France And The Order Of Saint John Of Jerusalem

France and the Order of Saint John of Jerusalem

From Ancien Régime to Revolutionary Europe

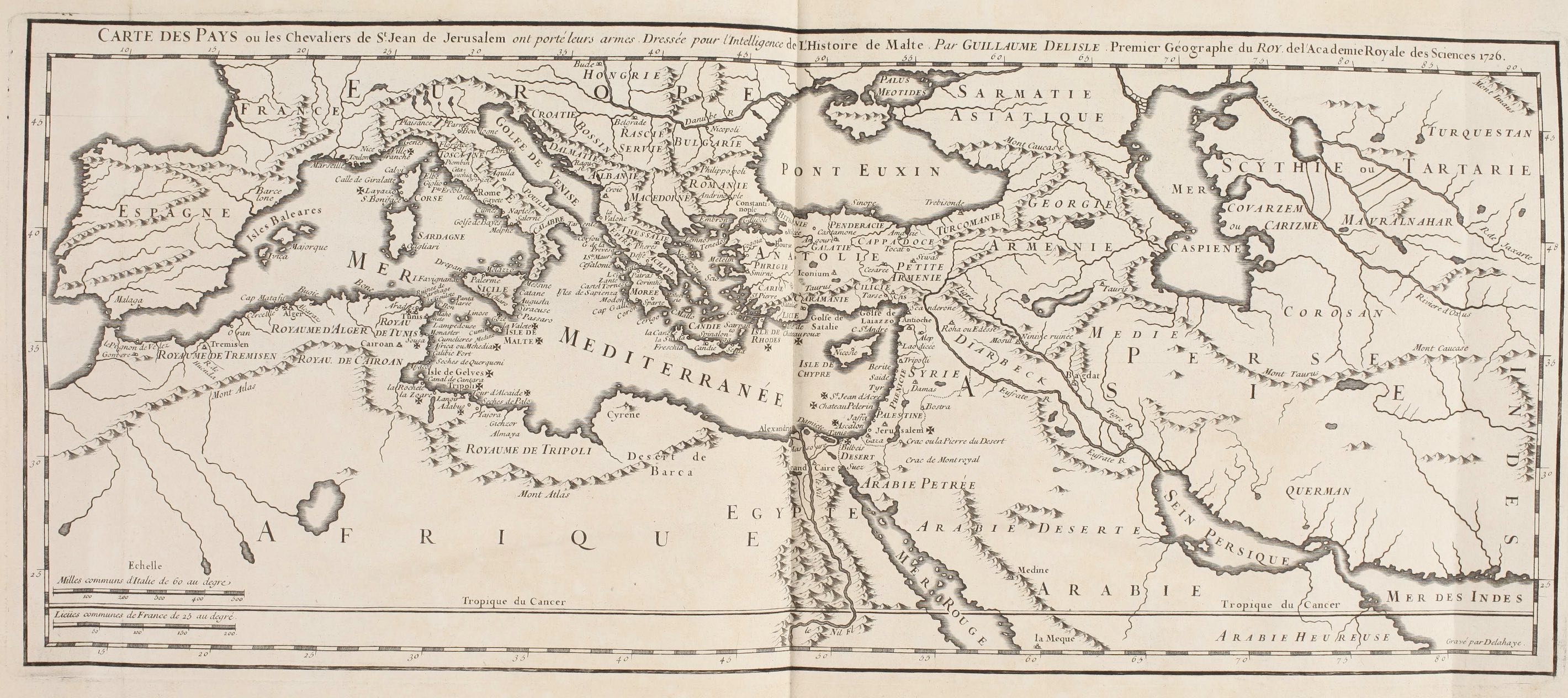

“France and the Order of Saint John of Jerusalem: From the Ancien Régime to Revolutionary Europe” introduces the world of the Order of Saint John of Jerusalem in France and Malta from the mid-17th century through the French Revolution and Napoleonic era. The exhibition highlights the daily lives of the French knights and sisters who joined the Order of Saint John and includes items from the French Revolution and Napoleon's conquest of Malta in 1798 narrating the consequences of revolutionary Europe for the Order and its members.

The Origins of the Order of Saint John of Jerusalem in France

Frenchmen who traveled to Jerusalem as part of the First Crusade became some of the earliest members of the Order of Saint John of Jerusalem. French knights, and later, sisters and chaplains, were organized into three langues, or administrative units, in France. This was largely to account for the different legal customs and regional dialects among the members. Their history became the subject of several works by French historians during the Middle Ages and early modern Europe.

Vertot, Rene Aubert de. History of the Knights of Malta. 2 volumes. London: Printed for G. Strahan, 1728.

Origins of the Order of Saint John of Jerusalem

The Order of Saint John of Jerusalem originated from a group of non-professed religious people who operated a hospice for pilgrims established in Jerusalem in the 11th century by Amalfi merchants. After the capture of Jerusalem in 1099, the new religious order that emerged from the hospice quickly attracted French members and benefactors to support its mission. The first century was dominated by French Grand Masters, who transformed the order into a military religious order whose influence extended across the Mediterranean.

![Atlas de toutes les parties connues du globe terrestre. [Amsterdam]: Evert van Harrevelt, 1780.](../../../assets/img/exhibitions/france-and-the-order-of-saint-john-of-jerusalem/1_2_HMML_00560_001.jpg)

Atlas de toutes les parties connues du globe terrestre. [Amsterdam]: Evert van Harrevelt, 1780.

The French and the Order of Saint John of Jerusalem

French membership in the Order of Saint John of Jerusalem grew rapidly in the 12th and 13th centuries. Men and women came from various regions of France with different customs and languages. The Order of Saint John divided France into three administrative units, or langues, reflecting regional dialects and legal customs. The north, centered on Paris, was called the Langue de France, where the “Oïl” dialects dominated. The Langue de Provence (“Oc” or Occitan dialects) was located in the southwest, and the Langue de Auvergne (Oïl dialect), located between the Langue of France and Langue of Provence from the Atlantic to the border of Switzerland.

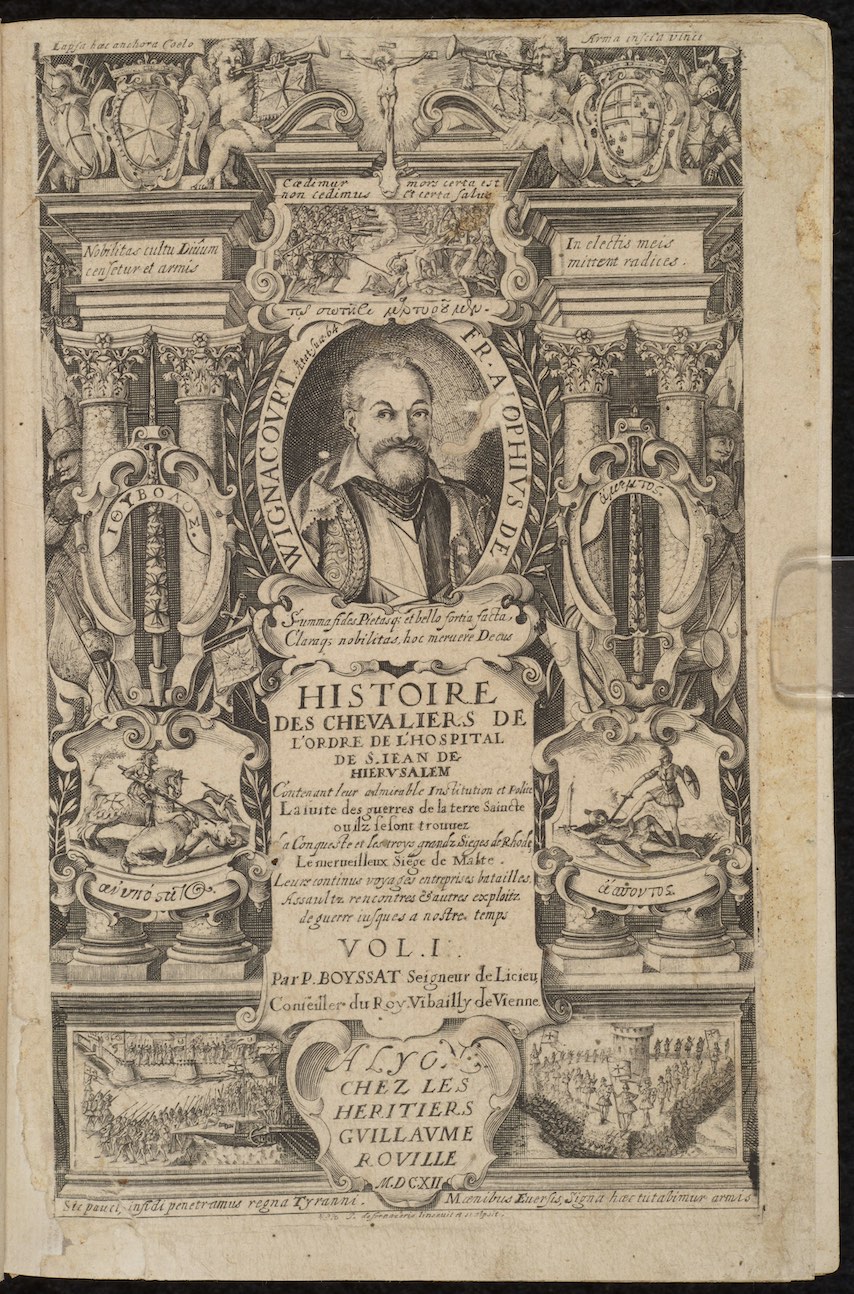

Bosio, Giacomo and Pierre de Boissot. Histoire des chevaliers de l’Ordre de l’Hospital de S. Jean de Hierusalem. Lyon: Héritiers Guillaume Rouille, 1612.

Early French history of the Order of Saint John of Jerusalem

Pierre de Boissat, a French noble and administrator in Vienne, lived in the heartland of the Langue of Auvergne. His translation and continuation of Giacomo Bosio's Dell'istoria della sacra religione et illustrissima militia di San Giouanni Gierosolimitano offered French knights of the Order of Saint John an early comprehensive history of their religious order. Boissat's translation included the Order’s statutes, providing a resource to compare the Order's legislation in the context of its history.

Bouhours, Dominique. Histoire de Pierre d’Aubusson Grand-Maistre de Rhodes. 3rd edition. The Hauge: Gerard Block, 1739.

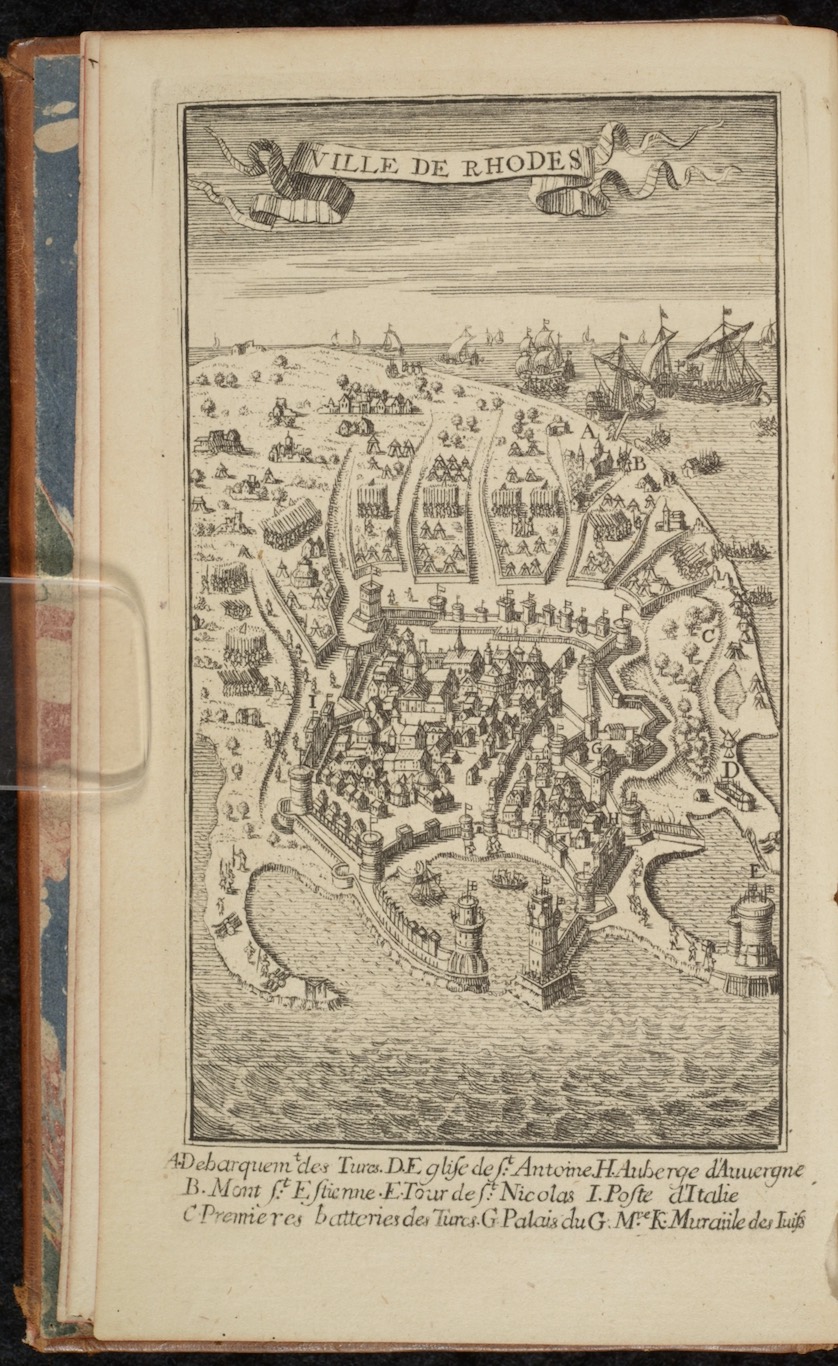

French Grand Master Pierre d’Abusson as a model military leader

Dominique Bouhours’s biography of Pierre d’Aubusson (1423-1503) depicted the French Grand Master as the model Catholic military leader for his defense of Rhodes against the Ottomans in 1480. Bouhours’ biography likened Pierre d’Aubusson’s military prowess to that of his relative, François d’Aubusson de la Feuillade, Duke of Roannais, who fought against the Ottomans in 1664 at Saint Gotthard, and again in Crete in 1668.

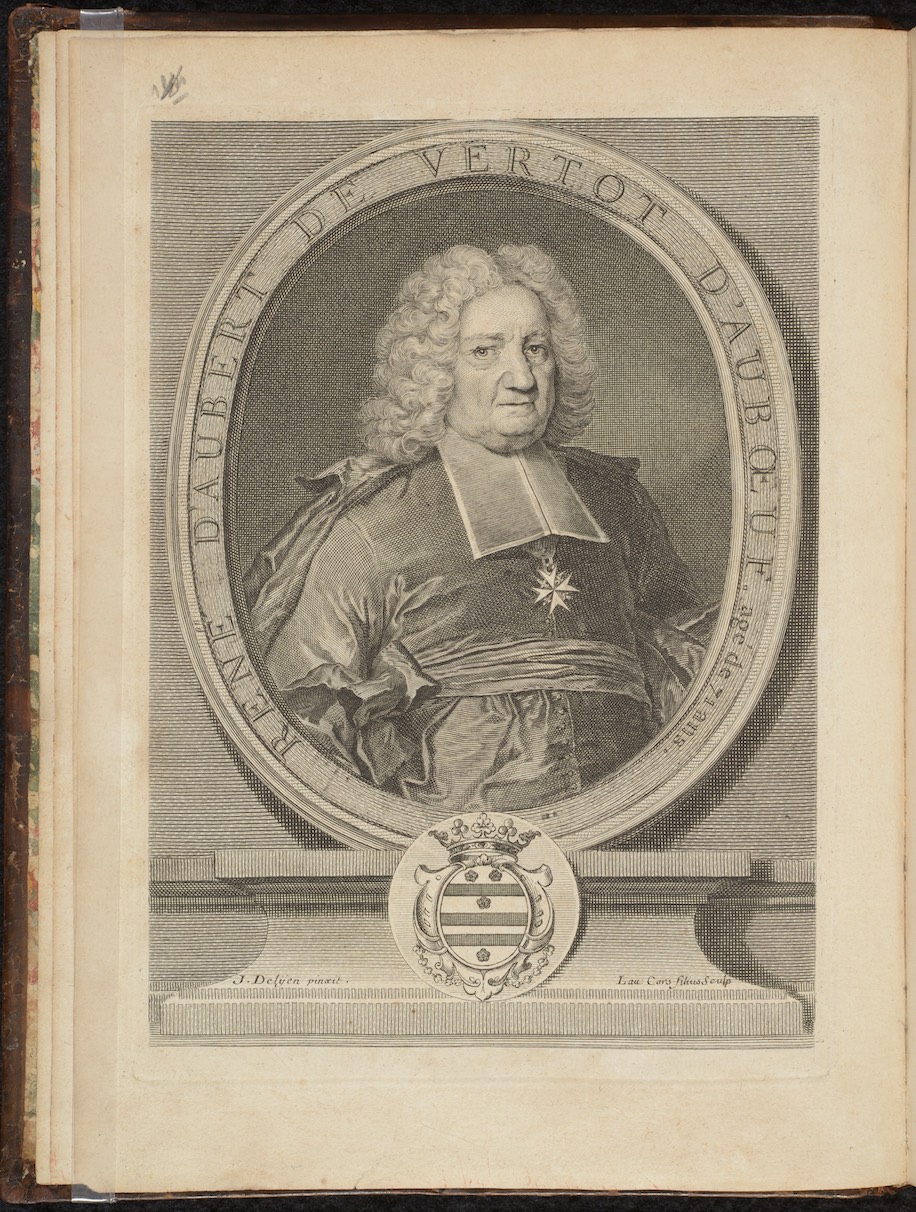

Aubert de Vertot, Réne. Histoire de chevaliers hospitaliers de S. Jean de Jerusalem. Paris: Jacques Rollin, Jacques Quillau, Jean Desaint, 1726.

A revised and controversial history of the Order of Saint John of Jerusalem

Fra Réne Aubert de Vertot’s history of the Order of Saint John fell victim to the contradictions of 18th-century France. His accessible, didactic style immediately drew praise. However, his work was condemned by the Order of Saint John and the Catholic Church for its often disdainful reinterpretation of the Order's historical persons and events. This critique resulted from the influence of the French Enlightenment on historical criticism, and the change in literary culture that rejected interpretation based solely on tradition.

Knights and Sisters of the Order of Saint John of Jerusalem

Men and women joined the Order of Saint John of Jerusalem, but the first hurdle was gaining entry into the Order. To this end, knights would submit elaborate legal documents to prove their nobility. Chaplains and sergeants of arms needed to document their good standing and lineage, while leading women in the community needed to provide evidence of their rank and ability to give a dowry. Once members, men and women followed the rule of the Order, which guided their way of life and death.

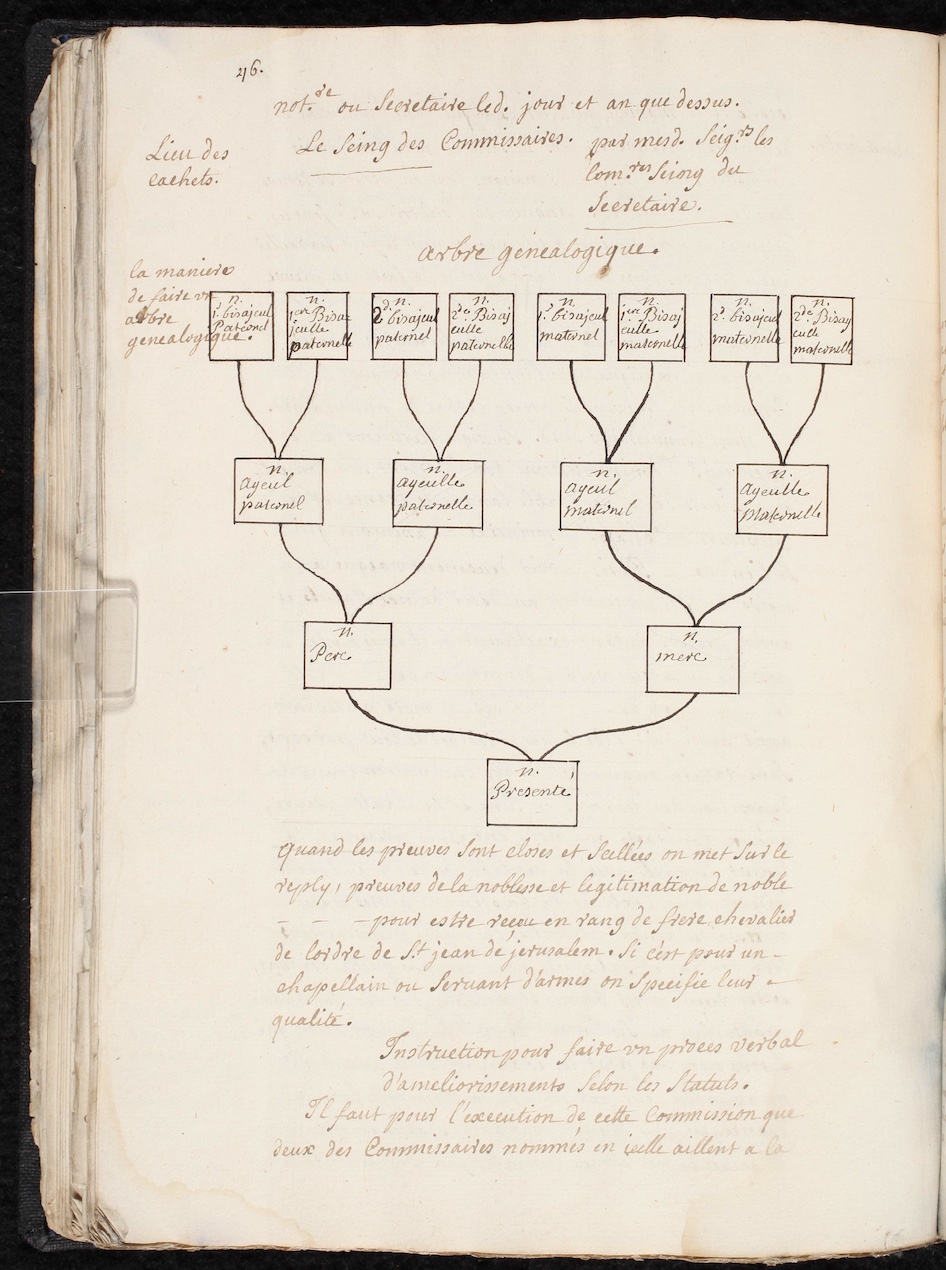

Instruction pour faire les preuves tant de chevaliers de justice, servants d’armes et frères chapelains. France, 18th century.

A guide for admission into the Order of Saint John of Jerusalem

French nobles who wished to join the Order of Saint John of Jerusalem prepared an extensive dossier, or preuve (proof), of their noble lineage to join the Order. Strict guidelines set by the langue and the central convent were used to validate a postulant’s nobility through a detailed genealogy and rigorous legal review. Becoming a knight in turn validated the family’s noble lineage and improved its reputation among peers. Dispensations granted by the papacy were possible, but not common.

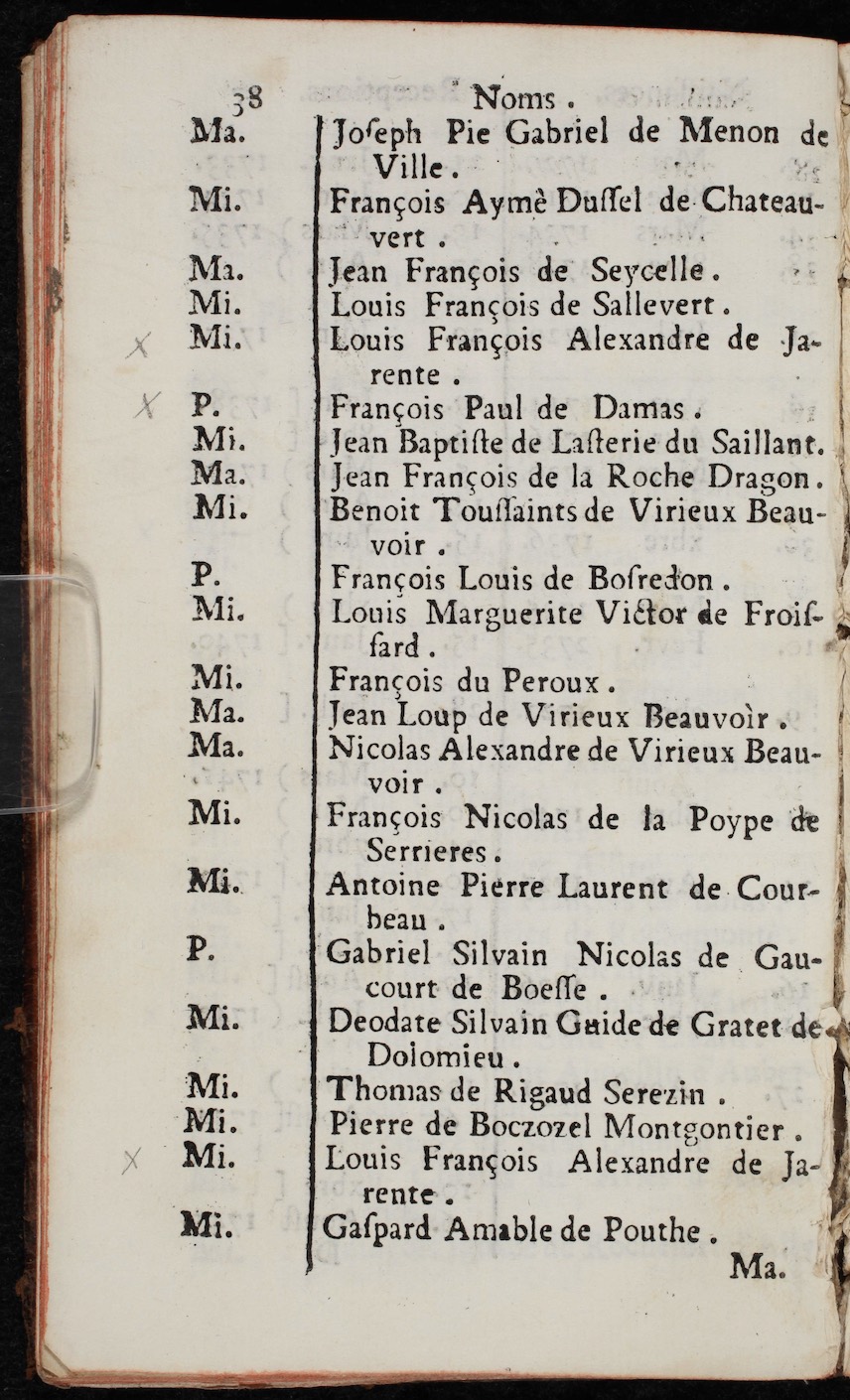

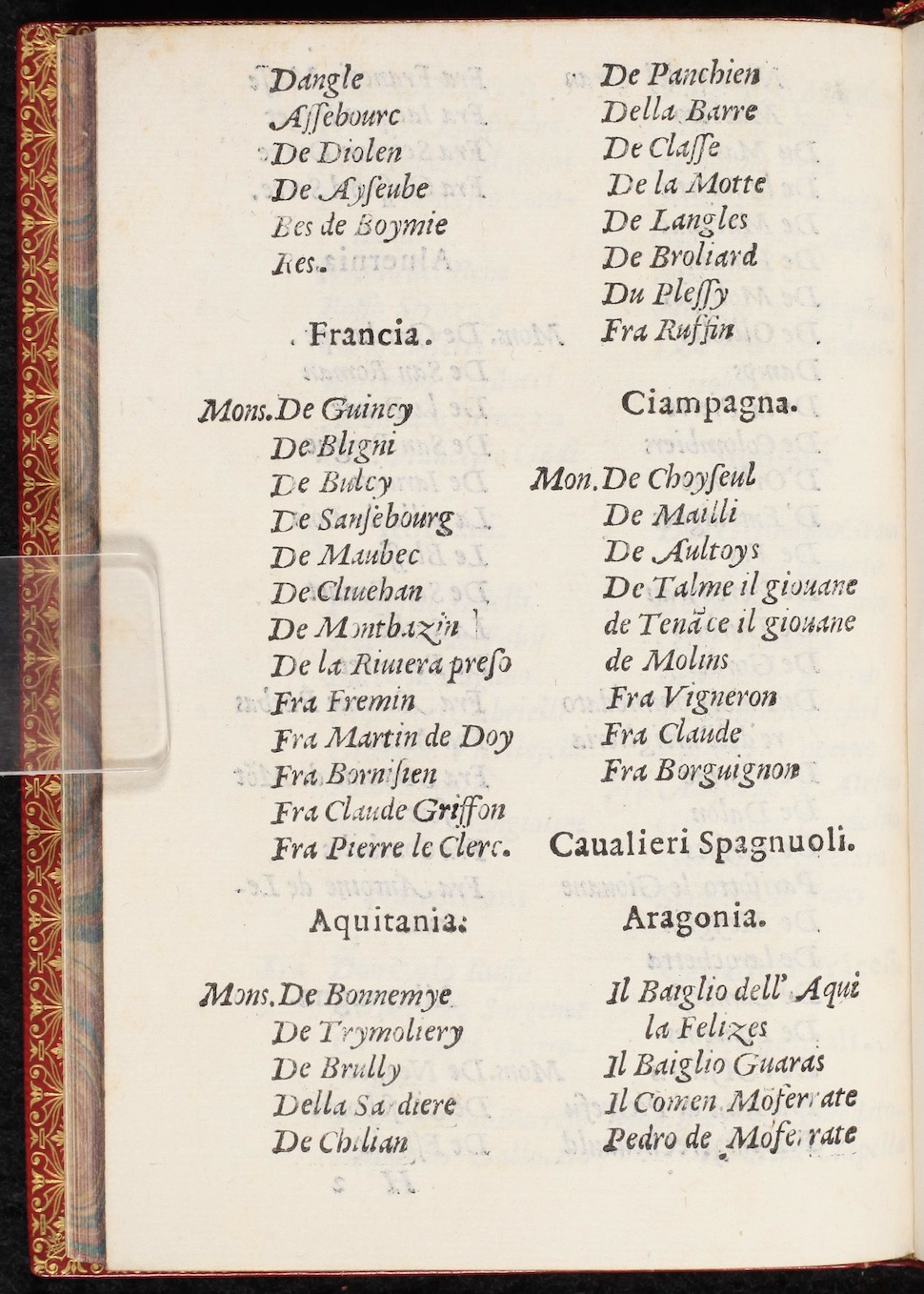

Listes des messieurs les chevaliers des trois vénérables langues de Provence, Auvergne, et France, Faittes en 1761. Malta: Niccolò Capaci, 1761.

A list of the French knights of the Order of Saint John of Jerusalem

Being admitted into the Order of Saint John of Jerusalem brought French nobles additional privileges as members of a military religious order. Elaborate lists of the Order’s members were created to track the date of admission for each knight to determine rank, or ancianitas. Rank was determined by when a person entered and not the age of the knight or the noble house in which they were born. Distinctions such as entering as a minor or serving as a page to the Grand Master as a youth increased one’s position within the Order.

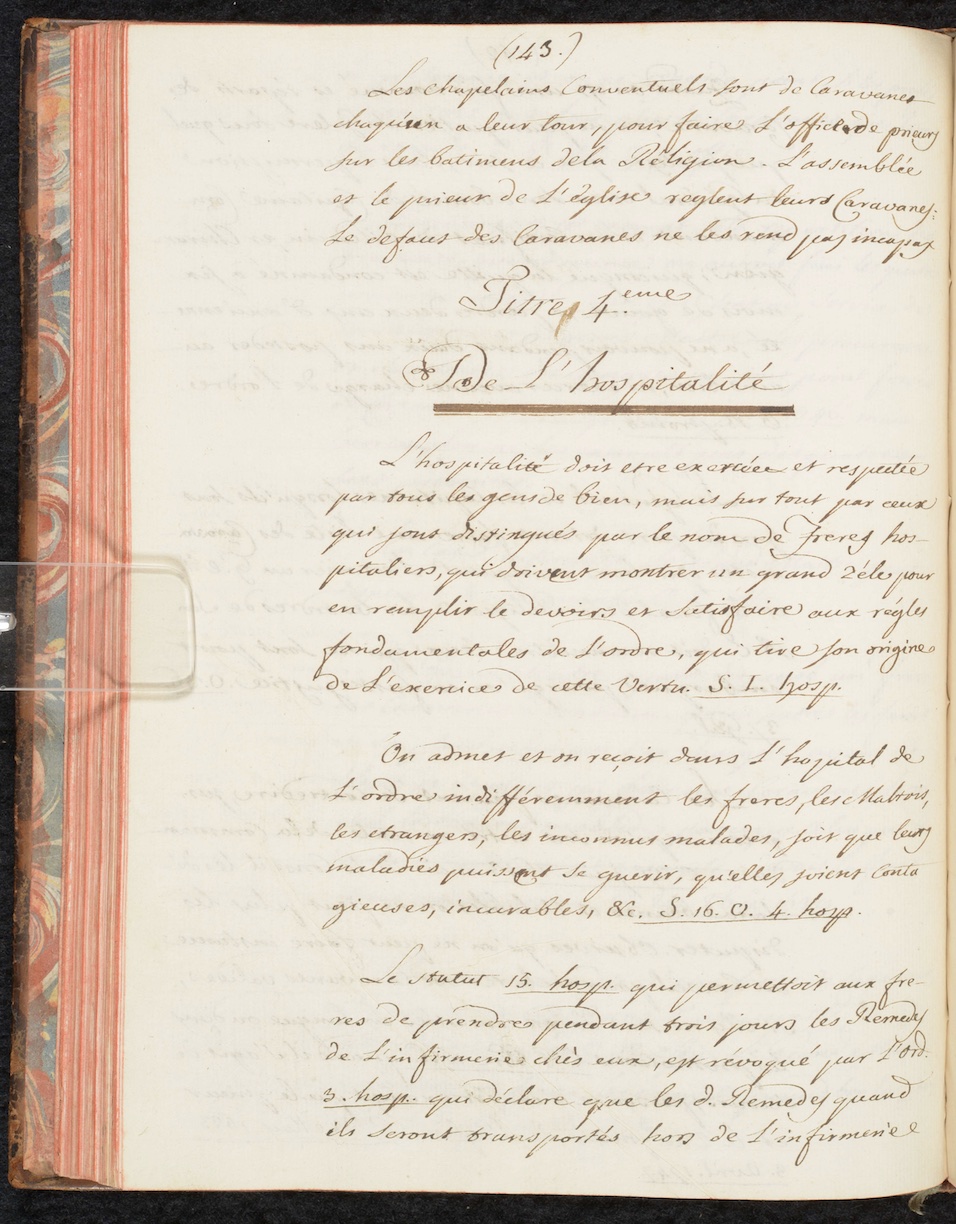

Caravita, Giovanni. Statuts de l’Ordre de Saint Jean de Jérusalem commentés par le Prieur Caravita et traduits de l’Italien. France, 1756.

Commentary on the statutes of the Order of Saint John

French knights, like their brethren from other parts of Europe, were governed by the rule and statutes of the Order of Saint John of Jerusalem. These statues developed over centuries, and like most constitutions, were frequently disputed as much as they were followed. French knights translated commentaries by the Order’s legal scholars, such as Giovanni Caravita, to navigate the statutes governing elections and admittance, as well as the practice of hospital care and hospitality that were central to the Order’s identity.

Regles et constitutions des religievses Hospitalières de l’Ordre Sainct Iean de Ierusalem. Toulouse: François Boude, 1644.

Rules for the lives of the Sisters of the Order of Saint John of Jerusalem

French sisters of the Order of Saint John of Jerusalem followed the same statutes that governed the male members of the Order. The sisters, however, also had their own rules befitting a community of women leading a cloistered life. Translations of the rule into French were provided to help govern the community, though essential parts, like the letter Grand Master Giovanni Paolo Lascaris (1560-1657), were provided in the original Latin (with French translation) of their obedience to the Grand Master of the Order of Saint John.

Pietro Gentile di Vendôme. Della Historia di Malta, et successo della guerra seguita tra quei Religiosissimi cavalieri. Bologna: Giovanni Girolamo Rossi, 1566.

A list of French knights who died at the Great Siege of Malta in 1565

The Order of Saint John’s victory in the Great Siege of Malta in 1565 was a generational event that defined the Order’s importance for defending Christendom against enemies of the faith. The remarkable victory against the Ottomans was set against the significant losses experienced by the Knights and Maltese in the defense of the island. French knights were listed alongside their brethren according to their priory, here showing Fra Trilleu de Montbazon with twelve other knights in the Priory of France, part of the Langue de France.

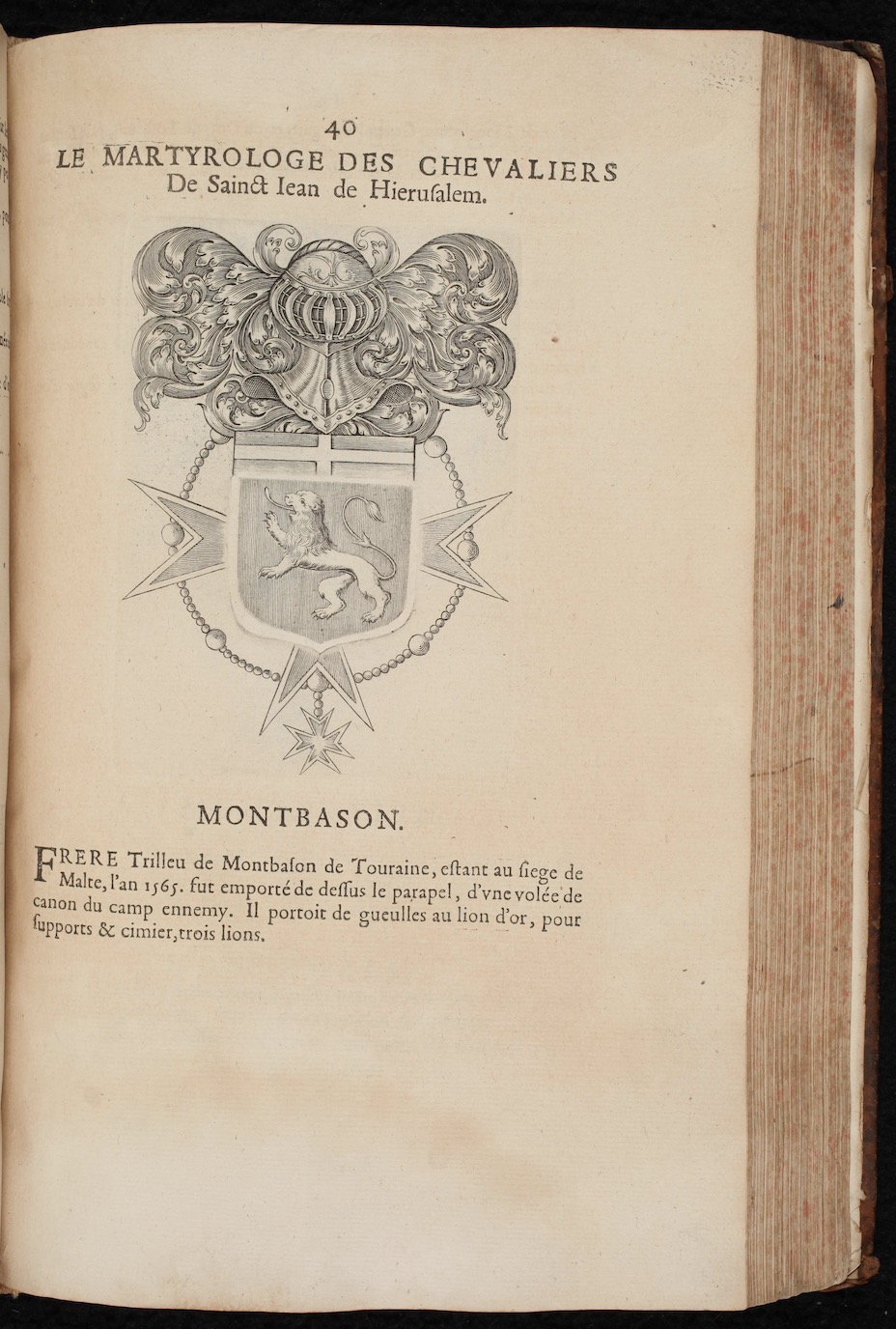

Mattheiu de Goussancourt. Le Martyrologe des chevaliers de S. Iean de Hiervsalem dits de Malthe. Paris: Simon Piget, 1654.

Fra Trilleu de Montbazon, martyr of the Great Siege of 1565

Mattheiu de Goussancourt’s biographical study of the martyrs of the Order of Saint John of Jerusalem exemplifies how the Order venerated their brethren who died while fighting to defend Christendom as martyrs. Women whose personal asceticism and devotion were elevated to the same status, since the practice of monastic life was seen as a spiritual martyrdom in the eyes of the Church. Remembrance of the dead and prayers for their intercession remained a core part of Hospitaller spiritual life in the Ancien régime.

Angoulême, Charles de Valois, duc d'. Correspondence relating to the Treaty of Ulm, 1620. France, ca. 1620

The Grand Prior of France and Diplomacy in Europe

Fra Charles de Valois, Duke of Angoulême, exemplified the French monarchy’s relationship to the Order of Saint John of Jerusalem on a personal level. With limited opportunities as the illegitimate son of King Charles IX and Marie Touchet, Fra Charles joined the Order, where he served as Grand Prior of the Langue de France. The king used Fra Charles’ diplomatic position as a member of the Order to negotiate the Treaty of Ulm of 1620, whereby the Protestant Union declared neutrality and ceased to support King Frederick I of Bohemia.

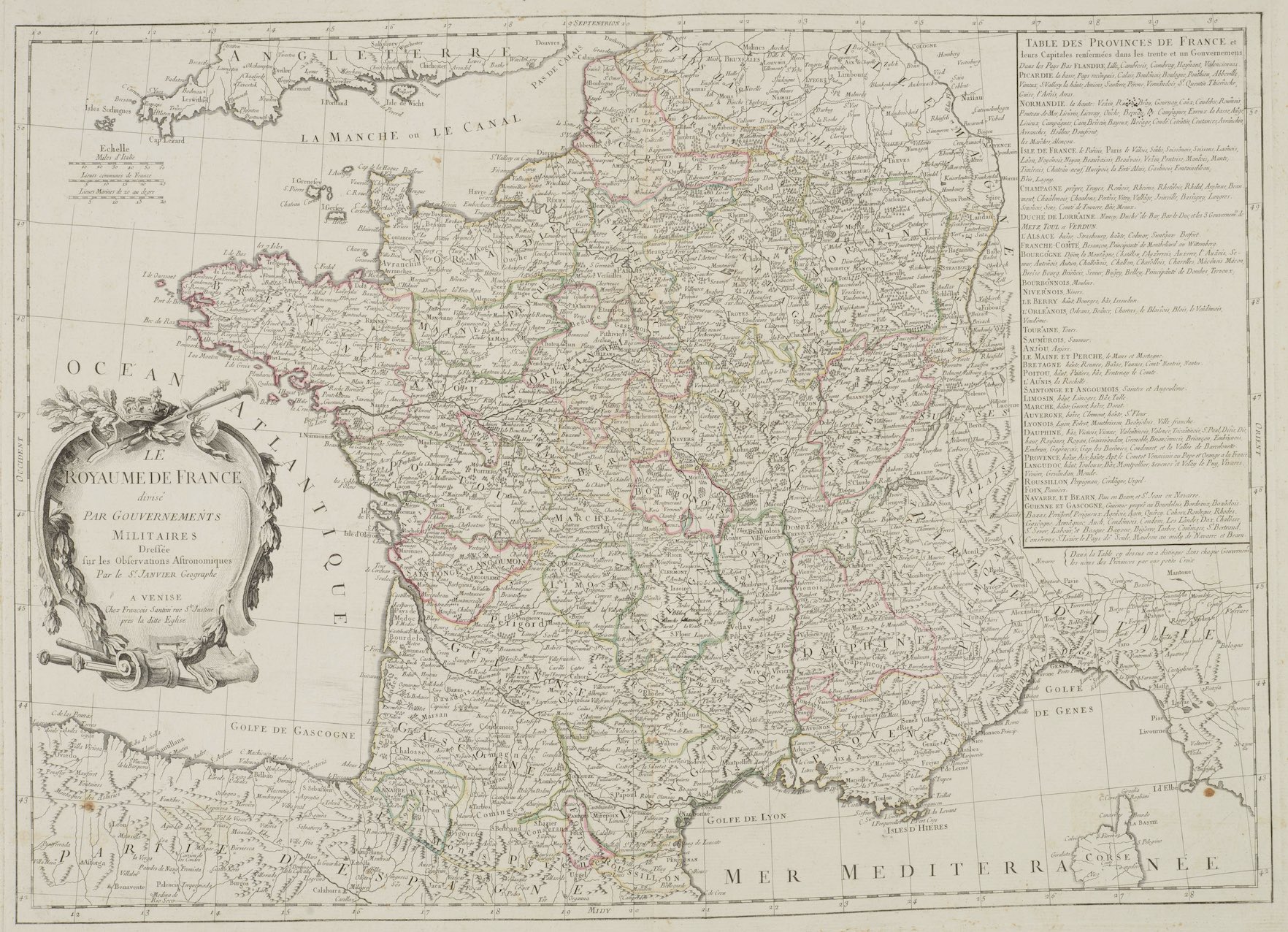

Santini, Paolo and Francesco Santini. Atlas universel, dressé sur les meilleures cartes modernes. Venice: Paolo Santini, 1776.

French knights in the service of the king

Francesco Santini’s map of the Kingdom of France divided into military districts reminds the reader of the importance placed on defending the realm against foreign invasion and domestic revolts during the Ancien régime. As nobles of France, members of the Order of Saint John held responsibilities to the defense of the realm as well as their family's property, often serving as military officers in the French army and navy while they served as officers in the military of the Order of Saint John of Jerusalem.

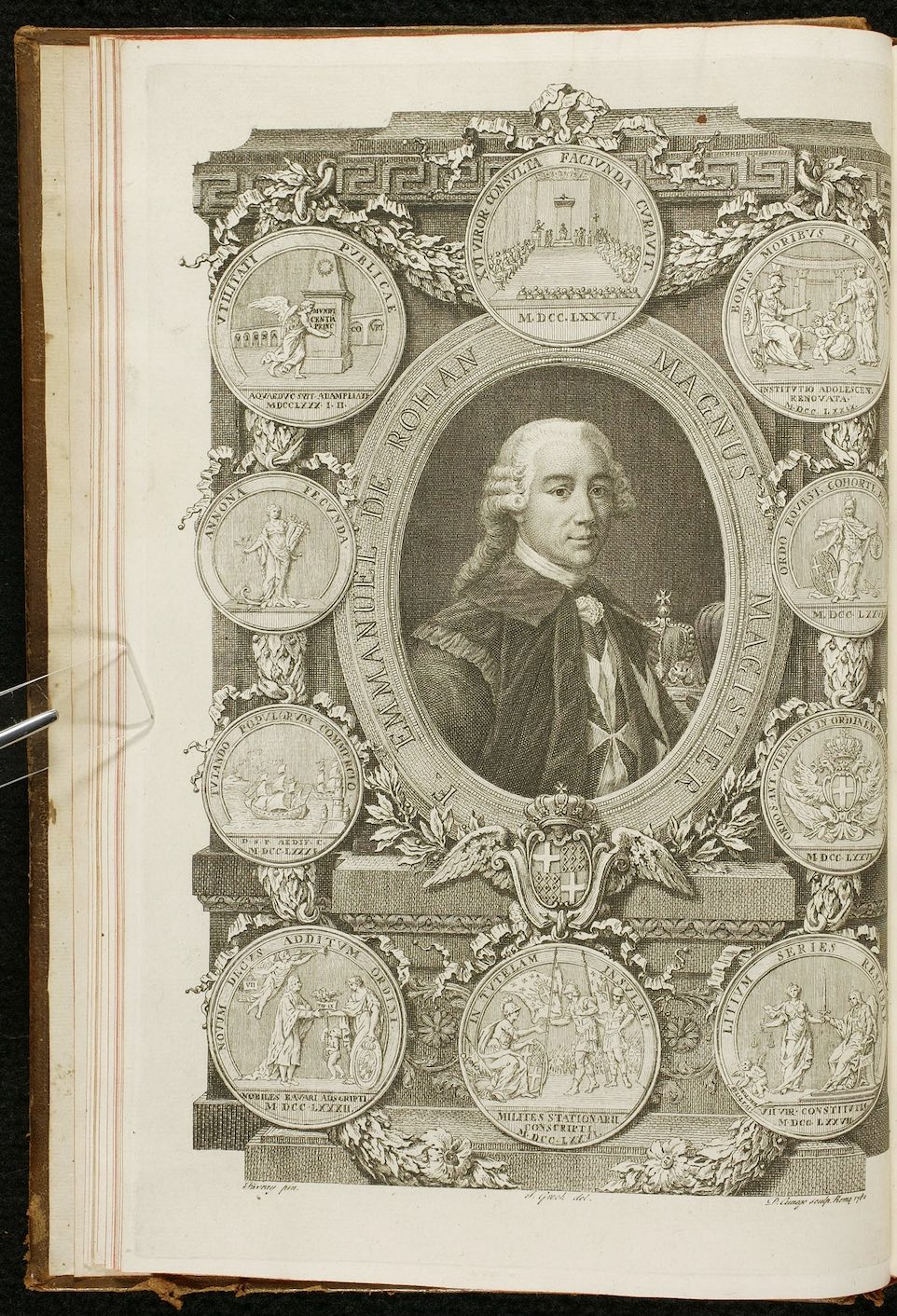

Codice del Sacro Militare Ordine Gerosolimitano. Malta: Giovanni Carlo Mallia, 1782.

Fra Emmanuel de Rohan-Polduc, prince du étranger and Grand Master

Grand Master Emmanuel de Rohan-Polduc followed a long tradition of the members of the extended royal family, whose second or third sons joined the Order of Saint John to advance their family’s position and reputation. Whether princes du sang (princes of the blood), or in the case of the House of Rohan, princes étrangers (foreign princes), obtaining the princely status of Grand Master formed part of the family’s efforts to validate their claims as descendants of a royal house, as in descendants of the Kings of Brittany.

Daily Life in the Order of Saint John

Life as members of the Order of Saint John included their religious practices, as well as the day-to-day activities of administering their communities. Knights and sisters were also poets, diplomats, scientists, and lawyers, who often defended the rights of the Order from challenges to their properties and status as members of a military religious order.

Office des Morts, sans Renvoy, A lʼUsage des Chevaliers de lʼOrdre de Malte. Paris: Veuve de Laurent d’Houry, 1741.

Office of the Dead for the Order of Saint John of Jerusalem

Prayers for the dead were an important part of the daily religious lives of the Order of Saint John of Jerusalem. Like other religious orders, the liturgical office was sung when a knight, sister, or chaplain died. The office was also performed throughout the year to pray for the souls of the deceased on the anniversary of their death, or feast days such as All Soul’s Day. Care for the sick and dying, extended to the afterlife, as the intercessory prayers benefitted the soul’s ascent into heaven.

Pouget, François-Aimé. Instructions sur les principaux devoirs des chevaliers de Malte. Paris: Nicolas Simart, 1712.

A religious primer for knights of the Order of Saint John of Jerusalem

The religious education in practice fell to the chaplains and older knights of the Order of Saint John of Jerusalem. Knights would travel to Malta when they joined, and upon completing their novitiate, would make vows of poverty, obedience, and chastity. Religious formation continued whether the knight stayed on the island or returned home. While the Order composed its own religious primers, theologians like Oratorian François-Aimé Pouget wrote on behalf of the Order’s members.

Boufflers, Stanislas-Jean de, Oeuvres du Chevalier de Boufflers. The Hague: Jacques Detune, 1781.

Poems and tales of travels by a knight of Saint Jean of Jerusalem

French knights of the Order of Saint John contributed to the scientific, literary, and artistic culture of Europe as nobles engaging in the arts and sciences. Stanislas-Jean de Boufflers used his position as a non-professed member of the Order to participate in the salons of Paris and engage in correspondence with members of the nobility. His collected works included poetry, epistolary travel narratives, and letters popular among French literary circles in the 18th century.

Pierre Privat de Fontanilles. La Maltiade ou l’Isle-Adam dernier grand-maître de Rhodes, et premier grand-maître de Malte. Poeme. Arles: Jacques Mesnier, 1770.

The Last Grand Master of Rhodes and First Grand Master of Malta

Pierre Privat de Fontanilles’s poem about French Grand Master Philippe Villiers L’Isle Adam was an homage to the Order of Saint John of Jerusalem, which educated him at the Hôtel de Malte in Toulouse under his uncle, Fra Jacques-François de Privat Fontanilles. The poem recounted the heroic deeds of French Grand Master Philippe Villiers L’Isle Adam, who led the knights at the Great Siege of Rhodes of 1520 and was the first Grand Master of the Order of Saint John of Jerusalem in Malta.

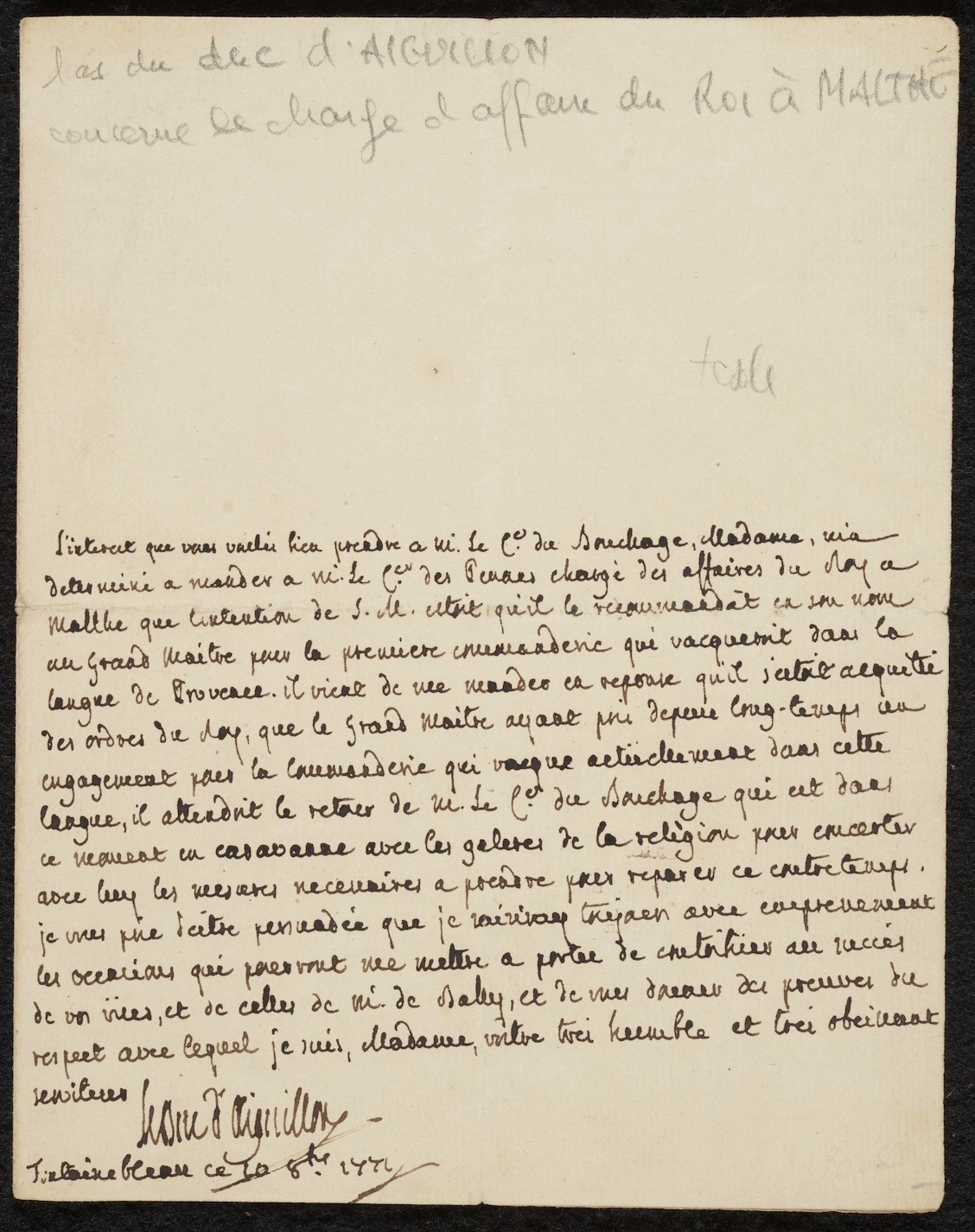

Letter of Emmanuel Armand de Vignerot du Plessis, Duke d’Aiguillon, to a certain “Madame”. Fontainebleau, 10 October 1771.

Correspondence to secure a French commandery

Patronage in the courts of Europe constituted a complex network of relationships through which aspirants sought the assistance of patrons to advance their careers. A letter from Emmanuel Armand de Vignerot du Plessis, Duke d’Aiguillon and Minister of Foreign Affairs, to a certain “Madame”, likely Madame du Barry, responding to her request that he influence Fra Toussaint de Vento des Pennes, Chargé d'affaires of France in Malta to entreat the Grand Master of the Order of Saint John of Jerusalem to provide Fra François Joseph de Gratet du Bouchage a vacant commandery in Provence.

France. Conseil d'État. Arrest du Conseil d'Estat du Roy qui ordonne qu'en payant par l'Ordre de Malthe la somme de quatre-vingt-dix mille livres. Paris: Imprimerie Royale, 1734.

Judgment concerning taxes of the Order of Saint John of Jerusalem

Judgment (arrêt) issued by the Conseil d'Estat du Roy that the payment of ninety thousand livres (pounds) by the Order of Saint John of Jerusalem to the royal treasury exempts all property belonging to the Order from the declaration of November 17, 1734, concerning the raising of the tax known as the tenth (la levée du dixieme). The edict was executed at the request of Frá Jean Jean-Jacques de Mesmes, ambassador extraordinary of the Order of Saint John of Jerusalem in France.

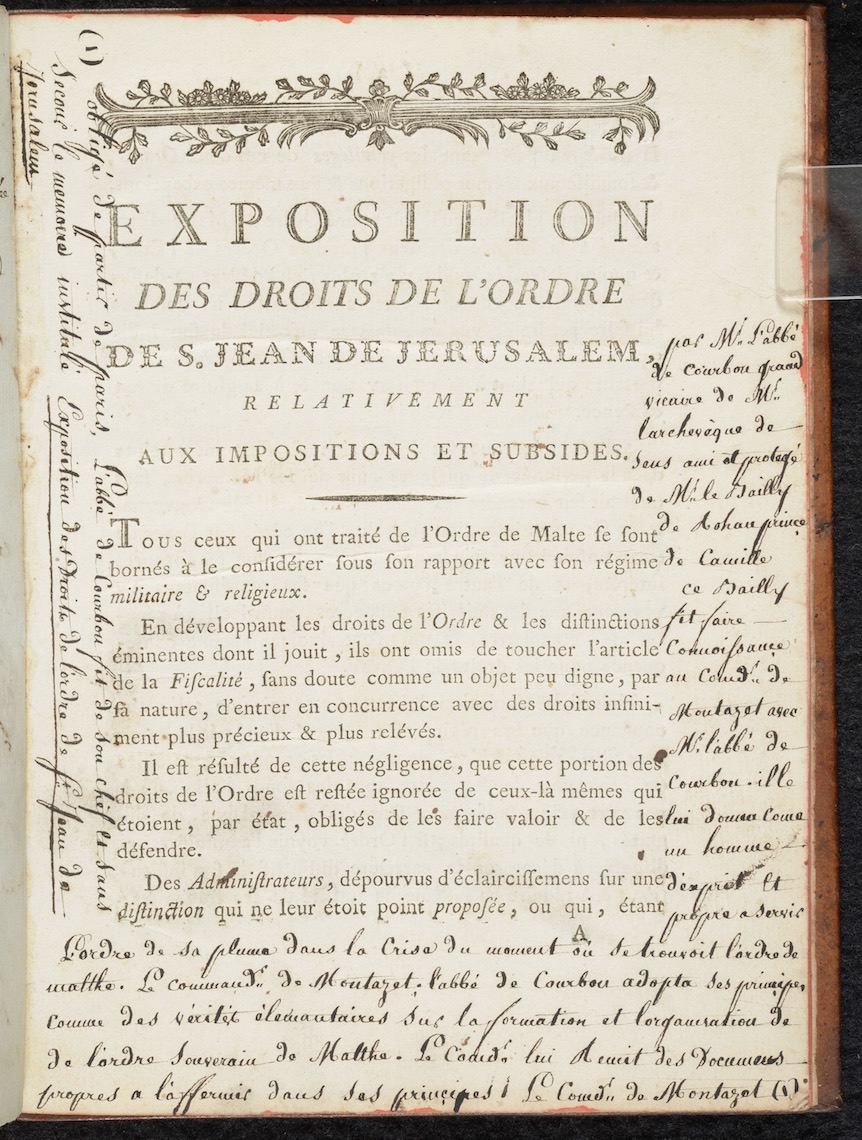

Courbon, Abbé de. Exposition des droits de l’Ordre de S. Jean de Jerusalem relativement aux impositions et subsides. France, circa 1789

Defending the rights of the Order of Saint John of Jerusalem

The Order of Saint John of Jerusalem called on its friends to defend the Order’s privileges when questioned by the French parliament or courts. The Abbé de Courbon, a protégé of Fra Eugène Hercule Camille de Rohan-Rochefort and friend of Fra Léon Malvin de Montazet, defended the Order’s rights and exemptions on the eve of the French Revolution, arguing that the Order’s privileges and exempt status were the foundation of its status as a military religious order, allowing it to defend the faith and serve the poor.

The Order of Saint John of Jerusalem during the Age of Revolution

The Order of Saint John fell victim to criticisms of their way of life by the thinkers and writers of the Enlightenment, who saw the knights and sisters as obsolete vestiges of the Middle Ages. Scandals, both fabricated and containing some truth, tarnished the image and reputation of the Order. This would eventually lead to its suppression in France, and later its expulsion from Malta by Napolean Bonaparte.

Mesmes, Jean-Jacques de. Memoire pour Monseiur l'ambassadeur de Malthe contre la damoiselle Prevot. Paris, 1726-1750

A knight’s accusations against a former lover

Memoir of Fra Jean-Jacques de Mesmes against the dancer, Mademoiselle Françoise Prévost. Originally published in 1726, the memoir, written in the third person, was intended to shame Frá Jean-Jacques’s lover, Mademoiselle Prévost, for serially cheating on him with another young man. The current manuscript includes Prévost’s response, which noted that the ambassador failed to pay an agreed-upon annuity of 6000 livres as promised to her while they were lovers. She later won the case in court.

Prévost, Antoine François. Mémoires pour servir à l'histoire de Malte, ou, histoire de la jeunesse du commandeur de ***. Amsterdam: François des Bordes, 1741.

The brutality of a knight of the Order of Saint John of Jerusalem

Antoine François Prévost's fictional autobiography entitled Memoires pour sevir à l’histoire de Malte was written from the point of view of an older knight of the Order of Saint John of Jerusalem as he reflects on stories from his youth in the Order. His tales of battle and his brethren’s actions recall heinous and senseless acts of violence. The critique was damning in the eyes of the public since knights were expected to fight with an air of chivalry. The Memoires, though abhorred by the Order, was incredibly popular with the French public, who found the violence equally enthralling and appalling.

Carlo Carasi. L'Ordre de Malthe dévoilé ou Voyage de Malthe. Paris: 1790.

The scandalous exploits of the Order of Saint John of Jerusalem

Scandalous literature destabilized the privileged status of the nobility and Catholic Church in France during the 18th century contributing to the sentiments of the French Revolution in 1789. The L'Ordre de Malthe dévoilé, attributed to Carlo Carasi, details the scandalous behavior of the knights and chaplains of the Order of Saint John of Jerusalem in Malta and France. The portrayal of the knights as being unworthy of their religious status justified the revolutionaries’ desire to seize their property for the new nation and expel the Order from France.

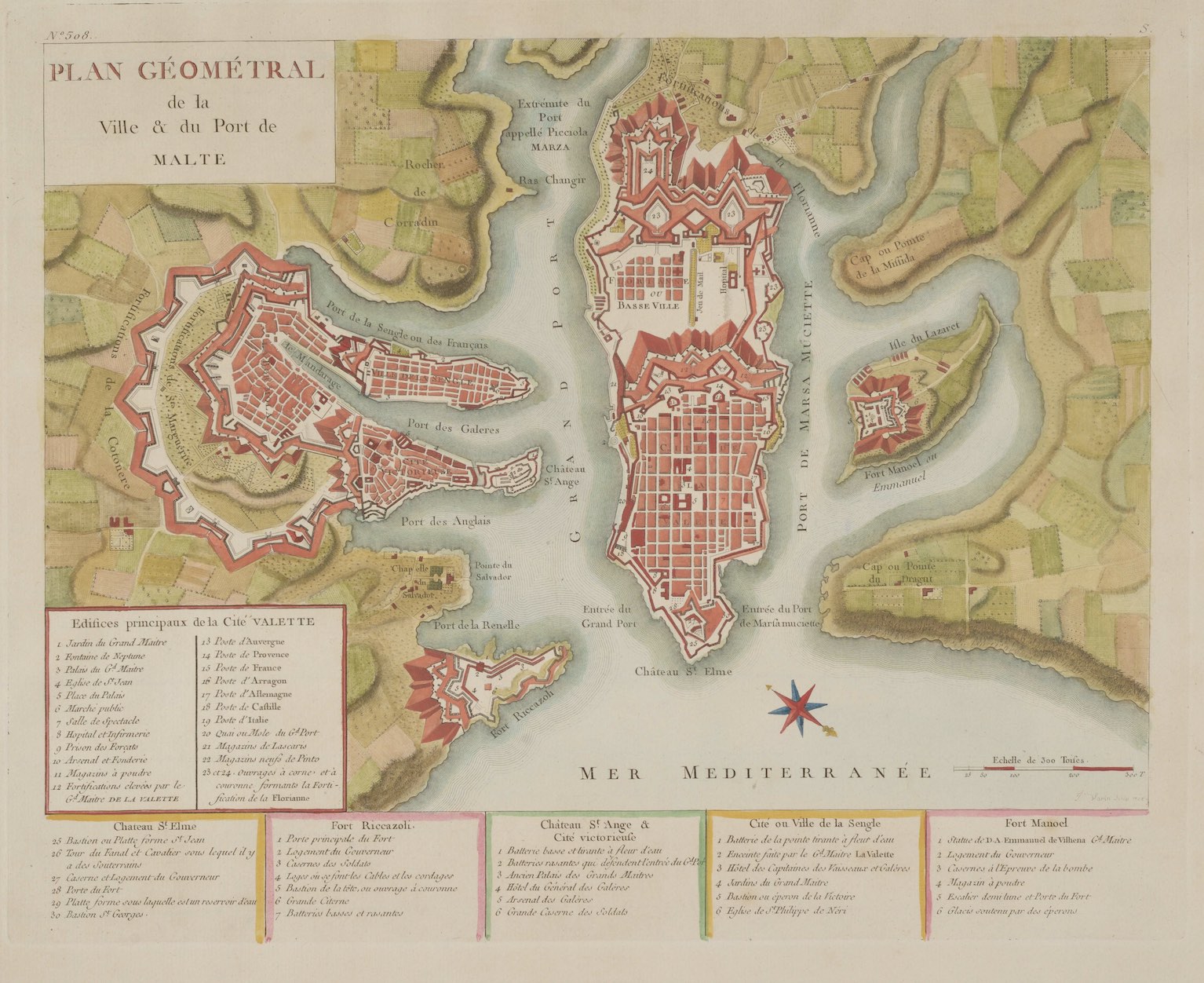

Varin, Joseph. Plan géométral de la ville & du port de Malte. 2nd edition. Paris: 1795.

Plan of the fortifications of Valletta and the port of Malta

Though most commonly found in atlases or nautical cartographic collections, plans of Valletta and its fortifications were also found in histories and travel narratives of the Order of Saint John and the Mediterranean. First printed in Richard de Saint Non’s 1785 edition of the Voyage Pittoresque ou description des royaumes De Naples et De Sicile, Joseph Varin’s map of Valletta provided details about the fortifications of the harbor, which any military commander could use to prepare for a siege and attack on the city.

Assemblée nationale constituante. Lettres patentes du Roi, Saint Cloud, July 31, 1790. Auxerre: Laurent Fournier, 1790.

The Rights of the Order of Saint John in Revolutionary France

The King of France protected the rights and privileges of the Order of Saint John of Jerusalem for centuries. But with the 1789 Revolution, the will of the king bent to the will of the revolutionary National Constituent Assembly. On February 13, 1790, the Republican government suppressed all religious Orders, excluding the Order of Saint John. While the Order survived, it suffered numerous setbacks. In July 1790, the Order still maintained its property, but its income would now be paid directly to the French treasury.

Charles-Joseph Mayer. Considérations politiques et commerciales, sur la nécessité de maintenir l'Ordre de Malte tel qu'il est. Paris: 1790.

Defending the Order of Saint John in Parliament

After the July 1789 Revolution in France, the Order of Saint John of Jerusalem understood that their ability to maintain their position as a legal military religious order was under threat. The Order began an intensive public campaign to defend its role as a protector of French commerce and defender of the French coastline from Barbary pirates and other enemies of Christendom. The Order engaged in secret diplomacy with supporters like Charles-Joseph Mayer, who published pamphlets highlighting the Order’s neutrality and benefits to France.

Loi du 19 septembre 1792, l'an quatrième de la liberté. Ventes des biens de l'Ordre de Malte. Saint-Brieuc, France: J. M. Beauchemin, 1792.

Suppressing the Order of Saint John of Jerusalem in France

The three French langues of the Order of Saint John of Jerusalem came to an end on September 19, 1792, when the Assemblée nationale législative decreed that all properties of the Order would be confiscated by the state. The National Assembly also suppressed all seigneurial rights previously granted to the Order. A pension was decreed to support the Order’s members, and a special annual payment would be paid each year to Malta to support the Order’s fleet and hospital in Valletta, as it benefitted French merchants.

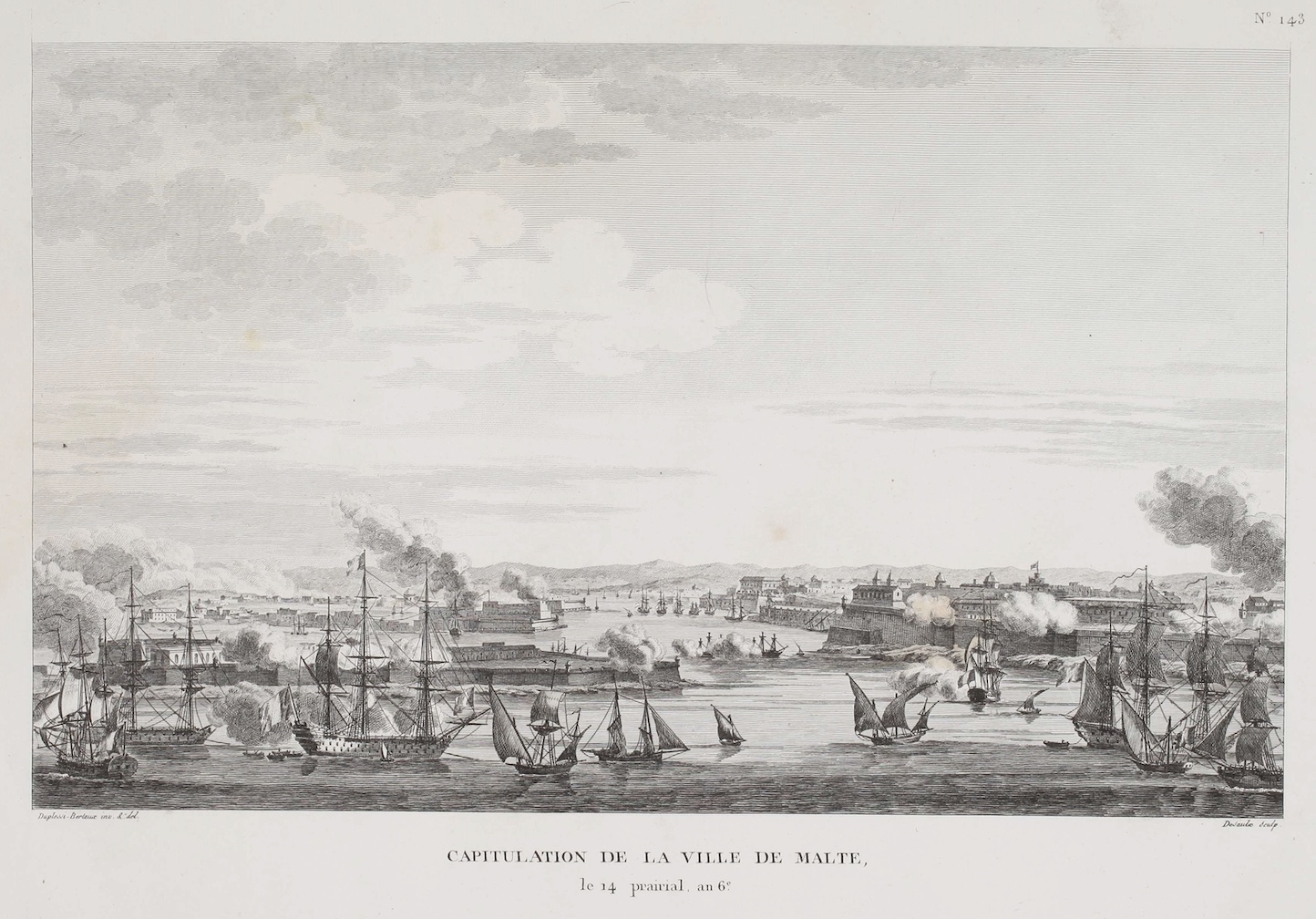

Desaulx, Jean. Capitulation de la Ville de Malte, le 14 prairial an 6.e. Paris: Pierre Didot, 1802-1804.

French Republican fleet bombarding Valletta in June 1798

Napoleon Bonaparte’s invasion of Malta brought the French revolution to the central Mediterranean. The French general desired Malta as a major port and staging point for French forces in his campaign to conquer Egypt and hinder Great Britain’s attempt to control Mediterranean trade from Alexandria to Gibraltar. Bonaparte knew from turncoat knights that Malta could not withstand a prolonged assault. His pretext to use the port to water his ships gave way to a full-scale assault on June 10, 1798.

Louis de Boisgelin. Ancient and Modern Malta. London: Printed for Richard Phillips, 1905.

Bonaparte’s terms of surrender for Malta, June 12, 1798

By June 12, 1798, the Order of Saint John of Jerusalem recognized that it would not prevail against the forces of Napoleon Bonaparte. An embassy was sent to the flagship L’Orient, where the French general dictated terms of surrender. Several French knights were accused of treason. Indeed, Fra Jean Bosredon de Ransijat became the first French president of Republican Malta from 1798-1800. French knights were allowed to return to France and were afforded a pension, but the days of the Order of Saint John had come to an end in Revolutionary France and Malta.

Mandar, Théophile. Chant d'un barde, sur la conqête de l'Isle de Malthe, par les Français. Paris: Imprimerie du Journal des Campagnes et des Armées, 1798.

Bonaparte’s defeat of the invincible Knights of Malta

Napoleon Bonaparte’s conquest of Malta vindicated the destiny of the French revolutionary movement and added a crown jewel to the future emperor’s series of improbable military victories. French Republican propagandists quickly produced materials lauding Bonaparte’s victory. For Théophile Mandar, the ability to defeat the Order of Saint John was magnified by the historic defense of Malta in the Great Siege of 1565, a feat they could not repeat against the French general despite their impregnable fortress city of Valletta.

![Vue de la Prise de l'Isle de Malthe. Paris: Jacques-Simon Chéreau, [1800?]](../../../assets/img/exhibitions/france-and-the-order-of-saint-john-of-jerusalem/4_11_HMML_00626_001.jpg)

Vue de la Prise de l'Isle de Malthe. Paris: Jacques-Simon Chéreau, [1800?]

View of the French Republican capture of Valletta in June 1798

The French assault on Malta and Gozo began on June 10, 1798. Gozo surrendered on the first day of the assault, while the Order of Saint John of Jerusalem and the Maltese held out in Malta. By June 12, Grand Master Ferdinand von Hompesch knew that his forces could not bear the full assault of the French army and navy and began negotiations for surrender. Napoleon landed in Malta on June 13th and received the formal surrender of the Order, whose reign over the island fortress ended after 268 years.

The Order of Saint John of Jerusalem after the Revolution

The suppression of the Order of Saint John in France in 1792 and its expulsion from Malta in 1798 deprived the Order of the largest contingent of its membership and wealthiest properties. After the restoration of the French monarchy, the Order began reconstituting itself in France, while also becoming a historical ideal for young Catholic men. England claimed Malta as a colony, and with that reconstituted the Order in London with the aid of French émigrés.

Marchangy, Louis-Antoine-François de. Mémoire historique pour l’ordre souverain de St.-Jean de Jérusalem. Paris: Adrien Égron, 1816.

History of the Order of Saint John of Jerusalem

French knights attempted to reestablish the Order of Saint John of Jerusalem in France after the fall of the revolutionary government and the establishment of the First French Empire in 1804. Discussions accelerated with the monarchy’s restoration under King Louis XVIII in 1814. Louis-Antoine-François de Marchangy proposed restoring Order to support the conservative bulwarks of the nobility and the Catholic Church while benefiting from its international diplomacy and defense of French maritime commerce.

Vertot, Réne Aubert de. Abregé de l’histoire del chevaliers de Malte. Tours, France: Mame et Cie, 1858.

A children’s edition of the history of the Order of Saint John of Jerusalem

The reign of King Louis Philippe I brought a conservative Catholic revival to France as the monarchy withstood the July Revolution of 1830. The French Church saw the knights of the Order of Saint John of Jerusalem as models for Catholic youth for their chivalry and defense of the faith. The Biblothèque de la Jeunesse Chrétienne published simplified and abridged versions of Vertot’s history for young readers, replete with engravings emphasizing the heroic nature of the knights and their legendary feats of arms, including fighting dragons.

d'Avezac, Marie-Armand-Pascal and Frédéric Lacroix. L'Univers pittoresque. Paris: Firmin Didot, 1848.

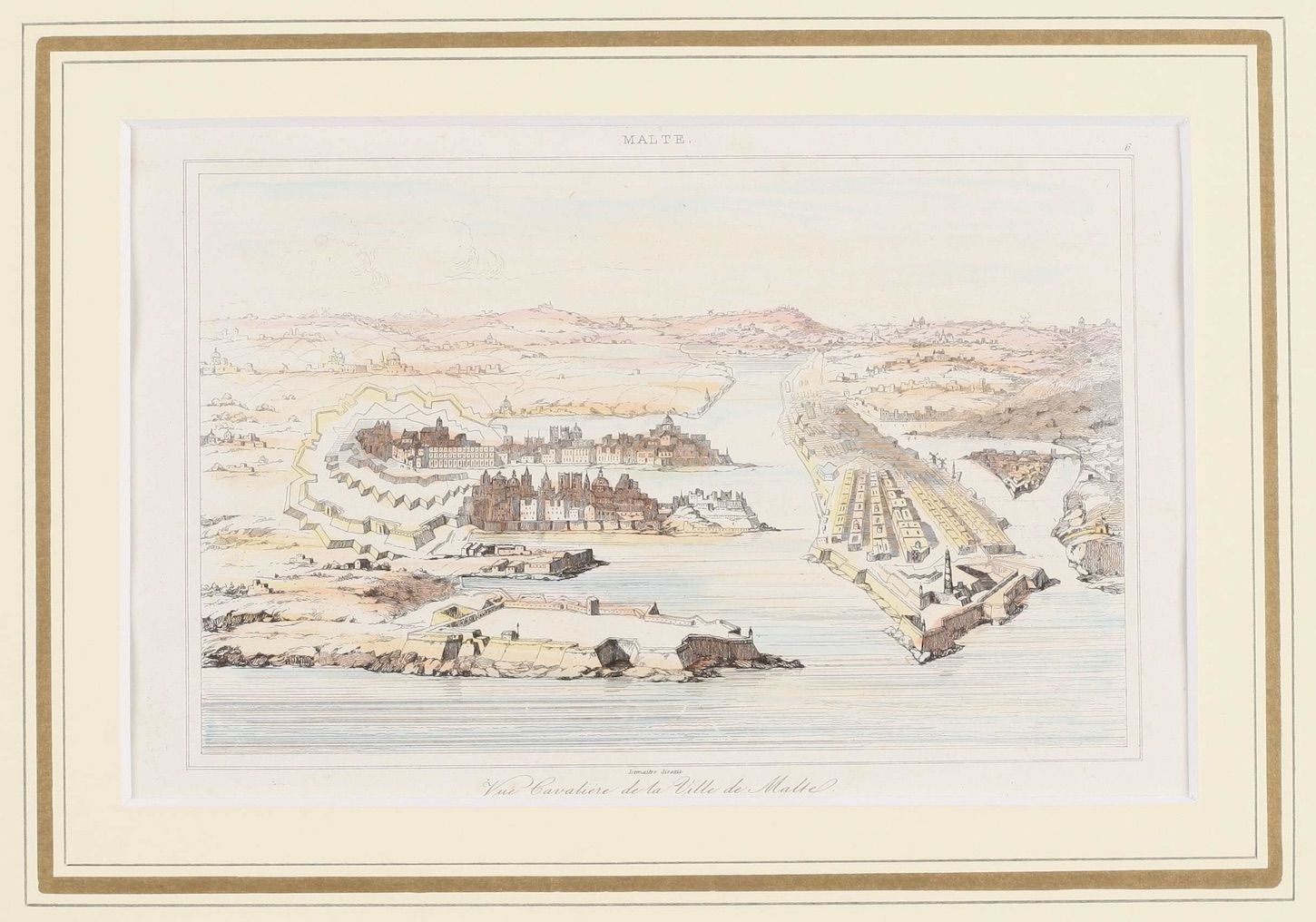

19th-century French view of Malta after British colonization

François Augustine Lemaitre’s Vue Cavalière de la Ville de Malte, printed in the L'Univers pittoresque, offers a bird’s-eye view of Valletta’s fortifications and harbors. The seemingly dramatic view is also empty, void of the fleet of the Order of Saint John and its banners, while any sense of British occupation is absent. Laimatre’s depiction of the Order’s fortified Renaissance city reminds the French reader of the Order’s exile and the disappearance of French knights and influence from the island.

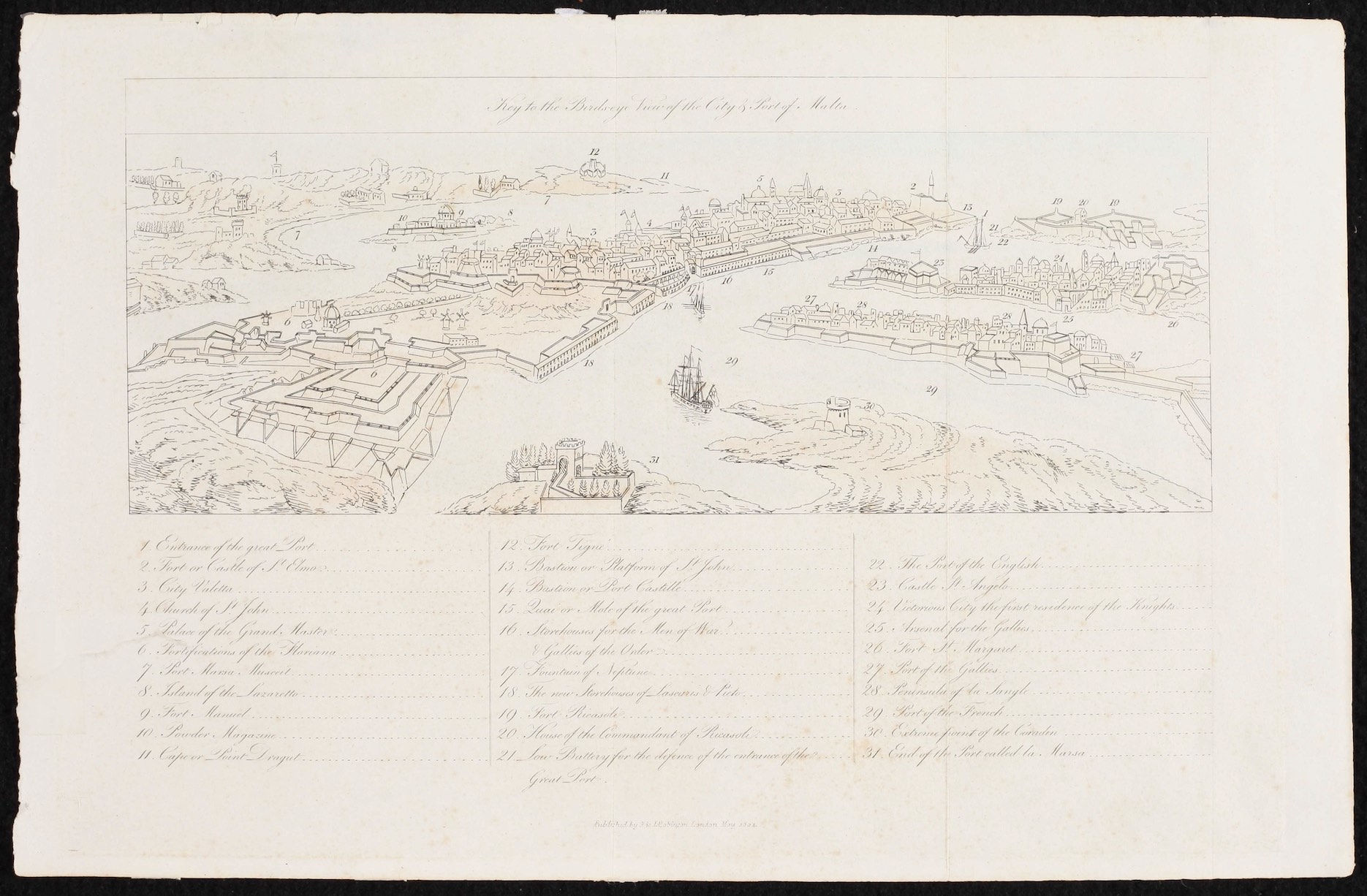

Boisgelin de Kerdu, Pierre Marie de. Key to the birds-eye view of the city & port of Malta. London: George and James Robinson, 1804.

A French knight’s perspective on the British Grand Harbor of Malta

The French surrender to Maltese and British forces in September 1800 left Malta in a state of political ambiguity. The island remained under the sovereignty of the King of Sicily, while the feudal sovereignty of the Order of Saint John of Jerusalem was accepted at the Treaty of Amiens in 1802. Fra Pierre Marie Louis de Boisgelin de Kerdu’s history map of the Grand Harbor understood the irrevocable change, depicting the British mastery of the Great Harbor with its British-flagged ship of the line sailing into the Mediterranean.

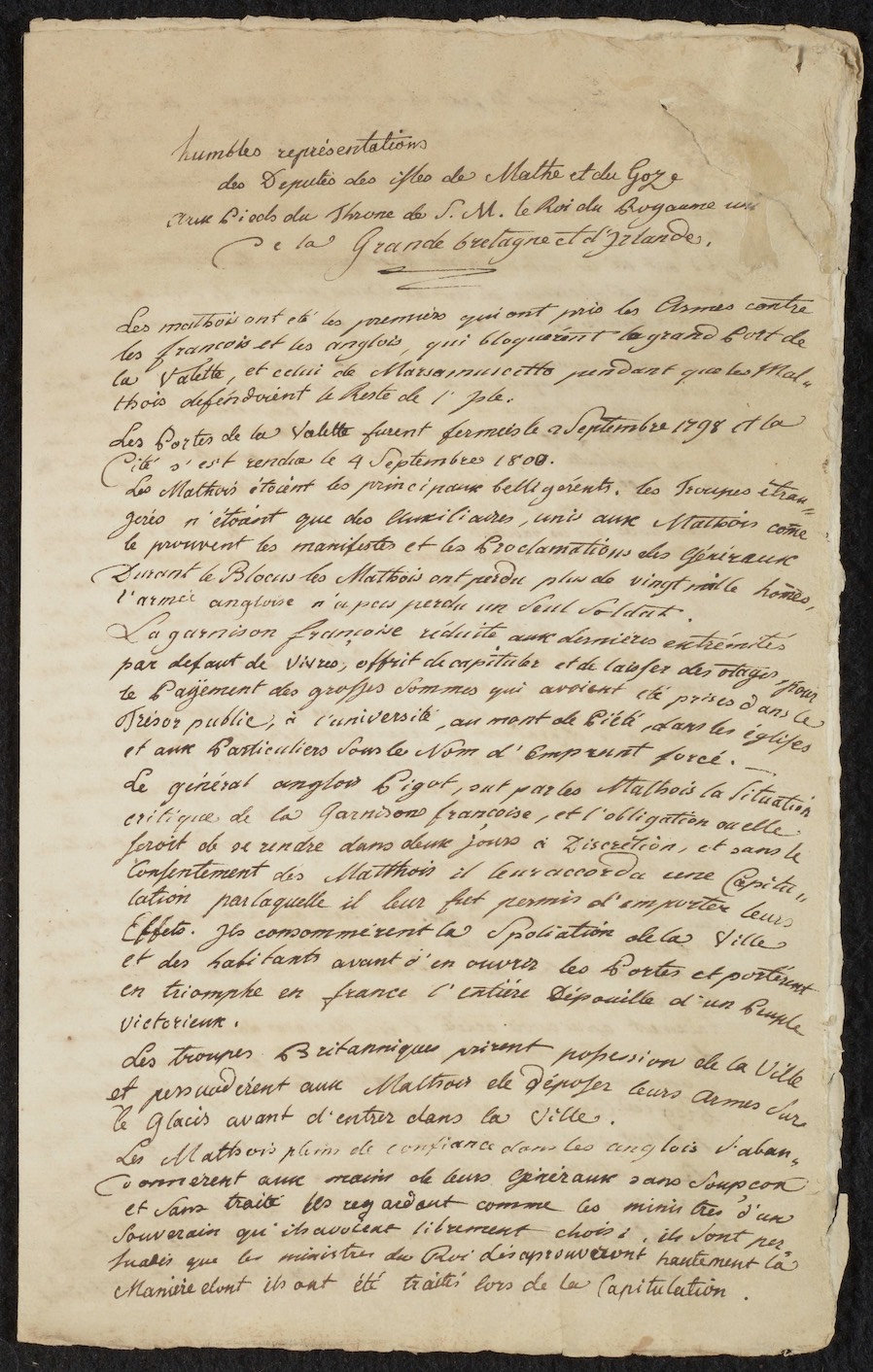

The Humble Representation of the Deputies of Malta & Gozzo, 1801 October 22. France: 1801-1812

Maltese protesting the return of the Order of Saint John of Jerusalem

French translation of a petition written by deputies of the pro-British faction from Malta and Gozo rejecting the idea that the islands be returned to the Order of Saint John of Jerusalem being negotiated at the Treaty of Amiens (1802) after the expulsion of the French from Malta in 1800. Many Maltese rejected the return of the islands to the Order of Saint John, as the Order was dominated by the three French langues, and thus in their opinion, the island would in fact be handed back to France.

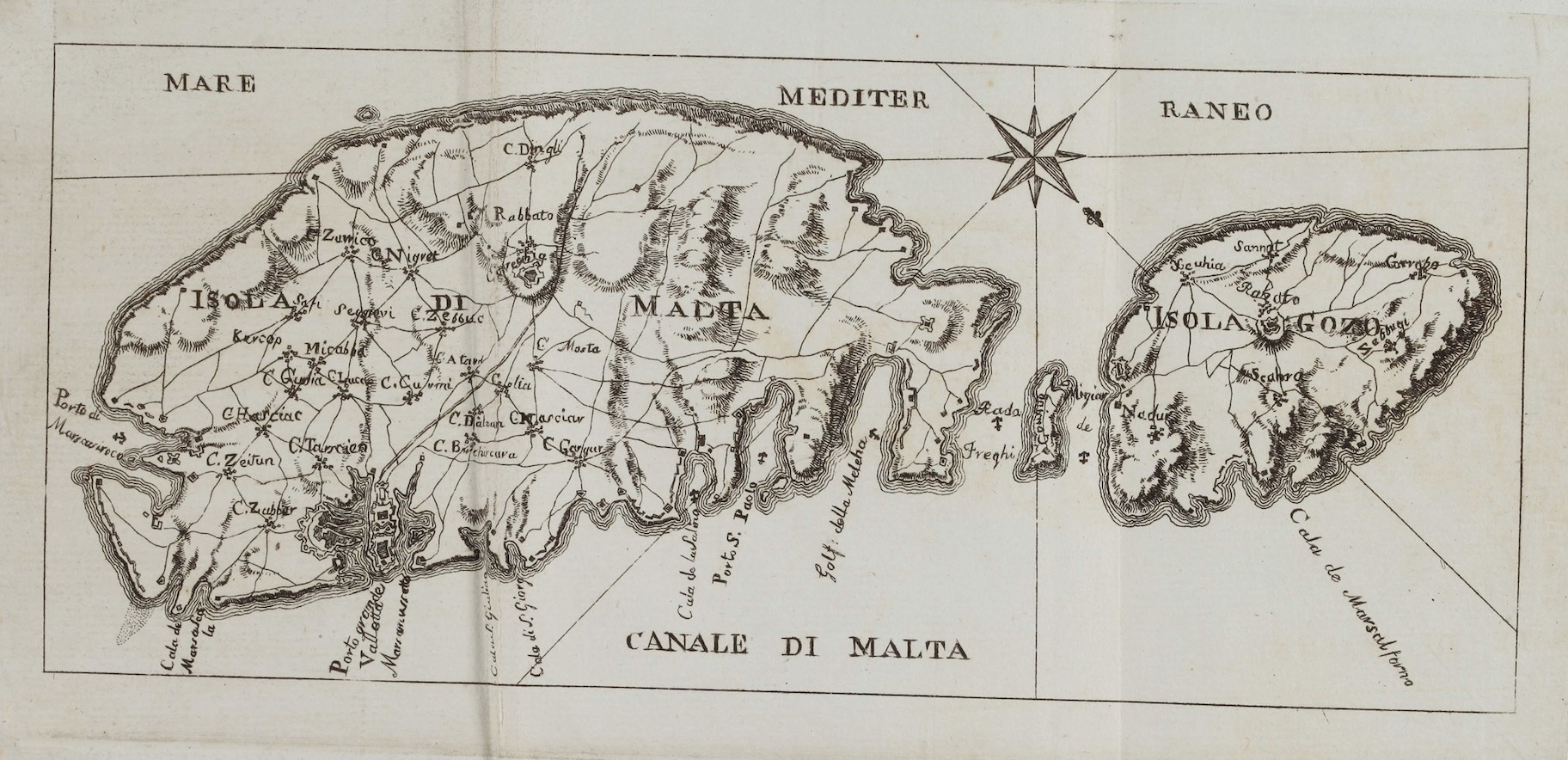

Pericciuoli Borzesi, Giuseppe. The Historical Guide to the Island of Malta and its Dependencies. Malta: the Government Press, 1830.

Malta, a British island and destination for British tourists

Little is known of Giuseppe Pericciuli Borzesi, except that he came from Siena and served as a tutor to Sir Henry Frederick Ponsoby, the son of Frederick Cavendish Ponsonby, Governor of Malta. Pericciuli Borzesi’s guidebook was dedicated to the young Henry and offered a map (in Italian) with a brief introduction to the major sites on the island in English. The era of the knights is treated in the distant past, narrated alongside those of the Phoenicians, Romans, and Angevins despite the recent demise of the Order’s control over the island.

Porter, Whitworth. A History of the Knights of Malta on the Order of the Hospital of St. John of Jerusalem. London: Longman, Brown, Green, Longmans, & Roberts, 1858.

A British history of the of the Order of Saint John of Jerusalem

Whitworth Porter’s History of the Knights of Malta marked a new era in the study of the Order of Saint John of Jerusalem. A major-general in the British Army, Porter’s work followed the military and political history of the Order from its origins to the present day. He viewed Malta’s appanage to the British Crown as of strategic importance, and his history of the Order attempted to introduce the British public to Knights as a historical institution now part of the British Empire. Here the original hospital of the Order in Jerusalem lies in ruins.

![Williams, William Freke. English Battles by Sea and Land. London: London Printing and Publishing Company, [1850-1860].](../../../assets/img/exhibitions/france-and-the-order-of-saint-john-of-jerusalem/5_8_HMML_00293_IMG__001.jpg)

Williams, William Freke. English Battles by Sea and Land. London: London Printing and Publishing Company, [1850-1860].

The British as heirs to the Order of Saint John of Jerusalem

H. Bibby’s bird's eye view of Valletta and the Three Cities encapsulates how the British claimed the island of Malta and the history of the Order of Saint John as its own cultural heritage. The Order’s fortifications and the city of the knights have become a Mediterranean British port, filled with commerce and ships bearing the English merchant ensign. In the margins, a medieval knight of the Order in full plate armor mirrors its modern replacement in the British grenadier with rifle and bearskin cap.

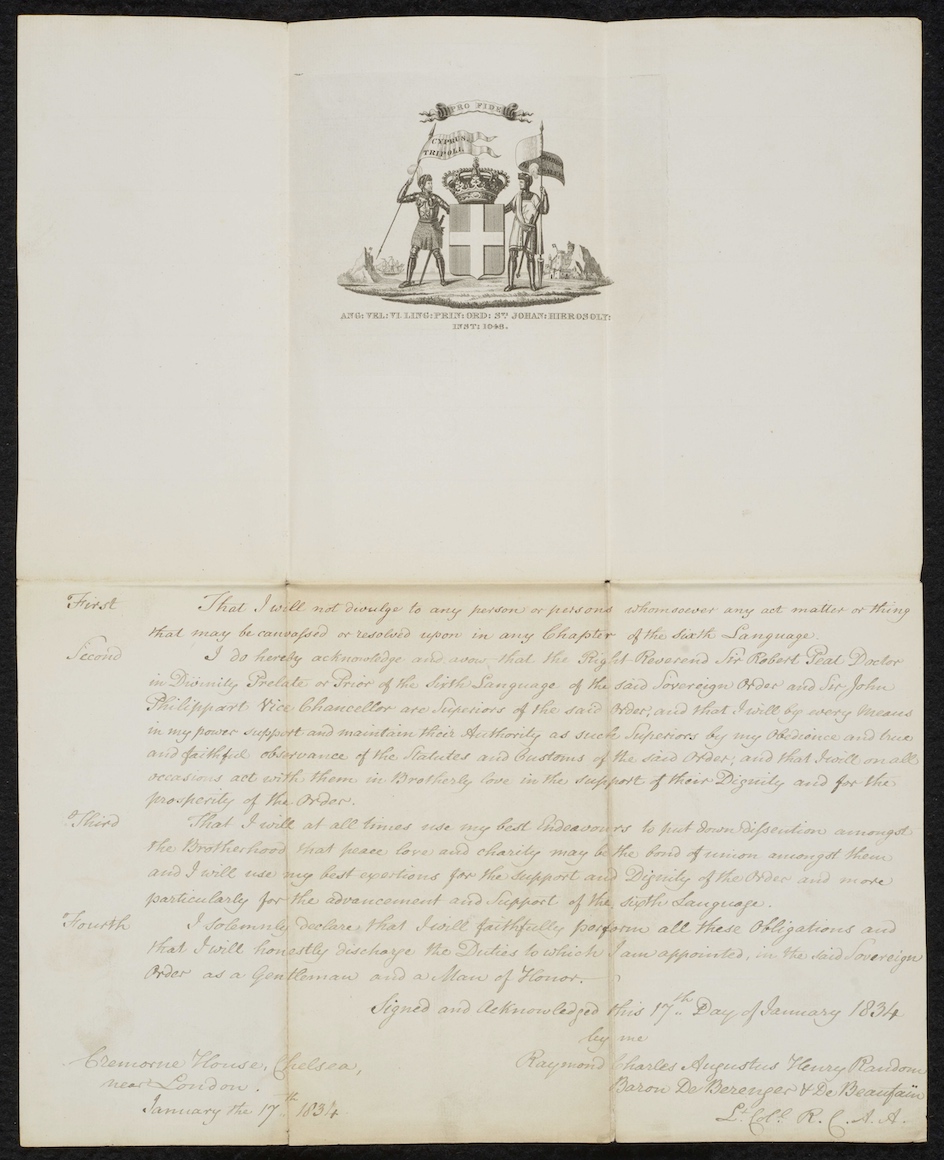

Admission of Raymond Charles Augustus Henry Random, Baron de Bérenguer, to the Venerable Order of Saint John of Jerusalem. Chelsea, England, January 17, 1834.

A new British knight of the Order of Saint John of Jerusalem

In 1831, French Hospitaller émigrés to Great Britain formed a Council of the Langue of England to promote the Order’s revival in Great Britain, where the Order had not existed since its suppression in 1559. The revived English Order became an official Order of Chivalry of the British Crown, chartered by Queen Victoria in 1888. Prior to 1888, English aspirants like Charles Random joined the reconstituted, now Protestant, Order of Saint John to bolster their reputation made possible through the British colonization of Malta.

Curator(s)

Dr. Daniel K. Gullo

Credits

I wish to extend my thanks to Tim Ternes, Mark Spangler, Eamon Cavanaugh, Wayne Torborg, and Mary Hoppe for the installation of the exhibition at HMML and the digital photography supporting the online exhibition. Additionally, I want to extend special thanks to Katherine Blanks, who helped organize the exhibition as part of her summer internship. The exhibition “France and the Order of Saint John of Jerusalem: from Ancient Régime to Revolutionary Europe” was made possible through the generous support of the RMW Foundation and Charles Mifsud, Chair of the Friends of the Malta Study Center.