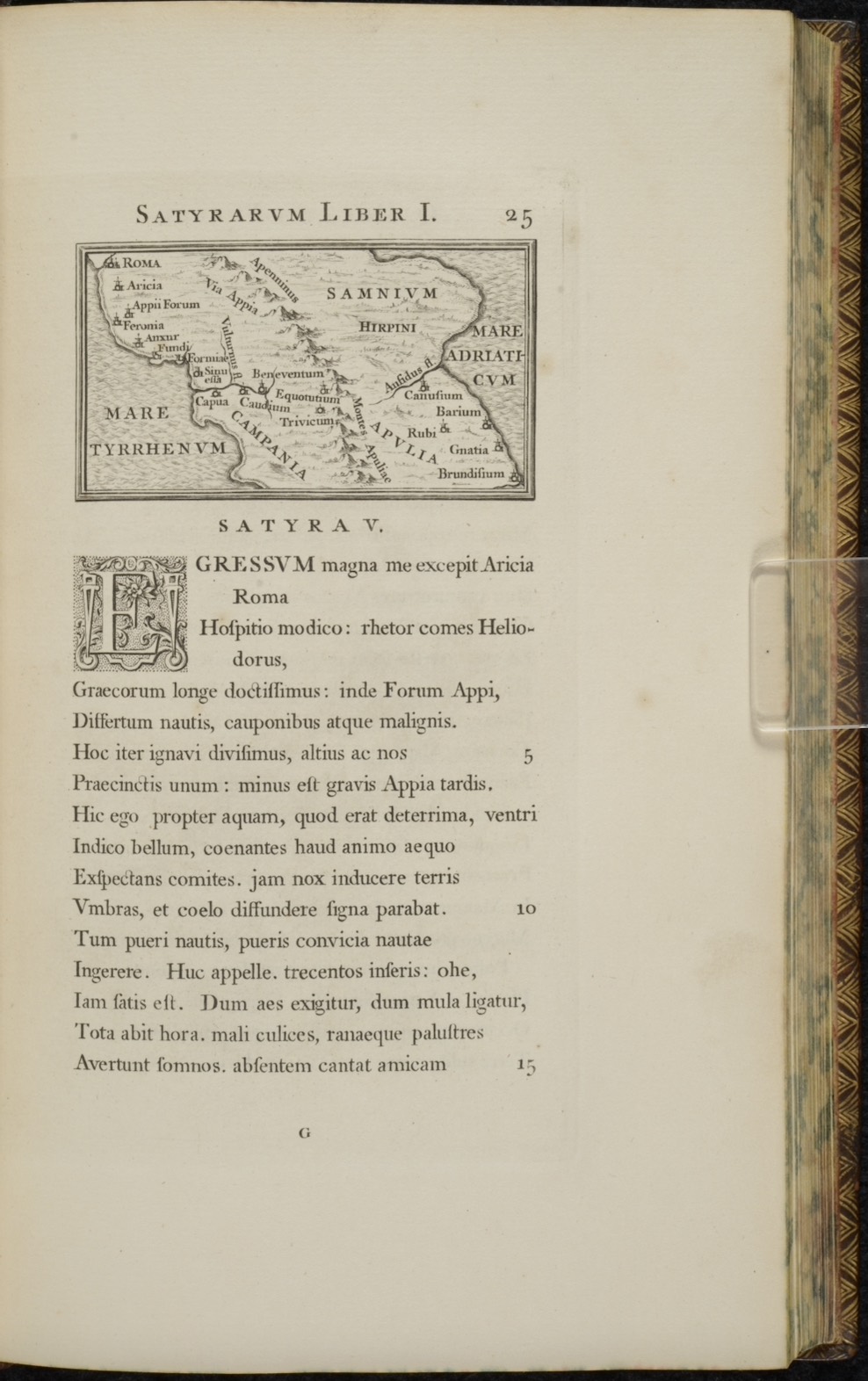

Horace. Qvinti Horatii Flacci opera. 2 vols.

London: John Pine, 1733-1737.

The complicated geography of the Mediterranean and its varying towns and provinces created opportunities for travelers to discuss timeless subjects, even during difficult times.

Horace's Iter Brundisium or Journey to Brindisi (Book I, Satire 5), though grounded in contemporary poetics, created a new style of travel writing by combining timeless philosophical discussions about friends with the comedic circumstances encountered while travelling. Horace's discussion of country inns, recitation of ribald humor and use of comedic banter between friends was set against the dramatic purpose of his journey to mediate the conflict between Octavian and Mark Anthony over the control of the Roman Republic. The use of satire against tragedy set the stage for modern poets, including Giovanni Boccaccio, whose Decameron brought humor and philosophical musing leaving Florence during the plague of 1348.

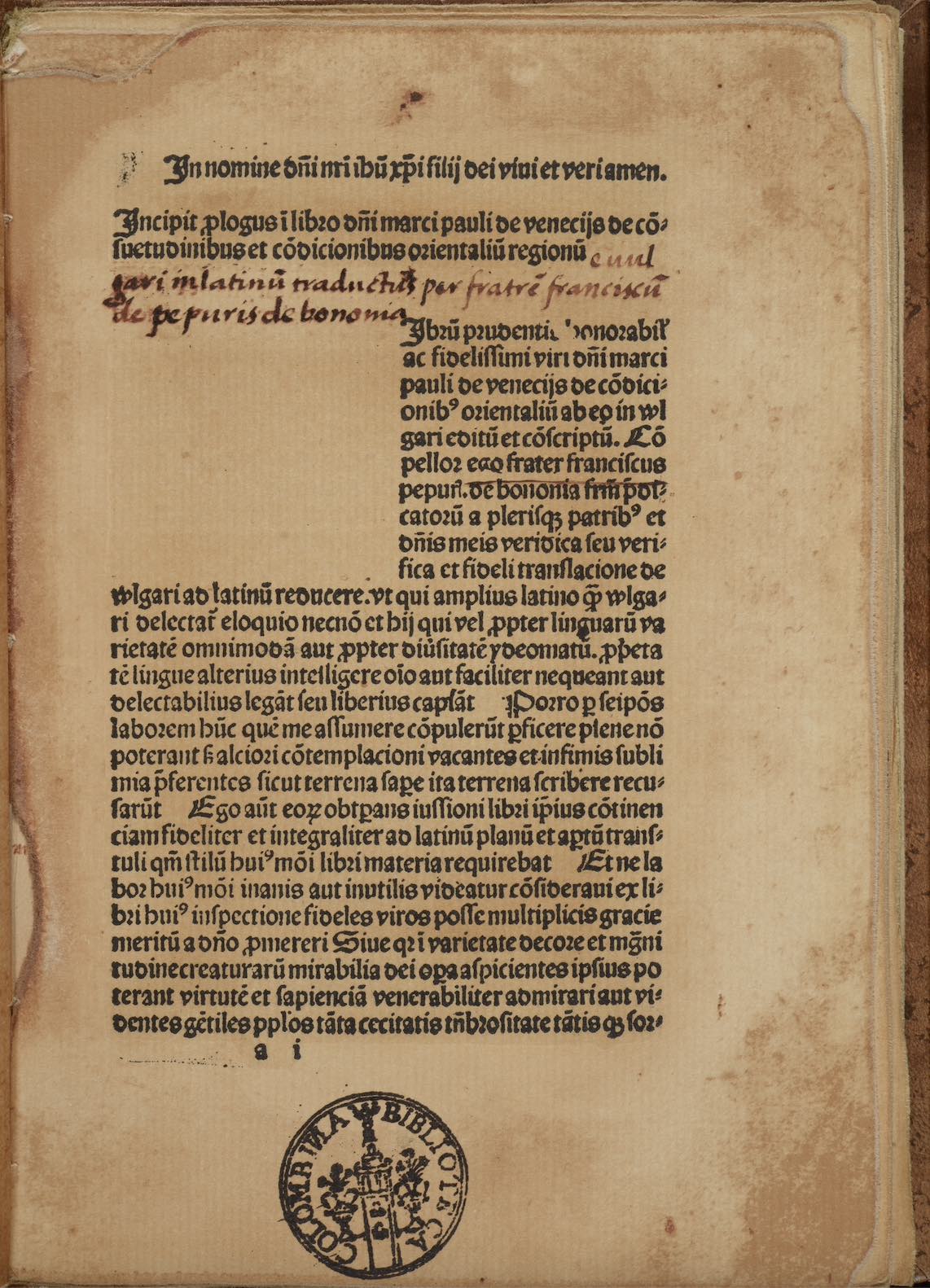

Marco Polo. De consuetudinibus et conditionibus orientalium regionum. Translated by Francesco Pipino.

Gouda: Gerard Leeu, 1483-1485.

Facsimile, Madrid: Testimonio, 1986.

Inspiration to travel in the Mediterranean and beyond often began with reading and taking notes on those who had traveled to distant and unknown lands.

Marco Polo's Livres des merveilles du monde or Book of Marvels of the World became one of the most widely read travel narratives after his return from China in 1295. While in a Venetian prison, he dictated his account to Rustichello da Pisa, whose French text became widely read in Europe. The Latin translation completed by Francesco Pipino before 1317, and printed between 1483-1485 by Gerard Leeu, proved highly popular and inspired several explorers with tales of adventure, including Cristobal Colón, whose personal copy presented here contained numerous annotations and marginal notes that would be incorporated into his own description of the Caribbean Islands encountered in 1492.

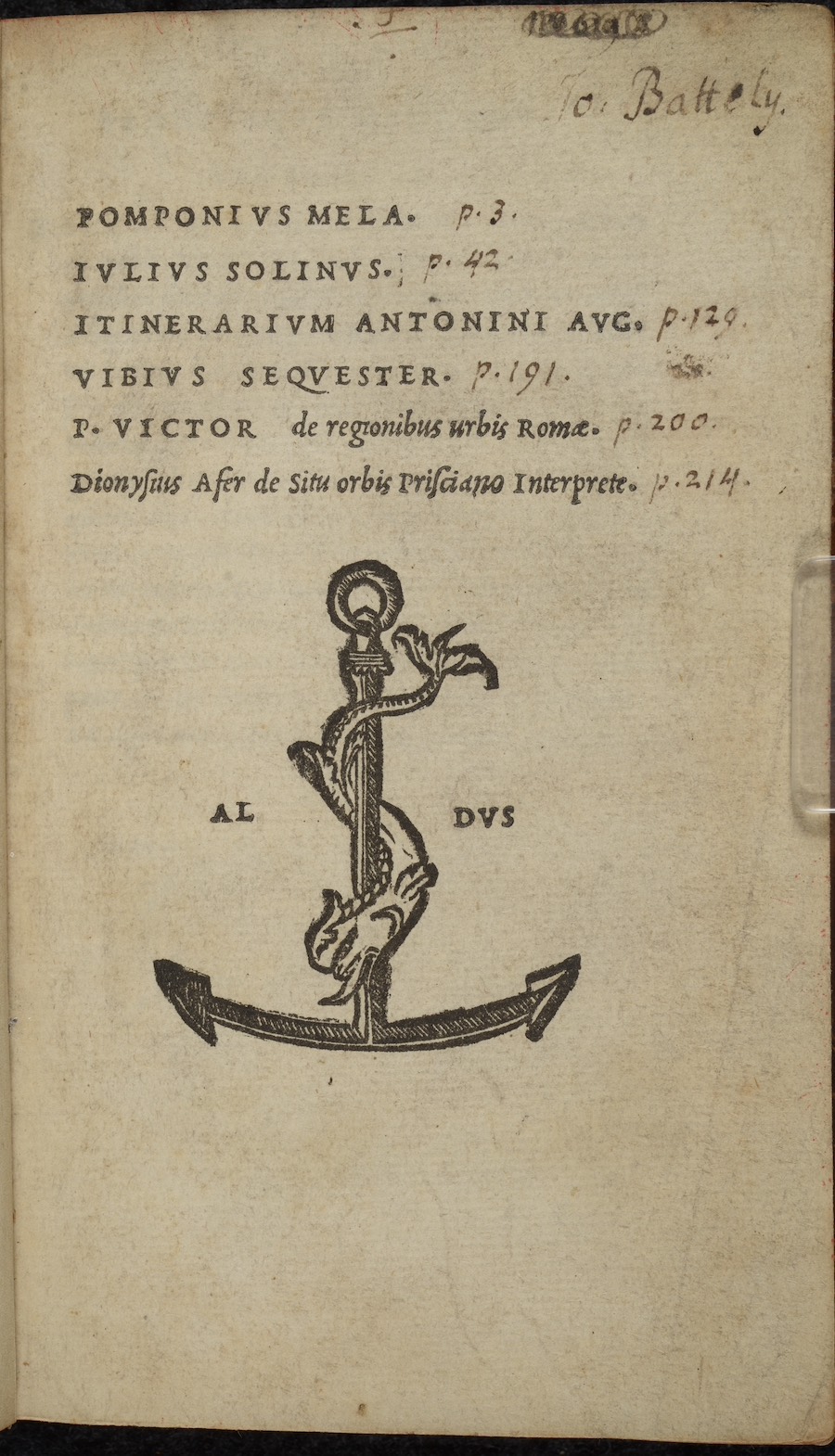

Itinerarivm provinciarvm Antonii Avgusti.

Venice: Aldus Manutius, 1518.

Guidebooks describing distances between cities offered travelers practical information not found in common travel narratives.

Traditionally attributed to the Emperor Antoninus Pius, the Itinerarium provinciarum or Journey of the Provinces is a register of the roads in the Roman Empire dated to the early third century. Unlike most travel books, the Itinerarium provinciarum provided nothing more than a survey of Roman roads and the distances between cities within the various Roman provinces. Though sparse in detail, the work contains unique information on the location of Roman roads and the importance of measuring distances between towns before transporting goods or undertaking a journey. Though seemingly out of date when published in 1518, many of the Roman roads remained in use during the middle ages and early modern period.

Andreas Walsperger, Mappa mundi.

Constance, Switzerland, 1448

Late medieval map makers reimagined geography based on the accounts brought back to Europe from travelers who ventured to Asia and around Africa.

Andreas Walsperger's World Map or Mappa mundi intricately detailed the geography of the known world based on his knowledge of classical and medieval sources. Walsperger also used new information brought back to Europe from recent voyages to Asia and Africa. This knew information led Walsperger to invert the orientation of the Earth, placing Africa above Europe. Despite the change in its orientation, the map retained its medieval Christian perspective with Jerusalem as the center of the world.

Curator(s)

Dr. Daniel K. Gullo

Credits

I wish to extend my thanks to Tim Ternes, Claire Kouri, and Mark Spangler for helping install the exhibition and creating a wonderful display. My thanks also to Dr. Matt Heintzelman and John Meyerhofer, who helped prepare the physical materials and online exhibition. The exhibition “Mediterranean Travel - People, Places, Encounters” was originally shown in June 2018 as part of the 2018 NEH Summer Institute “Thresholds of Change: Modernity and Transformation in the Late Medieval and Early Modern Mediterranean, 1400-1700” led by Dr. Kiril Petkov.