The Golden Age Of Spain

The Golden Age of Spain

Contributions to a Changing World

The Golden Age of Spain was an era of political consolidation due to the rise of the Habsburg dynasty. United through the marriage of King Fernando of Aragon and Queen Isabel of Castile, Spain emerged politically stable from a period of prolonged warfare. With the defeat of Al-andalus (Muslim Spain) and expulsion of Jews, the many Christian kingdoms came together to form a unified state.

The Spanish Empire arose in a period of social, religious, and intellectual change in which plants and animals were indexed, new understandings of human anatomy developed, and the Inquisition sought to promulgate Spain’s Catholic identity.

Some saw the empire as corrupt and cruel. They critiqued the Inquisition’s methods, Spain’s treatment of indigenous peoples and non-Catholic cultures, and the excesses committed against Protestants in post-Reformation religious wars. This negative portrayal of Spain, known as the ‘Black Legend,’ outlasted the empire; even today, many people do not recognize the importance of Spain to Renaissance Europe’s history.

This exhibit seeks to undo the marginalization of Spain from European history, not to glorify its actions, but rather uncover how the Spanish Empire helped shape the modern world.

Contributions to a Changing World

The Golden Age of Spain (1492–1700) was a period of flourishing artistic production. Renowned authors such as Miguel de Cervantes, Félix Lope de Vega, Pedro Calderón de la Barca, Francisco Quevedo, Luis de Góngora, and others increased the prestige of Spanish as a literary language by utilizing innovative Renaissance genres, such as the sonnet, and revitalizing traditional Spanish genres, like the romance (a traditional poetic form). Golden Age Spanish painters included “El Greco” (Doménikos Theotokópoulos), Diego Velázquez, and Bartolomé Murillo. Architectural schemes such as the Plateresque style flourished.

Several key factors contributed to the cultural advances of the Golden Age. The political unification and relative stability of the Habsburg era and the invention of the printing press in 1450 allowed for the rapid spread of knowledge and increased production of texts. Renaissance literature and art began to emphasize the individual, in contrast to the Medieval focus on community, and articulations of individual liberty and human rights began to emerge that would eventually give rise to the Enlightenment.

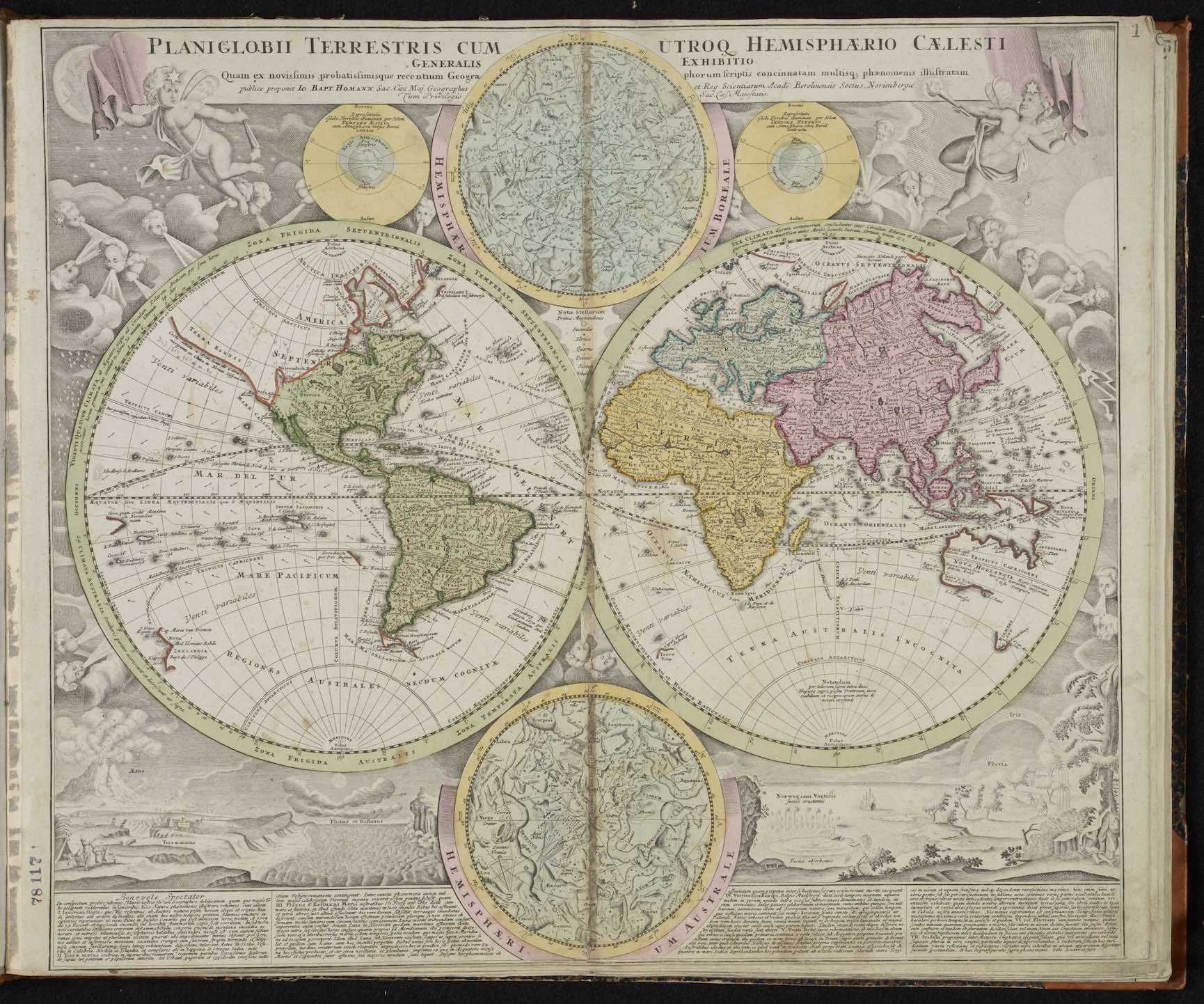

Mappe monde ou description du globe terrestre (World Map)

Spain was a global empire for over 200 years, almost as long as the United States has been a nation.

Although small itself, Spain controlled vast amounts of land. At its height, the Spanish Empire had territories on six of the seven continents. As seen on this map, its influence stretched from the Philippines to modern-day New Zealand, Mexico, and Italy. Spain was able to control such vast terrain by developing a strong, centralized government and efficient bureaucracy in addition to being one of the largest maritime powers.

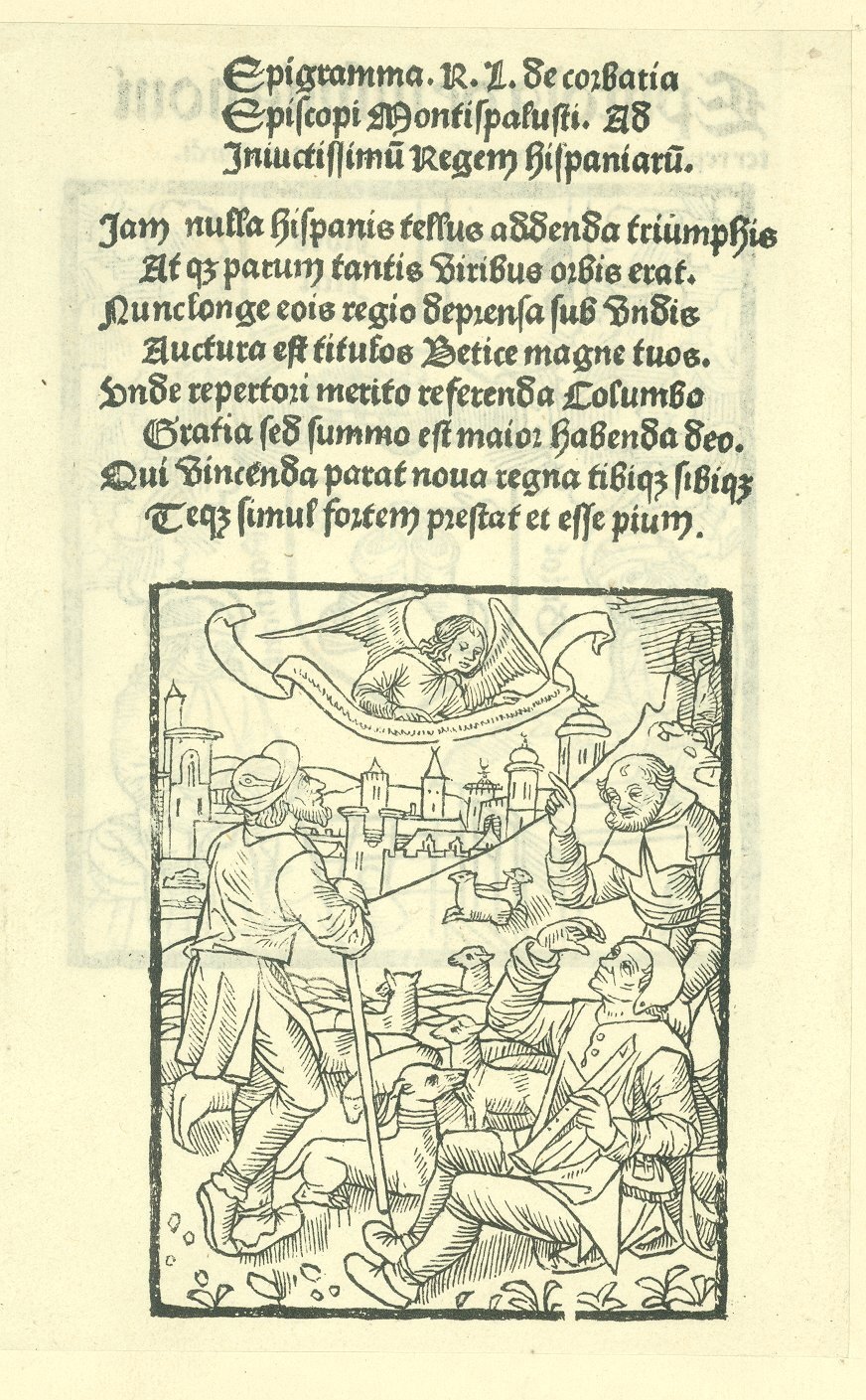

Letter Concerning the Newly Discovered Islands

Spreading the Faith...

A biblical image of angels bringing the news of Jesus’ birth to the shepherds illustrates this reproduction of a letter written by Christopher Columbus, detailing his voyages to the Americas. Such religious imagery demonstrates the Spanish justification for imperial expansion: they saw themselves as a new ‘chosen people’ with a divine mission to spread Catholicism through conquest and forced conversion.

Supposedly composed during his 1492 voyage, Columbus’ letters describe his island “discoveries.” These were printed, first in Spanish, then Latin, and later in Italian and German. Several editions appeared in rapid succession across Europe, including three printed by Guy Marchant in Paris. The printer’s device from Marchant’s third edition shows two people preparing leather to make shoes, while the title verso (pictured) includes a poem highlighting Columbus’s achievement and a woodcut that draws a parallel between the angelic announcement of Jesus’ birth to the shepherds and Columbus’s desire to spread the word of God to the ends of the earth.

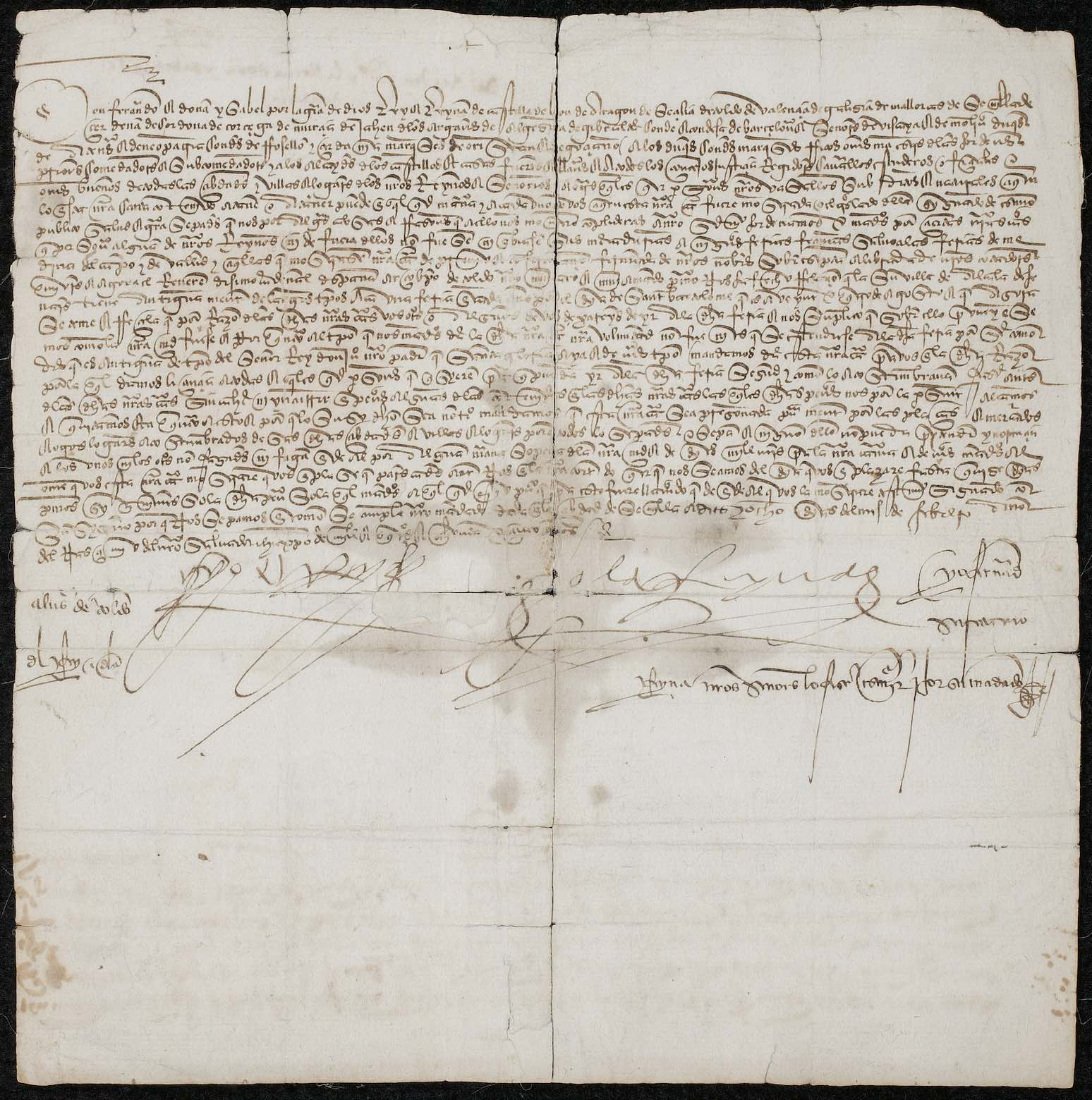

Charter of Isabel I, Queen of Castile and Leon, and Fernando V, King of Castile and Leon.

“Don Fernando and Doña Isabel, by the grace of God, King and Queen of Castile, of Leon, of Aragon, of Sicily, of Toledo, of Valencia, of Galicia, of Mallorca, of Seville, of Sardinia…”

This charter, composed in 1478 by King Fernando of Aragon and Queen Isabel of Castile (also known as the Catholic Kings), describes the various regions Spain controlled immediately following their union. Although they reigned separately, their children would inherit their combined kingdoms. The nameless signatures—“I the King” and “I the Queen”—exemplify the immense power held by the monarchy during this era.

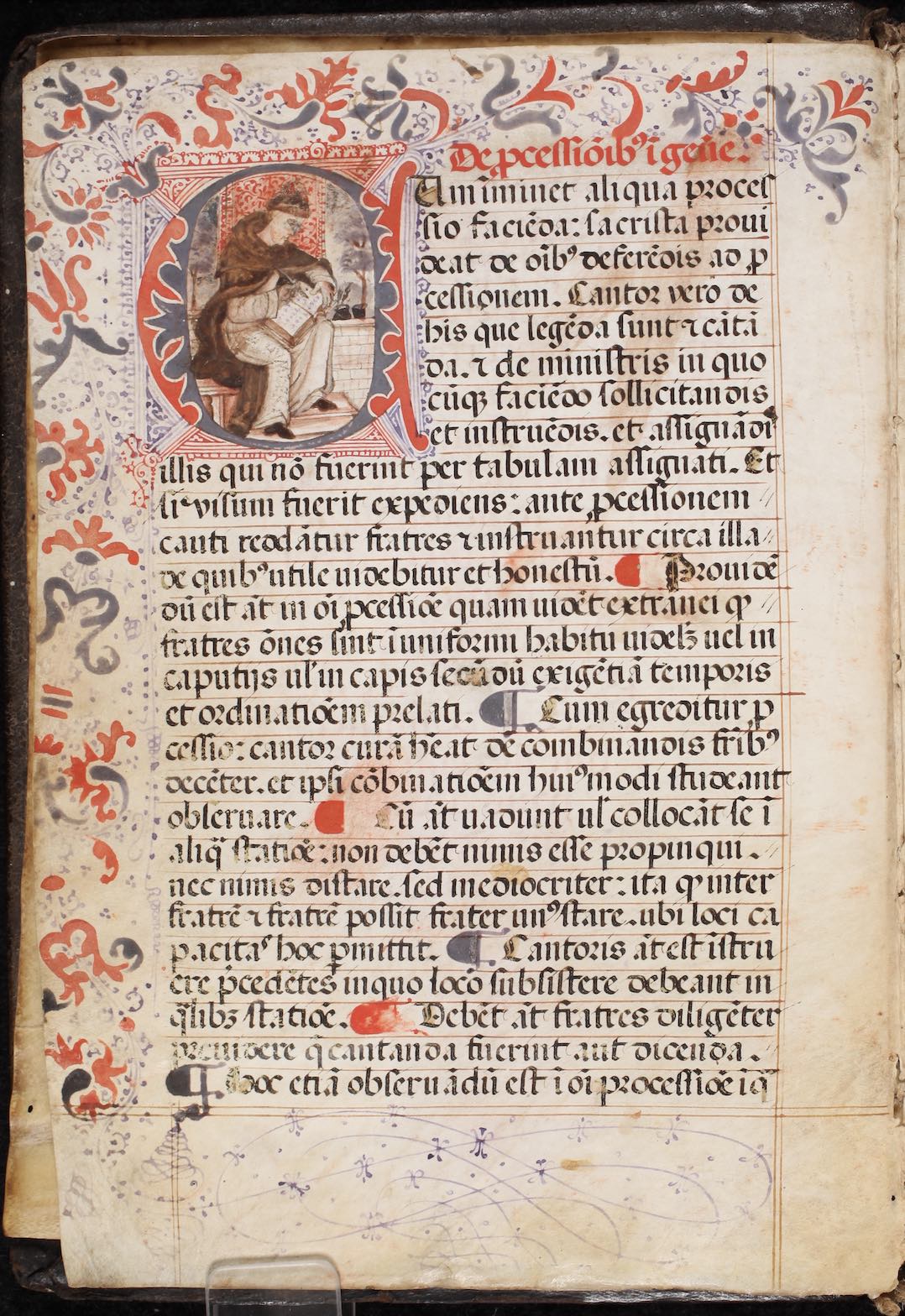

Dominican Processional

The Golden Age brought about inventions that changed centuries-old traditions.

In the Middle Ages, monks, such as the one depicted here, were often tasked with copying manuscripts. Members of monastic communities were often some of the most educated people in society, taught to be literate so that they could read and understand scripture. This practice greatly diminished at the beginning of the Golden Age as the printing press enabled wider circulation of books and other traditionally written materials.

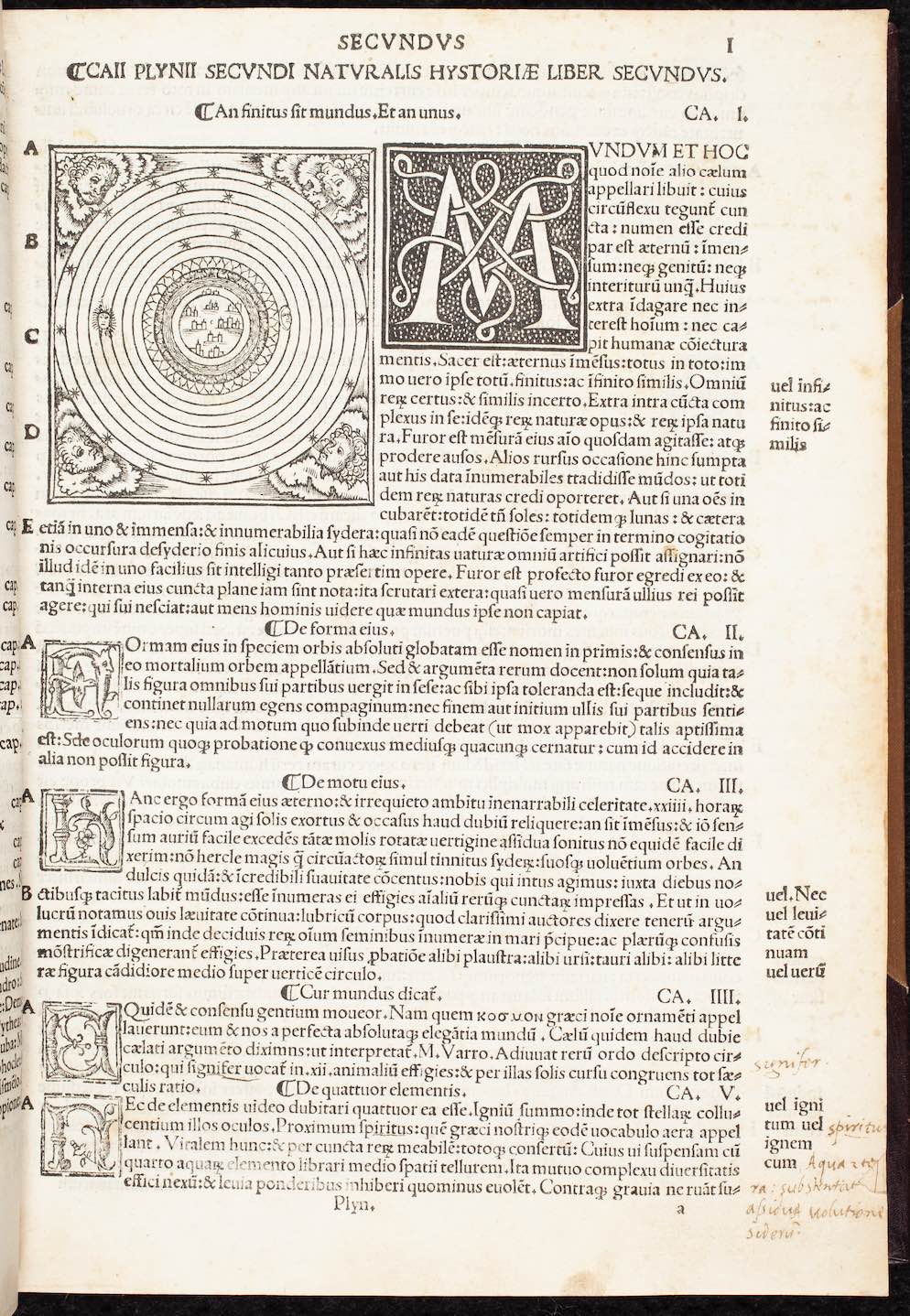

Natural History

Inherited knowledge.

Alongside the movement to explore the world came the urge to find and publish ancient texts. Among these was Naturalis historia (Natural History) by Pliny the Elder, who died in 79 CE, during the eruption of Vesuvius that destroyed Pompeii. In this printed copy, we see a model of the geocentric universe inherited from the Greco-Roman tradition and representative of the 16-century conception of a fixed earth encircled by stars and planets rotating in concentric spheres. As technologies such as the telescope allowed humans to observe more closely or to see farther into the skies, new discoveries gradually began to challenge established epistemologies.

Politics of the Golden Age: From Fragmentation to Empire

The monarchy played an integral role in Spain’s global expansion and influence. As the Habsburg successors to King Fernando and Queen Isabel, King Charles V and his son, King Philip II, continued the legacy of their predecessors through exhibitions of the country’s power and imperial might.

Within the Spanish territories themselves, the king established a strict hierarchy of nobility and wealth, with power embodied by the monarch. This power structure set the standard for how Spain presented itself to other nations. In the Americas, specifically New Spain (modern-day Mexico), Spain strove to create a quasi-Spanish society. Imposing a strict hierarchy via appointed officials and thousands of laws, the Crown continued its tight control and limited the holdings of individual wealth. In Europe, Spain practiced a more diplomatic imperialism, placing Spaniards in key governmental positions and leaving pre-existing government structures intact.

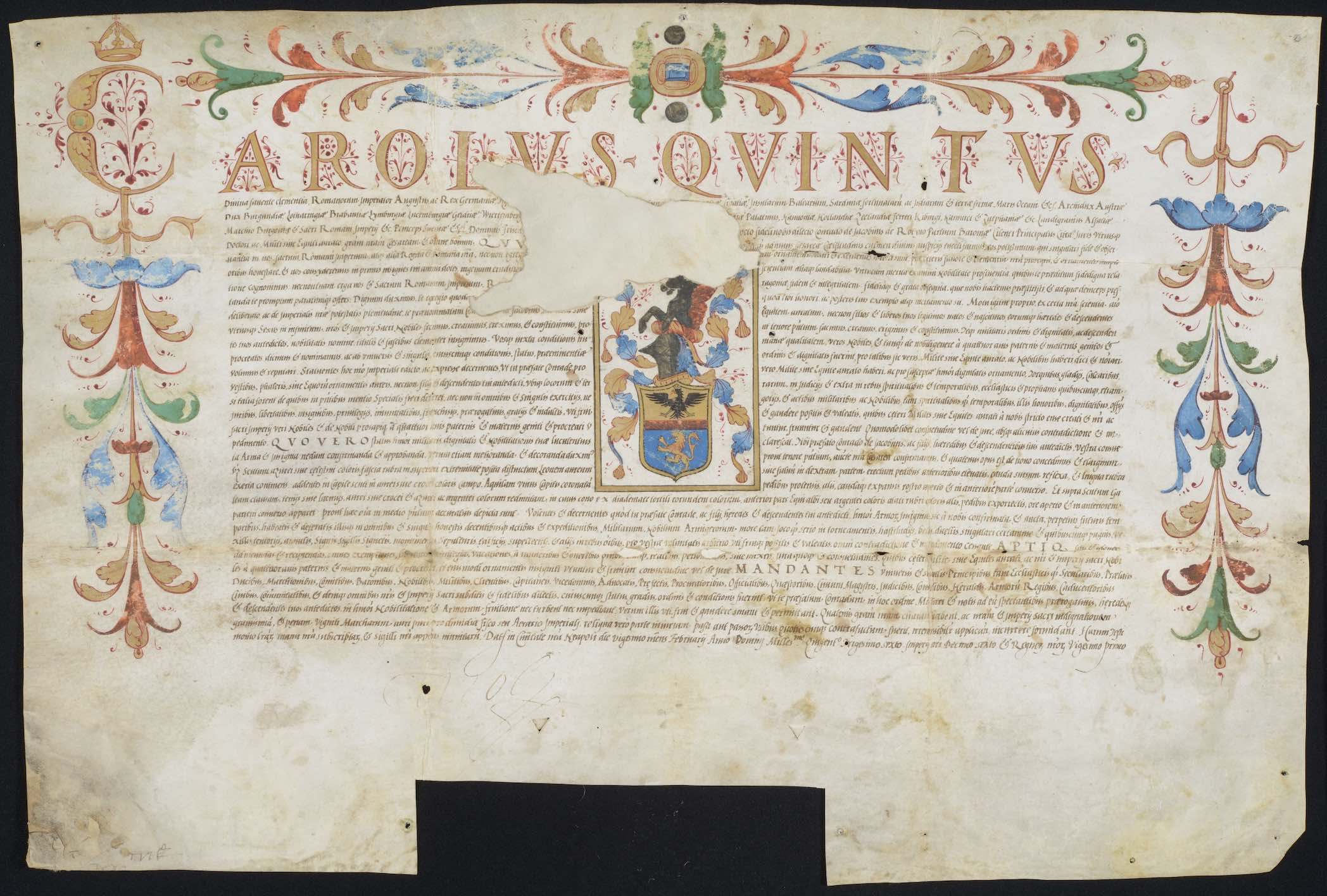

Patent of Nobility

Spanish nobles were separated into two main groups: titled nobles (grandees) and untitled nobles (hidalgos). The king referred to grandees as “my cousin,” whereas untitled nobles were referred to as “my kinsman.”

This patent of nobility was a legal document used by Charles V to grant a title to an unknown individual. Patents of nobility were often created to determine the order of succession for a specific title. The image in the center likely depicts the coat of arms for the recipient of the patent.

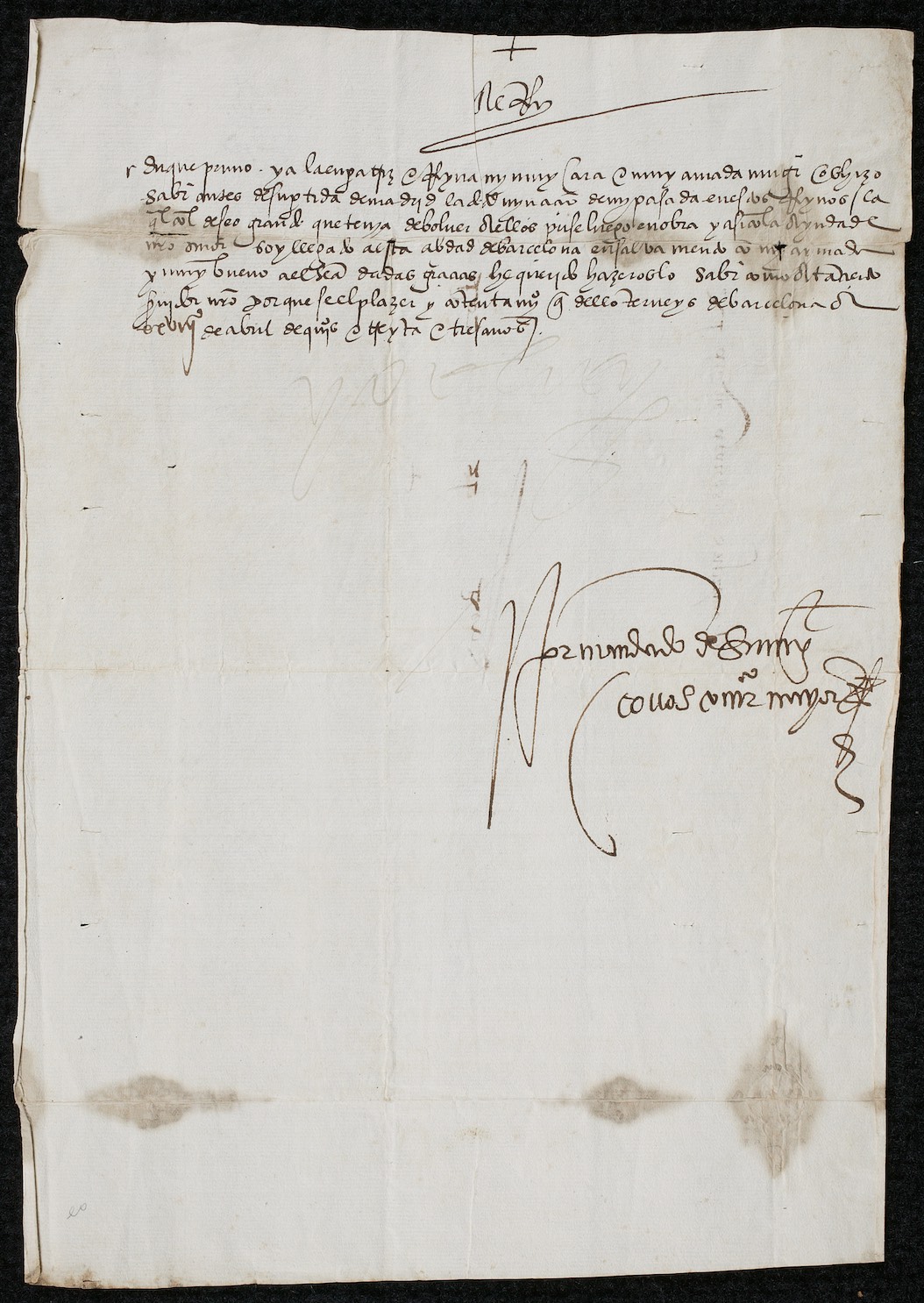

Letter of King Charles I of Spain (Charles V of the Holy Roman Emperor)

Nobles were granted land by the king for a variety of reasons, including their services to the empire.

This letter, signed by King Charles V, was written to a duke regarding a previously agreed upon land transaction. The text begins with “My loving cousin,” which may refer to the relationship between the king and the duke. The granting of land by the king to whomever he chose demonstrated his power and authority as well as the well-established hierarchy within the empire.

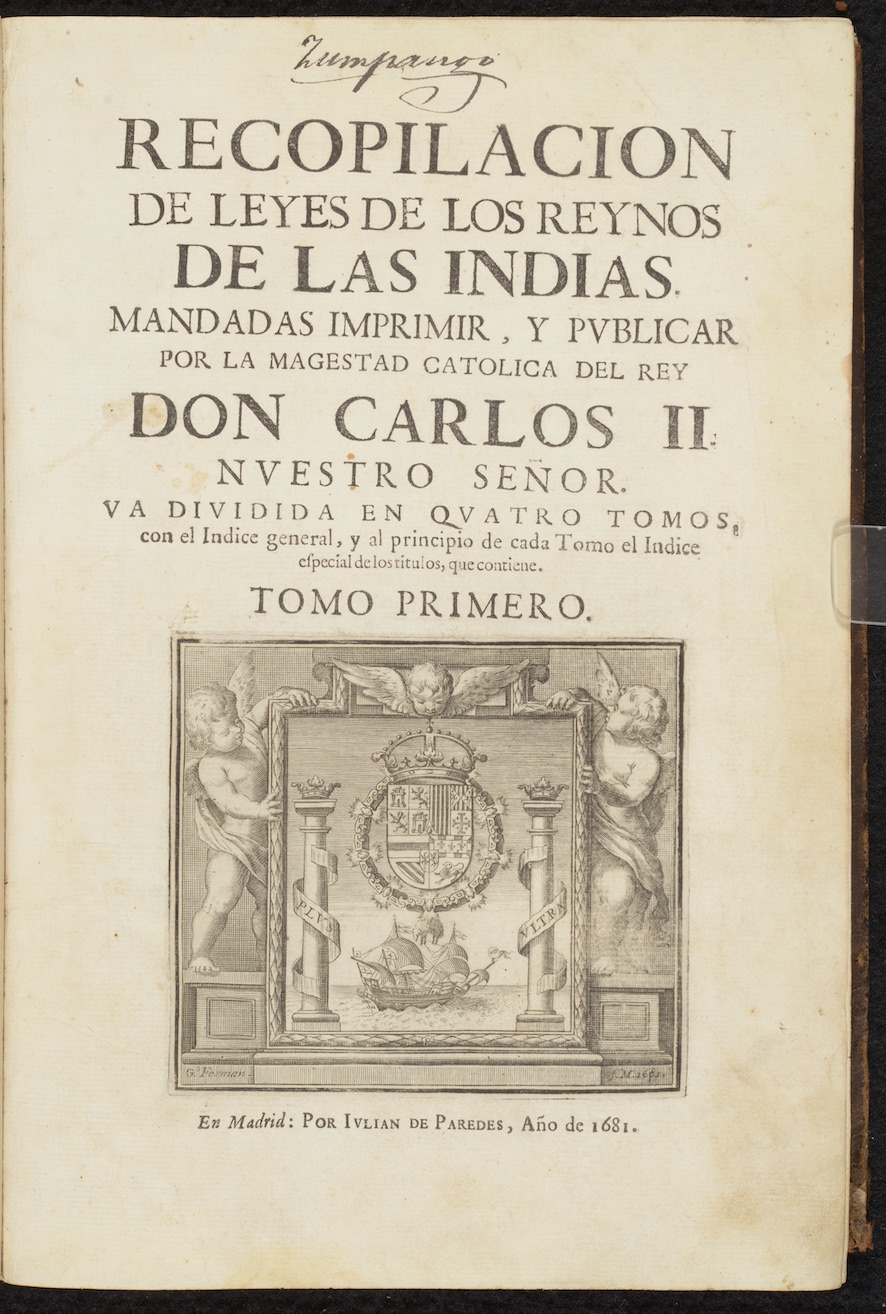

Collection of Laws of the Kingdoms of the Indies

Spain’s imperial control spilled over into the West Indies (Americas) through royal proclamations, laws, and individually-appointed government officials.

This book is one of a four-volume set of rules and regulations put into place to regulate the Spanish state in the colonies. The monarchy regulated the distant colonies through bureaucratic control of appointed officials and recognition (at least on paper) of the colonies’ rights as part of Spain. Notice, however, that many different aspects of life are represented, including hospitals (hospitales), Inquisition Offices (Oficio de la Inquisición), and monasteries (monasterios).

Description of the Low Countries

The presentation of King Philip II with the crests of the Low Countries represents an assertion of power and authority.

In this 1588 book, notice the way that the Low Countries’ crests encircle and almost support the Spanish King’s crest—reminiscent of the colonies’ financial support for the empire. This arrangement also demonstrates how Spain bolstered its powerful image via colonies. The portrait of Philip II, surrounded by Classical imagery, reinforces the idea of Spain as the new Roman Empire. Written in Italian, this book transmitted these ideas to outside countries—specifically Italy, an area of significant cultural influence.

Iconography of the Monastery of St. Lawrence of the Escorial to King Philip II of Spain

El Escorial is a symbol of the power, authority, and wealth of the Spanish Empire.

This engraving displays the Escorial, the former residence of the Spanish monarch, which served as a monastery, basilica, library, and more. Philip II ordered the construction of the Escorial with funds earned from the Spanish colonies in the Americas. This fortified building signifies Spain’s strength throughout the world and exemplifies the interconnectedness of education, politics, and religion during this time.

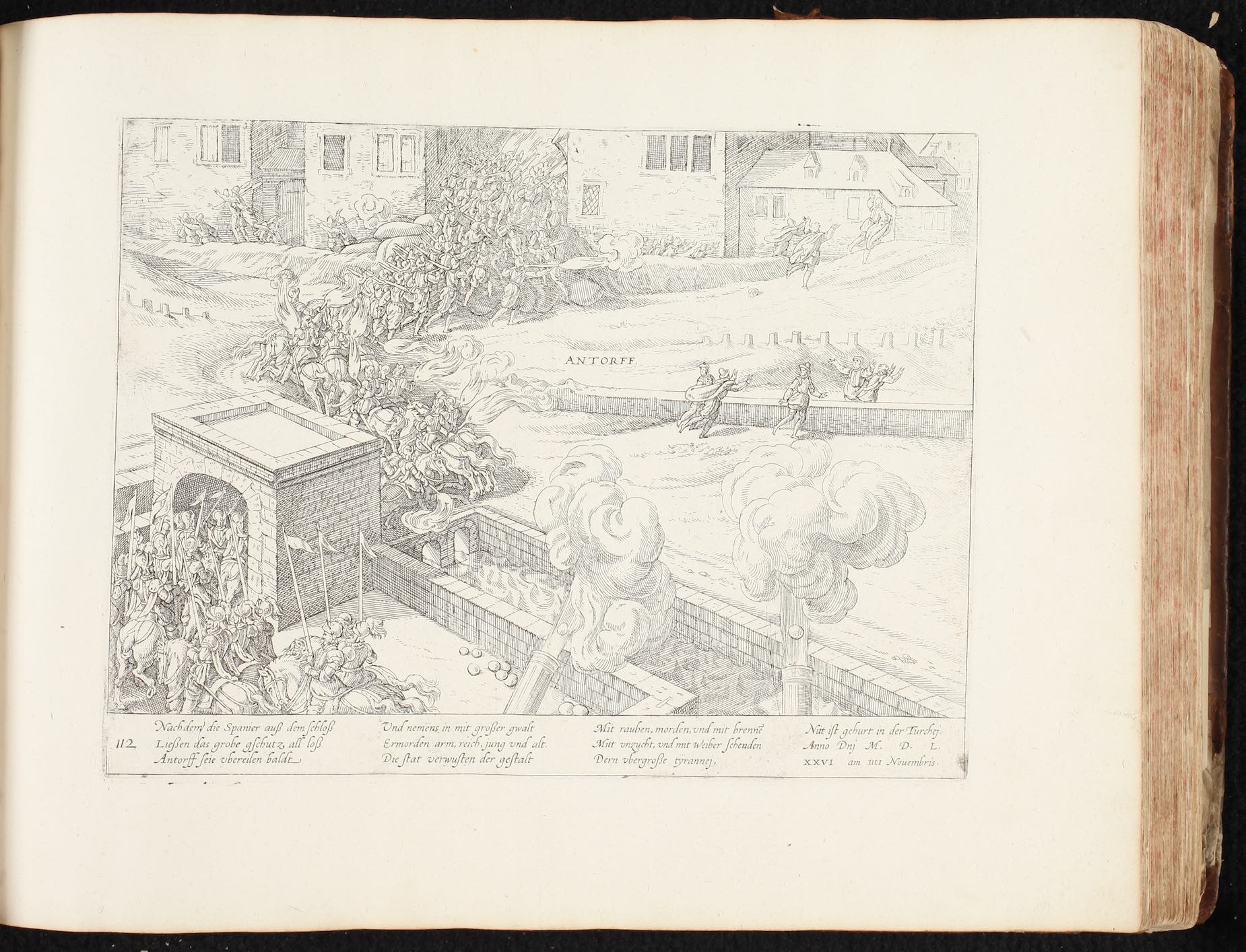

Spanish Fury in Antwerp

Spain’s Black Legend gradually developed in the Low Countries.

This engraving, part of a bound collection of engravings, depicts one of the most infamous rampages of the Spanish Fury where Spanish forces sacked communities across the Low Countries after Protestantism had taken root there. This blatant violence fed into the Black Legend, amplifying existing anti-Spanish narratives and weakening the Empire’s influence. Easy-to-remember rhymes, like the German lines seen here, were popular ways to spread anti-Spanish propaganda.

Reformations and the Inquisition

The Golden Age was a time of great change, both inside and outside of the Catholic Church. Spain and the Catholic Monarchs sought a unified state in which all practiced one, “true” religion: Catholicism. Thus, the Inquisition was instituted to enforce conversion and to seek out false converts. Jews and Muslims were specifically targeted. After the Protestant Reformation in 1517, the Inquisition also persecuted and executed Protestants in Spain and Spanish territories. Meanwhile, within the Catholic Church, the Counter-Reformation was taking place.

This movement to reform the Church from inside prompted the Council of Trent which, among other things, established cloister for nuns (strict enclosure within the convent), ended indulgences (payments to absolve sin), and banned clergy members from having lovers. “Heretics” were also target of the Inquisition post-Council. Although many people were investigated and not convicted, torture was not uncommon, and there was a widespread fear of the Inquisition in Spain and its territories.

Monk (Latin America)

Catholic missions were at the core of Spanish imperialism.

Missionaries from Spain became a prominent part of the colonization of Latin America. This statue shows a Spanish monk dressed in typical, simple attire: a robe with a waist band, no shoes, and the classic tonsure (shaved crown hairstyle). Even though the arms are missing from this piece, one can imagine the monk’s arms outstretched, serving in the name of the Lord. Although missionaries nearly destroyed indigenous Latin America, the Church and its followers described their work as saving the ‘pagan’ citizens of the colonies.

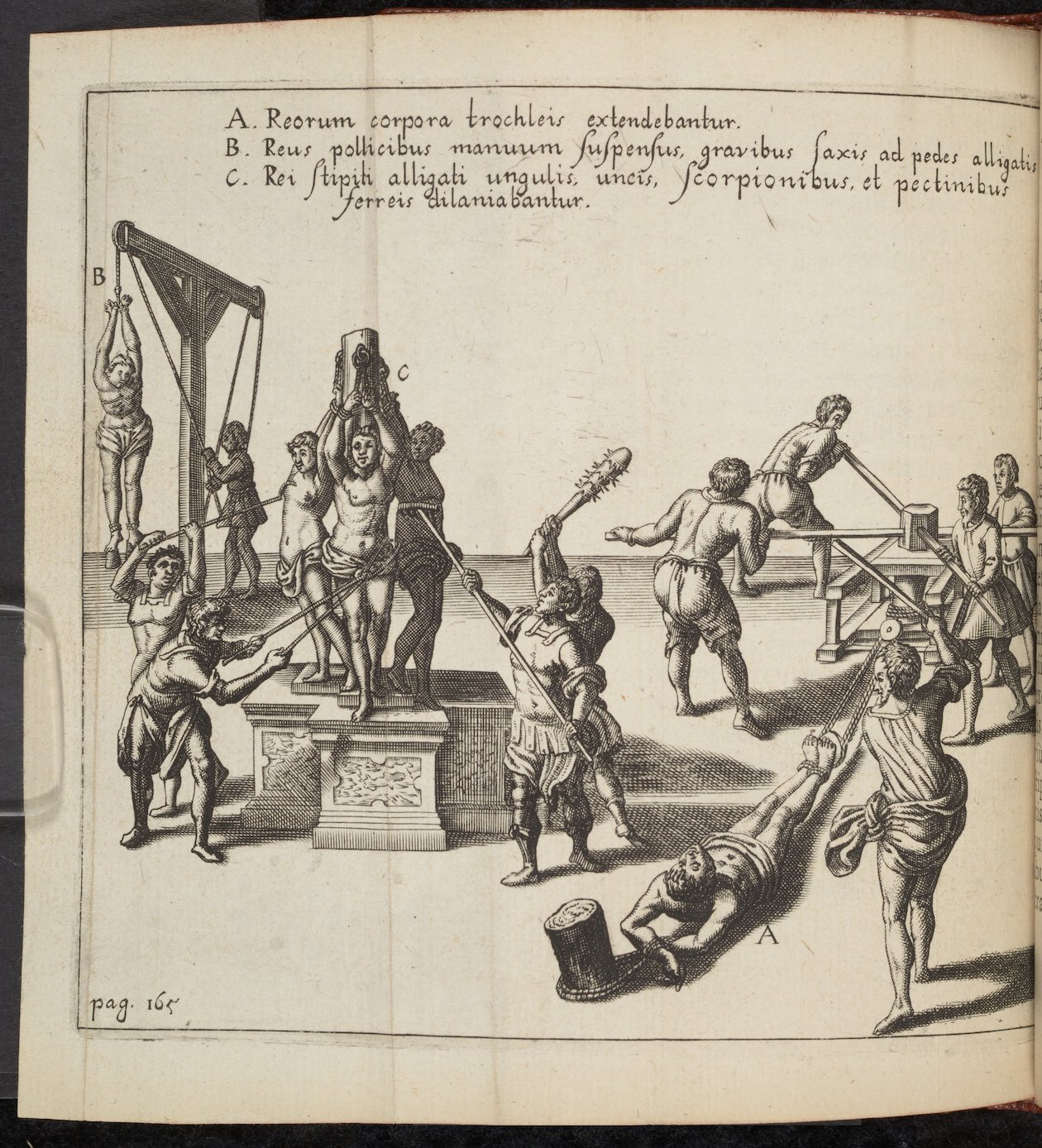

De Equuleo (Concerning a Little Horse or The Rack)

Rooting out heresy.

The Inquisition used torture to force the imprisoned accused to confess. Several different methods are depicted here, including the rack (righthand side). As pictured, ropes were tied around the victims’ arms and legs, eventually dislocating them. It could even tear the limbs off the body. The Inquisition was renowned for such gruesome torture.

Spanish Orations at the Council of Trent

Spanish leaders gave speeches to the Council of Trent that reinforced Spanish doctrine.

Pope Paul III called the Council of Trent in 1545 to formulate the Catholic Church’s response to perceptions of corruption and the threat of Protestantism. Shown here is the cover page of a collection of Spanish leaders’ speeches and sermons at the Council of Trent, meant to reinforce Catholic orthodoxy. The Council of Trent crafted a number of policies meant to strengthen and unify the Catholic faith.

Rule of Saint Benedict

Monks would carry a book of this size so that they always had access to the text.

Here we see a Spanish translation of the Rule of Saint Benedict. The Counter-Reformation saw the emergence of new religious orders, like the Jesuits, and reformed suborders, like the Discalced Carmelites. Older orders, such as the Benedictines, Franciscans, and many others, however, remained powerful and influential throughout the Counter-Reformation period.

Virgin Mary with the Child Jesus

Medieval traditions that carried forward.

Some medieval traditions continued into the early modern period in Spain. Devotion to the Virgin Mary, considered by many Christians to be the last avenue of hope for access to heaven, remained strong in Catholic Spain and its colonies throughout the Siglo de Oro (Spanish Golden Age).

Teresa of Avila

Teresa was an avid writer, documenting her daily life and thoughts.

This statue of the famous patron saint of Spain is unique because of what is missing. Her hands are positioned in such a way that her left hand may have been holding a pen and her right hand parchment. Writing was a critical part of Santa Teresa’s life, exhibited through her many letters and personal journals, so she would naturally be depicted with the necessary materials in hand.

Blessed Teresa of the Most Holy Mother of God of Mount Carmel

Teresa’s visions…

This engraving is part of a series that illustrates key religious experiences from Teresa of Avila’s autobiography. Teresa is seen casting away demonic figures, one of her many religious victories. Notice how this engraving’s numerous details promote her saintly nature. Throughout her life, Teresa had many visions of angels and demons, often attributed to her holiness. Her visions and mystic practices, like solitary prayer, attracted the attention of the Inquisition. Although Teresa was later acquitted, the Inquisition censured her autobiography because she, as a woman, did not have the authority to instruct others in religious doctrine.

Letters of Saint Teresa of Ávila Cartas de la Santa Madre Teresa de Jesus

“I beseech your Majesty, then, for the love of God, not to allow such scandalous charges to be made…”

This collected volume demonstrates Saint Teresa’s epistolary contact with important political and religious figures. In this printed copy of a letter, Saint Teresa implores Philip II to intervene in a case in which she believes that a group of nuns and a priest have been unjustly accused. Such interventions demonstrate how Saint Teresa worked to protect others within her order from the same sort of Inquisitorial repression she endured.

Plants of the Golden Age

Because medical practice relied on herbal remedies, the Spanish eagerly sought out new medicinal plants in the Americas. The Spanish viewed indigenous American plants through the same stereotype—the “inferior native”—used to justify imperialism. For example, they perceived the tomato as poisonous since it belonged to the nightshade family. They worried that it could be used as an aphrodisiac, a practice associated with the sin of lust. Some plants, such as tobacco and cocoa, became luxury goods in Europe. Others, such as tomatoes and corn, took longer to gain acceptance, even though they have now become staple foods in many countries. Contact with new species of plants caused Europeans to re-examine their understanding of plant life and expand upon previous scientific classifications. Many native plants of the Americas, such as the willow tree (from which aspirin is derived), are key components of modern medicine.

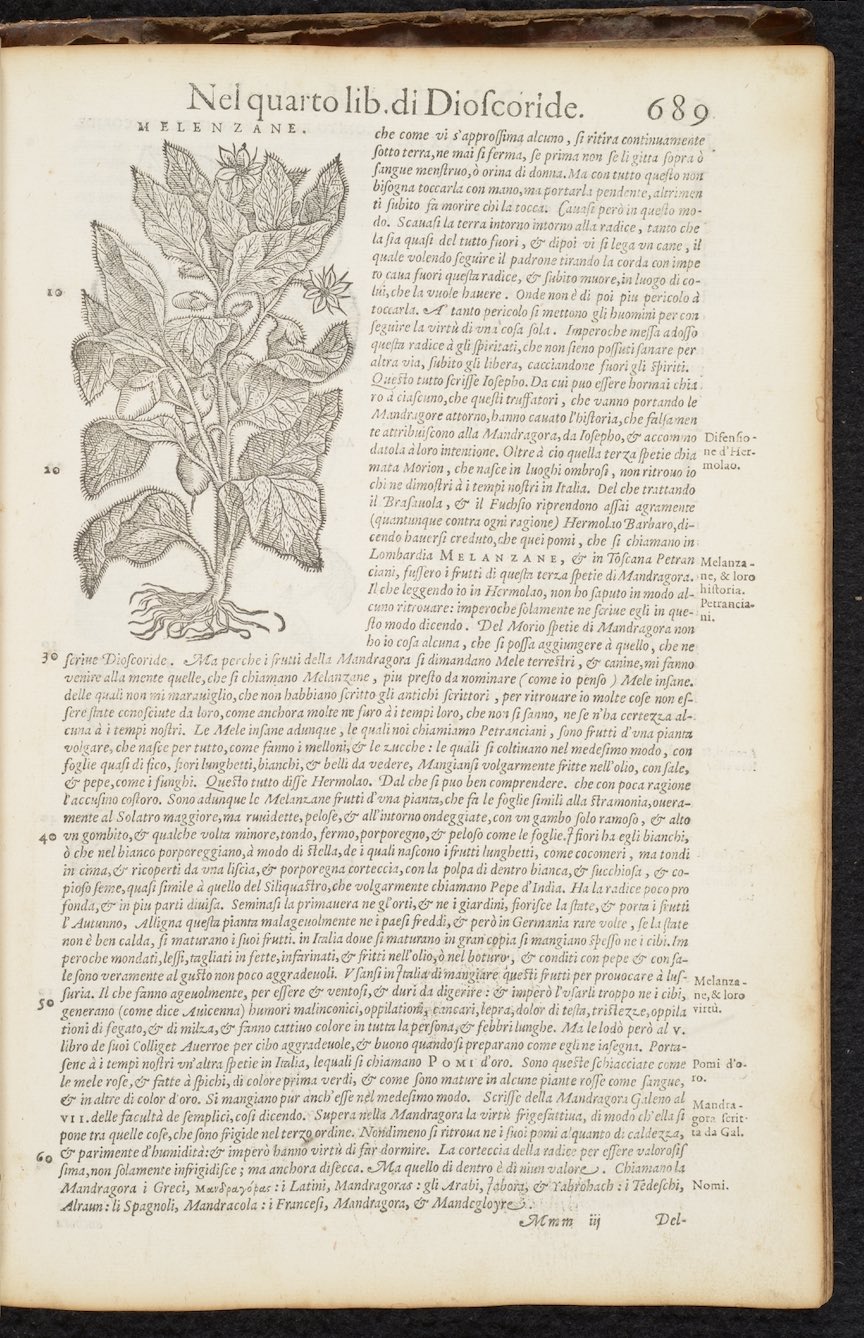

Image of an Eggplant

Mysterious and heretical fruit.

Tomatoes, native to the Americas, were associated with the eggplant, part of the nightshade family (a group of plants believed to possess aphrodisiacal qualities). Because aphrodisiacs were associated with images of the devil, these plants were viewed with suspicion and disdain. Eggplants were also associated with Islamic culture, which, because of Spain’s recent past, prompted further mistrust among the Spanish toward the tomato plant.

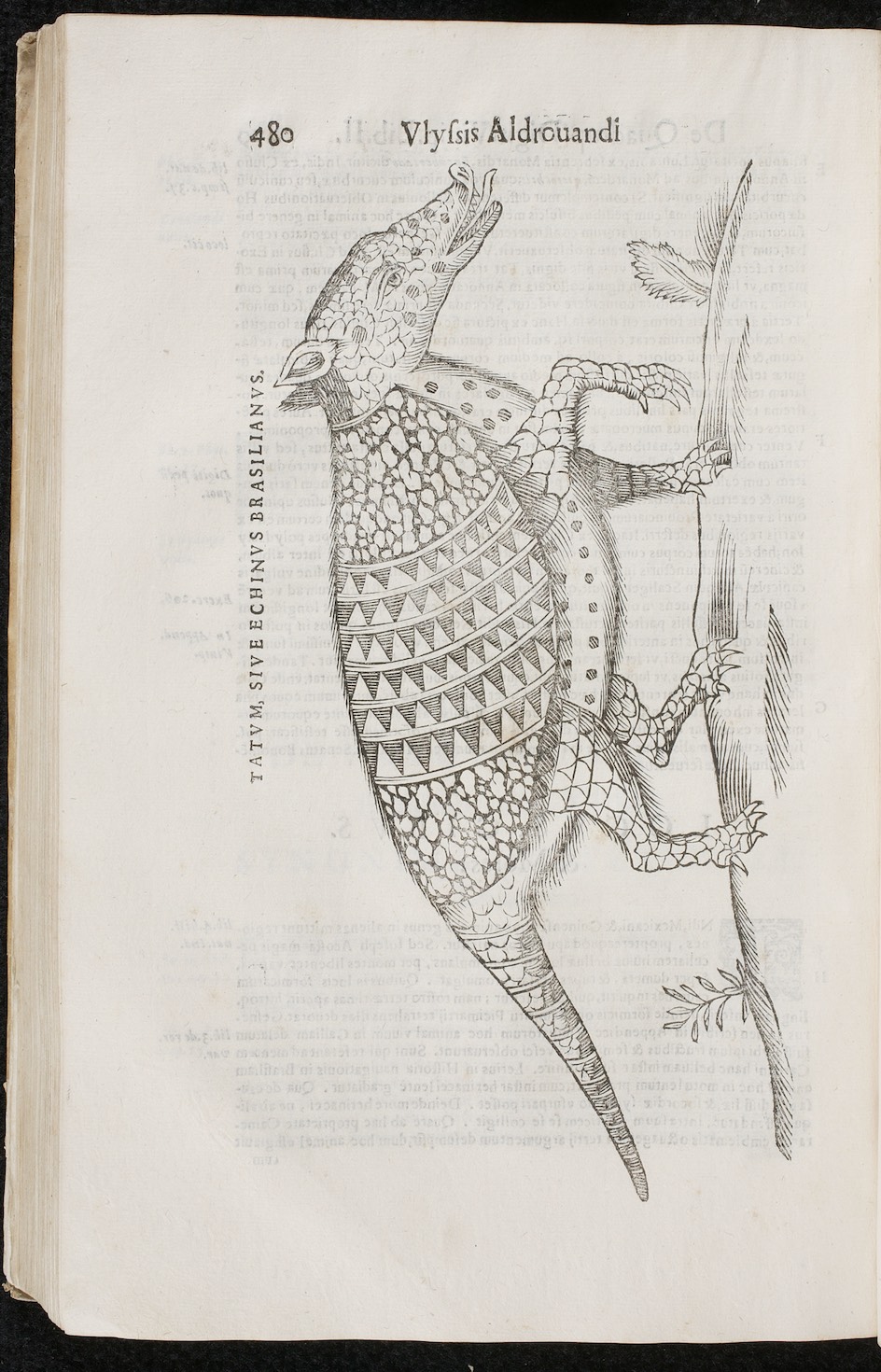

De Quadrupedibus (On Quadrupeds)

Fantastical embellishments.

Although Ulysse Aldrovandi never traveled to the Americas, he read the works of natural historians who had and used these accounts to incorporate new findings into existing bodies of knowledge. Many of the creatures of the Americas, such as the armadillo depicted here, must have seemed fantastic to the European reader. The creature’s intricate patterns, rather than scales, remind us that Aldrovandi utilized written reports as the basis of his illustrations, such that many of the creatures are not depicted in a realistic fashion.

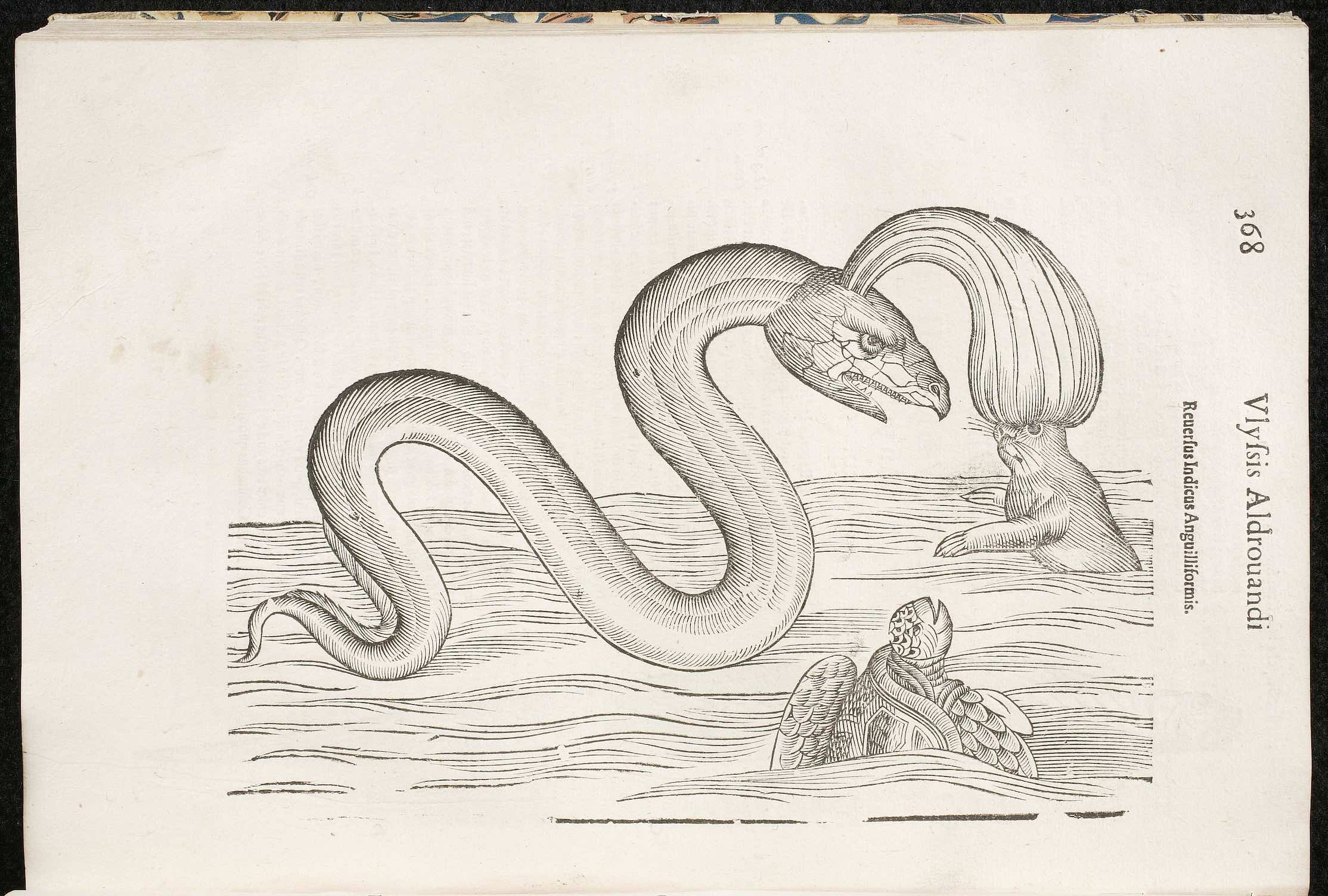

On Fish in Five Books and On Whales in One Book

Sea monsters.

Prior to the Scientific Revolution, understanding of animal life was based not only on observation, but also classical knowledge and travel narratives. Since illustrations of creatures that Europeans would not have directly observed, such as sea life, derived from written descriptions from sailors, they often appear unrealistic to the modern observer. This sea monster may seem mythical to a modern observer, but to a contemporary observer it would seem no less strange than other exotic creatures, such as lions or llamas.

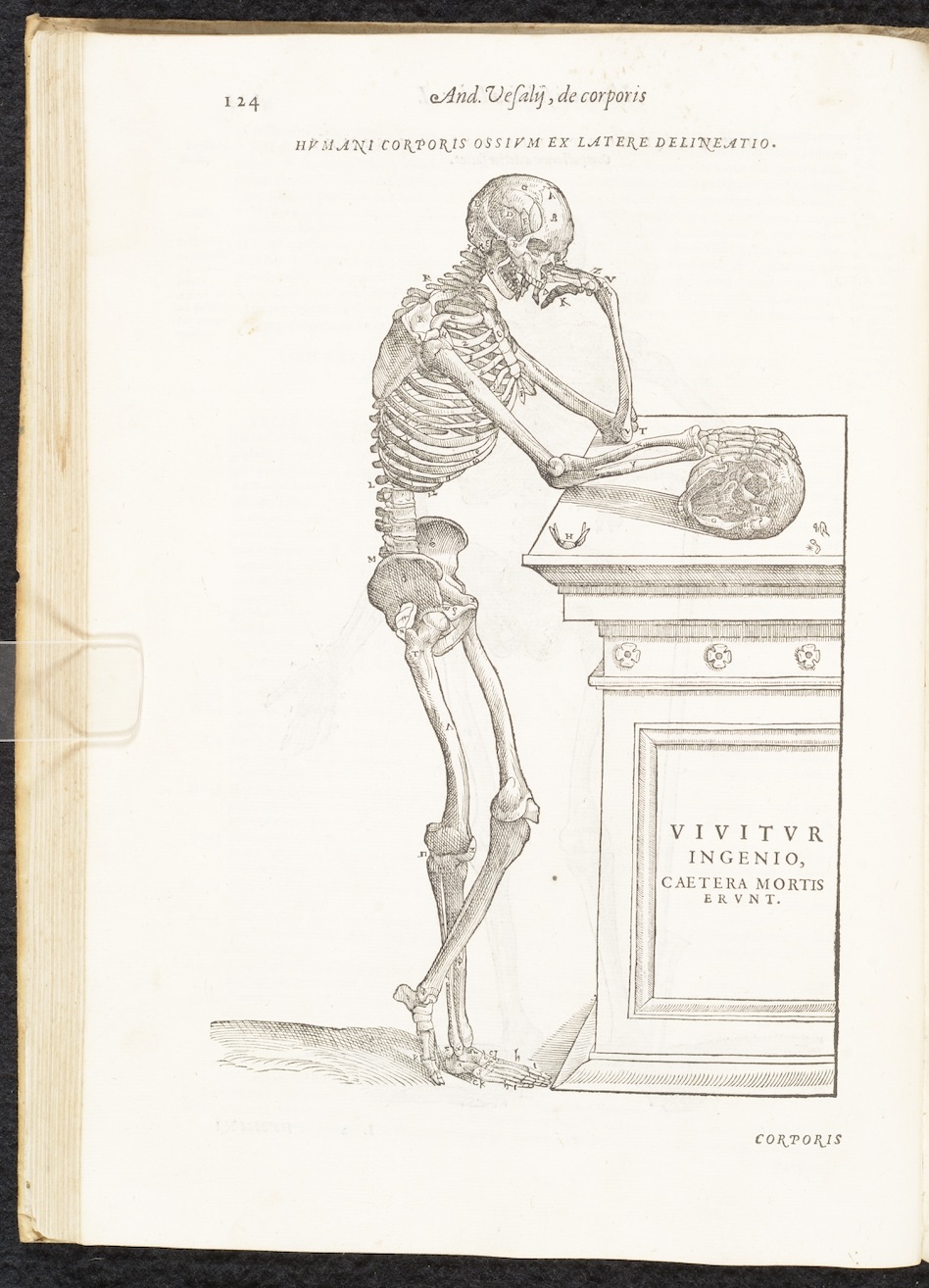

On the Structure of the Human Body in Seven Books

Looking inward.

Never had the inner workings of the human body been so thoroughly documented before Andreas Vesalius’ De humani corporis fabrica. Many of the book’s woodcuts depict actual human dissections performed by Vesalius, who had a steady supply of cadavers from executed criminals. De humani corporis fabrica has been heralded as the greatest medical book of the 16th century and was frequently reprinted during that time.

Towards Modernity

In the three centuries since its Golden Age, Spain underwent monumental cultural shifts as it moved from an absolute monarchy to a republic, then to a dictatorship, and lastly to a constitutional monarchy and member of the European Union. Much like the American Revolutionary period, the Golden Age serves as a historical symbol of national character and as a tourist attraction. However, cruel policies and actions—like those that contributed to Spain’s Black Legend—created a backlash that pushed the full story of Spain into the shadows of history.

Spain’s influence during the Renaissance should not go unnoticed. Its scientific and artistic contributions laid a foundation for scholars to continue learning for centuries to come.

There are still strong ties in Spain to its Golden Age history, often referencing it as a time of defining identity. One example of this is the modern-day Spanish Coat of Arms, which is reminiscent of the imagery and themes found in the Catholic Monarchs’ Coat of Arms from 1492.

Humankind struggles to understand our place in a rapidly changing world, just as early modern Spaniards once did. Throughout the United States, Spain, and much of the world, conflict surrounding immigration, imperialism, and identity challenge our ability to live peacefully. Emerging from the shadows of history, the story of Spain’s Golden Age shows us that modern issues of identity, the ‘other,’ and religion’s place in society are not confined to the time period in which we live.

Curator(s)

Abbey Witham (CSB+SJU class of 2021)

Credits

Curators

Abbey Witham (CSB+SJU class of 2021); Dr. Emily Kufner; and the members of the CSB+SJU 16th and 17th-century Spanish Literature class, spring semester 2020.

Credits

Special thanks to Dr. Matthew Z. Heintzelman, who worked side by side with the CSB+SJU class and assisted them in their research; Wayne Torborg and Mary Hoppe, who provided the digital photos throughout the exhibition; and to John Meyerhofer and Margaret Bresnahan, who prepared the online version.

spanish golden age, spain golden age